Infective endocarditis

Notes

Overview

Infective endocarditis refers to any infection of the endocardial surface of the heart.

Infective endocarditis (IE) can be a life-threatening condition associated with a number of severe complications. It refers to infection of the inner lining of the heart known as the endocardium. Infection of the endocardium may involve one or more heart valves or an intracardiac device (e.g. prosthetic valve).

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation of IE is highly variable. There are two major disease courses:

- Acute, rapidly progressive infection

- Subacute, or chronic, low-grade infection

IE types

There are three major types, or categories, of IE:

- Native valve endocarditis (NVE): normal valves without previous intervention. May be acute or subacute.

- Prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE): may occur early (< 1 year) or late (> 1 year) following surgical intervention. Account for 10-20% of cases.

- Intravenous drug abuse (IVDA) endocarditis: classically affects the tricuspid valve (50%). Staphylococcus aureus most common microorganism.

Epidemiology

Globally, IE is becoming increasingly common, associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Traditionally, IE was considered a fatal condition, which commonly occurred in patients with pre-existing valvular disease from rheumatic heart disease. In the modern era, use of antibiotics has significantly improved outcomes.

Within the UK, the precise incidence of IE is difficult to quantify. This is because of differences in incidence of underlying cardiac disease (e.g. rheumatic fever), intravenous drug use and use of indwelling cardiac devices (e.g. pacemakers, heart valves).

It is estimated that over 50% of IE cases occur in patients aged > 60 years old. With the increasing number of invasive procedures and use of intracardiac devices, the incidence of IE is expected to rise. The use of devices has led to an increase in Staphylococcal IE, which is now the most common cause.

Risk factors

There are many risk factors associated with the develop of IE, particularly underlying cardiac disease.

Patient-associated risk factors

- Age: more than half of IE cases occur in patients aged > 60 years old.

- Male: sex predominance varies from 3:2 to 9:1.

- Intravenous drug use: may occur due to contamination of drugs used for injection or seeding of skin flora during injection

- Dentition: poor dental hygiene, dental infections and certain dental procedures increase risk.

Cardiac risk factors

- Structural heart disease

- Valvular heart disease: any valve pathology can predispose too IE.

- Congenital heart disease (e.g. bicuspid aortic valve, ventricular septal defect and cyanotic heart disease).

- Prosthetic heart valves: metallic, tissue and transcatheter devices all associated with IE

- Previous IE: recurrence rate 2.5-9% across reports

- Intravascular devices

Other risk factors

- Immunosuppression (e.g. HIV)

- Haemodialysis

Aetiology

Streptococcal and staphylococcal species are implicated in the majority of IE cases.

IE is mainly caused by bacterial infections that enter the bloodstream and then deposit on the endocardial surface of the heart.

The most common cause of IE overall is Staphylococcal aureus, which is the usual pathogen in IE associated with intravenous drug use (IVDU) and prosthetic heart valves. Other commonly isolated bacteria are Streptococcal and Enterococcal species, which used to be the most common cause of IE. They are typically associated with subacute IE.

Causes of endocarditis can be divided into:

- Native valve endocarditis (NVE)

- Prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE)

- IVDU-associated endocarditis

- Culture-negative endocarditis

- Non-infective endocarditis

Native valve endocarditis

NVE is commonly due to underlying rheumatic heart disease, congenital heart disease or structural heart disease. It is usually due to Streptococcal species and presents with a subacute course.

- Streptococcal species (alpha-haemolytic, S. bovis) and enterococci: implicated in around 70% of cases.

- Staphylococcal species: implicated in around 25% of cases. More aggressive disease course.

Prosthetic valve endocarditis

The aetiology of PVE depends on if it occurs early (< 1 year) or late (> 1 year). The time differentiation is an arbitrary cut-off. Some guidelines quote within 60 days as ‘early IE’. Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus (CoNS) account for 30% of PVE (most common).

- Early PVE: occurring shortly after surgery. Staphylococcal species commonly implicated. Acute course that can cause local abscess, fistula formation, and valvular dehiscence.

- Late PVE: occurring a medium-to-long period after surgery. Streptococcal species commonly implicated. Has a more subacute course.

IVDU-associated IE

Due to injection through the venous system, IE affecting the right side of the heart is commonly seen with IVDU. Most common organism implicated is Staphylococcus aureus.

Culture-negative IE

Defined as endocarditis with no definite microbiological aetiology despite adequate sampling. Culture negative IE may be due to:

- Typical pathogens: usual bacterial pathogens may not be cultured in the lab because of early antibiotic use.

- Pathogens with complex growth: some organisms are described as fastidious, with complex growth requirements in the lab

- Intracellular bacteria: these bacteria cannot be cultured by standard methods

- Non-bacterial pathogens (e.g. fungi)

Non-infective endocarditis

Rarely, endocarditis may occur in the absence of infection. Other terms for non-infective endocarditis include marantic endocarditis or Libman-Sacks endocarditis. It is due to sterile platelet thrombi on heart valves.

Causes include:

- Advanced malignancy (80%)

- Systemic lupus erythematous

- Other: Rheumatoid arthritis, burns

Microorganisms

A variety of pathogens can cause IE.

The most common microorganisms that cause IE are Staphylococcal, Streptococcal and Enterococcal species. As discussed, the microorganisms implicated in IE depends on the underlying cardiac disease (e.g. prosthetic or native valve) and patient factors (e.g. intravenous drug use).

Staphylococcal species

- Staphylococcus aureus: causes both acute and subacute IE. May lead to significant valve destruction.

- Coagulase negative staphylococcus (CoNS): subacute course. Commonly associated with prosthetic devices.

Streptococcal species

- Alpha-haemolytic streptococci: commonly implicated in subacute IE due to poor dentition. Accounts for 50-60% of subacute IE cases. Examples include Viridans streptococci.

- Beta-haemolytic streptococci

- Group A: more virulent course, similar to S. Aureus.

- Group B: usually an acute course. Typically seen in pregnancy.

- Group D: streptococcus gallolyticus (previously streptococcus bovis) is a classic cause of subacute IE. It has a strong association with colorectal cancer, which needs to be investigated if isolated.

- Others: group C, G.

Enterococcus

Traditionally, enterococcal microorganisms were classified as beta-haemolytic group D streptococci. However, they have now been reclassified to an independent genus.

- Enterococcus faecalis: most commonly implicated enterococcus.

HACEK organisms

Account for 5% of subacute IE

- Haemophilus aphrophilus

- Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans

- Cardiobacterium hominis

- Eikenella corrodens

- Kingella kingae

Fungal

Associated with a poor prognosis (~50% mortality)

- Candida species (e.g. C. albicans, C. stellatoidea)

- Aspergillus species

Pathophysiology

IE is characterised by the formation of vegetations on cardiac valves.

IE occurs when bacteria enter the bloodstream and deposit onto the endocardial surface of the heart. Classically, a dental procedure is associated with a brief bacteraemia that our immune system is able to control. However, in patients with underlying cardiac disease (e.g. rheumatic heart disease) it can lead to deposition and adherence of bacteria.

Once deposited on the endocardial surface, the organisms adhere and eventually lead to invasion and destruction of the valve leaflets. The key pathological process in IE is formation of infected vegetations.

Natural history

On the endocardial surface, a small nidus of adherent platelet-fibrin complex becomes infected by deposited bacteria. This complex forms a vegetation, which is essentially a collection of fibrin, platelets, white blood cells, red blood cell debris and clusters of bacteria. The vegetation may increase in size and damage the endocardial tissue including valves.

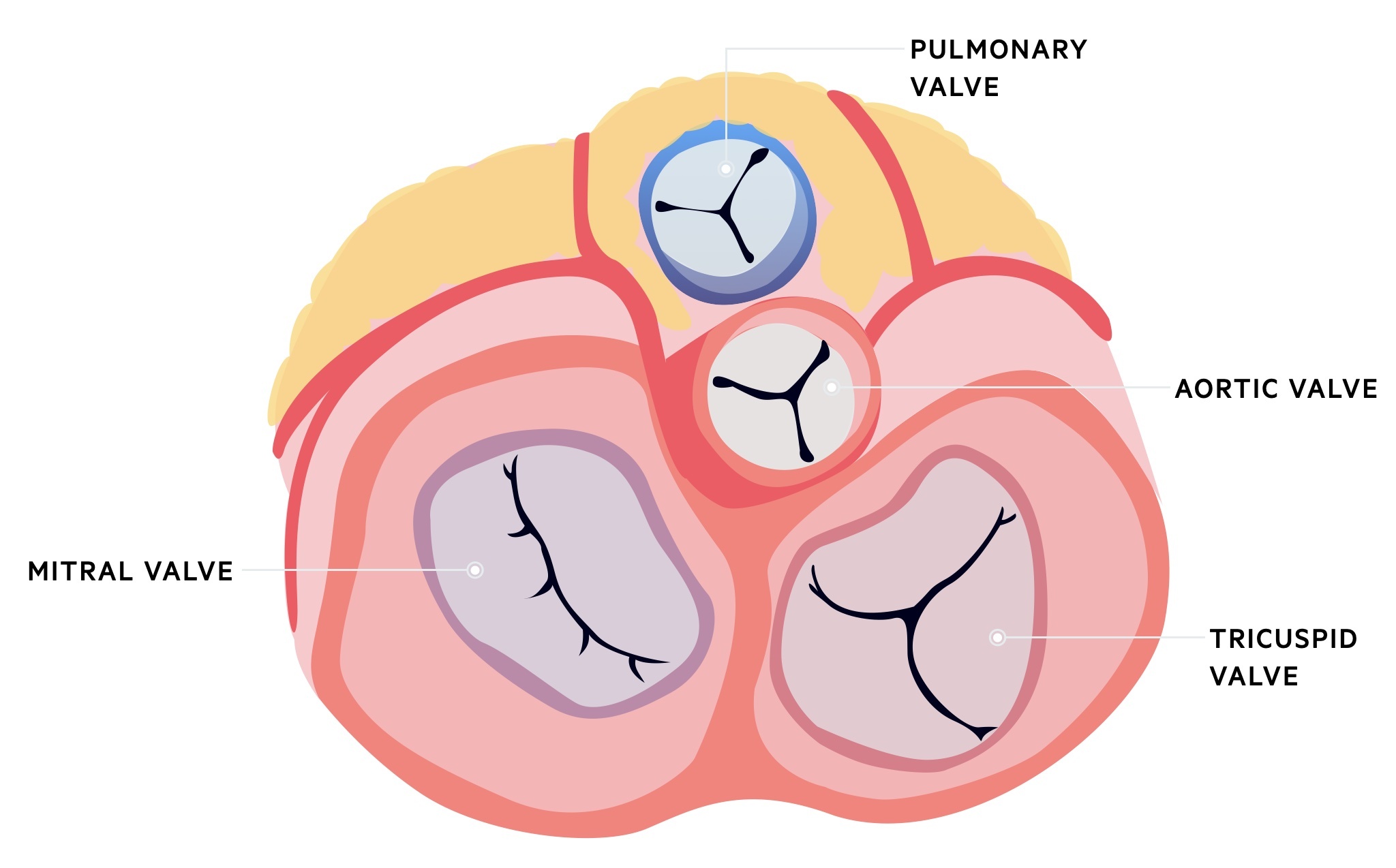

The vegetation can cause local destruction of valves, which leads to regurgitant murmurs and eventually congestive cardiac failure. If this process occurs acutely (e.g. acute IE secondary to Staphylococcal aureus) it can lead to acute heart failure and cardiogenic shock. The order of frequency in which the valves are affected include:

- Mitral

- Aortic

- Combined mitral and aortic

- Tricuspid

- Pulmonary

As well as local cardiac damage, embolic events can occur due to vegetations breaking off and being deposited in other organ systems. The embolisation of fragments of vegetations can lead to the formation of abscesses (e.g. cerebral abscess in left sided endocarditis or pulmonary abscesses in right-sided endocarditis). Alternatively, activation of the immune system and clustering of immune complexes within vegetations can lead to immune-mediated vasculitis within distant vessels following embolisation (e.g. glomerulonephritis).

Clinical features

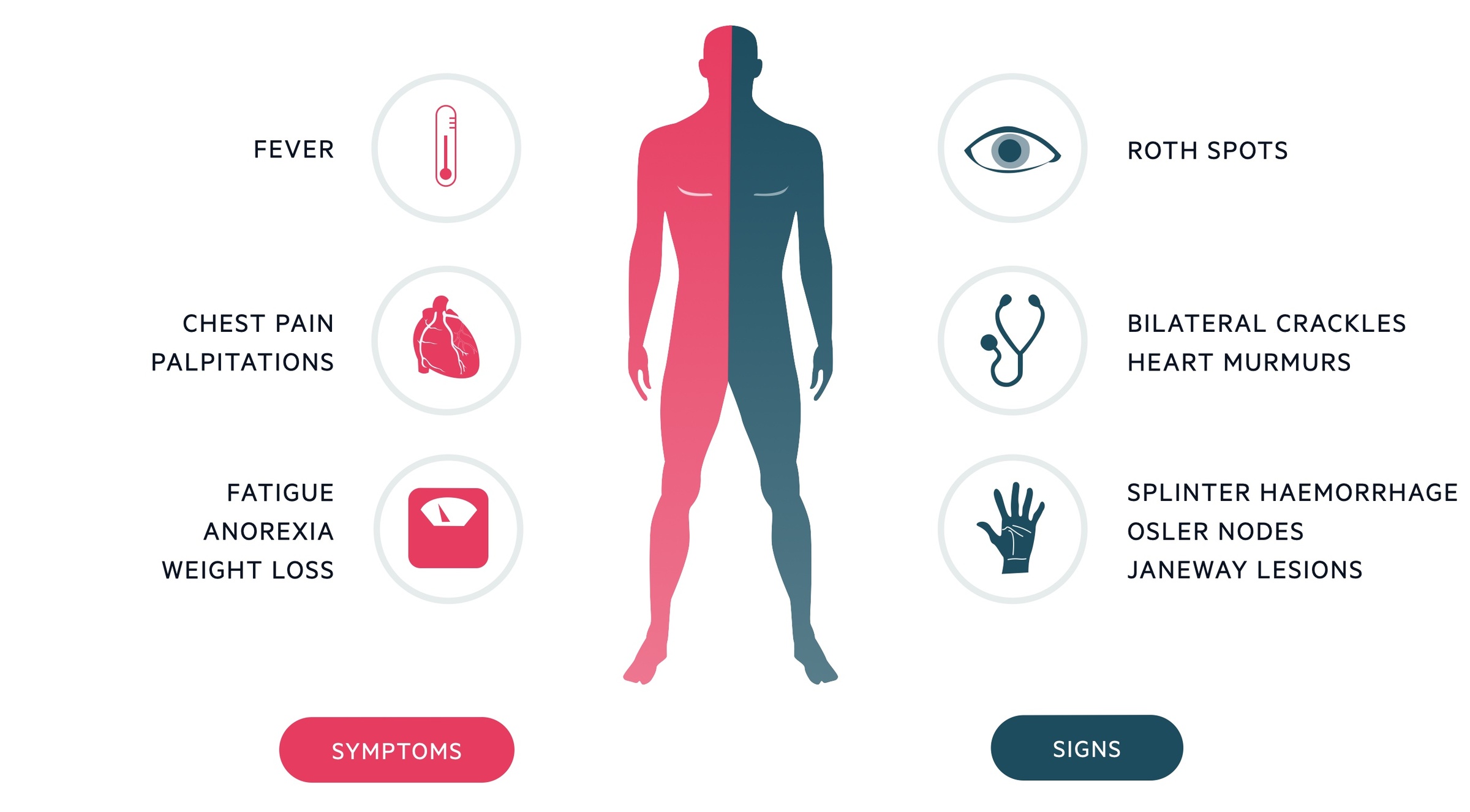

IE is most commonly associated with fever (~90%) and cardiac murmurs (~85%).

The clinical presentation of IE is highly variable depending on the speed of development (acute vs subacute), underlying organism (e.g. Streptococcal vs Staphylococcal) and patients co-morbidities.

In general, acute IE is associated with a rapidly progressive infection that can cause significant cardiac damage, valvular insufficiency and heart failure with or without embolic phenomenon. Subacute IE causes a more prolonged course with low-grade fevers and non-specific symptoms with our without embolic phenomenon.

Symptoms

- Fever (90%)

- Malaise, lethargy

- Anorexia

- Weight loss

- Abdominal pain: splenic abscess

- Haematuria: renal embolic phenomenon

- Cardiac symptoms: shortness of breath, chest pain, palpitations

Signs

- Cardiac murmur (85%): pansystolic murmur of mitral regurgitation or early diastolic murmur of aortic regurgitation classical

- Features of heart failure*: raised JVP, bilateral crackles on respiratory auscultation

- Splinter haemorrhages: thin, red to reddish-brown lines of blood under the nails (microemboli)

- Petechiae (20-40%): skin and mucous membranes (microemboli and immune complex deposition)

- Janeway lesions: nontender erythematous macules on the palms and soles (microabscesses). Acute > subacute.

- Osler nodes: tender subcutaneous violaceous nodules mostly on the pads of the fingers and toes (immune complex deposition). Subacute > acute.

- Roth spots: exudative, oedematous hemorrhagic lesions of the retina with pale centre (immune complex deposition). Subacute > acute.

- Splenomegaly: splenic abscess formation

*NOTE: cardiac complications (e.g. valvular insufficiency, heart failure) seen in up to 50% of cases.

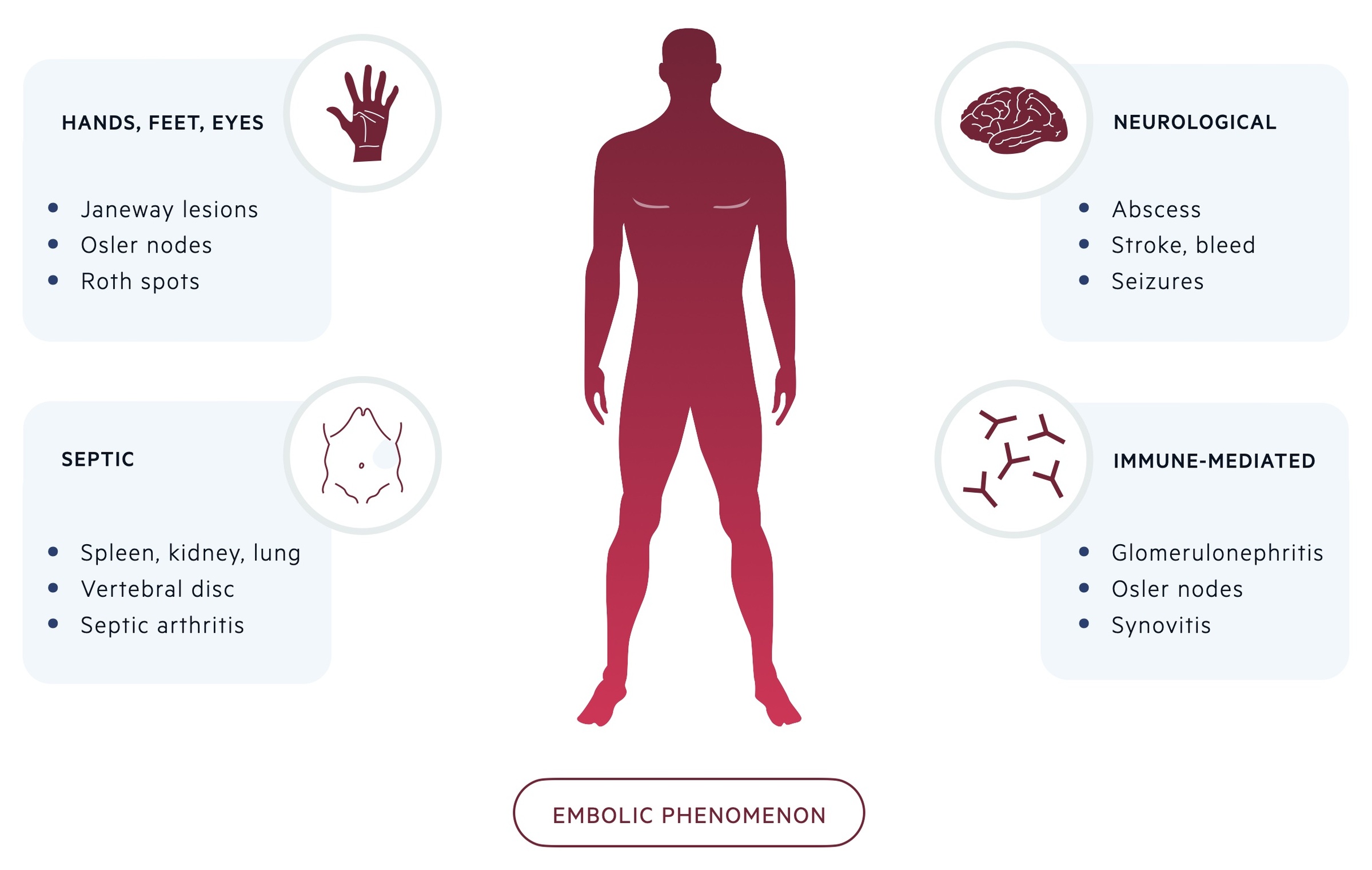

Embolic phenomenon

Around 25% of patients with IE have evidence of embolic phenomenon at the time of diagnosis. Peripheral stigmata of IE are increasingly less common due to earlier recognition and diagnosis.

- Hands and feet: Osler nodes and Janeway lesions (see above)

- Ophthalmological (2%): Roth spots (see above)

- Neurological (40%): cerebral abscess, intracerebral haemorrhage, embolic stroke, seizures

- Septic emboli (25%): splenic, renal, pulmonary abscesses. Vertebral osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, psoas abscess

- Immune reaction (i.e. immune complex deposition): glomerulonephritis, synovitis

Diagnosis & investigations

Echocardiography and blood cultures form the key investigations in the diagnosis of IE.

Microbiology

Positive microbiology with multiple sets of blood cultures is critical in the diagnosis of IE. In any patient with suspected IE, at least 3 sets of blood cultures should be taken at 30 minute intervals with a good volume of blood per bottle (10 mls). Peripheral cultures should be taken with strict aseptic technique. Ideally, blood cultures should be taken before initiation of systemic antibiotics.

NOTE: pathological examination of resected valvular tissue or embolic fragments remains the diagnostic gold standard.

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) or transoesophgeal echocardiography (TOE) are the imaging modalities of choice in suspected endocarditis. TTE is a useful initial investigation that is non-invasive. If the TTE is negative or of suboptimal quality, and the index of suspicion is high, then a TOE is performed. In addition, a TOE is performed following a positive TTE to look for local complications (e.g. valve perforation, abscess formation).

The sensitivity and specificity of TTE for the diagnosis IE is 70% and ~90%, respectively. For TOE, it is 96% and ~90%, respectively.

Findings on TTE/TOE suggestive of IE include:

- Vegetation

- Abscess formation

- Pseudoaneurysm

- Valve perforation

- New dehiscence of a prosthetic valve

Other imaging modalities

Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and nuclear imaging (e.g. CT-PET) are increasingly being used in the diagnosis of IE, particularly for equivocal cases.

Other investigations

- Bedside: urine dip (haematuria/proteinuria)

- ECG: at risk of conduction abnormalities. A prolonged PR interval is suggestive of para-aortic abscess

- Bloods: FBC, U&E, CRP/ESR, LFT, Venous blood gas

- Thorax and abdominal imaging: CT or US may be needed to look for pulmonary or splenic abscesses

- Cerebral imaging: CT or MRI may be needed to assess for neurological complications (even in absence of clinical features)

Modified Duke criteria

In 2000, the modified Duke criteria were recommended for the diagnosis of IE.

The Modified Duke criteria contains both major and minor criteria that are used to make a diagnosis of IE. We detail a simplified version of the Modified Duke criteria below.

Major criteria

- Microbiological criteria: typical microorganisms from two separate blood cultures, OR microorganisms consistent with IE from persistently positive blood cultures (i.e. ≥2 positive cultures from samples ≥12 hours apart, OR, 3 or a majority of ≥4 separate samples taken at least an hour apart).

- Evidence of endocardial involvement: echocardiographic evidence of IE (vegetation, abscess, new dehiscence of a prosthetic valve), OR new valvular regurgitation.

Minor criteria

- Predisposing heart condition or IVDU

- Fever (>38º)

- Vascular phenomenon (diagnosed clinically or by imaging): arterial emboli, infectious aneurysm, intracranial haemorrhage, Janeway lesion, conjunctival haemorrhage.

- Immunological phenomenon: glomerulonephritis, Osler nodes, Roth spots, rheumatoid factor positive

- Microbiological evidence: positive cultures not meeting major criteria. Serological evidence of active infection with organism consistent with IE.

Definitions

Based on the criteria, IE can be divided into definitive, possible and rejected:

- Definite (pathological): vegetation or intracardiac abscess demonstrating active endocarditis on histology, OR microorganism demonstrated by culture or histology of a vegetation or intracardiac abscess

- Definite (clinical): 2 major criteria, OR 1 major and 3 minor criteria, OR 5 minor criteria.

- Possible: 1 major and 1 minor criteria, OR 3 minor criteria

- Rejected: firm alternative diagnosis, OR resolution of symptoms suggesting IE within 4 days of antibiotics, OR no pathological evidence of IE at surgery or autopsy within 4 days of antibiotics, OR does not meet criteria for possible IE.

NOTE: the modified Duke criteria has a lower diagnostic accuracy for prosthetic valve endocarditis and right-sided IE.

Diagnostic algorithm

The diagnosis of IE should follow the European Society of Cardiology diagnostic algorithm.

The European Society of Cardiology produced a diagnostic algorithm in 2015, which incorporates the traditional modified Duke criteria.

The major difference to the modified Duke criteria is the inclusion, and expansion, of using imaging to support the diagnosis of IE. This is particularly important for equivocal cases (possible/rejected) where there is still a high suspicion of IE. New imaging modalities (MRI, CT, CT-PET) can be used to help diagnose embolic events (e.g. cerebral MRI) or assess cardiac involvement (e.g. CT-PET in prosthetic valves) where TTE/TOE findings are negative or inconclusive.

Management

A prolonged course of targeted antibiotics and early involvement of the IE team are essential.

Prolonged use of antibiotics form the cornerstone of treatment of IE. Antibiotics should always be targeted to the organism that has been cultured with reference to the resistance patterns. This should always be completed in close communication with the endocarditis team (discussed below) or microbiology.

Here, we discuss typical regimens for the two most common organisms: Staphylococcus and Streptococcus.

Staphylococcus aureus

- Methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus (MSSA): flucloxacillin 12 g/day in 4-6 doses. Duration 4-6 weeks.

- Methicillin-resistance staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or penicillin allergy: vancomycin 30-60 mg/kg/day in 2-3 doses. Duration 4-6 weeks.

NOTE: in the presence of a prosthetic valve, rifampicin and gentamicin should be added to both regimens and the duration should be ≥6 weeks.

Streptococcal species

The following regimens are typically used for oral Streptococci and Streptococcus bovis. The regimen depends on how resistant the organism is to penicillin. This alters treatment duration, agent choice and need for combination therapy. If no resistance, the usual antibiotics may include:

- Standard four-week regimen: penicillin G, OR amoxicillin, OR ceftriaxone

- Standard two-week regimen: penicillin G, OR amoxicillin, OR ceftriaxone combined with gentamicin.

- Penicillin allergic: vancomycin for four weeks

Empirical therapy

When IE is highly suspected, but the organism is not yet known, empirical antibiotics can be started following three sets of blood cultures.

- Native valve endocarditis or late prothetic valve endocarditis: Ampicillin, flucloxacillin and gentamicin, OR vancomycin and gentamicin.

- Early prosthetic valve endocarditis: vancomycin, gentamicin and rifampicin.

Surgery

Up to 50% of patients with IE will require surgery during their inpatient hospital stay. The two main aims of surgery are removal of infected tissue and reconstruction of cardiac anatomy (i.e. valve repair or replacement).

There are numerous indications for surgery, which can broadly be divided into the following:

- Heart failure (e.g. new acute heart failure with haemodynamic compromise)

- Uncontrolled infection (e.g. abscess formation or persistently positive blood cultures)

- Prevention of embolisation (e.g. large vegetations >10 mm).

Based on the underlying indication, the urgency of surgery can be divided into three groups:

- Emergency surgery (within 24 hours)

- Urgent surgery (within a few days)

- Elective surgery (within 1-2 weeks of antibiotics therapy)

Endocarditis team

All patients with strongly suspected or confirmed IE should be referred to the IE team. This team includes, but not limited too, a cardiologist, cardiothoracic surgeon, microbiologist and nurse specialist.

Patients with complicated IE, which refers to IE with heart failure, abscess formation or embolic complications, need referral to a tertiary centre with cardiothoracic facilities.

Prevention

Patients high-risk of developing IE may be offered prophylactic antibiotics.

In 2008, NICE guidance recommended against the routine use of prophylactic antibiotics for certain procedures (e.g. dental) because of a poor evidence base and cost-ineffective. However, there is feeling that a small subgroup of patients at particularly high-risk may benefit from prophylactic antibiotics. This is a nuanced area and the European Society of Cardiology has an excellent summary on the topic.

If they are being considered, the risk/benefit needs to be considered including the procedure, patient and choice.

High-risk procedures

Prophylactic antibiotics may be prescribed to high-risk patients undergoing high-risk procedures.

High-risk procedures may include:

- Cardiac procedures (screening for S. aureus, perioperative prophylaxis may be needed, eliminate source of sepsis ≥2 weeks before procedure)

- Dental procedures (manipulation of gingival or perioapical region, local anaesthetic injections, treatment of superficial caries, tooth removal or orthodontic procedures)

- Respiratory tract procedures (bronchoscopy, laryngoscopy, transnasal or endotracheal intubation)

- Gastrointestinal procedures (transoesophageal echocardiography, gastroscopy, colonoscopy)

- Urological procedures (cystoscopy)

- Obstetric procedures (vaginal or caesarian delivery)

High-risk patients

Antibiotic prophylaxis may be used in sub-group of high-risk patients (if benefit is felt to outweigh risk). This group is defined as any patient with:

- Prosthetic heart valves or material used for cardiac valve repair

- Previous IE

- Congenital heart disease (any cyanotic heart disease, those with a lifelong shunt or valvular regurgitation)

Prophylactic antibiotics

Options for prophylactic antibiotics for dental procedures (if benefit is felt to outweigh risk) may include:

- No penicillin allergy: amoxicillin 2 g orally or IV 30-60 minutes before procedure

- Penicillin allergy: clindamycin 600 mg orally or IV 30-60 minutes before procedure

Complications

IE can be a life-threatening condition with development of numerous complications.

Heart failure is the most frequent and one of the most severe complications of IE. It is a common indication for surgery.

Complications include:

- Cardiac (50%): heart failure, perivalvular abscess, pericarditis, cardiac tamponade

- Neurological (80% - may be silent): stroke, abscess, meningitis, encephalitis, haemorrhage, seizures

- Metastatic infection: mycotic aneurysm, embolisation, abscess formation

- Embolisation sequelae: stroke, blindness, ischaemic limb, splenic/renal infarct, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction

Last updated: April 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback