Hypothyroidism

Notes

Overview

Hypothyroidism is a common endocrine condition caused by a deficiency in thyroid hormone.

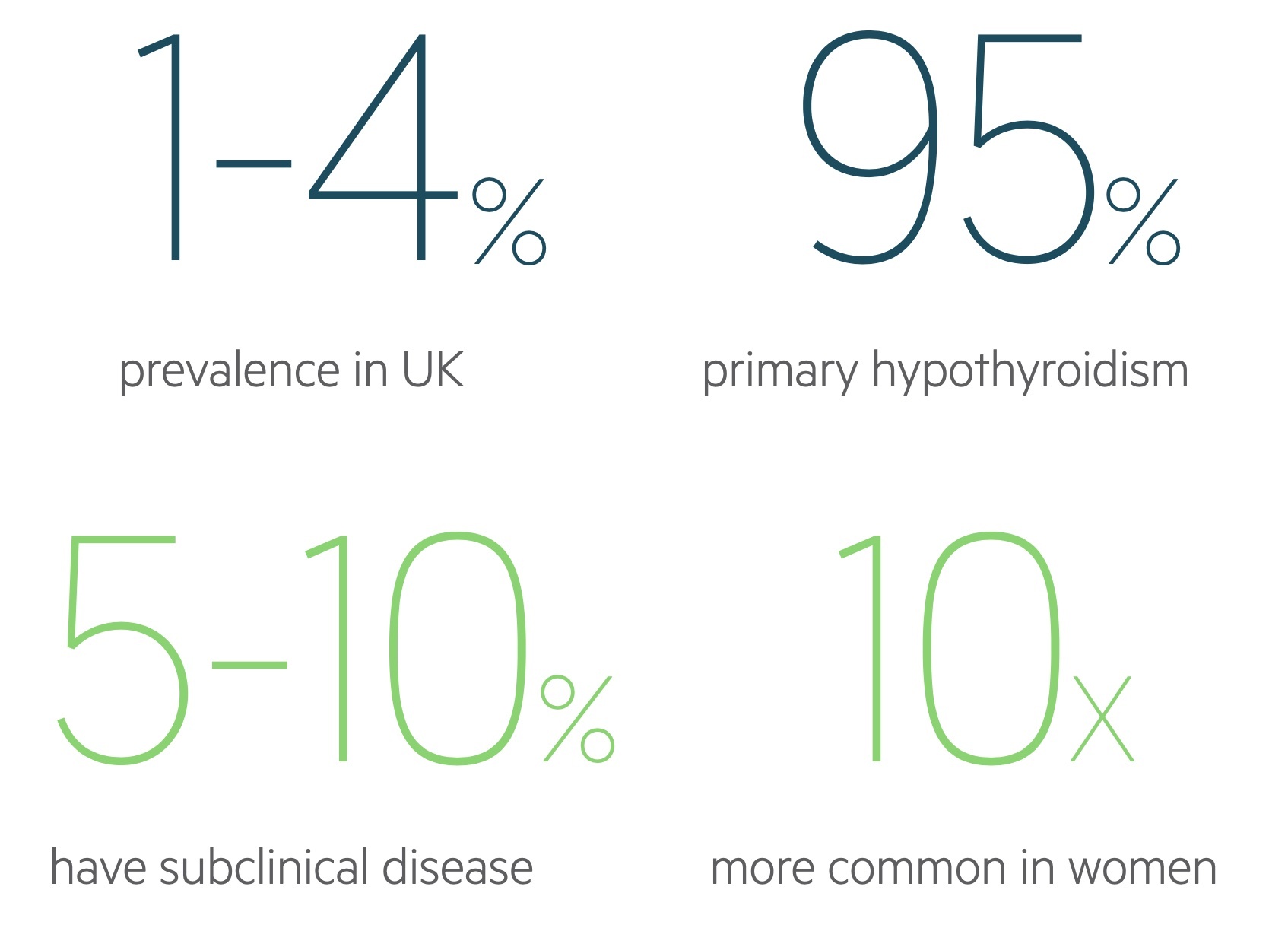

Hypothyroidism may be asymptomatic or present with often non-specific signs such as fatigue, weight gain, depression and cold intolerance. It has a prevalence of 1-4 per 100 in the UK and is up to 10 times more common in females.

Primary hypothyroidism - where disease is intrinsic to the thyroid gland - is responsible for around 95% of cases, it may be divided into:

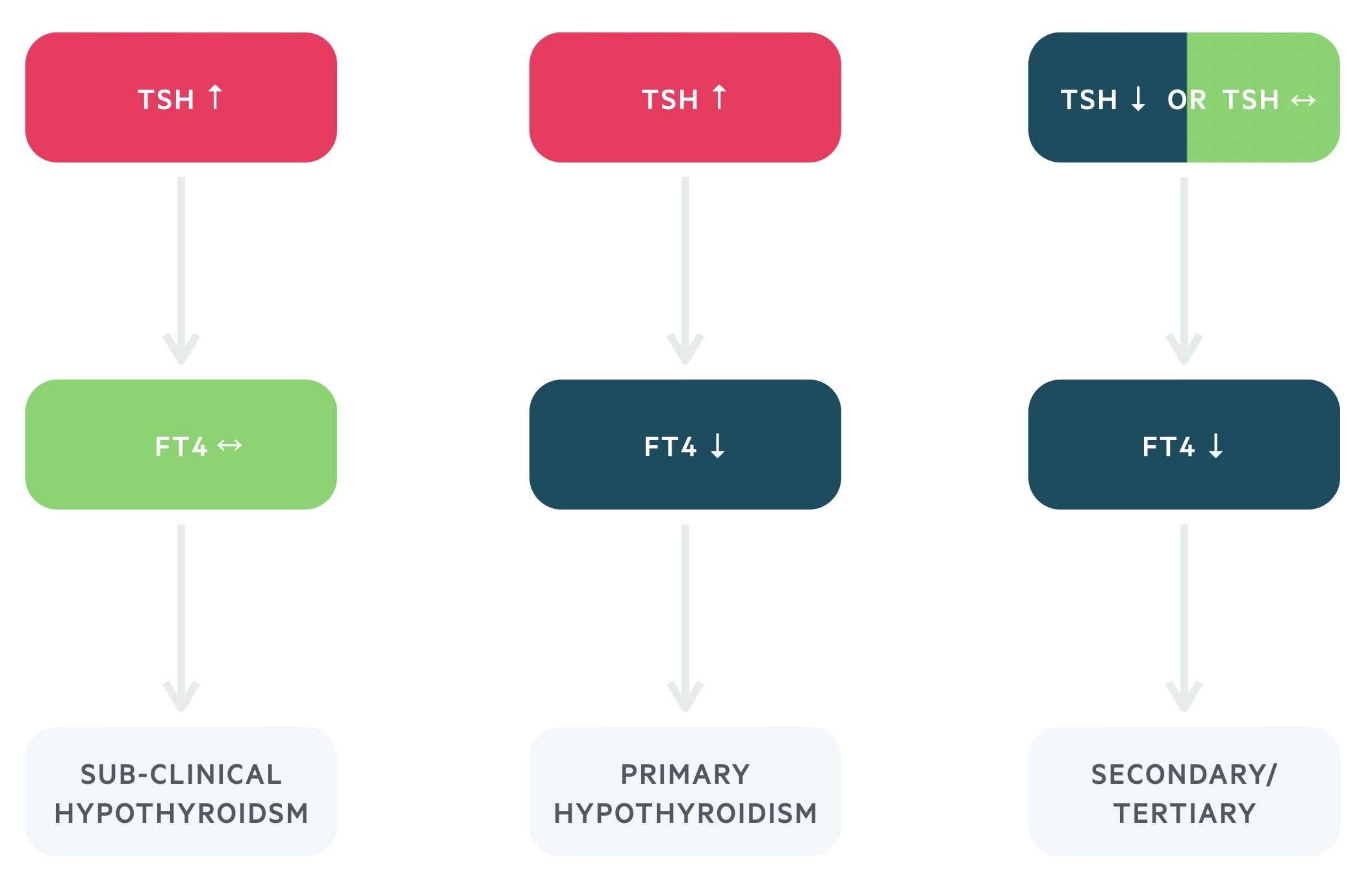

- Primary hypothyroidism (overt): Elevated thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels (typically > 10 mU/L) with a free T4 (fT4) level below the normal range.

- Subclinical hypothyroidism: The subclinical state is characterised by elevated TSH levels but T3/T4 that remains within the normal range.

Once diagnosed most patients respond well to thyroxine replacement therapy.

Thyroid physiology

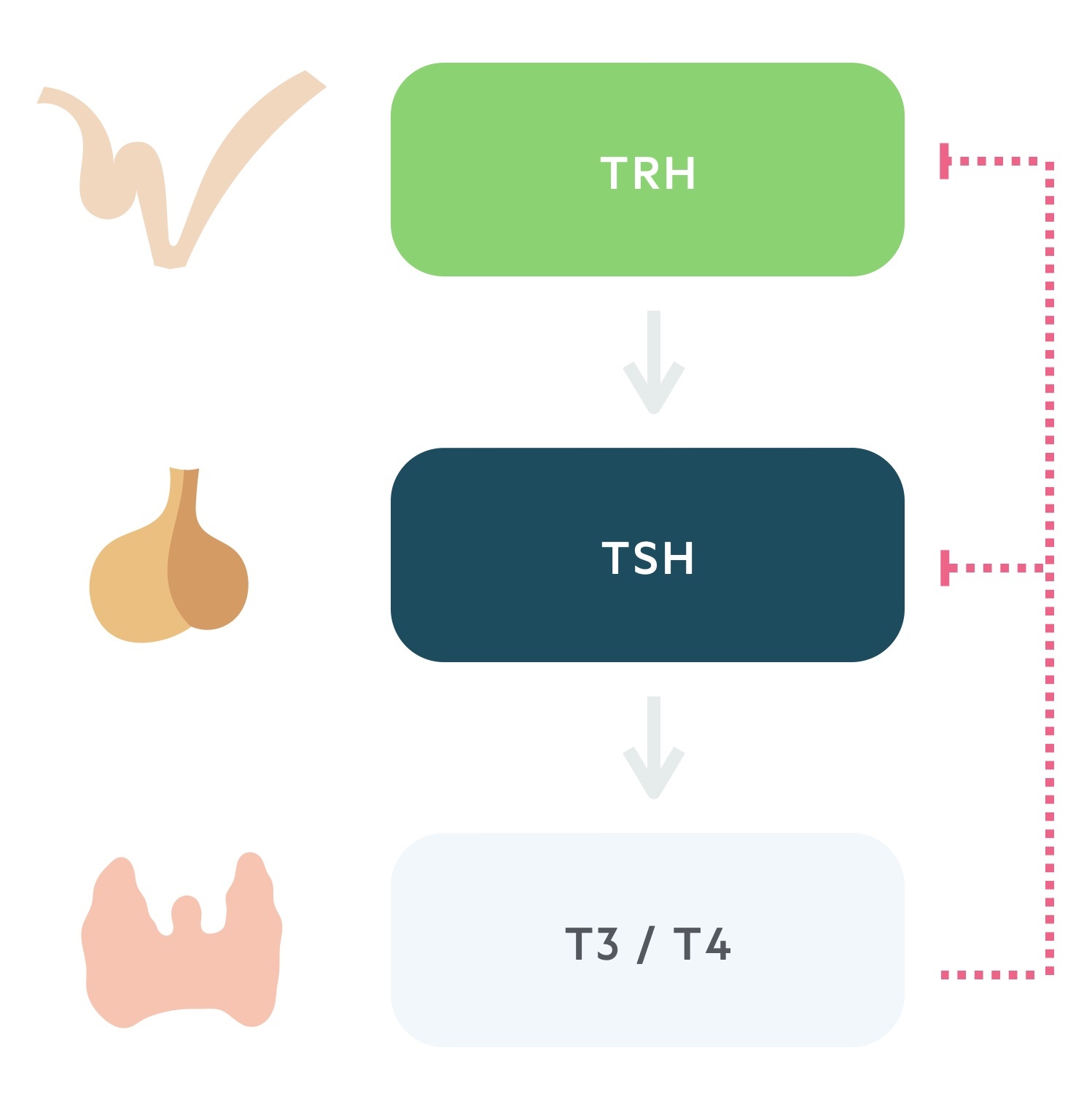

Thyroid hormone release is controlled by the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis.

1. Thyrotropin releasing hormone

TRH is secreted from the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. As the name suggests it is a tropic hormone i.e one that acts upon another endocrine gland.

It reaches the anterior pituitary via the hypophyseal portal system. Here it causes the release of thyroid stimulating hormone.

2. Thyroid stimulating hormone

TSH, produced by the thyrotrophs of the anterior pituitary, is released following stimulation by TRH.

Transported in the blood, TSH acts upon the thyroid gland promoting the synthesis and release of thyroid hormone.

3. Triiodothyronine and thyroxine

The thyroid is stimulated to synthesise and release thyroid hormone by TSH. The thyroid produces two hormones, thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3). These thyroid hormones complete a negative feedback loop through the suppression of TRH and TSH release.

Though T3 is more biologically active than its counterpart T4, secreted thyroid hormone is 90% T4. Peripherally much of T4 is converted to T3. Both are highly lipophilic, act on intracellular receptors and bind to thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG) in the blood. Only the ‘free pool’ is active: <0.1% T4 and <1% of T3.

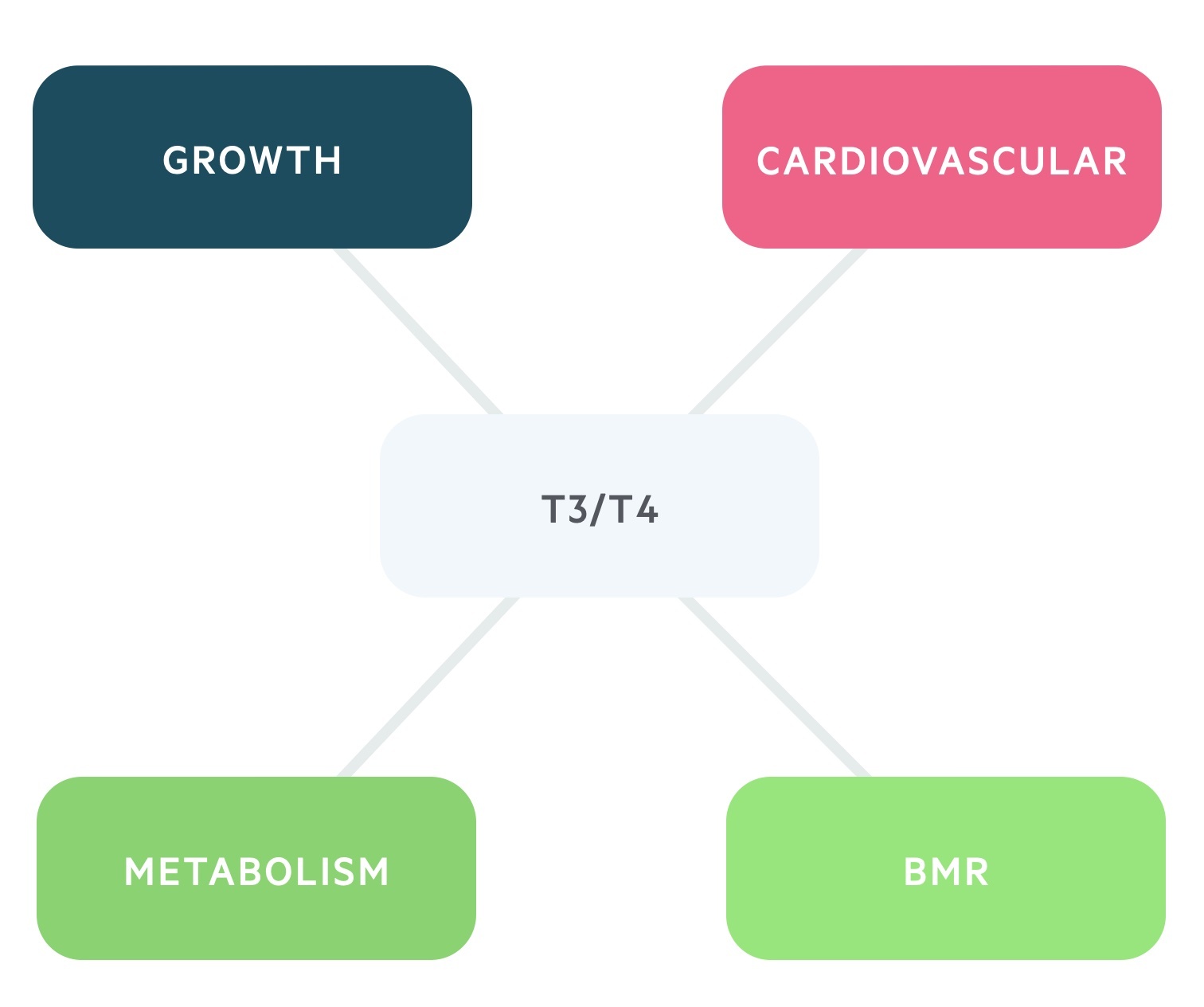

The effects to T3/T4 are numerous:

- BMR: increases the basal metabolic rate.

- Metabolism: it has anabolic effects at low serum levels and catabolic effects at higher levels.

- Growth: increases release and effect of GH and IGF-1.

- Cardiovascular: increases the heart rate and contractility through increasing sensitivity to catecholamines.

Aetiology

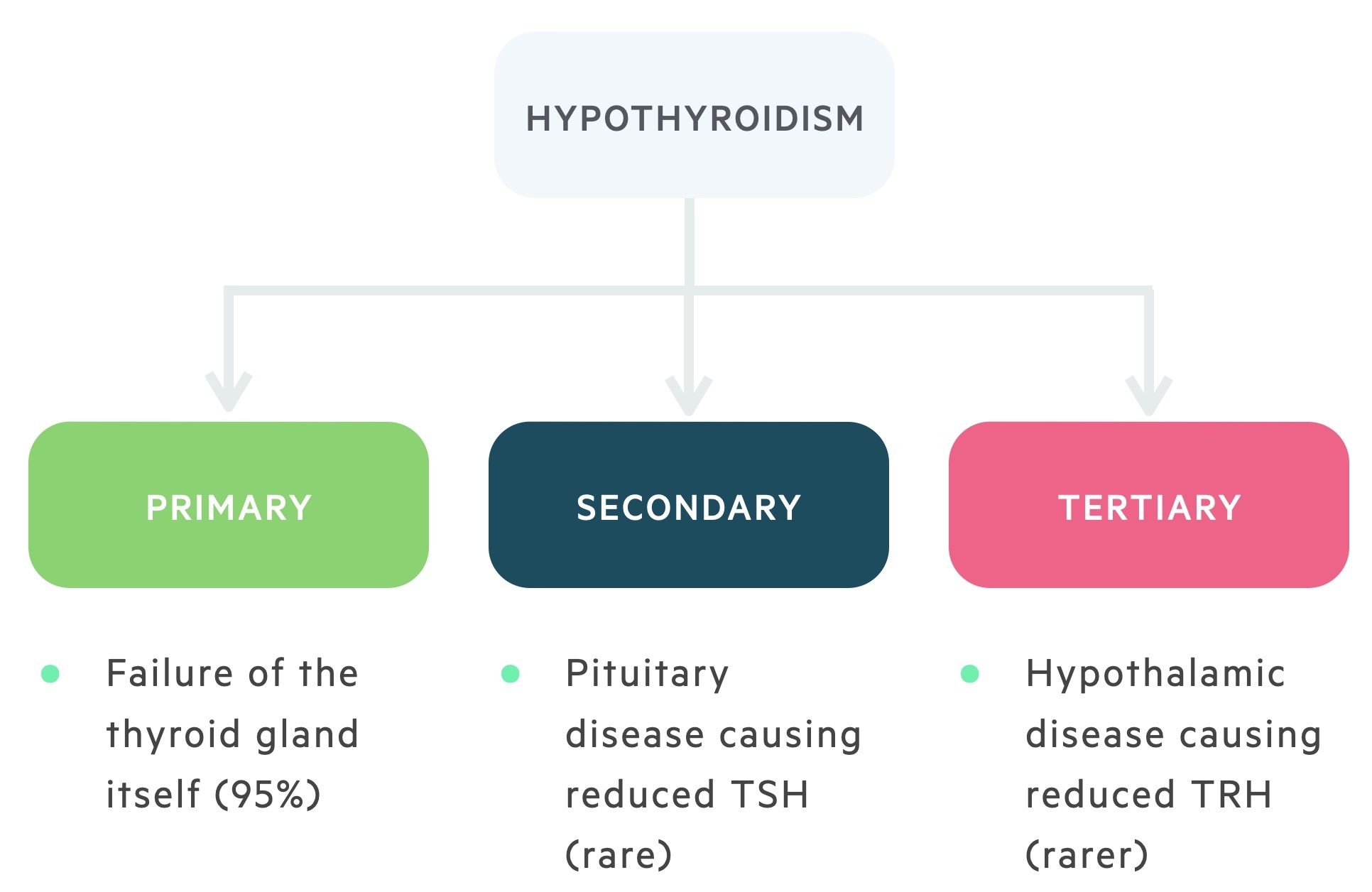

Hypothyroidism may be caused by disease affecting any part of the hypothalmic-pituitary-thyroid axis.

1. Primary hypothyroidism

The majority of cases of hypothyroidism are caused by disease intrinsic to the gland itself. This is termed primary hypothyroidism, it may be divided into:

- Primary hypothyroidism (overt): Elevated thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) levels (typically > 10 mU/L) with a free T4 (fT4) level below the normal range.

- Subclinical hypothyroidism: The subclinical state is characterised by elevated TSH levels but T3/T4 that remains within the normal range.

In primary hypothyroidism, we expect to find reduced levels of thyroid hormone accompanied by a raised TSH (due to lack of negative feedback).

2. Secondary hypothyroidism

Rarely disease or damage to the pituitary may reduce the production or release of TSH. This is termed secondary hypothyroidism. It is most frequently caused by pituitary adenomas.

In these conditions, we expect to find reduced levels of thyroid hormone accompanied by reduced TSH (due to lack of production).

In even rarer cases the TSH level is normal (or high) but the structural abnormalities cause the hormone to have less biological activity.

3. Tertiary hypothyroidism

Rarely disease or damage to the hypothalamus or the hypophyseal portal system may reduce the production, release or transport of TRH. This is termed tertiary hypothyroidism.

In this condition, we expect to find reduced levels of thyroid hormone accompanied by reduced TSH and TRH.

Resistance to thyroid hormone

In rare circumstances, individuals may suffer from resistance to thyroid hormone. This genetically inherited disorder is caused by an unresponsive form of one of the T3 receptors.

It is characterised by raised levels of thyroid hormone and TSH (as negative feedback is somewhat inhibited by hormone resistance).

This compensatory increase means most individuals are clinically euthyroid.

Primary hypothyroidism

Autoimmune disease is the most common cause of primary hypothyroidism in the western world.

Chronic autoimmune (Hashimoto’s) thyroiditis

In chronic autoimmune thyroiditis cell and antibody mediated processes cause destruction of the thyroid gland. It exists in two forms:

- Goitrous: characterised by a firm and rubbery goitre

- Atrophic: characterised by an atrophic gland

It is estimated to affect between 0.5% and 2% of the population. It is most frequently seen in women and becomes increasingly common with age.

The condition is associated with a number of other autoimmune conditions such as type 1 diabetes mellitus. Other associations include the genetic conditions Turner's and Down's syndrome.

Iodine deficiency

Worldwide, iodine deficiency is the leading cause of hypothyroidism. Iodine is a key component of thyroxine and its deficiency results in ‘endemic’ goitres.

This has led to a number of countries opting to fortify food products with iodine e.g Salt.

Postpartum thyroiditis

This is typically a transient change that occurs in the six months following birth, it may be preceded by a period of hyperthyroidism.

The condition is thought to affect between 6-10% of women with an increased incidence in diabetic patients.

Most women will show complete resolution of the condition.

Amiodarone-induced hypothyroidism

Amiodarone is a lipophilic class III anti-arrhythmic drug with a high iodine content. Its effects on the thyroid can be alarming and it may cause both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism.

The effects of amiodarone are dependent on whether there is pre-existing thyroid disease:

- Pre-existing autoimmune disease: hypothyroidism may occur secondary to the Wolff–Chaikoff effect - a phenomenon in which raised iodine intake results in reduced levels of thyroid hormone.

- Normal thyroid gland: those with a normal gland may also develop hypothyroidism, frequently affecting T3.

Congenital hypothyroidism

Congenital hypothyroidism is screened for with the Guthrie screen to prevent cretinism (the syndrome caused by congenital hypothyroidism). It may be due to:

- Dyshormonogenesis

- Abnormal gland development

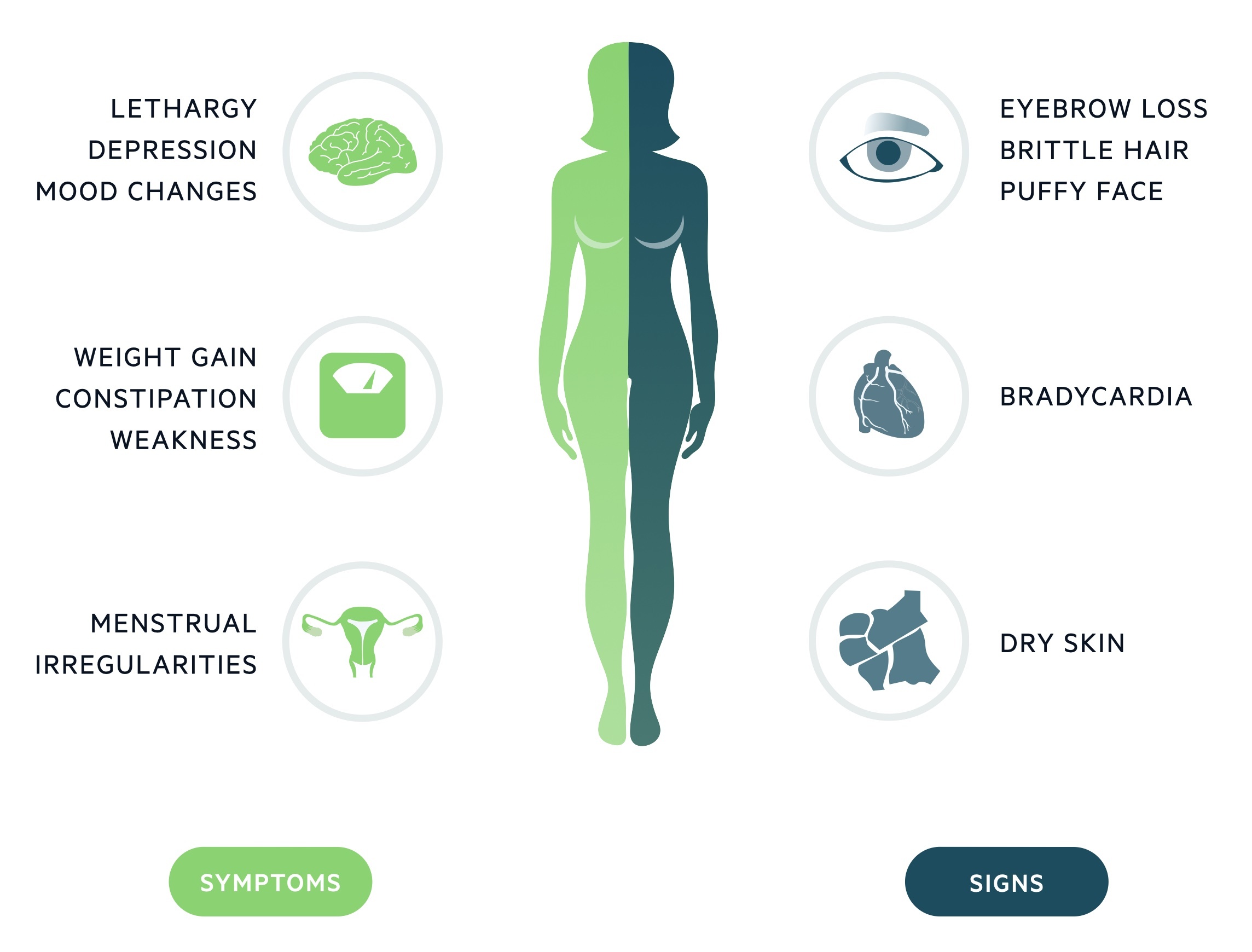

Clinical features

Hypothyroidism presents with non-specific symptoms, though patients may complain of a goitre.

Symptoms

- Tiredness

- Lethargy

- Weight gain

- Cold intolerance

- Menstrual irregularities (oligomenorrhoea, amenorrhoea, menorrhagia)

- Reduced libido

- Goitre

Signs

- Hair loss (characteristically the outer third of the eyebrows)

- Dry skin

- Goitre

- Bradycardia

- Myxoedema (deposition of mucopolysaccharides in the skin leading to swelling)

- Delayed relaxation phase of deep tendon reflexes

Investigations & diagnosis

Measurement of TSH and fT4 is usually sufficient to diagnose hypothyroidism.

Thyroid profile

TSH levels are the single most important diagnostic test. If the TSH level is elevated free T4 (fT4) can be added to the same sample. In primary hypothyroidism the TSH is elevated, this occurs secondary to reduced negative feedback from thyroxine (as levels are reduced). In very rare cases disease occurs due to pituitary or hypothalamus pathology, here the TSH is low or inappropriately normal (it should be elevated in the context of reduced T3/4).

- Primary hypothyroidism: raised TSH and reduced fT4.

- Secondary or tertiary hypothyroidism: normal (inappropriately normal) or lowered TSH or TRH and a reduced fT4.

Subclinical hypothyroidism refers to a raised TSH but normal fT4. Some individuals may have symptoms that could be caused by this biochemical picture.

Autoantibodies

A number of antibodies may be detectable in autoimmune thyroiditis.

- Anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) antibodies: consider in those with TSH above the reference level. It is often elevated in chronic autoimmune (Hashimoto’s) thyroiditis. However, it is non-specific and can also be elevated in conditions like Graves' disease as well as being seen in otherwise normal individuals.

- Anti-thyroglobulin (Anti-Tg) antibodies: commonly elevated in chronic autoimmune (Hashimoto’s) thyroiditis, levels are not routinely sent.

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies (TSHR-Ab): this is classically seen in Graves' disease where it is implicated in causing excess thyroid hormone production and release. They can also be present in chronic autoimmune (Hashimoto’s) thyroiditis, however, here they appear to block TSH- receptors preventing their activation.

Other

- FBC

- B12 and Folate

- Serum lipids

- HbA1c

- Coeliac serology

Suspicion of malignancy

- Ultrasonography

- Specialist referral (urgent two week wait)

Management

Replacement of thyroxine is the mainstay of management.

NICE guideline (NG145): Thyroid disease: assessment and management (published 2019, last accessed 2021) outline the management principles for primary hypothyroidism.

Levothyroxine, a synthetic version of T4, is the main treatment of primary hypothyroidism. NICE does not advise the routine use of liothyronine (a synthetic version of T3) as evidence of superiority over levothyroxine and long-term safety data is lacking.

18 - 65 years of age

The initial dose of levothyroxine is typically 1.6 mcg/kg (to the nearest 25mcg) with a TSH target of 0.4–4.5 mU/L.

The dose is titrated up and down by 25 mcg as needed. TSH levels are checked every 2-3 months then yearly once stable.

Over 65 or with cardiovascular risk factors

The initial dose of levothyroxine is typically 25 - 50 mcg with a TSH target of 0.4–4.5 mU/L.

The dose is titrated up and down by 25 mcg as needed. TSH levels are checked every 2-3 months then yearly once stable.

Pregnancy

Treatment should be started, typically a lower (and trimester dependent) TSH target is used. It requires specialist referral and management.

Subclinical hypothyroidism

Typically prompts further confirmatory test at 3-6 months. Treatment is not routine and monitoring for overt hypothyroidism is required.

It may be treated if the patient is symptomatic, has a goitre, rising TSH (or TSH > 10) or is pregnant (requires specialist referral).

Myxoedema coma

Myxoedema coma is a rare but potentially fatal outcome of untreated/undertreated hypothyroidism.

The term is a misnomer as myxoedema may not be present and the patient may not be comatose.

It is a medical emergency requiring admission to hospital and often results from acute decompensation during an intercurrent illness. Patients are hypotensive, hypothermic, bradycardic and demonstrate cognitive decline.

IV levothyroxine is the mainstay of management. Electrolyte imbalances and hypothermia should be addressed. IV hydrocortisone may be needed unless hypopituitarism is ruled out as a cause.

Last updated: November 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback