Angina

Notes

Overview

Angina refers to classic cardiac pain that is felt when there is a reduction in blood supply to the heart.

Angina refers to the central pressing, squeezing, or constricting chest discomfort that is experienced when there is a reduction in blood flow through the coronary arteries. There may be typical radiation to the arm, jaw or neck and it is bought on by physical or emotional exertion and relieved by rest. It typically lasts < 10 minutes.

Angina is the main symptom of myocardial ischaemia, which is usually secondary to coronary artery disease (CAD). However, other conditions can cause angina such as coronary spasm, severe ventricular hypertrophy or severe aortic stenosis.

An estimated 2 million people in England have, or have experienced angina. Patients with angina secondary to CAD are at risk of a major cardiac event:

- Myocardial infarction (MI)

- Cardiac arrest

- Death

Stable vs unstable angina

Stable angina refers to pain that occurs predictably with physical or emotional exertion and lasts no longer than 10 minutes. It should be relived within minutes of rest or with the use of medication (e.g. GTN spray).

Unstable angina refers to a sudden new onset of angina or a significant, and abrupt, deterioration in angina that has been stable. This typically relates to pain that increases with frequency and severity or pain that is experienced at rest. Patients experiencing unstable angina symptoms need urgent admission to hospital for exclusion of acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

See our notes on acute coronary syndrome for more detail.

Aetiology

Angina is most commonly due to coronary artery disease.

CAD refers to the development of atherosclerotic plaques within the coronary vessels, which limits blood flow and precipitates symptoms. There are several risk factors for the development or atherosclerosis (listed below).

On exertion, there is an increased oxygen demand within cardiomyocytes. However, the narrowing of coronary vessels means blood flow cannot be increased to meet this demand. This results in myocardial ischaemia that is experienced as pain.

Risk factors

Modifiable risk factors:

- High cholesterol

- Hypertension

- Smoking

- Diabetes

- Obesity

Non-modifiable risk factors:

- Age

- Family history

- Male sex

- Premature menopause

Other causes

Several other conditions may cause ischaemia through reduced coronary artery blood flow or an increased oxygen supply/demand mismatch.

- Coronary artery spasm (Prinzmetal angina)

- Microvascular angina (diffuse vascular disease within the microvasculature of the coronary circulation)

- Vasculitis (e.g. Kawasaki disease, polyarteritis nodosa)

- Anaemia (oxygen supply/demand mismatch)

- Severe left ventricular hypertrophy (reduced subendocardial blood flow and increased susceptibility to ischaemia)

- Severe aortic stenosis (increases myocardial oxygen demand)

NOTE: historically microvascular angina was termed cardiac syndrome X. Patients develop symptoms of angina with non-obstructive coronary artery disease at angiography due to disease within the small vessels

Chronic coronary syndrome

Chronic coronary syndrome refers to the chronic stable period of coronary artery disease.

CAD is a dynamic process that results from atherosclerotic obstruction of coronary vessels (discussed below). It may present in different ways, which are broadly grouped into two categories:

- Acute coronary syndrome (ACS)

- Chronic coronary syndrome (CCS)

Traditionally, ‘chronic stable angina’ was used to describe patients with symptomatic CAD but without ACS. This has now been replaced with CCS. This is a relatively new term, which refers to six clinical presentations of CAD, which each have a different risk of developing a major cardiac event (e.g. MI, death).

Pathophysiology

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory process which predisposes individuals to angina and ACS.

The development of atherosclerosis is a complex process that involves lipids, macrophages and smooth muscle. Atherosclerosis leads to the formation of an atheroma, which contains a hard plaque on its surface. This plaque is at risk of rupture, which may lead to ACS.

The presence of atherosclerosis within coronary vessels is termed coronary artery disease (CAD) or ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and it may be obstructive (i.e. >50% of the vessel lumen) or non-obstructive (<50% of the vessel lumen).

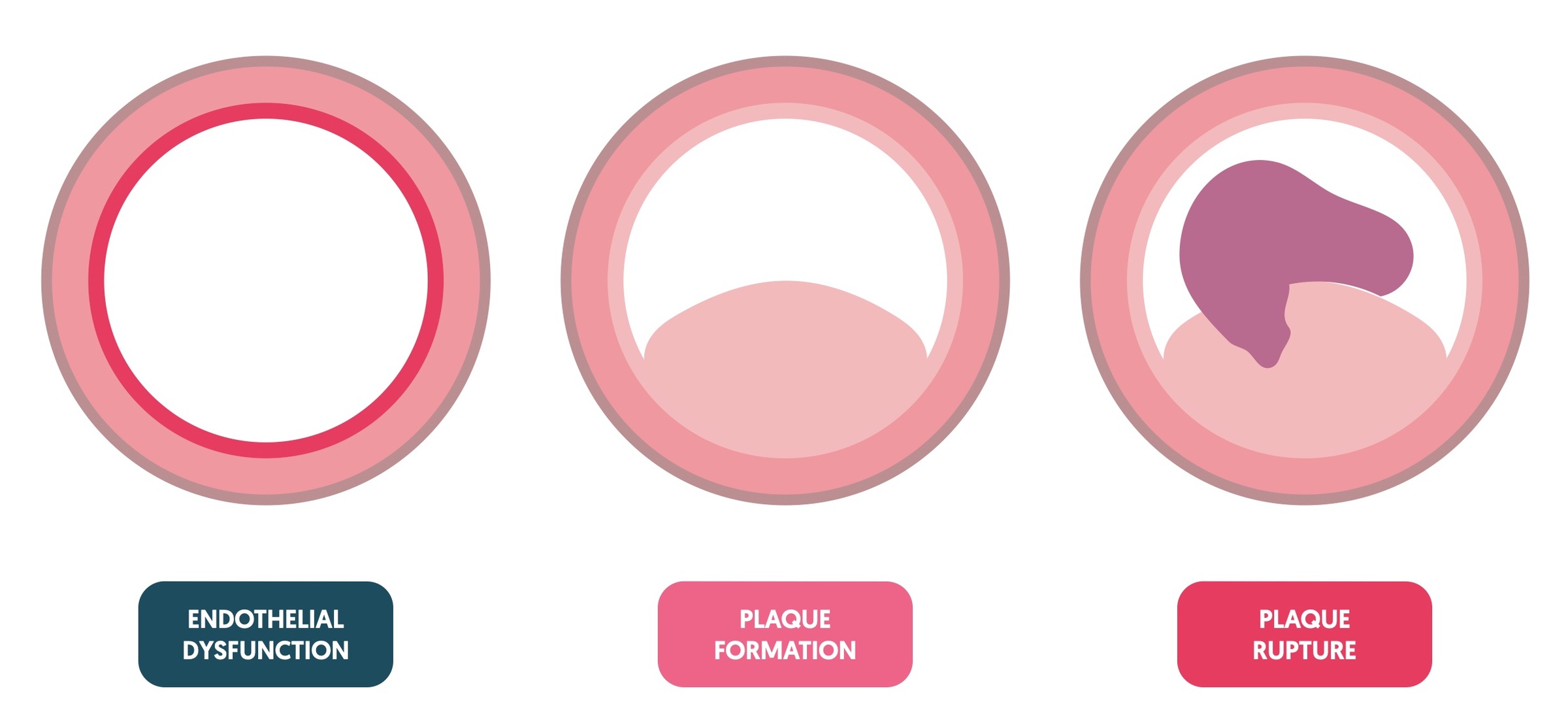

Atherosclerosis develops in three steps: endothelial dysfunction, plaque formation, plaque rupture.

Step 1 - endothelial dysfunction

The first step is endothelial injury. This causes a local inflammatory response. If the injury recurs or healing is incomplete, inflammation may continue leading to the accumulation of low-density lipoproteins (LDL). These become oxidised by local waste products creating reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Step 2 - plaque formation

In response to these irritants, endothelial cells attract monocytes (macrophages). These engulf (phagocytose) the LDLs swelling to become foam cells and ‘fatty streaks’.

Step 3 - plaque rupture

Continued inflammation triggers smooth muscle cell migration. This forms a fibrous cap, which together with the fatty streaks, develops into an atheroma. At this stage, it causes vessel narrowing and may lead to angina.

The top of the atheroma forms a hard plaque. This may rupture through its endothelial lining exposing a collagen-rich cap. Platelets aggregate on this exposed collagen forming a thrombus that may occlude or severely narrow the vessel. Alternatively, the thrombus may break loose, embolising to infarct a distant vessel. This is the pathological mechanism of type I myocardial infarction.

Clinical features

Angina is defined by the presence of typical cardiac chest pain.

The three classic features of angina include:

- Constricting pain experienced in the chest +/- typical radiation to the arm/neck/jaw

- Precipitated by physical exertion

- Relieved by rest or GTN within 5 minutes

Based on these classical features, angina can be differentiated into three types:

- Typical: all three of the above features

- Atypical: two of the above features

- Non-anginal: ≤1 of the above features

Non-anginal chest pain

The following features are more suggestive of non-anginal chest pain, but it is important to consider these in the context of cardiovascular risk factors:

- Continuous or very prolonged pain, and/or

- Unrelated to activity, and/or

- Bought on by breathing, and/or

- Associated with dizziness, palpitations, paraesthesia

Other features

- Dyspnoea: maybe the only presenting feature of CAD in the absence of chest pain. Consider CAD if precipitated by exertion and improved on rest.

- Palpitations: angina may be precipitated by tachyarrhythmias (e.g. atrial fibrillation). These increase the oxygen supply/demand mismatch and reduce the filling time of the coronary vessels during diastole.

- Syncope: may be suggestive of dangerous valvular or cardiac muscle disease causing angina, particularly if it occurs on exertion.

Concerning chest pain

- Chest pain lasts > 10 minutes

- Chest pain not relieved by two doses of GTN taken 5 minutes apart

- Significant worsening/deterioration in angina (e.g. increased frequency, severity or occurring at rest)

The above features may be suggestive of ACS and patients need immediate medical attention.

Grading angina

The severity of angina can be graded according to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society.

- Grade I: angina with strenuous activity (e.g. limitation on strenuous or prolonged ordinary activity).

- Grade II: angina with moderate activity (e.g. slight limitation if normal activities performed rapidly).

- Grade III: angina with mild exertion (e.g. difficulty climbing one flight of stairs at normal pace).

- Grade IV: angina at rest (e.g. no exertion needed to trigger).

Diagnostic work-up

Patients with suspected angina, or recent onset chest pain, need a full work-up.

Both NICE (CG95) and the European Society of Cardiology provide guidelines on the assessment and investigation of patients with suspected angina secondary to CAD.

The diagnostic work-up of angina should aim to:

- Exclude the possibility of ACS: if concern, follow ACS guidelines

- Determine the typicality of angina symptoms and functional ability of the patient

- Undertake basic investigations (e.g. blood tests, ECG, echocardiography +/- chest x-ray)

- Determine the probability of CAD: based on history, examination, and basic investigations

- Offer diagnostic testing where appropriate

- Offer appropriate therapy: this is based on the perceived risk of a major cardiac event (e.g. MI, death)

Rapid access chest pain clinic

In the UK, patients with new-onset exertional chest pain suspected to be angina should have access to a rapid access chest pain clinic (RACPC). These clinics provide patients with early access to specialist cardiology assessment including diagnostic testing. It aims to identify new CAD and prevent a major cardiac event by offering earlier intervention.

In patients with established CAD, who are already known to cardiology services, development of angina should be discussed in cardiology clinic (locality dependent).

Basic investigations

This refers to first-line investigations for determining if patients have evidence of CAD or major risk factors for CAD (e.g diabetes mellitus). They should be completed as an outpatient, usually in a RACPC, unless there is concern about ACS (follow ACS guidelines).

- Blood tests: FBC, U&Es, Lipid profile, blood glucose, HbA1c (TFTs if concern re. thyroid disease)

- Resting ECG: look for indirect signs of CAD (e.g. pathological q waves, conduction abnormalities, ST-T wave changes).

- Echocardiography: essential to assess LV function, valvular pathology and any motion abnormalities (sign of ischaemic disease).

- Chest x-ray: may be needed if atypical symptoms, features of heart failure or suspicion of pulmonary disease.

NOTE: troponin should only be completed if there is concern about unstable symptoms (i.e. acute coronary syndrome)

Pre-test probability of CAD

This refers to the likelihood of CAD based on age, sex and typicality of symptoms. The pre-test probability helps guide what further testing is required, if any, to determine the presence of CAD.

- Pre-test probability >15%: non-invasive functional testing recommended

- Pre-test probability 5-15%: consider further testing based on basic investigations and risk factors.

Offering diagnostic testing

Diagnostic testing can be offered to patients to diagnose or exclude CAD.

- Offer anatomical non-invasive testing (e.g. CT coronary angiography), IF

- Low clinical likelihood of CAD

- No history of CAD

- Offer non-invasive function testing (e.g. stress echocardiography), IF

- High clinical likelihood of CAD

- Revascularisation therapy likely needed

- Established CAD

- Offer invasive coronary angiography, IF

- High clinical likelihood of CAD and symptoms unresponsive to medical therapy

- Typical angina at low activity level and high risk of cardiac event

- LV dysfunction on ECHO suspected secondary to CAD

If the clinical likelihood of CAD is high based on clinical assessment alone, it may be reasonable to only offer further testing if there is a high risk of a major cardiac event.

Anatomical testing

A CT coronary angiography (CTCA) allows visualisation of the coronary artery lumens.

CTCA should be offered to patients deemed to be low risk as a way of excluding CAD. If obstructive CAD is identified, patients require further functional or invasive testing to determine the significance of obstruction.

Obstructive CAD defined as:

- ≥ 70% stenosis of ≥1 major coronary artery segment, OR

- ≥ 50% stenosis in the left main coronary artery

Functional testing

A number of functional non-invasive tests can be offered to patients to look for myocardial ischaemia.

Functional tests are used to diagnose obstructive CAD by the detection of myocardial ischaemia when the heart is put under stress (e.g. using a pharmacological agent or exercise).

They can be offered to patients at high likelihood of CAD when revascularisation is likely. Alternatively, they should be used in patients with established CAD where it is unclear if symptoms are related to myocardial ischaemia.

Examples include:

- Dobutamine stress echocardiography

- Stress or contrast cardiac MRI

- Perfusion changes by single-photon emission CT (SPECT)

These tests have a high accuracy for flow-limiting coronary artery stenosis compared to invasive functional tests at angiography.

Exercise ECG

Exercise ECG is a traditional functional test that involves a patient running on a treadmill and observing for clinical symptoms and ECG changes suggestive of ischaemia (e.g. ST depression). However, this type of functional test is inferior to other non-invasive and anatomical testing. Therefore, the European Society of Cardiology recommend imaging testing instead of exercise ECG

Invasive investigations

Invasive testing with coronary angiography may be used to diagnose and treating obstructive CAD.

As a diagnostic tool, invasive coronary angiography (ICA) can be offered as a first-line investigation in patients with:

- High clinical likelihood of CAD and symptoms unresponsive to medical therapy

- Typical angina at low activity level and high risk of cardiac event

- LV dysfunction on ECHO suspected secondary to CAD

Alternatively, ICA can be offered following non-invasive testing to confirm CAD, to assess lesions between 50-90% stenosis, to assess multi-vessel disease and to provide revascularisation therapy at time of diagnosis.

Risk stratification

Patients should be risk stratified to determine the need for revascularisation therapy.

The aim of risk stratification is to determine which patients would benefit from revascularisation beyond simply controlling symptoms of angina with medication.

Risk

- High risk: >3% annual risk of cardiac mortality

- Low risk: <1% annual risk of cardiac mortality

These definitions may be based on findings during diagnostic testing for CAD or based on risk scores (e.g. Systematic COronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE)).

Lifestyle management

It is critical patients address lifestyle factors to prevent the progression of CAD.

Addressing lifestyle factors decreases the risk of major cardiac event and mortality. Factors to address:

- Diet: high in vegetables, fruit, and wholegrains. Limit saturated fat to <10% of total intake.

- Alcohol: limit alcohol to <100 g/week (12.5 units/week)

- Smoking: smoking cessation

- Exercise: 30-60 minutes of moderate activity. Even irregular exercise beneficial.

- Weight reduction: aim for healthy BMI (18-25 kg/m2)

As part of general lifestyle management it is important that patients co-morbidities are optimised (e.g. hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes mellitus). All patients should be offered 75 mg aspirin, taking into account bleeding risk and co-morbidities. In addition, patients should be prescribed a statin as appropriate.

Pharmacological management

All patients should be offered a short-acting nitrate PRN (e.g. sublingual GTN) to relieve episodes of angina.

PRN therapy

A short-acting nitrate, such as sublingual Glyceryl trinitrate (GTN), should be given to patients to relieve episodes of angina. It works by causing vascular smooth muscle relaxation, which improves coronary blood flow. Major side-effects include headache and dizziness due to low blood pressure. Patients should be advised to spray 1 to 2 doses under the tongue for an attack of angina. If pain has not subsided in 5 minutes they should repeat the dose. If the pain is ongoing after 10 minutes they should call for an ambulance.

First line treatment

Patients should be offered either a beta-blocker or calcium channel blocker as a first-line treatment. These drugs work by decreasing oxygen demand of the heart muscle. If symptoms are ongoing despite maximal dose the agents can be used in combination. Amlodipine is commonly used, which is a dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker.

Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, such as verapamil or diltiazem, are contraindicated with beta-blockers due to the risk of atrioventricular block (i.e. heart block). Occasionally they may be used in angina treatment as monotherapy. They should be avoided in heart failure.

Second line treatment

If patients cannot tolerate beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers, then monotherapy with one of the following medications may be offered:

- Long-acting nitrate (e.g. isosorbide mononitrate): relaxation of vascular smooth muscle and increases coronary blood flow

- Ivabradine: lowers heart rate through inhibition of cardiac ‘funny channels’

- Nicorandil: potassium channel agonist, which inhibits voltage-gated calcium channels leading to muscle relaxation

- Ranolazine: inhibition of late inward sodium channel, which reduces calcium overload in cardiomyocytes.

Different combinations of these second-line options may be given alongside beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers. This is if patients have ongoing symptoms despite maximal medical therapy. Choice depends on heart rate, LV function and blood pressure.

Invasive management

Revascularisation therapy is an option in patients who are high risk of a major cardiac event or refractory to medical therapy.

Revascularisation therapy should be offered in combination with pharmacological therapy to help prevent serious adverse events and improve symptoms.

Revascularisation (PCI)

Coronary angiography with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) involves insertion of a stent into a coronary artery to improve blood flow and therefore symptoms. PCI may be offered to coronary arteries with significant stenosis or where the flow across a diseased artery, as measured by the fractional flow reserve (FFR), is significantly limited.

Following a stent insertion for ‘stable’ angina, dual anti-platelet therapy should be offered for a minimum of 6 months (e.g. aspirin and clopidogrel). Patients at higher risk may be considered for long therapy.

Revascularisation (CABG)

Coronary artery bypass grafting is a cardiothoracic surgical procedure that aims to restore flow within a coronary vessel through bypass of the obstructed segment. This usually involves using vein grafts or redirecting flow from the internal mammary artery.

Example indications for CABG include:

- >50% stenosis of the left main stem

- >70% stenosis of proximal left anterior descending and circumflex arteries

- Triple-vessel disease (asymptomatic or symptomatic)

- Triple-vessel disease with proximal LAD stenosis and poor LV function

Patients who may qualify for a CABG should be discussed in the joint cardiology/cardiothoracic (JCC) meeting. Decision between PCI or CABG depends on fitness for surgery, coronary anatomy, vessel involvement and patient choice.

Last updated: March 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback