Myocarditis

Notes

Overview

Myocarditis is inflammation (-itis) of the muscular layer of the heart (myocardium).

Myocarditis can be difficult both to understand theoretically and to diagnose clinically. This is due to myocarditis having:

- A wide range of causes

- A broad spectrum of clinical presentations

- A very variable disease course

In general, myocarditis is usually idiopathic or caused by a viral infection, although there are multiple other causes. The presentation and prognosis of myocarditis varies widely, from mild, self-limiting disease, to fulminant heart failure and associated high mortality.

We suggest reading our note on Pericarditis before reviewing Myocarditis since there are several similarities between the two topics.

Definitions

Myocarditis may be associated with inflammation in the pericardium.

- Myocarditis: inflammation of the myocardium, which is the muscular tissue of the heart.

- Perimyocarditis: inflammation of both the pericardial sac and myocardium with primarily myocarditic syndrome.

- Myopericarditis: inflammation of both the pericardial sac and myocardium with a primarily pericarditic syndrome.

The myocardium

The myocardium is the thickest layer of the heart.

Anatomy

The myocardium is considered the thickest layer of the heart and it is sandwiched between the endocardium deep to it, and the epicardium superficial to it. Contraction of the myocardium is responsible for the contraction of the atria and ventricles.

The myocardium is thicker in the ventricles as compared to the atria, reflecting the higher pressures that the ventricles must generate to pump blood against pressure in the pulmonary and systemic circulations.

Physiology

The myocardium functions as a syncytium – each cardiac myocyte is connected to its neighbours by intercalated discs. The intercalated discs allow the electrochemical signals associated with each heartbeat to pass smoothly throughout the myocardium. This arrangement allows the heart to contract in a coordinated manner, optimising cardiac output. This syncytial arrangement will be relevant when we look at some of the complications of myocarditis later in this topic.

Epidemiology

The exact incidence of myocarditis is difficult to estimate.

It is difficult to estimate the incidence of myocarditis, since – as we will see in “diagnosis and investigations” below – there is no easy way to diagnose myocarditis without invasive tests.

One estimate suggests myocarditis is relatively rare, accounting for 0.04% of hospital admissions in England between 1998 and 2017, although this is likely to be an underestimate.

Myocarditis is most common in young men.

Classification

Myocarditis is classified as acute or chronic.

- Acute myocarditis: develops over 3 months or less.

- Chronic myocarditis: develops over a longer than 3 months.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

In 50% of patients, the cause of myocarditis is never found.

In at least half of the cases of myocarditis, a cause cannot be identified. This is known as idiopathic myocarditis.

In the UK, when a cause for myocarditis is identified, it is usually a viral infection of the myocardium. Coxsackie virus is the most common viral culprit, although many other viruses can cause myocarditis including adenovirus, parvovirus B19, EBV, and HIV.

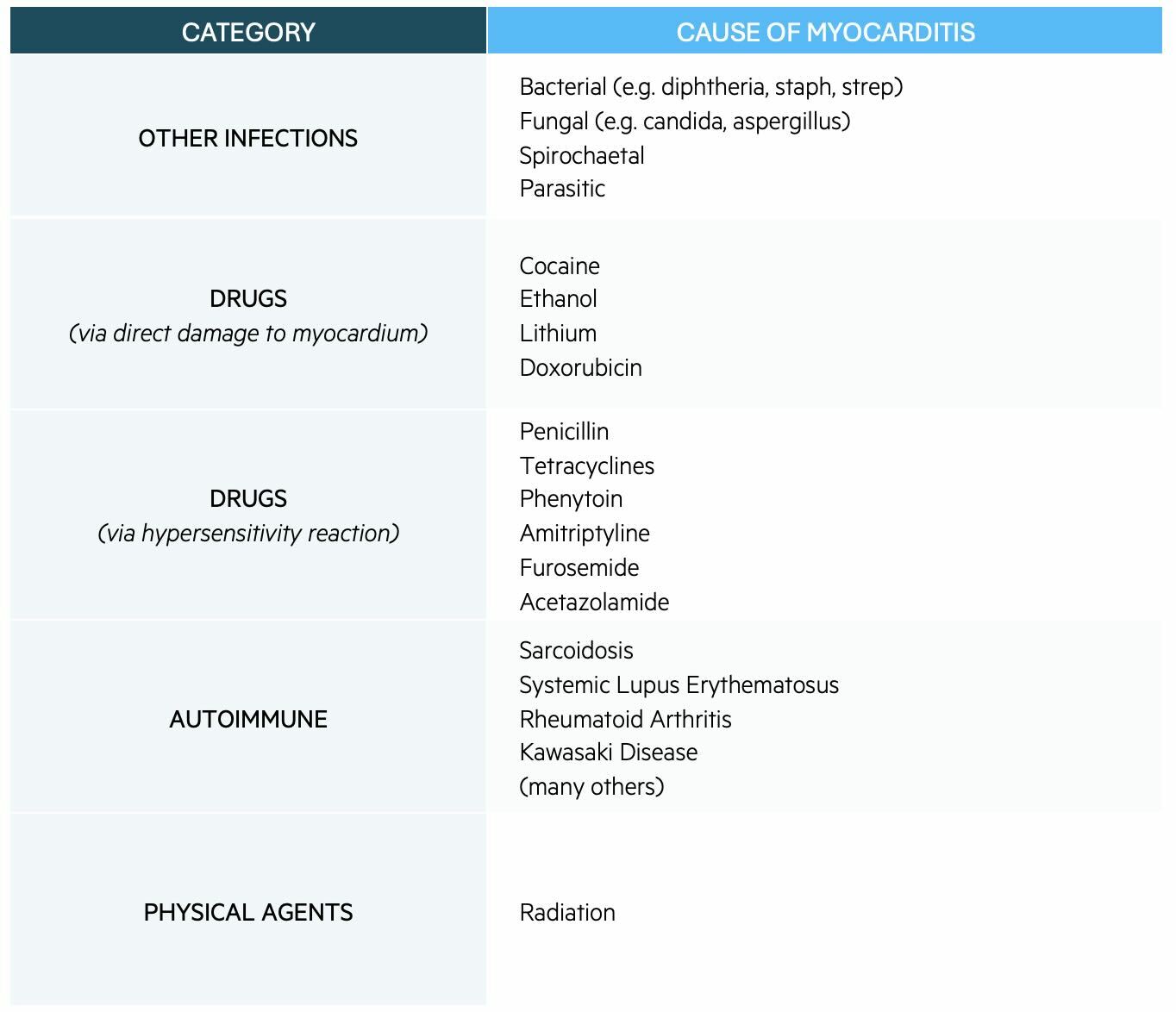

Other causes of myocarditis are shown in the table below:

Pathophysiology

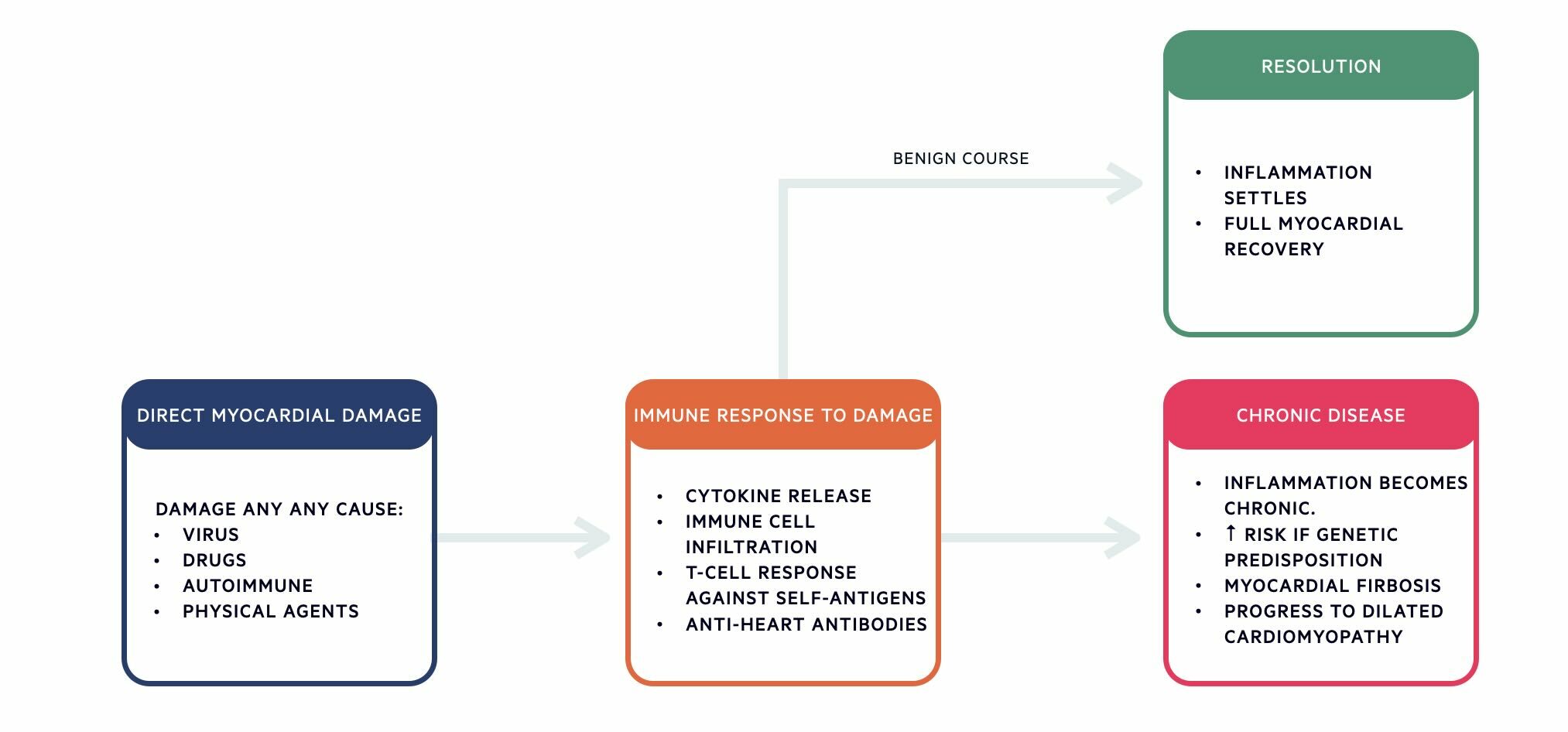

The pathophysiology of myocarditis is divided into three main stages:

- Direct myocardial damage

- Immune response to damage

- Resolution OR chronic disease

Clinical features

The presentation of myocarditis varies greatly, ranging from mild symptoms to life-threatening cardiac conditions.

Features of mild myocarditis

- Fatigue

- Chest pain: can resemble chest pain seen in acute coronary syndromes (e.g. central, heavy or squeezing, and radiating to the jaw or arm).

- Pleuritic pain: Myocarditis can also be associated with pericarditis. If this is the case, chest pain might point towards pericardium (e.g. central, pleuritic, and relieved by leaning forward).

- Dyspnoea

- Fever

- Palpitations

- Features of recent respiratory illness (e.g. myalgia, cough, coryzal symptoms).

- Features suggestive of recent gastrointestinal infection (e.g. vomiting, diarrhoea).

Features of severe myocarditis

- Acute heart failure (Fatigue, dyspnoea, orthopnoea, elevated JVP, and peripheral oedema).

- Cardiogenic shock (i.e. low blood pressure due to impaired cardiac function).

- Arrhythmias (palpitations, lightheadedness, or syncope). Remember, inflammation of the cardiac myocytes will disrupt the flow of each actional potential through the heart, and so can contribute to arrhythmias.

- Dilated cardiomyopathy

- Sudden cardiac death

Diagnosis & investigations

The only way to definitively diagnose myocarditis is via endomyocardial biopsy.

Definitive Diagnosis of Myocarditis

The only way to categorically diagnose myocarditis is via endomyocardial biopsy (EMB):

- A catheter is passed through a vein or artery into the right or left ventricle.

- Once in the ventricle, specialised small pincers are used to take samples of the heart muscle.

- These samples can be sent to the lab to look for evidence of viral infection and inflammatory changes.

Taking biopsies from the myocardium is not without risk – risks of EMB include accidental perforation of the myocardium (which can lead to pericardial tamponade), arrhythmias, and pneumothorax.

Because of the risks of EMB, it is not routinely used to diagnose myocarditis. Instead, it is only performed if the results are likely to change patient management. This is usually the case when:

- Other causes of heart failure have been excluded.

- A patient has presented with unexplained fulminant heart failure.

- A failure to respond to treatment.

If EMB provides evidence of myocarditis, then we can make a “definitive diagnosis of myocarditis”.

Clinically Suspected Myocarditis

For most patients, we have to settle for a diagnosis of “clinically suspected myocarditis”. For these patients, initial investigations include:

- Bedside

- ECG: A normal ECG does not rule out myocarditis and the condition may be associated with a range of ECG changes including ST elevation (most common), ST depression, T wave inversion, ectopic beats, tachycardias.

- Bloods

- Troponin: Elevated due to inflammation and damage of cardiac myocytes. However, a normal troponin does not exclude myocarditis

- Inflammatory markers: WCC, CRP and ESR are likely to be raised, reflecting the underlying inflammatory process.

- BNP: Will be raised in the presence of heart failure. Remember, BNP is released by the ventricles in response to fluid overload and ventricular stretch.

- Imaging

- CXR: Often normal, but may show signs suggestive of heart failure (i.e. cardiomegaly, pulmonary oedema)

- Echocardiography: Can detect impaired ventricular function. This may appear as dilated ventricle, poor ejection fraction, or wall motion abnormalities (i.e. part of the ventricular wall does not contract in time or as strongly as expected) An echocardiography is also important to exclude other structural causes of symptoms (e.g. valvular disease).

- Cardiac MRI: This is one of the most helpful tests after EMB. There are typical features of inflammatory hyperemia and edema, myocyte necrosis and scar formation, changes in ventricular size and shape, and regional and/or global wall motion abnormalities (including quantification of LVEF).

- Special tests

- Coronary angiogram: If ACS is a differential diagnosis, patients may undergo an angiogram to exclude coronary artery disease.

Management

The treatment of myocarditis is largely supportive and depends on the underlying cause.

There are two ways to think about the treatment of myocarditis:

- General supportive measures for all patients with myocarditis vs. measures that target specific underlying causes of myocarditis.

- Management of relatively well or asymptomatic patients vs. critically unwell patients who – for example – present in acute heart failure.

General supportive measures

- Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Animal studies suggest NSAIDs might aggravate myocarditis and increase mortality.

- Avoid heavy alcohol consumption: A heavy alcohol intake can contribute to the worsening of myocarditis. No studies have been performed to establish a ‘safe’ limit, so total abstinence or a maximum of 2 units of alcohol per day is sensible.

- Avoid exercise*: Exercise causes several problems for the inflamed myocardium:

- Increased work and oxygen demand.

- Increased viral replication.

- Risk of fatal ventricular arrhythmias.

- Anticoagulants when appropriate (e.g. systemic emboli, left ventricular thrombus, atrial fibrillation with elevated CHA2DS2-VASc score)

*NOTE: The American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation suggest three to six months of abstinence from competitive sports after myocarditis.

Measures targeting the specific underlying cause

If a non-viral infectious agent is identified, this should be treated. One example of such a condition might be myocarditis secondary to Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi)

Measures for critically unwell patients

For patients presenting with acute heart failure:

- If haemodynamically stable, give:

- Diuresis (e.g. furosemide)

- ACE inhibitor

- Beta blocker (e.g. bisoprolol)

- If haemodynamically unstable,

- Contact intensive care.

- Inotropes may be required to support cardiac function.

- Mechanical support devices (e.g. a left ventricular assist device) may be needed.

- Cardiac transplantation may be considered in specific cases.

All patients with acute or unstable myocarditis should be admitted and monitored for arrhythmias. The general management should follow the ALS guidance on the management of tachyarrythmias. In general, restoring sinus rhythm is first-line, and rate control is second-line. Sustained ventricular arrhythmias should be cardioverted urgently, as per UK Resuscitation Council guidelines.

Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators are not usually indicated in acute myocarditis since – once the inflammation settles – the arrhythmias usually settle too.

Prognosis

Most patients with acute myocarditis will recover without long-lasting effects.

The more unwell a patient is on initial presentation, the higher their risk of chronic cardiac problems (e.g. dilated cardiomyopathy) and/or mortality. Markers of increased severity on presentation include:

- Reduced left ventricular function (i.e. ejection fraction < 50%).

- Sustained ventricular arrhythmias.

- Heart failure and low cardiac output requiring inotropic or mechanical support.

Last updated: September 2024

References:

-

UpToDate – Myocarditis: Causes and pathogenesis

-

Brociek, E. et al. Myocarditis: Etiology, Pathogenesis, and Their Implications in Clinical Practice. Biology 2023, 12, 874. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12060874

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback