Parkinson's disease

Notes

Overview

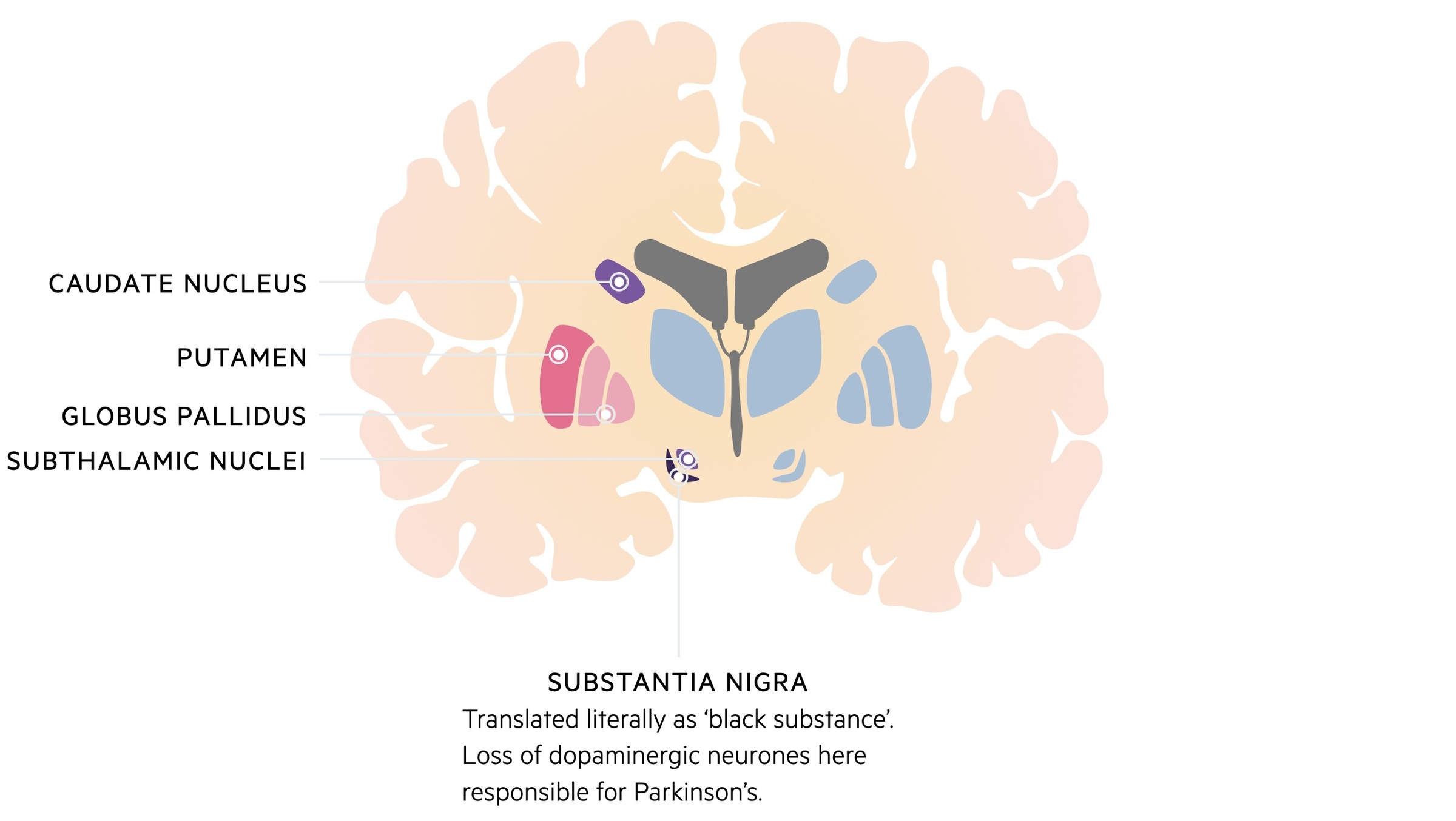

Parkinson’s disease is a chronic, progressive neurodegenerative condition that occurs secondary to loss of dopaminergic neurones within the substantia nigra.

Parkinson’s disease is the most common form of parkinsonism. Parkinsonism describes the presence of bradykinesia and at least one of the following:

- Resting tremor

- Rigidity

- Postural instability

Parkinson’s disease tends to present with unilateral symptoms at onset with gradual progression and the development of bilateral signs. In addition to the motor symptoms, non-motor complications like depression, dementia, sleep disturbance and autonomic dysfunction cause significant ill-health.

Management may consist of medical therapy (e.g. levodopa) and surgical interventions (e.g. deep brain stimulation).

Epidemiology

Parkinson’s disease is one of the most common neurological disorders, it has a lifetime risk of 2.7%.

Parkinson’s disease is slightly more common in men (1.5:1) and the overall prevalence is thought to be increasing, with a projected rise of 27% between 2009 and 2020 in the UK.

The onset of Parkinson’s disease usually peaks between the ages of 55-65 years and generally has a slowly progressive onset.

Anatomy & physiology

The basal ganglia are collections of nuclei found in the subcortical white matter.

Anatomy

The basal ganglia describe a series of cell bodies (i.e. gray matter) that are located together within the deep subcortical white matter of the brain.

The thalamus, though not formally considered part of the basal ganglia, forms extensive connections with the nuclei.

Physiology

The basal ganglia have a number of important roles in movement generation. In simple terms, it helps to kick start and fine tune movement initiated by the motor cortex in a coordinated manner.

Some of the important functions of the basal ganglia include:

- Inhibition of muscle tone

- Coordinated, slow, sustained movement

- Suppression of useless patterns of movement

- Initiation of movement

Aetiology

Parkinson’s disease is a condition of idiopathic aetiology.

It is thought that a small proportion (approx 2-3% ) of cases of Parkinson’s disease can be attributed to a monogenic cause (i.e. a single gene variant causing the disease).

In the majority of cases the aetiology is largely unknown and probably related to a complex interaction between a patients genetics and their environment.

Pathophysiology

Parkinson’s disease may not be apparent until a substantial number of neurones (50-80%) have been lost within the substantia nigra.

The basal ganglia are essential for the modulation of pyramidal motor output to allow normal movement. This process of modulation is dependent on two pathways within the substantia nigra, the direct and indirect pathways.

Direct pathway

The direct pathway is mostly a stimulatory pathway (‘on’ pathway) that is shorter, mostly off and predominantly associated with D1 receptors.

Activation of the direct pathway leads to a series of neural connections through the basal ganglia, which eventually leads to the initiation of movement. Dopamine that is released from the substantia nigra via dopaminergic neurones is able to activate the direct pathway via D1 receptors leading to the generation of movement.

Indirect pathway

The indirect pathway is mostly an inhibitory pathway (‘off’ pathway) that is longer, mostly on and predominantly associated with D2 receptors.

Activation of the indirect pathway is essential in the inhibition of muscular tone to prevent unnecessary movement. Dopamine that is released from the substantia nigra via dopaminergic neurones is able to inhibit the indirect pathway via D2 receptors therefore leading to the generation of movement (i.e. inhibiting the inhibitor)

Summary

Collectively, this shows how the release of dopamine may act on both the direct and indirect pathway to lead to a ‘kick-start’ in movement generation. Importantly, this process is fine-tuned to allow coordinated movement when it is needed by close interaction with the motor cortex via corticonigra fibres.

It is therefore unsurprising that in Parkinson’s disease there is a problem with the initiation of movement.

Clinical features

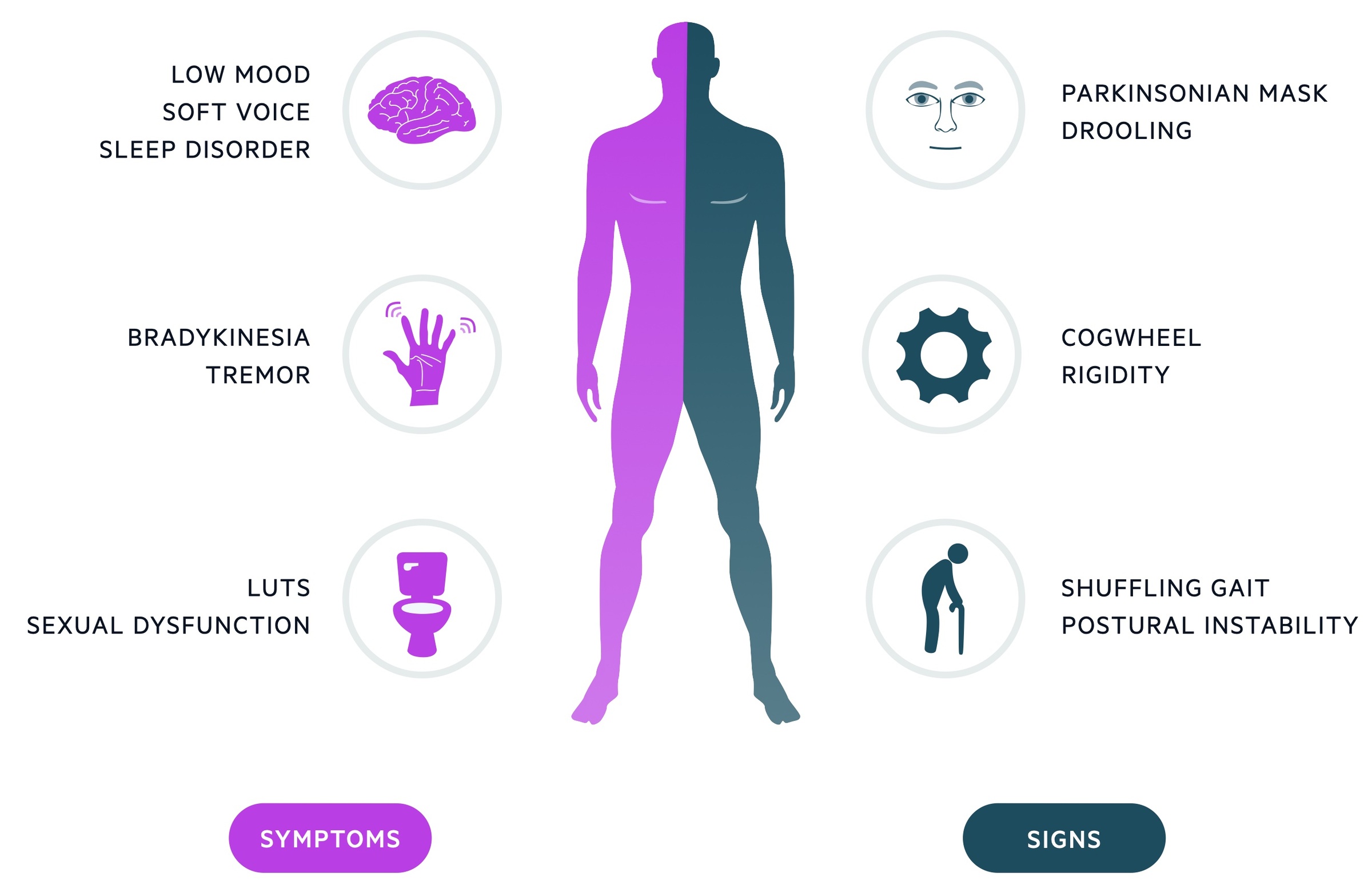

The classic clinical features of Parkinson’s disease are bradykinesia, resting ‘pill-rolling’ tremor and cogwheel rigidity.

Bradykinesia

- A general slowing of voluntary movements

- Reduced arm swing

- Reduction in amplitude with repetitive movements

Tremor

- Traditionally resting and described as ‘pill-rolling’

- 4-6 Hz in frequency

- Can be induced by distraction

Rigidity

- Increase resistance to passive movement

- Cogwheel due to superimposed tremor

Other

- Expressionless face (‘Parkinsonian mask’)

- Micrographia - small writing

- Soft voice

- Drooling of saliva

- Shuffling gait (festinating gait)

- Glabellar tap - repeated tapping of forehead associated with persistent blinking (patient should stop blinking in the absence of pathology)

- Depression

- Bowel & bladder symptoms (urgency, incontinence, constipation)

- Sleep disorder

- Sexual dysfunction

Diagnosis

Parkinson’s disease is a clinical diagnosis and should be suspected based on the presence of bradykinesia and one or more of the other major features of parkinsonism.

Patients suspected of Parkinson’s disease based on the clinical features should be referred to specialist for assessment and diagnosis. Parkinson's disease may be diagnosed using the UK Parkinson's Disease Society (PDS) Brain Bank Clinical Diagnosis Criteria.

Step 1

Step 1 involves the identification of features of parkinsonian syndrome.

Bradykinesia and one of the following:

- Muscular rigidity

- Postural instability

- Resting tremor (4-6 Hz)

Step 2

Step 2 identifies exclusion criteria for Parkinson’s disease.

- Repeated strokes and stepwise progression.

- History of trauma (head injury)

- Definite encephalitis

- > 1 relative affected

- Sustained remission

- Unilateral features after 3 years

- Oculogyric crisis

- Antipsychotic or dopamine-depleting drugs

- Exposure to neurotoxin

- Cerebral tumour or hydrocephalus

- Other atypical neurological features

- Negative response to levodopa

Step 3

Step 3 involves the identification of supportive criteria of Parkinson’s disease.

Three or more of the following:

- Progressive disorder

- Unilateral onset

- Resting tremor

- Persistent asymmetry

- Excellent response to levodopa

- Severe levodopa induced chorea

- Levodopa response ≥ 5 years

- Clinical course of ≥ 10 years

MDS diagnostic criteria

More recently, the movement disorder society (MDS) have released a new diagnostic criteria that outperformed the UK brain bank criteria.

This diagnostic criteria follows a similar methodology to the UK brain bank criteria for reaching a diagnosis.

The diagnosis of clinically established PD is based on:

- Confirmation of Parkinsonism: must be evidence of 'motor' parkinsonism (bradykinesia + tremor or rigidity)

- No absolute exclusion criteria present: multiple exclusion criterias exist. Examples include unequivocal cerebellar abnormalities, vertical supranuclear gaze palsy, parkinsonism restricted to lower limbs ≥3 years, suspected frontotemporal dementia, others.

- ≥2 supportive criteria: dramatic response to dopaminergic drugs, levodopa-induced dyskinesia, rest tremor of limb (typically unilateral onset), others.

- Absence of red flags: rapid development gait impairment, early bulbar dysfunction, non-progressive motor symptoms ≥ 5 years while not on treatment, respiratory dysfunction, early severe autonomic dysfunction, others.

The diagnosis of clinically probable PD is based on:

- Confirmation of Parkinsonism

- No absolute exclusion criteria

- Presence of red flags, but counterbalanced by supportive criteria: no more than two red flags allowed.

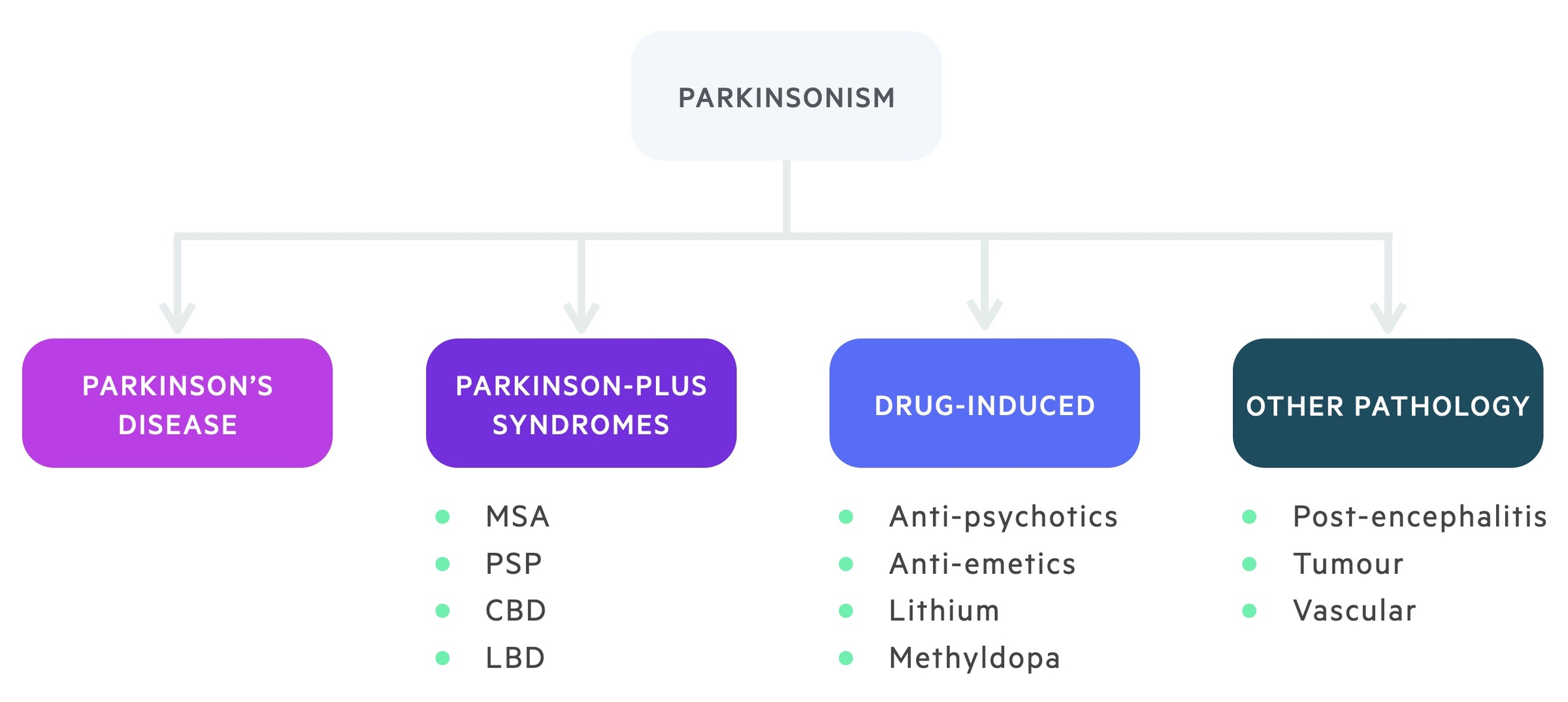

Parkinsonism

Parkinson’s disease is considered an idiopathic cause of parkinsonism.

The main differential diagnoses for Parkinson's disease include other causes of parkinsonism, which described the presence of bradykinesia associated with one or more features from tremor, rigidity and postural instability.

There are numerous causes of parkinsonism, which can be broadly divided into four groups to aid memory: idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, drug-induced, other medical pathology and the Parkinson-plus syndromes.

Parkinson-plus syndromes

The Parkinson-plus syndromes are a group of conditions that may be mistaken for Parkinson’s disease.

Generally, they affect a wider area of the nervous system resulting in more complex disease and atypical presentations. Survival is greatly reduced in these syndromes compared to Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease.

Multi-system atrophy (MSA)

MSA is an adult-onset, rapidly progressive disease that is characterised by profound autonomic dysfunction leading to severe postural hypotension, urogenital dysfunction and a plethora of other features including cerebellar and corticospinal features. There is a poor response to treatment.

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP)

PSP is a neurodegenerative disorder that typically begins at age 50-60 years and is characterised by vertical gaze dysfunction, dysarthria and cognitive decline. Tremor is rare in this condition.

Dementia with Lewy-body (DLB)

DLB is characterised by early onset dementia (< 1 year) with features of parkinsonism. Dementia is usually the proceeding feature prior to motor symptoms and it is characterised by visual hallucination and fluctuating consciousness

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD)

CBD is a neurodegenerative disorder that is characterised by a progressive dementia, parkinsonism and limb apraxia. Apraxia refers to problems with motor planning (i.e. unable to wave hello).

In severe cases CBD may be associated with alien limb syndrome when there is a feeling that the limb is acting on its own.

Investigations

Parkinson’s disease is largely a clinical diagnosis, however, some investigations may be required to rule out an underlying cause.

The important investigation that may be required is neuroimaging (CT/MRI), particularly where there is a strong suspicion of a secondary cause (e.g. cerebrovascular disease) or failed response to treatment.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning with fluorodopa is being increasingly use to help localise dopamine deficiency in the basal ganglia. Although it is predominantly reserved for research at present.

Striatal dopamine transporter imaging using 123I-FP-CIT single-photon emission computed tomography (DaTscan) may be used to differentiate Parkinsonism from essential tremor. It is unable to differentiate different causes of Parkinsonism.

Management

The management of Parkinson’s disease should always involve a multi-disciplinary team as patients will need a wide range of care, especially as the disease progresses.

At present, there are no disease-modifying treatments available for Parkinson’s disease. Treatments mainly work by increasing dopamine levels within the brain. The key to managing Parkinson’s disease is to provide symptom control early and for long as possible whilst minimising any unnecessary side-effects. Treatment should be initiated early following diagnosis.

We will mainly be focusing on treatment of the motor problems in Parkinson’s disease as this is the predominant feature. However, it is essential to remember that patients will require input from other multi-disciplinary professionals including occupational therapists, physiotherapists and dieticians. Treatment of non-motor symptoms may also be required including, for example, constipation (e.g. laxatives), excessive tiredness (e.g. modafinil) or bladder dysfunction (e.g. catheter).

The management options for symptomatic Parkinson’s disease can be broadly divided into three categories: initial therapy, adjuvant therapy and surgical management.

Initial therapy

The main options for the initial management of Parkinson’s disease include Levodopa, dopamine agonists, or monoamine oxidase B inhibitors (MAO-Bs).

Levodopa

Levodopa is the most effective treatment for Parkinson’s disease, which generally gives good motor control fro 4-6 years.

Levodopa is converted into dopamine for use within the brain by DOPA decarboxylase once it crosses the blood brain barrier. Unfortunately, levodopa may be converted into dopamine peripherally as the enzyme is also found outside the brain. To combat this, levodopa is given in combination with a DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor (DDCI),

Levodopa provides the best relief of symptoms with fewest short-term side-effects, however, long-term significant motor complications can occur. This complications can be difficult to control. Consequently, younger patients are often given dopamine agonists in the early stages of treatment.

Dopamine agonists

Dopamine agonists (e.g. ropinirole, pramipexole) work by binding to post-synaptic dopamine receptors. They provide moderate relief of symptoms, can be used in early disease and have less long-term side-effects compared to levodopa. Dopamine agonists are themselves associated with side-effects and one particular issue is the development of impulse-control disorders.

MAO-B inhibitors

MAO-B inhibitors can also be selected as initial therapy in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Rasagiline, a MAO-B inhibitor, works through inhibition of the enzyme monoamine oxidase, which is involved in the breakdown of monoamines, such as dopamine, within the in pre-synaptic neurone. This means more dopamine is available for ordinary function.

Adjuvant therapy

Many patients with Parkinson’s disease will require additional therapy to help control their motor symptoms and will be unable to continue monotherapy. This may mean a combination of the medications previously described (e.g. levodopa, dopamine agonists) or other medications including COMT inhibitors, anti-muscarinics, amantadine or apomorphine.

COMT inhibitors

COMT inhibitors (e.g. Entacapone) inhibit the peripheral breakdown of levodopa by the COMT enzyme allowing more levodopa to cross the blood brain barrier. Therefore, this is an adjuvant therapy in those on levodopa (combination drugs are available).

Others

Anti-muscarinics (e.g. procyclidine) may be used although evidence is poor. Amantadine may be used as early monotherapy or late adjuvant to help with dyskinesia.

Apomorphine, which is a non-selective dopamine agonist, is generally reserved for advanced disease. It is given via subcutaneous injection/infusion, but can cause significant postural hypotension.

Surgical management

There are a number of surgical options that are available for patients in specialist centres that can include thalamic or subthalamic surgery, however, the most commonly used approach is deep brain stimulation.

Deep brain stimulation involves placing electrodes into the basal ganglia that are attached to an internal stimulator. It can reverse akinesia, rigidity and tremor but major complications include intracerebral haemorrhage and confusion.

Complications

The complications of Parkinson’s disease can be broadly divided into ‘Motor’ & ‘Non-motor’ complications.

Motor complications

- Motor ‘on-off’ fluctuations - switch from dyskinesia to immobility in a few minutes

- Dyskinesia - hyperkinetic movement due to dosing of medications

- Freezing of gait - complete inability to move

- 'Wearing off' phenomenon - towards end of dose

- Falls.

Non-motor complications

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Nutritional deficiency, dysphagia & weight loss

- Bladder, bowel & sexual dysfunction

- Pressure sores

- Sleep disorders

- Dementia & depression

- Postural hypotension

- Impulse control disorders and psychosis

Last updated: April 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback