Fungal skin infections

Notes

Overview

Fungal skin infections are very common and often affect feet, groin, or scalp.

Fungal skin infections can be a difficult topic to grasp because there is a wide range of fungi that cause skin infections. In addition, naming conventions for fungal skin infections aren’t always intuitive. For example, ringworm isn’t caused by a worm, and 'Tinea' infections are almost always caused by dermatophyte fungi except for tinea versicolor, which is caused by a different type of fungus (a yeast called Malassezia).

In this article, we will focus on the commonest causes of fungal skin infections in patients with a normal immune system. In patients with a compromised immune system, fungi can cause invasive infections (particularly on intensive care units), but invasive fungal infections are beyond the scope of this topic.

Classification

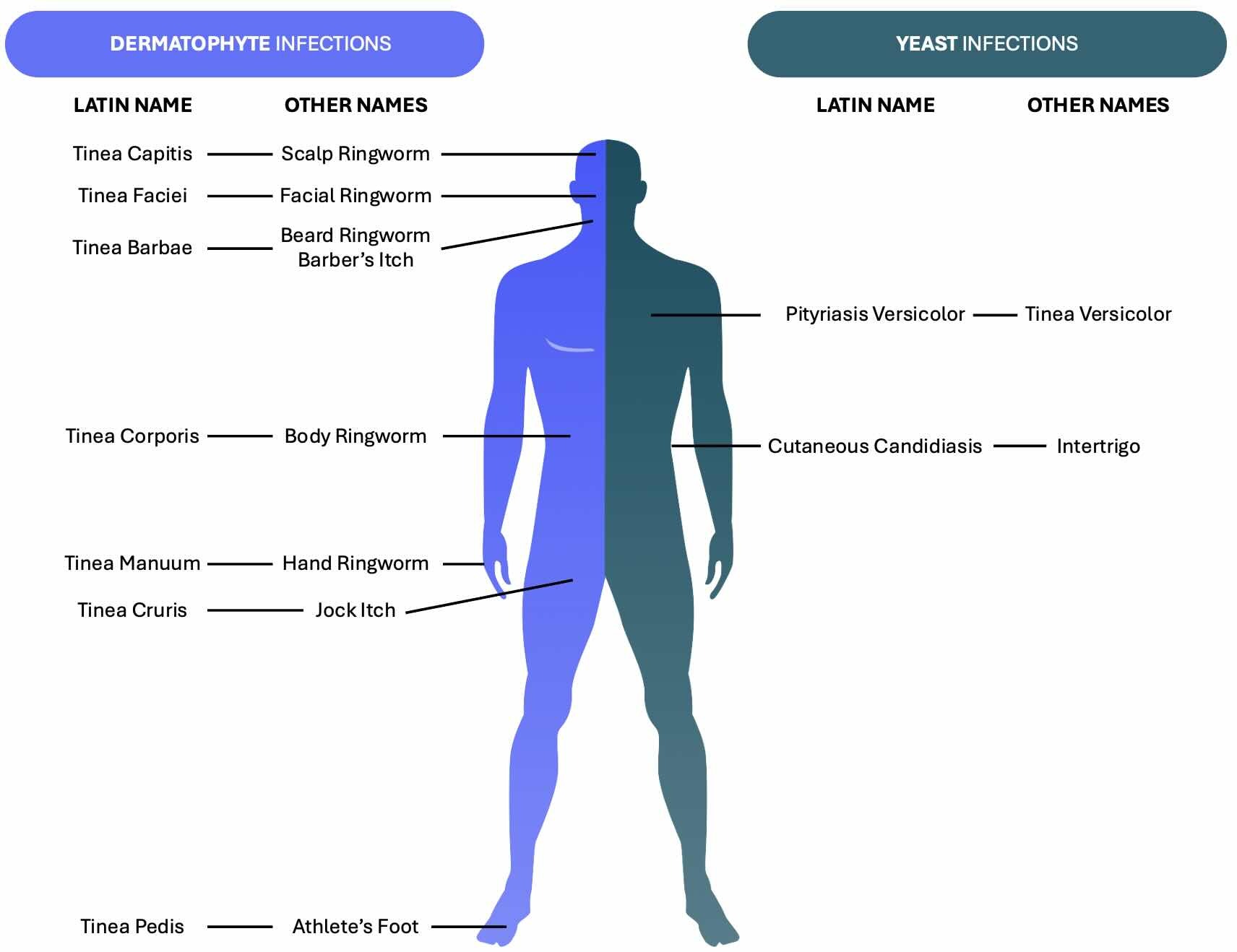

Fungal skin infections may be classified by the infectious organism or the area of the body affected.

To make things as clear as possible, we will classify fungal skin infections in two ways:

- Whether the causative organism is a dermatophyte or a yeast

- Which part of the body is affected.

Definitions

Specific terminology is used for both Dermatophyte infections and yeast infections.

Definitions related to Dermatophyte Infections

“Dermatophyte” –

- A group of closely related fungi, which grow hyphae.

- Survive via the metabolism of keratin in the skin, hair, and nails.

In healthy skin, dermatophyte fungi only grow in the stratum corneum – the outermost layer of dead skin cells – and are prevented from accessing deeper layers of the epidermis by the natural barrier function of the skin. The specific dermatophytes that cause infections in humans are usually of the genera Microsporum and Trichophyton, but don’t worry too much about these names; we usually refer to the infections by the body part that is affected, rather than the specific underlying organism.

“Ringworm” –

- Refers to tinea infections caused by dermatophytes (i.e. all the tinea infections apart from pityriasis versicolor).

- The name comes from the fact that tinea infections (especially tinea corporis) grow in a circular or oval shape.

Definitions related to Yeast Infections

“Yeast” –

- Another group of closely related fungi, which are usually single-celled and reproduce by budding.

- Candida and Malassezia are the genera of yeast that most commonly cause infections in humans.

“Pityriasis” -

- Any of various skin conditions marked by dry scaling patches of skin.

- As used to name Pityriasis Versicolor, a cause of flaking (or scaling) of the skin.

“Versicolor” –

- Literally translates as “changeable in colour”

- Refers to the fact that Pityriasis Versicolor causes colour changes of the skin (causing patches of hypo- or hyper-pigmentation)

Infection naming by body part

- “Capitis” – of the head

- “Faciei” - face

- “Barbae” - bears

- “Corporis” – of the body

- “Manuum” - hand

- “Cruris” – of the leg

- “Pedis” – of the foot

Epidemiology

Fungal skin infections are very common.

The lifetime risk of a fungal infection is 10-20%. Fungal infections tend to be more common in men.

Fungal infections vary by age:

- Tinea capitis usually affects children.

- Tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis usually affect adolescents and young adults.

Aetiology and Pathophysiology

In general, yeast infections result from overgrowth whereas dermatophytes require fungal transmission.

The underlying aetiology and pathophysiology of fungal infections differ depending on the infective organism.

- Dermatophyte infections: require fungal transmission from one host to another i.e. the causative fungus is not usually present on the skin of healthy individuals.

- Yeast infections: result from an overgrowth of a commensal organism which is usually present on the skin or GI tract of healthy individuals.

For the above reasons, dermatophyte infections can be considered contagious, whereas common yeast skin infections are not contagious.

Aetiology

All dermatophytes spread by shedding fungal spores from infected skin. The mechanism of fungal spread tends to vary depending on the site of the underlying infection, and can include the following:

- Direct contact with an infected human

- Direct contact with an infected animal

- Contact with objects or surfaces where fungal spores are present

- Autoinfection (i.e. when dermatophytes are spread from one part of the body to another)

The two main yeasts that cause human infections are Malassezia (causes Pityriasis Versicolor) and Candida (causes cutaneous candidiasis e.g. intertrigo). Less is known about why Malassezia starts to multiply and spread in certain individuals. It is suspected that heat, humidity, and increased sweating might play a role. Candida Albicans is found in the GI tract of 40-60% of healthy adults. Exposure to one or several risk factors (e.g. obesity, skin rubbing) can increase the risk of infection developing.

Risk factors

Fungi like warm, damp conditions. Risk factors for development of a fungal skin infection include:

- Previous or concurrent tinea infection

- Diabetes mellitus

- Immunodeficiency

- Other skin conditions (e.g. Hyperhidrosis)

- Infection of others in the household

- Household crowding

- Wearing occlusive clothing

- Recreational activities involving close contact with others including shared change rooms.

- Skin rubbing on skin (e.g. between skin folds)

- Heat and moisture build-up (e.g. between skin folds)

- Areas of inflammation and maceration

- Obesity

Clinical features

Itching and skin flaking are some cardinal features of a fungal skin infection.

The exact clinical features depend on the infective organism and the location of the infection.

History

Two features are common to all tinea (dermatophyte) infections:

- Itching (pruritis)

- Flaking of the skin

Pityriasis versicolor

- Usually asymptomatic

- Might cause mild itch

Candida

- Usually symptomatic

- Itch

- Pain

Examination

It is important to examine the entire body if you suspect a fungal skin infection. This is because it is not uncommon for fungal infections to spread between different body areas. Your examination should pay close attention to skin, hair, and nails.

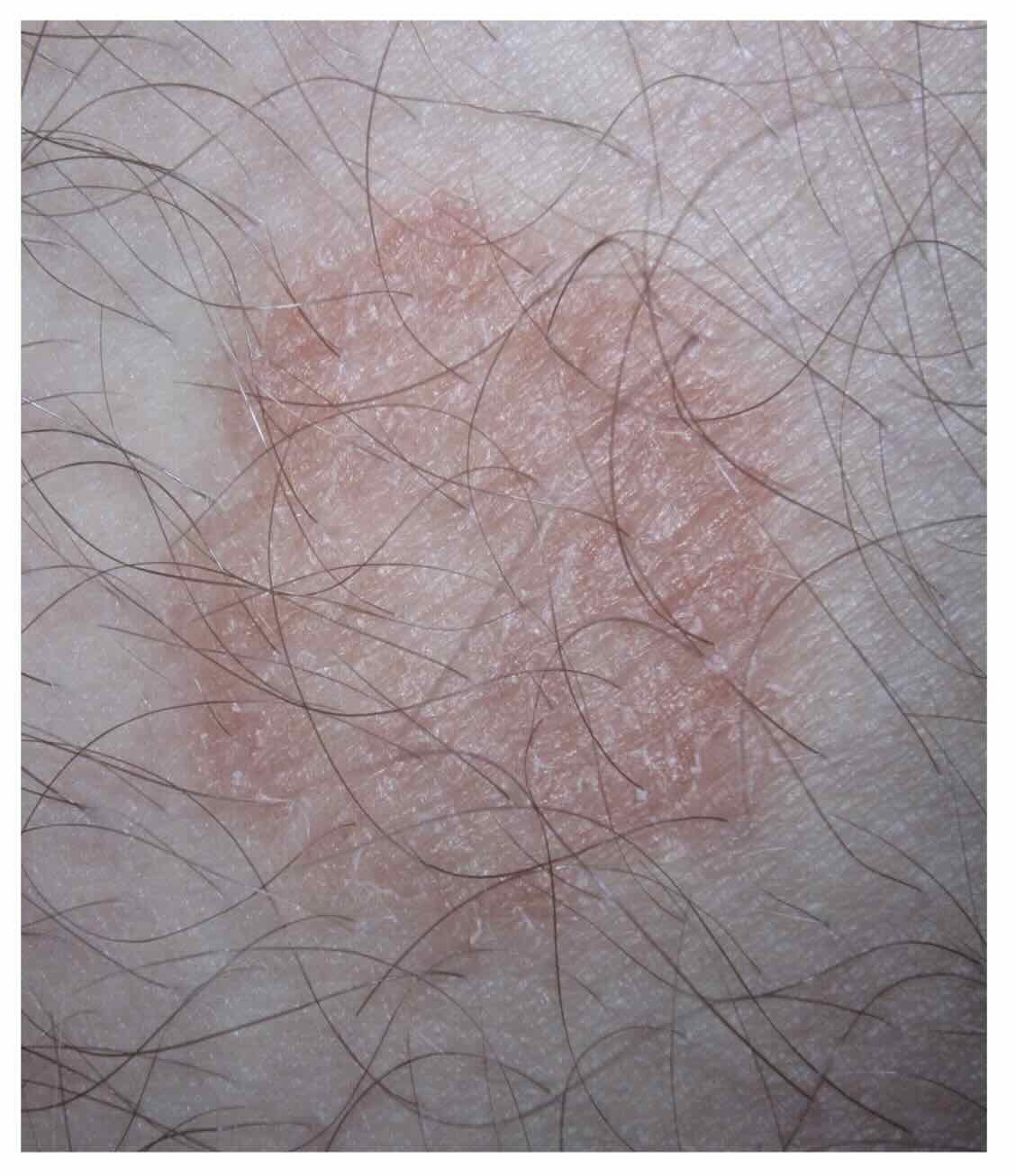

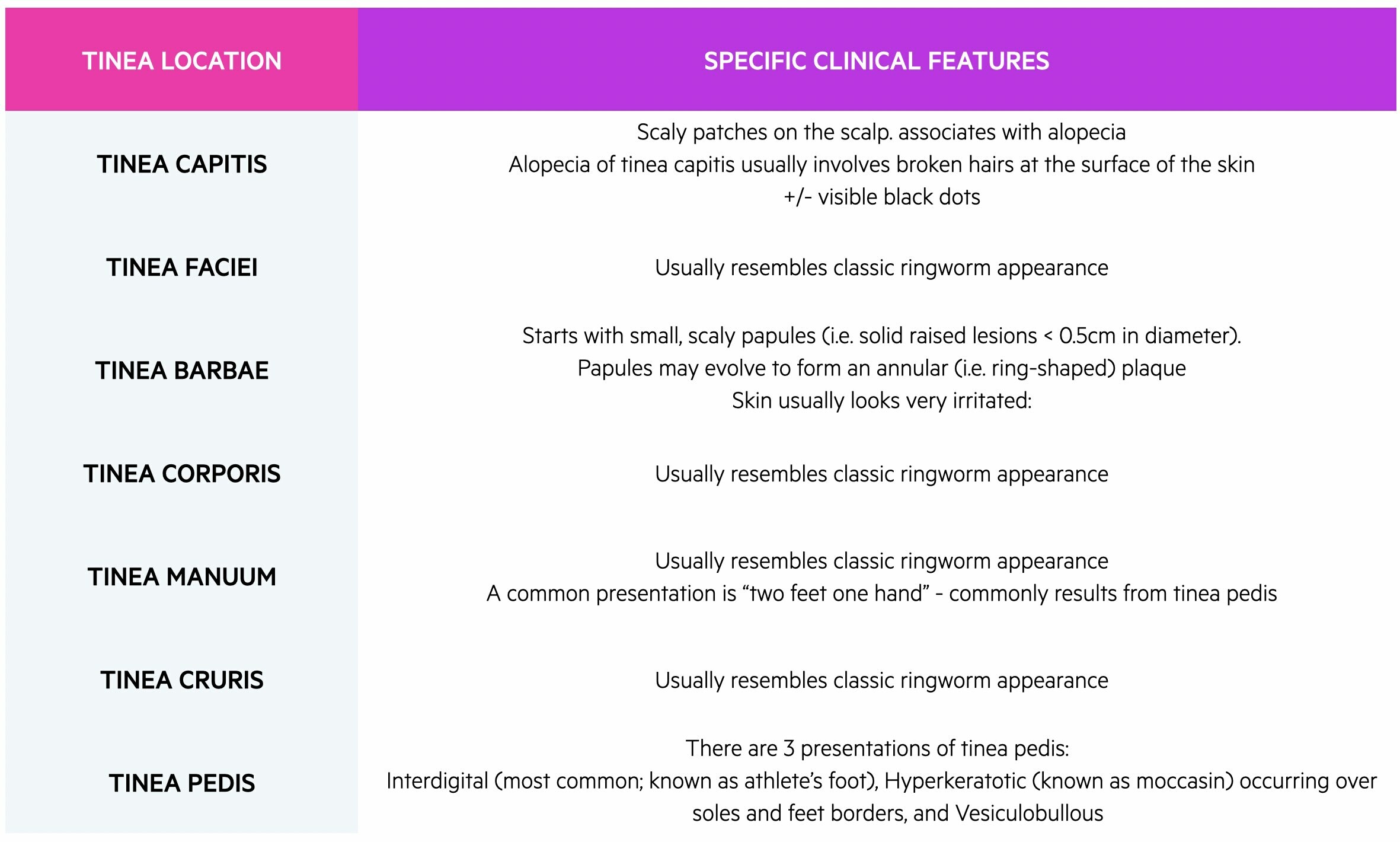

As a general rule (unless otherwise specified in the table below), dermatophyte infections present with the classic “ringworm” lesion, i.e.:

- Circular or oval

- Patch (i.e. a larger flat area of altered colour or texture) OR

- Plaque (i.e. a palpable scaling raised lesion >0.5cm in diameter)

- Usually erythematous

NOTE: The active erythematous/raised border spreads centrifugally, whilst the central part of the lesion undergoes clearing. This leaves a ring-shaped, hence the name ringworm.

Ringworm - Dermatophyte skin infection with mildly raised border and central clearing

(Image courtesy of James Heilam; Wikimedia Commons)

In pityriasis versicolor, pigmentation changes are common and may include hypo- or hyperpigmentation. The colour changes usually begin in small patches but over time, they may increase in size and combine into larger patches. These patches may also become scaly. Skin changes may be difficult to detect in fair-skinned individuals. The patches may only become evident after sunbathing. This is because affected areas will not undergo tanning, whilst the normal surrounding skin will tan. The typical locations of Pityriasis versicolor include:

- Thorax

- Neck

- Upper arms

- Abdomen

- Thighs

Candida is an extremely common infection and leads to several classic examination findings that usually affect the skin folds or flexural areas. These include:

- Erythema

- Pustules

- Maceration

- Fissuring

- Peeling

- Scales

Clinical features by body site

Investigations and diagnosis

NICE Guidelines suggest fungal skin infections should be diagnosed clinically in the majority of cases.

Picking up fungal skin infections when it presents is important. This is because misdiagnosis sometimes results in steroids being prescribed as a monotherapy for the skin changes. Steroid monotherapy is bad news in fungal skin infection – it can cause the infection to spread, and make diagnosing the condition harder in the future. “Tenia incognito” describes the appearance of a dermatophyte skin infection treated inappropriately with steroids.

The examination findings of fungal skin infections can overlap with other skin conditions. With this in mind, NICE recommends sending samples (e.g. skin scrapings) for fungal microscopy and culture if:

- There is severe or extensive disease in adults

- The diagnosis is uncertain or there is an atypical appearance.

Management

As a general rule, topical anti-fungal agents are first-line treatments followed by systemic therapy if they fail or infections are severe.

The management of all fungal skin infections can be split into four categories:

- Conservative

- Medical – topical

- Medical – systemic

- Specialist referral

As a general rule, topical treatments are preferred first-line, with systemic treatments reserved for severe cases, or cases in which topical treatment has failed.

Conservative

Try to avoid the affected area becoming too moist by drying the affected area thoroughly after bathing, showering, or swimming. This includes keeping ‘at risk’ areas such as between the toes and under the breasts clean and dry.

It is vital to try and minimise the spread of fungal spores in the following ways:

- Do not share clothing, sports equipment, or towels.

- Wear slippers or sandals in changing rooms, swimming pools, and showers.

- Wash thoroughly with soap and shampoo after any sport involving skin-to-skin contact.

- Wash clothes, towels, and bed linen frequently.

Medical - topical

Topical treatment is appropriate for mild, non-systemic fungal skin infections. This includes all the dermatophytes and yeasts covered so far in this article

Topical treatment always involves an anti-fungal (e.g. terbinafine or clotrimazole). It’s important to treat all affected body parts at the same time (e.g. both tinea pedis and tina cruris if they co-exist). Otherwise, any remaining fungus acts as a reservoir, which will allow infection to spread again once treatment ends. Topic treatment might include a mildly potent corticosteroid if there is marked skin inflammation.

NOTE: Corticosteroids should never be used as monotherapy (i.e. without an anti-fungal) for fungal skin infections.

Medical - systemic

Systemic treatment is indicated in the presence of:

- Severe disease

- Extensive disease

A positive skin sample for fungal microscopy or culture is desirable in this situation, but if clinical suspicion for fungal infection is high, system antifungals can be started in parallel with sending a skin scraping for fungal microscopy and culture

Terbinafine is the first-line oral antifungal. Be aware that terbinafine can cause hepatotoxicity. It should not be prescribed for patients with liver issues. In all patients, baseline LFTs should be taken, with follow-up LFTs 4-6 weeks after starting treatment. Oral itraconazole is generally the second-line agent.

Specialist Referral

Children with severe or extensive disease should be referred to a paediatric dermatologist.

Specific scenarios

There are some specific scenarios when management diverts away from the general approaches described above. For example, for both Tinea Capitis and Tinea Barbae, systemic anti-fungal treatment is considered first-line. Additionally, for pityriasis versicolor, if only a small area is affected then a topical imidazole cream may be used first-line. If the disease is more widespread, then Ketoconazole 2% shampoo can be used. It should be used once a day as follows: lathered on, left on the affected skin for 3-5 minutes, and then rinsed off thoroughly. It is also important to note that skin colour may take 2-3 months to return to normal and is not an indication of treatment failure.

Complications and prognosis

The prognosis associated with fungal skin infections is usually excellent.

Complications of fungal skin infections include:

- Secondary bacterial infection

- Hair loss (due to tinea capitis)

Scarring is uncommon and the overall prognosis is usually excellent. Important contributors to good prognosis are:

- Compliance with treatment (some treatments must be used for weeks)

- Taking subsequent precautious to avoid repeated infection

Last updated: December 2024

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback