Atopic eczema

Notes

Introduction

Atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) is a common inflammatory skin condition that typically presents early in life.

Atopic eczema normally presents in the first few years of life and normally follows a relapsing-remitting course. It is characterised by a dry, cracked and itchy rash that may follow a number of patterns of distribution. Episodic flares are followed by periods of remission, though the interval and length of episodes vary widely and some patients develop chronic disease without remission.

Management tends to follow a stepped approach that involves emollients and additional agents such as topical steroids, antihistamines and oral steroids where needed. Complications include secondary infection and the impact of the condition on patients quality of life and mental wellbeing.

Epidemiology

Atopic eczema is thought to affect 10-30% of children and 2-10% of adults.

The Global Report on Atopic Dermatitis in 2022 suggested that the condition affects up to 20% of children and 10% of adults. However, this differs significantly between countries with the highest prevalence occuring in Sweden and the United Kingdom.

The majority of cases present early in life with a prevalence per 100,000 of the population almost 7x higher in 1-4 year old compared to adults.

The condition appears more common in those in higher socioeconomic classes and with smaller families. It occurs in all ethnic groups and does not show any significant gender imbalance.

Atopy

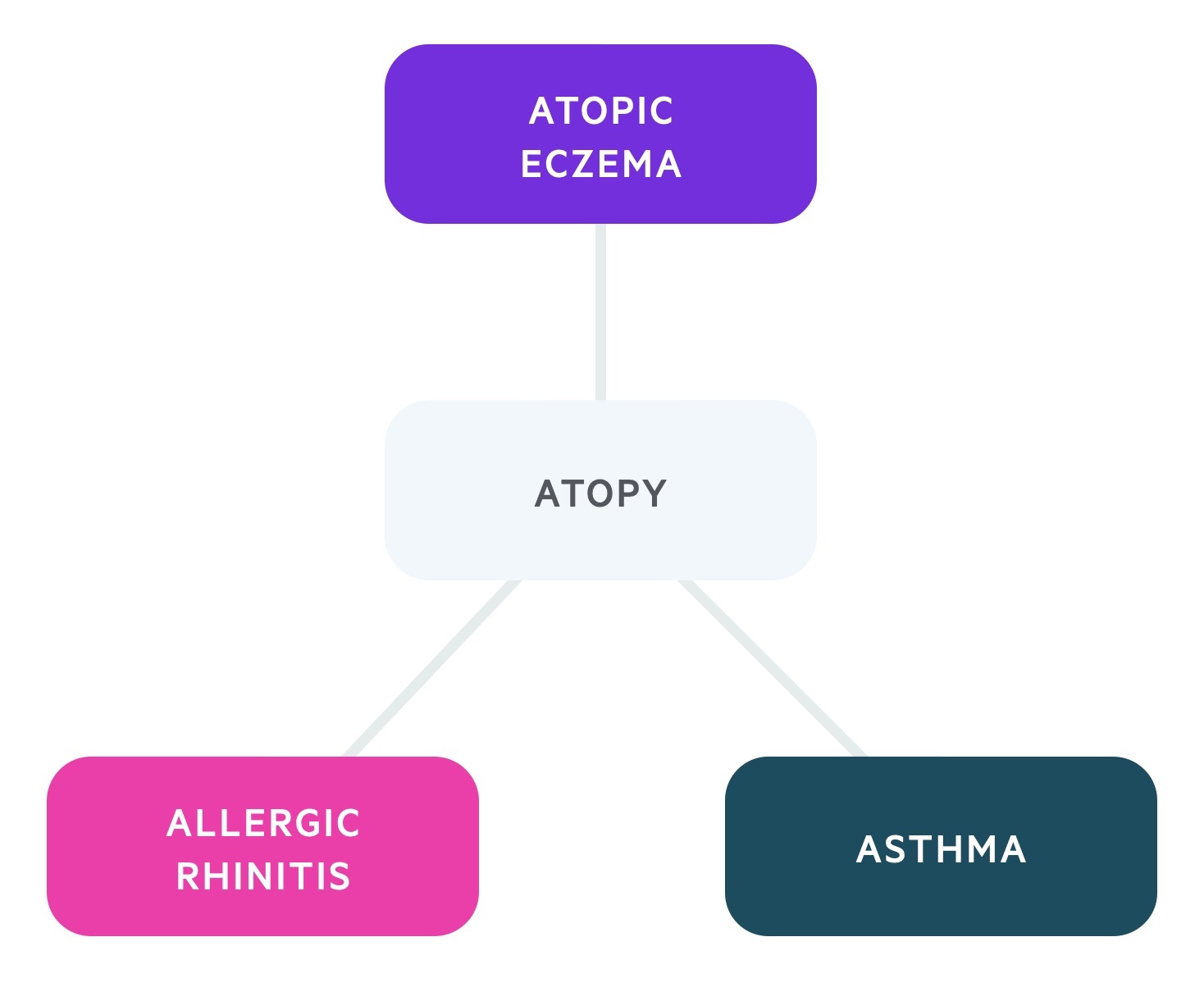

Atopy refers to a predisposition to an abnormally exaggerated IgE response to allergen exposure.

Atopy involves the sensitisation to allergens/antigens that are detected by CD4+ type 2 helper (Th2) lymphocytes causing their differentiation and resulting in an exaggerated IgE response. This leads to increased risk of hypersensitivity reactions.

Atopic individuals are classically said to be at risk of developing a triad of conditions; atopic eczema, allergic rhinitis and asthma. Other conditions include food allergies and allergic conjunctivitis. The term ‘atopic march’ refers to the progressive development of atopic disease, often with atopic eczema presenting as an infant followed by asthma and/or allergic rhinitis early in childhood.

Aetiology

The aetiology of atopic eczema is complex and incompletely understood. It involves environmental, hereditary, and immunological factors.

A family history of atopic disease increases the risk of developing atopic eczema (as well as other atopic conditions). It is estimated that 70% of those with atopic eczema will have a family history of atopic disease. Twin studies have shown a concordance of 77-85% in monozygotic twins and 15-21% in dizygotic twins.

A mutation in the FLG gene has been implicated in up to 50% of cases. FLG encodes filaggrin, a protein required for skin to perform its role as an effective barrier. Deficiency is thought to allow access of antigens through the skin where they initiate an immune and inflammatory response.

Clinical features

The onset, appearance and distribution varies between individuals.

It often presents with scaly, itchy and erythematous patches commonly affecting the flexures (elbow, knees, wrists). Infants often present with rash affecting the cheeks.

Those of black ethnicity may demonstrate a different distribution with rashes affecting the extensor surfaces. Affected skin can develop patches of both hypo and hyperpigmentation.

Itchiness leading to scratching can be evidenced by excoriations and with time lichenification (thickening) of the skin develops.

Differentials

There are a number of other dermatological conditions that should be considered.

Alternative diagnosis should be considered and when necessary excluded. These include:

- Psoriasis

- Seborrhoeic dermatitis

- Fungal infections

- Contact dermatitis

- Scabies

Diagnosis

NICE have published diagnostic criteria for eczema in children under 12.

The diagnosis of atopic eczema is considered a clinical diagnosis based on characteristic features (dry, itchy, erythematous or thickened rash) in a typical distribution. Formal investigations should not routinely be required for the diagnosis. Be aware that atopic eczema may present with different distribution (e.g. extensor) or patterns (e.g. follicular) in patients of Asian, black Caribbean or black African ethnicity.

Based on the clinical features, atopic eczema can be divided into different forms of severity.

- Mild: areas of dry skin, infrequent itching (with or without small areas of redness)

- Moderate: areas of dry skin, frequent itching, and redness (with or without excoriation and localized skin thickening)

- Severe: widespread areas of dry skin, incessant itching, and redness (with or without excoriation, extensive skin thickening, bleeding, oozing, cracking, and alteration of pigmentation)

NICE CG 57 (2021 update) describe a set of features diagnostic of atopic eczema for children under the age of 12:

Atopic eczema should be diagnosed when a child has an itchy skin condition plus 3 or more of the following:

- visible flexural dermatitis involving the skin creases, such as the bends of the elbows or behind the knees (or visible dermatitis on the cheeks and/or extensor areas in children aged 18 months or under)

- personal history of flexural dermatitis (or dermatitis on the cheeks and/or extensor areas in children aged 18 months or under)

- personal history of dry skin in the last 12 months

- personal history of asthma or allergic rhinitis (or history of atopic disease in a first- degree relative of children aged under 4 years)

- onset of signs and symptoms under the age of 2 years (this criterion should not be used in children aged under 4 years)

Healthcare professionals should be aware that in Asian, black Caribbean and black African children, atopic eczema can affect the extensor surfaces rather than the flexures, and discoid (circular) or follicular (around hair follicles) patterns may be more common.

Management

The medical management of atopic eczema consists of a stepped approach with emollients forming the base of treatment.

Identifying triggers

Many individuals will have specific triggers that appear to cause flares of disease. This can include perfumes, detergents, soaps, clothes, hormones, foods and hormones.

Diaries may be of use to demonstrate temporal relationships between triggers and flares - in particular food diaries. Food allergies are more commonly seen in atopic individuals.

Medical management

Generally speaking a stepped approach to management is used. Emollients sit at the base of this approach with other agents added when indicated.

Emollients are moisturising agents that comes in the form of ointments, creams, sprays, lotions and soap substitutes. Regular and liberal use is advised even between flares of disease.

They help to soothe, smooth and hydrate skin in patients with both dry or scaling disorders. Their effects are short-lived and therefore regular application is critical.

There are many emollients and the choice depends on the severity, location and patient preference. The formulation of an emollient is often referred to as a 'vehicle'. For example, in topical hydrocortisone cream, hydrocortisone is the drug and the vehicle is the cream that helps it be applied. Emollients used alone do not have a drug (vehicle-only). A variety of vehicles may be used:

- Lotions (e.g. Dermol® 500 lotion, E45® lotion): high water content. Spread easily and cooling. Not effective at moisturising very dry skin. Quick absorption time.

- Creams (e.g. Diprobase® cream, Epaderm® cream): mixture of fat and water. Spread easily. Not as greasy so often preferred by patients. Need to be used frequently to help skin repair.

- Gels (e.g. Dermol® 500 lotion, E45® lotion): high oil content. Light and non-greasy. Need to be used frequently.

- Sprays (e.g. Emollin® spray): Useful for hard to reach areas. Small number of preparations available.

- Ointments (e.g. Diprobase® ointment, Epaderm ointment®): contain minimal water making them thick and greasy. Patients may find them cosmetically displeasing. Very effective at holding water and repairing skin. Should not use on weeping eczema.

Emollients may also be used as soap substitutes or added to baths/showers. Ordinary wash products can have the potential to irritate and damage skin.

Soap substitues can be used for hand washing, showering and bathing. Products may be prescribed that are specificaly designed for this use or usual emollients can be used. Bath and shower oil products may be bought over the counter. These can be added to baths or used directly during a shower. They likely provide limited benefit to usual emollient treatment.

Topical steroids are frequently used. These are categorised by their potency:

- Mildly potent: examples include hydrocortisone 0.1%, 0.5%, 1.0%, and 2.5%

- Moderately potent: examples include clobetasone butyrate 0.05% (Eumovate®)

- Potent: examples include betamethasone valerate 0.1% (Betnovate®)

- Very potent: examples include clobetasol propionate 0.05% (Dermovate®)

The use of more potent options is typically controlled by specialists. Patients requiring this level of treatment will normally meet the requirements of specialist referral. Local side effects are common and may include a burning sensation, thinning of skin, contact dermatitis, acne and depigmentation. Doses vary depending on location of the rash and patients/family should be given clear instructions.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus and pimecrolimus) may be used in moderate to severe disease with appropriate specialist input, typically when topical corticosteroids have failed. As the name suggests they inhibit calcineurin inhibitors, a chemical that normally activates T-lymphocytes.

- Topical tacrolimus: may be used in those aged 2 and over with moderate-severe disease and where topical corticosteroids have not controlled symptoms and there is a risk of important adverse effects from further topical corticosteroids (e.g. skin atrophy).

- Topical pimecrolimus: may be used in those aged 2-16 with moderate disease on the face and neck and where topical corticosteroids have not controlled symptoms and there is a risk of important adverse effects from further topical corticosteroids (e.g. skin atrophy).

NICE CG 57 (2021 update) describes the following stepped apprach to management:

- Mild:

- Emollients

- Mild potency topical corticosteroids

- Moderate:

- Emollients

- Moderate potency topical corticosteroids

- Topical calcineurin inhibitors

- Bandages

- Severe:

- Emollients

- Potent topical corticosteroids

- Topical calcineurin inhibitors

- Bandages

- Phototherapy

- Systemic therapy

Specialist referral should be made where disease is not well controlled, severe, affecting the face or where the diagnosis is uncertain. Patients affected by complications - infections or disease impacting quality of life - should also be referred.

Psychosocial wellbeing

The impact of atopic eczema on an individuals emotional wellbeing varies. At each assessment the impact of their disease on their mental health and quality of life should be assessed.

Where necessary further support, treatment, referral and review should be offered.

Complications

Complications of eczema include secondary infection and a negative impact on an individuals quality of life.

Infection

Breakdown in the skins normal barrier predisposes patients to infection. They are most commonly bacterial or viral in nature:

- Secondary S.aureus: patients present with crusty, oozing rash with associated erythema. Disease is often mild and antibiotics may be avoided in those who are systemically well. New supplies of emollients and topical corticosteroids should be given and regular review organised.

- Eczema herpeticum: herpes simplex virus can cause a disseminated, life-threatening infection. Patients present with punched out erosions and vesicles. They require immediate hospitalisation and specialist management.

Mental health

As discussed in the management section above it is important to be aware of, and assess for, the psychological effects eczema may be having.

Young children with eczema have been shown to have more behavioural difficulties and dependency on their parents. Support to both patients and their family should be given.

Prognosis

Atopic eczema has a tendency to improve as children grow older and transition into adolescence and adulthood.

As described above the development of atopic eczema as an infant increases the chance of developing other atopic conditions in childhood such as asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Atopic eczema normally improves as children grow up. It tends to follow a natural history of gradual resolution with the condition clearing in around 74% by the age of 16. Unfortunately some individuals will be affected well into adulthood and disease may even worsen.

Last updated: April 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback