Phaeochromocytoma

Notes

Overview

Phaeochromocytoma refers to a catecholamine-secreting tumour of chromaffin cells.

Chromaffin cells are a type of neuroendocrine cell that are involved in the formation and release of catecholamines, which include noradrenaline, adrenaline and dopamine. These hormones have an important role in the sympathetic nervous system as part of the ‘fight-or-flight’ response.

Chromaffin cells are predominantly found in the adrenal medulla, but also in the sympathetic paravertebral ganglia of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis.

Catecholamine-secreting tumours

Catecholamine-secreting tumours may arise from the adrenal medulla or from the sympathetic ganglia and are known as phaeochromocytomas and paragangliomas respectively:

- Phaechromocytoma: arising from the adrenal medulla, accounts for 80-85% of such tumours.

- Catecholamine-secreting paraganglioma: arising from the sympathetic ganglia, accounts for 15-20% of such tumours. Sometimes referred to as ‘extra-adrenal phaeochromocytomas’.

Paragangliomas

Paragangliomas may arise from both parasympathetic and sympathetic ganglia. Paragangliomas affecting parasympathetic ganglia are commonly referred to as head and neck paragangliomas. They are usually non-secretory, derived from non-chromaffin cells and named after the tumour location (e.g. carotid body, glomus tympanicum, glomus jugulare).

Epidemiology

Phaeochromocytomas and paragangliomas are rare tumours.

Phaeochromocytomas account for < 0.2% of patients with hypertension. They most commonly present in the 4th or 5th decade, but at a younger age in hereditary cases. Around 10% of cases occur in children.

The majority of tumours are sporadic, but up to 40% have a hereditary component.

Aetiology

Phaeochromocytomas may be sporadic or hereditary.

Patients with sporadic phaechromocytoma are more likely to be older and present with classic features. This is because screening for phaeochromocytoma is more well established in hereditary cases. Several susceptibility genes have been identified in phaeochromocytoma. As such, genetic testing should be considered in all patients, usually following resection.

Up to 40% of phaeochromocytomas may have a hereditary component. Three familial syndromes are strongly associated with these catecholamine-secreting tumours:

- Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 2: autosomal dominant disorder due to a RET proto-oncogene mutation characterised by medullary thyroid cancer, phaechromocytoma and primary hyperparathyroidism. Phaechromocytoma is seen in 50% of cases. See our MEN syndromes notes for more details.

- Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome: autosomal dominant disorder due to VHL genetic mutation. Characterised by multiple tumours types including phaeochromocytoma, paraganglioma, hemangioblastoma (often involving cerebellum), renal cell carcinoma and many others. Phaeochromocytoma is seen in 10-20% of cases and frequently bilateral.

- Neurofibromatosis (NF) type 1: autosomal dominant disorder due to a mutation in the NF1 gene. Characterised by multiple neurofibromas, cafe au lait spots, axillary and inguinal freckling, central nervous system gliomas and phaeochromocytomas in around 3% of cases.

Pathophysiology

Phaeochromocytomas are neuroendocrine tumours arising from chromaffin cells.

The clinical manifestations of phaeochromocytomas are due to excess secretion of catecholamines from tumours leading to either paroxysmal or continuous symptoms. Catecholamines have wide-ranging effects as part of the normal sympathetic nervous system through activation of alpha and beta-adrenergic receptors. These effects include:

- Alpha-adrenergic: elevated bloods pressure, increased cardiac contractility, increased glucose utilisation (glycogenolysis/gluconeogenesis).

- Beta-adrenergic: increased heart rate, increased cardiac contractility.

The release of catecholamines from these tumours is not regulated and can be precipitated by direct pressure, medications or changes in tumour blood flow. The major concern is a sudden dramatic release in catecholamines leading to a 'hypertensive' or 'phaeochromocytoma' crisis.

Precipitants of hypertensive crisis

- Drugs: opiates, dopamine antagonists, beta-blockers, cocaine, tricyclic antidepressants

- Physical: direct pressure or handling during surgery

- Anaesthesia: endotracheal intubation

Tumour characteristics

There are some key characteristics about phaeochromocytomas and paragangliomas.

- Locations: >95% are located within the abdomen with up to 90% of these are intra-adrenal (i.e. phaeochromocytomas)

- Laterality: multiple tumours are seen in 5-10% of cases and hereditary cases are more likely to be bilateral

- Malignant potential: ~10% of cases are malignant. Malignant spread may occur a long-time following resection.

Clinical features

Phaeochromocytomas are characterised by a triad of episodic headache, sweating and tachycardia.

Classically, clinical features of phaeochromocytoma are paroxysmal. However, some patients may have more persistent symptoms, while others are asymptomatic. Important to remember that even patients with essential hypertension may have paroxysmal symptoms.

Symptoms

- Asymptomatic (50%): may be found incidentally on imaging or at autopsy

- Headache (90% in symptomatic): variable in duration and intensity

- Sweating (60-70% in symptomatic)

- Tachycardia

- Palpitations

- Dyspnoea

- Weakness

- Tremor

- Nausea

NOTE: symptoms may resemble those of a panic attack (e.g. nausea, palpitations, dyspnoea, sweating). Many patients worked up for phaeochromocytoma meet the criteria for panic disorder.

Signs

- Hypertension (paroxysmal in 50%)

- Posturla hypotension

- Weight loss

- Pallor

- Arrhythmias

- Pulmonary oedema: crackles at both lung bases

- Fever

- Tremor

Hypertensive crisis

Patients may develop severe symptoms relating to a hypertensive crisis, also known as a phaeochromocytoma crisis. If severe, it may lead to circulatory collapse.

- Hypertension

- Hyperthermia

- Confusion

- End-organ dysfunction (e.g. cardiomyopathy, pulmonary oedema)

- Hypotension (if circulatory collapse)

Who to test

All patients with a family history or hereditary condition associated with phaeochromocytoma need screening.

The following features warrant testing/screening for phaeochromocytoma:

- Classic triad (episodic headache, sweating and tachycardia)

- Hyperadrenergic spells (paroxysmal palpitations, sweating, headache, tremor, pallor)

- Atypical hypertension (e.g. early-onset, resistant to treatment)

- Associated familial syndrome

- Family history of phaeochrocytoma

- Typical adrenal adenoma on imaging

- Other

Biochemical investigations

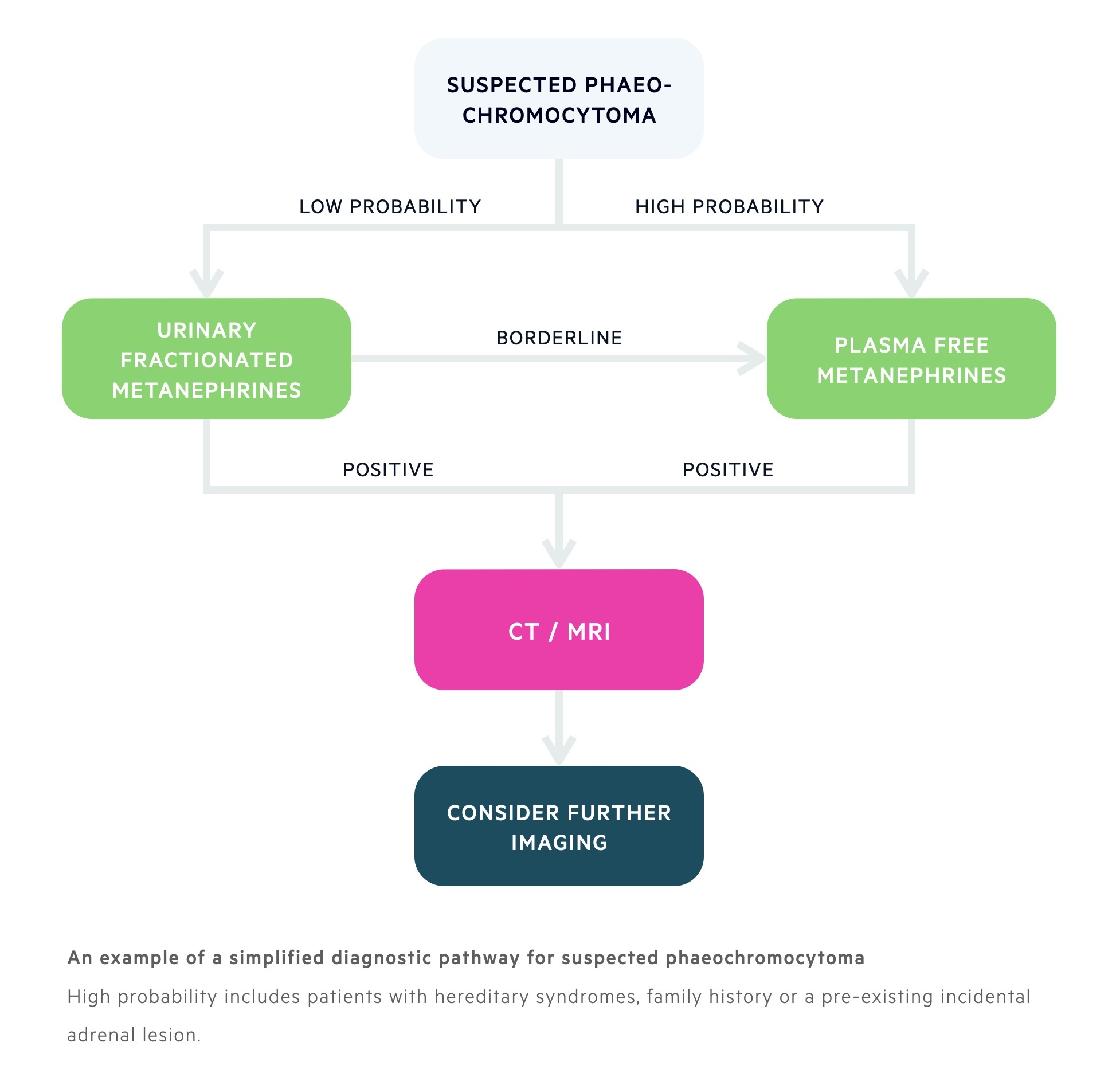

Initial investigations involve identification of elevated metanephrines and/or catecholamines.

Metanephrines are a metabolite of adrenaline that may be measured in the urine or plasma. The choice between measuring plasma levels or urine levels depends on the centre and pre-test probability. Urinary measurements are generally used for low risk patients and plasma measurements for those at high-risk.

Urinary fractionated metanephrines

A 24-hour urinary collection for urinary metanephrines is an appropriate investigation for those with possible sporadic disease based on clinical suspicion. It may be completed twice on non-consecutive days.

Plasma free metanephrines

Patients considered high risk of phaeochromocytoma can have plasma levels of metanephrines. This is usually reserved for patients with a personal or family history of phaeochromocytoma, known genetic syndrome or suspected adenoma on imaging.

Plasma metanephrines and catecholamines have a high negative predictive value. This means patients without raised levels are high unlikely to have a phaechromocytoma. However, it does result in false positives. As such, to prevent unnecessary investigations and potential surgery, the test is reserved for high risk patients.

Radiological investigations

Following confirmation of elevated catecholamines, radiological investigations are used to locate the tumour.

As discussed, ~95% of tumours are found in the abdomen and pelvis. Therefore, cross-sectional imaging usually focuses on these areas in the initial work-up.

Imaging should generally only follow suggestive biochemical testing. Of course an incidental finding on imaging may have prompted investigations in the first place.

Cross-sectional imaging

Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis can both be completed as part of initial radiological investigations.

Both imaging modalities are highly sensitive (up to 100%) but only 70% specific due to the high rate of incidentalomas. An incidentaloma refers to an adrenal lesion >1 cm that is discovered incidentally on imaging. The problem with these lesions is that it is unclear whether they are malignant, functioning or the cause of symptoms. Further tests are usually required.

Additional imaging

In patients with negative CT/MRI (and phaeochromocytoma still suspected) or those with suspected extra-adrenal disease / metastatic spread, further imaging may be arranged.

Options can include:

- Metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scintigraphy: MIBG resembles noradrenaline and is taken up by adrenergic tissue. Typically used to where CT/MRI does not show a causative lesion, to confirm avidity of the primary lesion or patients with suspected metastatic disease or recurrent disease.

- Fludeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET): able to evaluate metabolic activity by measuring accumulation of the radioactive fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), which is an analogue of glucose, that is taken up by tumours. Typically used to distinguish benign and malignant tumours.

Management

The definitive management of a phaeochromocytoma is surgical resection following medical optimisation.

Prior to surgery, it is important to optimise blood pressure control due to the risk of hypertensive crisis from anaesthesia and/or surgical manipulation.

Bloods pressure control

The most effective method to control blood pressure is combined alpha and beta-adrenergic blockade. Beta-blockers should never be used as single therapy as it can precipitate hypertensive crisis from unopposed alpha-adrenergic stimulation. This is because peripheral beta-receptors have a vasodilatory effect.

Options:

- Alpha-blockers: traditionally phenoxybenzamine (irreversible, long-acting, alpha-blocker) is preferred for pre-operative blood pressure control. Other alpha-blockers may be used including prazosin or doxazosin.

- Beta-blockers: introduced only once adequate alpha-blockade has been achieved. Options may include propranolol or metoprolol.

- Calcium-channel blockers: can be used as an alternative to alpha blockers (e.g. amlodipine). May be used to supplement blood pressure control if inadequate response on both alpha and beta-blockade.

- Metyrosine: inhibits catecholamine synthesis. Usually only used in patients who cannot tolerate alpha and beta-blockade. Associated with many side-effects (e.g. depression, anxiety, nightmares).

Volume expansion

Patients are encouraged to have a high sodium diet due to the volume loss with excessive catecholamines and increased risk of orthostatic hypotension with alpha-blockers.

Surgical resection

Adrenalectomy is the surgery of choice in phaeochromocytoma, this can be completed laparoscopically or open depending on patient factors and local expertise.

In sporadic cases the whole gland may be removed. In hereditary cases, due to the risk of bilateral involvement partial adrenalectomy should be considered. If both adrenal glands need to be removed, without cortical-sparing techniques, patients will require lifelong glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement.

Paragangliomas may require special approaches depending on the location of the tumour.

Additional therapies

There are limited therapeutic options for patients with metastatic phaeochromocytoma. Options may include surgical resection combined with radioactive therapy (e.g. radioactive iodine attached to MIBG) that is taken up by adrenal tissue.

Complications

Cardiac complications include hypertension, cardiomyopathy and arrhythmias.

- Cardiac: cardiomyopathy, cardiac arrhythmias, hypertension

- Metabolic: Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- Neurological: stroke, seizure, cerebral haemorrhage (usually from hypertensive crisis)

- Post-surgical: recurrent disease, adrenal insufficiency (if bilateral resection)

Last updated: May 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback