COVID-19

Notes

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 is a respiratory disease caused by the virus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) emerged in 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province in China. On 8th December 2019, there were initial reports of an unusual pneumonia which following investigation was reported to the World Health Organisation (WHO) by the Chinese authorities on 31st December 2019.

By January 2020, the causative organism of COVID-19 was identified as a novel coronavirus and termed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Unfortunately, the virus spread significantly throughout the world and was declared a pandemic on 11th March 2020. As of November 2021, there have been an estimated 254 million cases and 5.11 million deaths globally.

The assessment and management of COVID-19 is an area of great ongoing change and development. These notes aim to give a general overview of the disease and current treatments.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of COVID-19 is changing rapidly with significant geographical differences.

There is a wealth of up to date information available that is tracking the rapidly changing epidemiology of the COVID-19 pandemic. Three excellent resources are the WHO, Johns Hopkins University and the UK government.

- WHO: provide weekly updates on the emerging epidemiology of COVID-19

- Johns Hopkins University: interactive map and up to date tracker on the number of COVID-19 cases and burden of the disease worldwide

- UK Government: excellent website on current COVID-19 statistics within the UK

Coronaviruses

Coronaviruses are a family of positive strand RNA viruses.

Coronaviruses are common pathogens that can infect a range of mammals (including humans) and birds.

Classification

SARS-CoV-2 is part of a wider family of coronaviruses, a group of related RNA viruses. This family of cororonaviruses are further divided into the subfamily Orthocoronavirinae, which is again divided into four genera known as alpha, beta, gamma, and delta.

In humans, coronaviruses commonly cause respiratory tract infections that range in severity from mild to lethal. These human coronaviruses (HCoV) belong to either the alpha or beta genera.

- Human alpha coronaviruses: HCoV-229E and HCoV-NL63

- Human beta coronaviruses: HCoV-HKU1, HCoV-OC43, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), SARS-CoV-1, and SARS-CoV-2

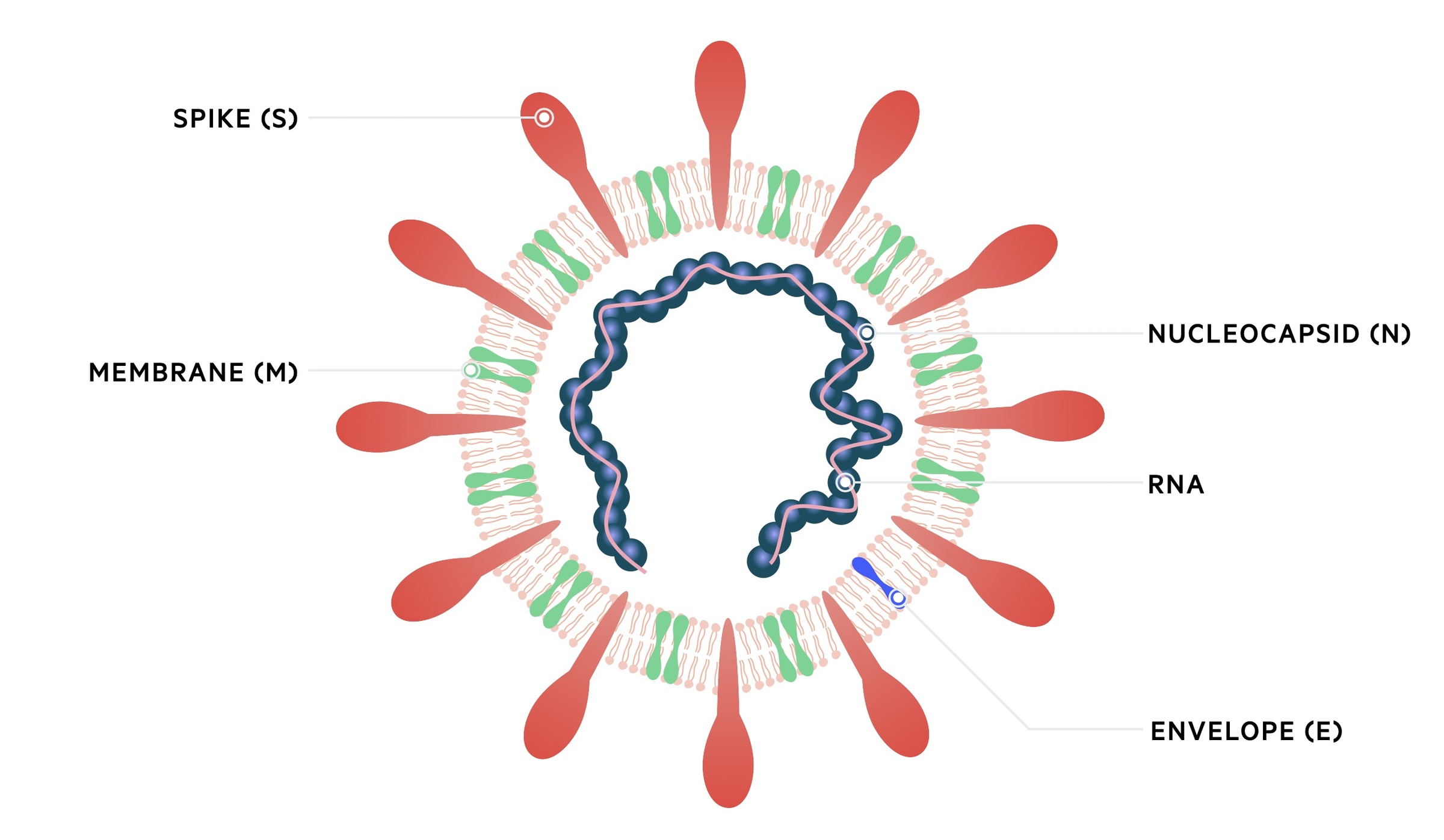

Structure

Coronaviruses are enveloped, positive-stranded RNA viruses. The terminology ‘positive’ or ‘negative' strand essentially refers to the similarity to mRNA:

- Positive-stranded RNA: viral RNA can be translated directly into proteins. The viral genome is essentially mRNA.

- Negative-stranded RNA: viral RNA is complementary to mRNA. It requires synthesis into the positive strand before translation into proteins

Coronaviruses have a very large viral genome (27-32 kb), which encodes four or five structural proteins known as S, M, N, E and HE. They form roughly spherical particles 50-200 nm in diameter

- Spike protein (S): projects from the viral envelope. Mediates receptor binding and cell entry

- Membrane protein (M): involved in viral assembly

- Nucleocapsid protein (N): forms the nucleocapsid that’s holds the RNA genome

- Small envelope (E): thought to be involved in virus assembly

- Hemagglutinin-esterase glycoprotein (HE): only found in some non-SARS beta coronaviruses. Involved in cell binding

SARS-CoV-2

SARS-CoV-2 is the cause of the global contagious respiratory disease COVID-19.

The term ‘SARS’ known as severe acute respiratory syndrome was initially coined in 2003 by WHO following an outbreak of a rapidly progressive respiratory illness that was identified to be caused by a novel coronavirus.

Following identification of another novel coronavirus as the cause of COVID-19, genetic analysis showed it was a beta coronavirus in the same subgenus as SARS, now known as SARS-CoV-1. This led to it being termed SARS-CoV-2, which showed RNA sequence similarity to two coronaviruses that infect bats. These animals are postulated as the origin of the virus, although whether an intermediate host was involved in transmission to humans is unclear.

Structure

SARS-CoV-2 is structurally similar to other coronaviruses with an RNA genome that encodes four structural proteins known as S, M, N and E. The virus is able to gain entry into the host by binding to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptors on human cells via its Spike protein (S).

Variants

Thousands of variants of SARS-CoV-2 have emerged due to viral mutations. Most of these mutations have no effect on viral function. However, several variants have enabled greater transmission and lethality.

Major variants of concern include:

- Delta variant: first identified in India December 2020. Highly transmissible.

- Omicron variant: first reported in South Africa November 2021. Multiple mutations in spike protein. Increased transmissibility and reduced susceptibility to antibodies

- Alpha variant: first identified in UK late 2020. Was 50-75 percent more transmissible than previous strains. Declined with emergence of delta variant.

Other significant variants have been identified across the globe.

Transmission

The primary means of transmission is direct person-to-person respiratory transmission.

COVID-19 is primarily a respiratory disease that is transmitted from direct person-to-person transmission. This occurs due to close contact (i.e. within two metres or six feet) via respiratory particles.

Respiratory particles

Respiratory particles may be transmitted via respiratory secretions or saliva that are inhaled or make contact with mucous membranes (e.g. eyes, nose, mouth). Respiratory secretions and saliva may be spread by:

- Coughing

- Sneezing

- Talking

- Contamination of hands

- Contamination of surfaces

Other methods of transmission

Several other methods of transmission have been recognised but these are less well established. These methods include:

- Airborne: refers to respiratory particles that can remain in the air over greater time and distance (e.g. from aerosol generating procedures such as intubation).

- Non-respiratory secretions: examples include stool, blood, ocular secretions and semen.

Infectivity

The incubation period of COVID-19 is generally 4-6 days (median 5), but can be as long as 14 days. The incubation period describes the time from exposure to onset of symptoms. During this ‘pre-symptomatic’ period, patients can be contagious and transmit the virus to other individuals.

Infectivity generally begins 2-3 days before symptom onset and patients are more likely to be contagious during the early stages of illness when viral RNA levels are highest.

The risk of transmission depends on the closeness between the infected person and other individuals as well as the duration of contact. The risk is highest during prolonged indoor contact. Furthermore, risk of transmission appears to be less if the infected person is asymptomatic compared to one who is symptomatic.

Risk factors

There are well recognised risk factors that increase the risk of severe illness and death.

The predominant risk factors that increase a patients risk of having a severe illness include age and co-morbidities. A list of risk factors are discussed below:

- Age: older patients have a higher mortality

- Sex: male patients are at increased risk

- Co-morbidity: several conditions are associated with a more severe outcome including cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, chronic lung disease, chronic kidney disease, obesity, malignancy and smoking

- Ethnicity: In the UK, people of Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, Other Asian, Caribbean, and Other Black ethnicity have an increased risk of severe illness compared to white British people

- Laboratory features: several laboratory features (e.g. elevated d-dimer, elevated LDH) are associated with an adverse outcome

Pathophysiology

The angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor has been identified as the binding site for SAR-CoV-2.

Replication

Following transmission, coronavirus particles target the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor (ACE-2r) on cells of the upper and lower airways, namely nasal and bronchial epithelial cells and pneumocytes. Binding between ACE-2r and coronavirus particles is mediated by the spike protein.

Following binding, a host protein known as type 2 transmembrane serine protease (TMPRSS2) promotes viral uptake through activation of the spike protein. One inside the host cell, the particle releases viral RNA and undergoes replication using RNA polymerase. Viral proteins are translated from RNA and they are integrated into the host endoplasmic reticulum, which is facilitated by the M protein. From here, the nucleocapsid is formed and they are transmitted to the plasma membrane via golgi vesicles. They then undergo exocytosis taking some of the host cell membrane to form the viral envelope of the new coronavirus particle, which can then infect adjacent cells.

Pathogenesis

The initial binding and replication within the airways continues for a couple of days before an immune response is generated. The patient may still be asymptomatic during this early stage. The virus then propagates further down the respiratory tract to involve the upper airways, which prompts development of typical symptoms of cough, fever and malaise.

This leads to a more pronounced immune response with release of inflammatory cytokines (e.g. CXCL-10, IFN-beta, IFN-gamma) and migration of immune cells (e.g. lymphocytes). The coronavirus particles are able to infect and kill T lymphocytes leading to the classic lymphopaenia seen in laboratory testing as well as disrupt the normal immune response. However, the majority of patients are enable to mount a sufficient response to clear the virus at this stage.

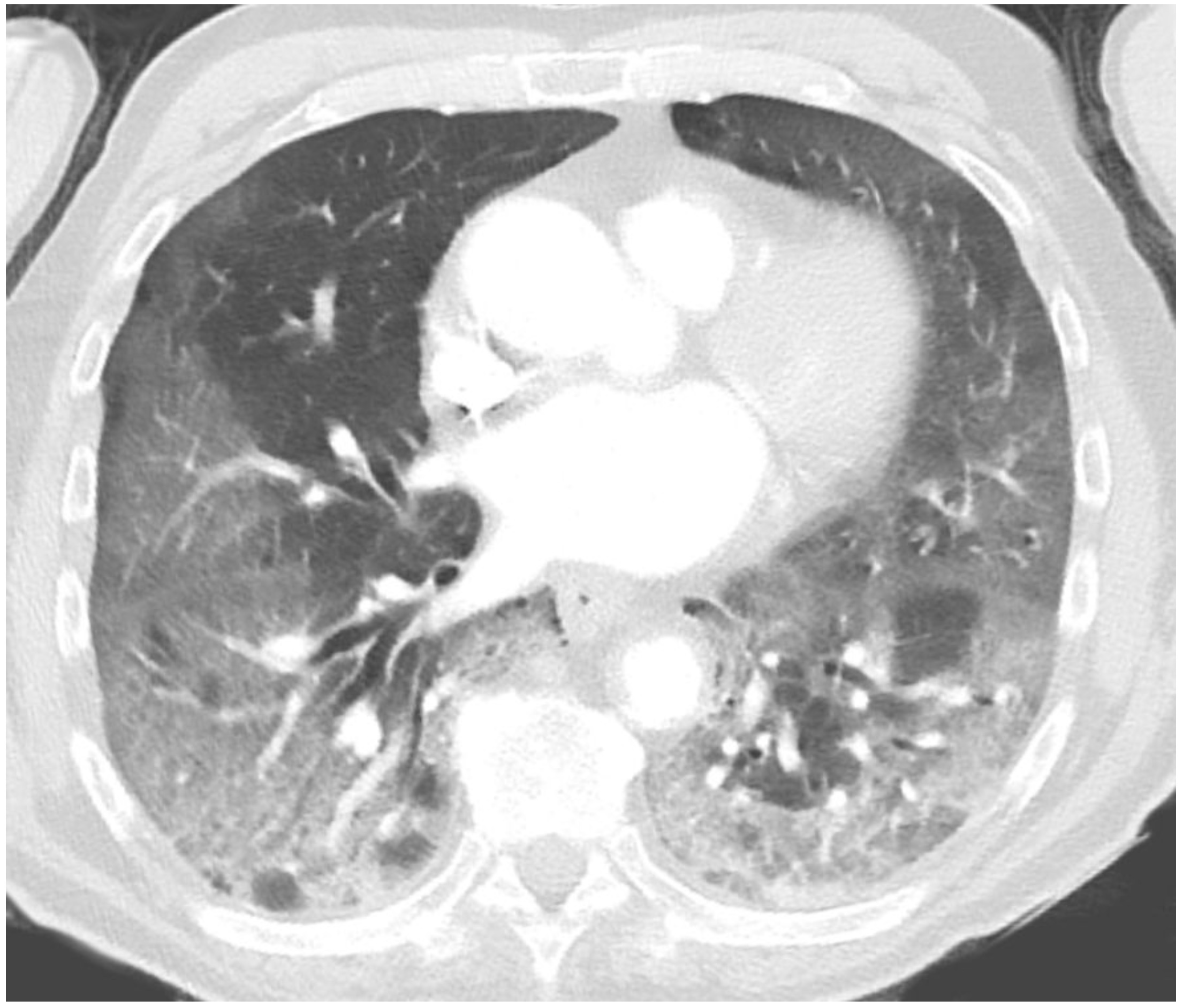

In approximately 1/5th of patients, there is progressive disease with coronavirus particles infecting type II pneumocytes in the lower airways. This promotes a much stronger immune response with release of many pro inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-1, IL-6, TNF-alpha). This causes chemoattraction of white blood cells to the lungs where they initiate a profound immune response. In an attempt to clear the virus there is significant lung injury. With the increasing destruction of pneumocytes there is diffuse alveolar damage that can lead to adult respiratory distress syndrome. This can be life-threatening leading to severe respiratory failure and multi-organ failure. On imaging, this inflammation can be seen as widespread white infiltrates on chest x-ray and ground-glass opacities on CT.

Procoagulant effect

The exaggerated immune response developing in severe COVID can promote widespread activation of the coagulation system leading to development of microthrombi and a high incidence of venous thromboembolisms including pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, and arterial thrombosis (e.g. stroke, ischaemia limb).

Clinical features

A significant proportion of patients with COVID-19 remain asymptomatic.

There are a wide range of clinical features in COVID-19. The incubation period is estimated to occur within 14 days (median 5), but the vast majority will show symptoms within 10 days. As high as 40% of patients may be asymptomatic.

Early infection

The majority of symptomatic patients experience fever, cough, fatigue and shortness of breath.

- Fever

- Cough

- Fatigue

- Dyspnoea

- Anorexia

- Myalgia

- Anosmia

- Cutaneous rash: maculopapular, petechial, urticaria

- Other non-specific symptoms: diarrhoea, abdominal pain, nausea, headache, dizziness, sore throat, loss of taste (ageusia)

NOTE: gastrointestinal symptoms may be the presenting complaint in some patients (e.g. abdominal pain, diarrhoea).

Evolving infection

Over the course of 7-10 days, patients may develop worsening symptoms with progressive shortness of breath and hypoxia on testing. Development of dyspnoea occurs over a median of 5 days with hospital admission occuring at day 7 (on average) from symptom onset.

- All early infection symptoms (as above)

- Worsening dyspnoea

- Tachypnoea (> 30 breath per minute)

- Hypoxia (<90% on room air)

- Signs of organ dysfunction: altered mental status, reduced urine output, hypotension, cool extremities, mottled skin

Inflammatory manifestations

Numerous organ-specific complications may occur in COVID-19 due to the profound inflammatory response to the virus.

- Respiratory: acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Cardiac: myocarditis, arrhythmias

- Coagulation: venous and arterial thromboembolism

- Neurological: encephalopathy, seizures, stroke, neuropathies

- Miscellaneous: Kawasaki-like illness in children

Long-term sequelae

A proportion of patients may take significant time to recover from COVID-19, which can last several months and even longer. Symptoms such as fatigue, dyspnea and cough may persist. This clinical picture is often referred to as ‘long COVID’.

Clinical severity

The severity of illness from COVID-19 is very broad and divided into mild, moderate, severe and critical.

The severity of COVID-19 can be based on classification in NICE 191: Managing COVID-19.

Mild

Refers to evidence of COVID-19 without evidence of viral pneumonia or hypoxia. Clinical features are consistent with early infection. Older people or those who are immunosuppressed may have atypical presentations.

Moderate

Consistent with viral pneumonia. Typical features of pneumonia include fever, cough, and tachypnoea. May see typical changes of COVID-19 on imaging. No signs of severe pneumonia (sats ≥90% on room air).

Severe

Consistent with severe pneumonia. Characterised by typical clinical features with severe tachypnoea (>30 breaths per minute), hypoxia (<90% on room air) or severe respiratory distress.

Critical

Patients with critical disease may fall into one of several different types:

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): this is a type of respiratory failure that is characterised by bilateral infiltrates on imaging and cannot be explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload (i.e. non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema).

- Sepsis: characterised by acute life-threatening organ dysfunction due to an exaggerated inflammatory response. Typical signs of organ dysfunction include altered mental status, hypoxia, reduce urine output, hypotension, thrombocytopaenia, coagulopathy, high lactate (hypoperfusion) and hyperbilirubinaemia.

- Septic shock: this describes persistent hypotension despite resuscitation with intravenous fluids. Medications called vasopressors are needed to improve blood pressure and peripheral perfusion.

Diagnosis & investigations

Diagnosis of COVID-19 is based on nucleic acid amplification testing to detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA.

COVID-19 is usually diagnosed based on identification of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA from a respiratory sample. This is typically obtained from a nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab.

Nucleic acid amplification testing

Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) is a way of amplifying genetic material to detect levels of the viral RNA. It is used for may different pathogens. The most common method is by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR).

A patient who has a positive swab for SARS-CoV-2 RNA is diagnosed with COVID-19. There are some issues with false negative results (i.e. a patient who has COVID-19 based on clinical symptoms or imaging but is swab negative). Hospitals have local guidelines for these situations.

Lateral flow testing

These are easy to use tests that can deliver a result within 30 minutes. A sample (e.g. nasopharyngeal swab) is mixed with solution and applied to the testing area. SARS-CoV-2 antigens are detected by specific antibodies bound to the test line that results in a colour change.

Lateral flow devices are less sensitive than the standard PCR tests.

Antibody testing

The detection of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in the serum of patients is known as serological testing. These types of tests are unlikely to be positive in early infection until an immune response has been generated. This means they are not useful in the acute setting.

Antibody testing can be used to determine previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and formation of an immune response. However, it is unclear whether this confers long-term immunity. The duration of detectable antibodies also varies depending on the initial antibody response and severity of illness.

Investigations

Investigations are crucial to determine the severity of illness in patients presenting to hospital.

Bedside

- Oxygen saturations: pulse oximetry

- ECG: at risk of cardiac arrhythmias

- Blood glucose

- Nasopharyngeal swab: PCR for COVID-19

- Sputum culture: if concurrent bacterial infection suspected

Bloods

- Arterial blood gas (ABG): recommend if significant hypoxia or concern about type 2 respiratory failure

- Venous blood gas (VBG): if decision not to undertake ABG

- Blood cultures: to exclude bacterial infection

- FBC: classically shows lymphopaenia. Low platelets may be feature of severe disease

- U&E: risk of acute kidney injury

- LFTs: may be deranged in severe illness

- CRP: typically elevated

- D-dimer: high levels associated with severe disease

- Procalcitonin (PCT): biomarker specific to bacterial infection. May be used to guide antibiotics (e.g. concurrent bacterial infection)

- Coagulation: deranged clotting associated with severe disease

- Troponin: elevated levels may indicate myocardial injury. Important to exclude ACS.

- LDH: typically elevated

Imaging

- Chest x-ray: may be normal in mild or early disease. As disease progresses, associated with bilateral infiltrates, which are seen as white opacification (ground-glass changes) predominately in lower distribution but may extend to all lung fields.

- CT chest: may be used to exclude PE (pulmonary angiography), secondary complications or when the diagnosis is unclear. Typical features of viral pneumonia are seen on CT including ground-glass opacification with or without consolidation. Distribution is similar to that on chest x-ray with bilateral, lower zone involvement.

Typical bilateral infiltrates on x-ray secondary to COVID-19

Image courtesy of Hellerhoff (Wikimedia commons)

Typical lung changes on CT secondary to COVID-19

Image courtesy of Hellerhoff (Wikimedia commons)

Special

Further investigations depend on the clinical context and suspected complications. These may include:

- ECHO: suspected myocardial infarction or myocarditis

- CT head: if worsening confusion or lateralising neurological signs

- US doppler: if DVT suspected

Management principles

Treatment of COVID-19 is mainly conservative unless patients have severe disease requiring hospital admission.

NICE have recently published an excellent ‘rapid guideline’ (NG191) on the management of patients with COVID-19. This is an excellent summary of the current management strategies for patients with COVID-19.

The UK government has also published numerous articles on the prevention of spread and management of COVID-19 in a non-clinical setting. This includes how to prevent spread of COVID-19, current government guidelines on social mixing and social distancing rules.

The basic principles of management include:

- Maintain social distancing rules including shielding where appropriate

- Follow government advice on social mixing, work and leisure activities

- Maintain excellent basic hygiene (e.g. hand washing, avoid touching face, cleaning or disinfecting objects)

- Wear a mask where appropriate or mandatory

- Follow self-isolation rules if symptomatic or have confirmed COVID-19

Current NHS advice on self-isolation is available at the NHS website.

Conservative management

The majority of patients with COVID-19 will not require hospital admission.

Approximately 80% of patients with COVID-19 will have a mild illness that does not require medical intervention or admission to hospital. The following basic measures can be given to most patients:

- Self-isolation: Follow self-isolation rules in line with NHS guidance

- Seek help: Advice to seek medical advice (e.g. NHS 111) if worsening symptoms

- Dehydration: Avoid dehydration and increase fluid intake

- Fever: Take simple antipyretics to manage fever if no contraindications (paracetamol or ibuprofen)

- Monitoring: it may be appropriate to monitor symptoms and oxygen saturations using pulse oximetry. Local hospital guideline and protocols are available

Pharmacological management

Numerous pharmacological agents are now used in the management of COVID-19 among patients admitted to hospital.

Since the outbreak of the pandemic in March 2020, numerous medications have been trialed for the treatment of COVID-19. Randomised controlled trials are still ongoing to determine the most effective treatments and this will be a changing landscape. The NICE rapid COVID guidelines outline recommendations for the current pharmacological agents.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not used in the treatment of COVID-19. They may be used if there is a strong clinical suspicion of a secondary bacterial infection.

Corticosteroids

Patients should be offered dexamethasone (hydrocortisone or prednisolone if dexamethasone is unavailable) in the following situations:

- Require supplemental oxygen to meet saturation targets

- Hypoxia requiring supplemental oxygen but unable to have or tolerate it

Dexamethasone is recommended at 6 mg (PO/IV) daily for up to 10 days. Treatment should be stopped if discharged from the hospital or a supervised virtual COVID ward. Co-prescription with a PPI should be considered and close monitoring of blood glucose is required. This is because of the risk of gastric ulceration and steroid-induced hyperglycaemia, respectively.

Casirivimab and imdevimab

Monoclonal antibodies that specifically target the spike protein. This blocks cellular entry.

Advised in patients ≥12 years old who are hospitalised with COVID-19 and have no SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

Remdesivir

Remdesivir is an anti-viral agent that works through the inhibition of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. It may be considered for up to 5 days for COVID-19 pneumonia in adults who need low-flow supplemental oxygen.

Tocilizumab

Tocilizumab is a monoclonal antibody directed against the IL-6 receptor blocking the binding of IL-6. The use of tocilizumab has been shown to improve survival among patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19. There are a number of specified criteria to meet to warrant prescription and administration. Sarilumab is another monoclonal antibody directed against the IL-6 receptor that can be used as treatment.

Anticoagulation

The procoagulant effects of COVID-19 is well recognised. Consequently, several trials have looked at the benefit of administrating treatment dose anticoagulation. Current recommendations include (assuming no contraindications to anticoagulation):

- Prescribe a standard prophylactic dose of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) to patients requiring oxygen for a minimum of 7 days (even after discharge).

- Consider prescribing treatment dose LMWH to patients who need low flow oxygen for 14 days (or until discharged).

Respiratory support

Patients with COVID-19 can develop progressive respiratory failure requiring increasing levels of respiratory support.

Patients with severe COVID-19 are hypoxic and oxygen is the principle treatment. The amount of oxygen that can be delivered depends on the device. As the disease progresses patient may require positive pressure ventilation (non-invasive or invasive) to help maintain airway opening and adequate ventilation.

Oxygen

Oxygen should be used to maintain a patients saturations in the target range. This should be 94-98% or 88-92% in patients at risk of type 2 respiratory failure. Over the course of the pandemic alteration to global saturation targets have been made at local and regional levels based on evidence, resources and guidelines. Always follow local hospital guidelines.

Different devices can be used to maintain oxygen saturations.

- Nasal cannula (>4 litres is uncomfortable for patients)

- Oxygen delivered (%): 24-44%

- Variable oxygen concentration: affected by respiratory rate and amount delivered via nose.

- Flow rate (L/min): 1-6 litres

- Venturi mask:

- Oxygen delivered (%): 24-60%

- Fixed oxygen concentration: designed to entrain a set amount of oxygen and air giving a fixed concentration

- Flow rate (L/min): coloured coded (2-3 Blue / 4-6 White / 8-12 Yellow / 10-15 Red / 12-15 Green)

- Simple face mask

- Oxygen delivered (%): 30-60%

- Variable oxygen concentration: affected by respiratory rate

- Flow rate (L/min): 6-10 litres

- Non-rebreathe mask (a reservoir bag is connected to the mask with a one-way flap valve)

- Oxygen delivered (%): ~60-85%

- Variable oxygen delivery: affected by respiratory rate

- Flow rate (L/min): 10-15 litres (if lower rates used the reservoir bag can deflate during inspiration)

- Humidifed oxygen

- May be required for flow rates >4L/min due to upper airway dryness and discomfort

- A humidifier attachment can be added to some devices

Non-invasive ventilation

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) is a way of supporting ventilation without having to undergo invasive tracheal intubation. NIV is indicated if high inspired oxygen concentrations (>60%) are not sufficient to maintain adequate oxygenation in patients with respiratory failure (e.g. COVID-19 pneumonia).

There are several methods of delivering NIV:

- High-flow nasal cannula oxygen (HFNC): often referred to as ‘Optiflow’. Provides a high concentration of oxygen (up to 80%) and high flow rate (up to 70 L/min). Provides a small amount of positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP - 2-5 cmH20). This essentially helps to recruit alveoli and prevent collapse.

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP): similar to HFNC, CPAP provides a high concentration of oxygen (up to 80%) and high flow rate (up to 70 L/min). It provides a higher amount of PEEP (up to 10 cmH20), which prevents airway collapse, improves alveoli recruitment and improves ventilation/perfusion matching.

- Bi-level Positive Airway Pressure (BiPAP): this provides air pressure during both inspiration and expiration. The expiratory positive airway pressure (ePAP) is similar to PEEP and helps to prevent alveoli collapse and recruit more alveoli for gas exchange. The inspiratory positive airway pressure (iPAP) assists inspiration and is important for ventilation (exchange of gas). The pressure difference between ePAP and iPAP helps increase tidal volume and minute ventilation. BiPAP is usually reserved for patients with, or at risk of, type 2 respiratory failure.

Invasive ventilation

Invasive ventilation is also known as mechanical ventilation. It involves general anaesthesia, invasive tracheal intubation with placement of a tracheal breathing tube, and connection to a mechanical ventilator that does the breathing for the patient. Patients with COVID-19 who worsen despite NIV, or have so severe symptoms they would not tolerate NIV, require invasive ventilation.

ECMO

In very severe cases, patients may require Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), which is essentially an artificial lung. This is a very specialised treatment that involves diverting a patients blood to an artificial oxygenator before being pumped back to the patients body. It is used when mechanical ventilation is not sufficient to maintain adequate oxygenation and there is deemed a reasonable chance of recovery.

Vaccination

Vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 is a crucial tool in the prevention of spread of COVID-19.

In March 2020, the first human clinical trials were underway for the prevention of COVID-19. Since then, several vaccines have been licensed for use.

Currently licensed vaccines in the UK:

- Pfizer/BioNTech: mRNA vaccine. Leads to the expression of full-length spike protein. Given as two intramuscular doses.

- Moderna: mRNA vaccine. Leads to the expression of full-length spike protein. Given as two intramuscular doses.

- Novavax (Nuvaxovid) – Protein-based vaccine.

- Sanofi-GSK – Recombinant protein-based vaccine with an adjuvant (VidPrevtyn Beta).

NOTE: the AstraZeneca vaccine is no longer used in the UK.

Recommendations

The UK’s current recommendations for COVID-19 vaccinations, particularly for the Autumn 2024 booster programme, target groups at higher risk of severe disease. These recommendations are based on guidance from the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI).

Eligible groups for the Autumn 2024 COVID-19 vaccine include:

- Adults aged 65 years and over.

- Residents in care homes for older adults.

- Individuals aged 6 months to 64 years who are in a clinical risk group, such as those with chronic illnesses or compromised immune systems.

- Frontline NHS and social care workers, including those in care homes for older adults.

The vaccine should generally be offered six months after the previous dose to ensure ongoing protection, especially through the winter months. The focus is on protecting those most vulnerable to severe COVID-19 outcomes, with the JCVI emphasizing that vaccination continues to reduce hospitalizations and deaths.

Side-effects

Several common side-effects may occur with the vaccine including a sore arm from the injection, feeling tired, myalgia, headache, nausea/vomiting.

A number of rare, but potentially serious side-effects include:

- Allergic reaction

- Vaccine-induced thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome: reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CSVT) with Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine. For people under 40 without other health conditions, it's preferable for you to have the Pfizer/BioNTech or Moderna vaccine instead.

- Myocarditis and pericarditis (mainly male adolescents and young adults): reported more frequently than expected after mRNA vaccines

- Guillain-Barre syndrome (potential association)

Complications

COVID-19 can be a life-threatening illness associated with significant complications.

Primarily, COVID-19 is a respiratory illness that can lead to progressive respiratory failure and death. It can cause widespread organ dysfunction and abnormal neurological sequelae.

Organ-specific complications

This is not an exhaustive list of the complications associated with COVID.

- Respiratory: respiratory failure

- Cardiac: Myocarditis, arrhythmias, heart failure

- Coagulation: venous and arterial thromboembolism.

- Hepatic: acute liver injury

- Renal: acute kidney injury

- Neurological: seizures, stroke, neuropathies

- Haematological: haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopaenia

- Miscellaneous: cytokine release syndrome, paediatric inflammatory multi-system syndrome

Long-term complications

It is estimated that up to 10% of patient will develop persistent symptoms lasting >4 weeks. This is often collectively termed ‘long COVID’. There are a variety of symptoms that may form part of ‘long COVID’, which include chronic respiratory symptoms (e.g. cough, shortness of breath), cardiovascular symptoms (e.g. chest tightness), protracted loss of smell and taste, severe fatigue and many others.

Prognosis

The mortality associated with COVID-19 is changing as we understand more about the condition and treatments evolve.

Mortality from COVID-19 varies greatly depending on geographical location. Overall, mortality in patients under 65 years old without co-morbidity is rare. There are various ways to determine mortality:

- Infection fatality rate (IFR): defines proportion of deaths among all infected individuals including confirmed, undiagnosed or unreported cases.

- Case fatality rate (CFR): defines total number of deaths reported divided by the total number of detected cases reported. Subject to selection bias as more severe cases likely to be tested.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States gives as estimate for the current IFR based on age (as of 21st March 2021):

- Ages 0-17: 20 per 1,000,000 infections (0.002%)

- Ages 18-49: 500 per 1,000,000 infections (0.05%)

- Ages 50-64: 6000 per 1,000,000 infection (0.6%)

- Ages ≥65: 90,000 per 1,000,000 infection (9%)

Intensive care mortality

In the UK, the intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre has excellent data on the mortality among patients critically ill from COVID-19 requiring intensive care admission. Among patients admitted to ITU between 1st September 2020 to 25th March 2021, the overall 28-day survival was 63% (95% CI: 62.4-63.6). The mortality was much higher among older patients (> 60% for patients aged 80+, compared to < 25% for those aged < 50 years).

Ethnicity

Public Health England (PHE) have reported on the disparity between survival among different ethnic groups. The data varies between studies but overall appears to show those of Black ethnicity are at greater risk of severe disease than those of Asian ethnicity, who themselves are at greater risk of severe disease than those of White ethnicity. A biobank study quoted by PHE found Black ethnic groups had a 3 times and Asian ethnic groups 2 times higher risk of severe COVID-19 compared to White ethnic groups.

There are a number of significant confounders, some of which are unmeasured or difficult to accurately measure in these studies. Further high-quality research is required to both confirm and explain such observed differences.

Last updated: July 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback