Status epilepticus

Notes

Overview

Status epilepticus refers to continuous seizure activity, which has failed to self-terminate.

Status epilepticus (SE) or ‘status’ is medical emergency. More than 15% of patients with epilepsy will have at least one episode of SE, which can be life-threatening. It is traditionally defined by the duration of continuous seizure activity and effect on consciousness.

Traditional definition

- A single epileptic seizure lasting > 30 minutes

- A run of epileptic seizures (≥2) without regaining consciousness between episodes

The majority of seizures will spontaneously terminate within 3 minutes and do not require emergency treatment. However, those with sustained seizures are at risk of long-term neurological damage. The highest risk is with generalised tonic-clonic seizures.

Practical definition

In clinical practice, there is urgency to treat SE to prevent irreversible neurological damage. This means the traditional definitions may not be practical.

Instead, patients should be treated as SE if they have the following:

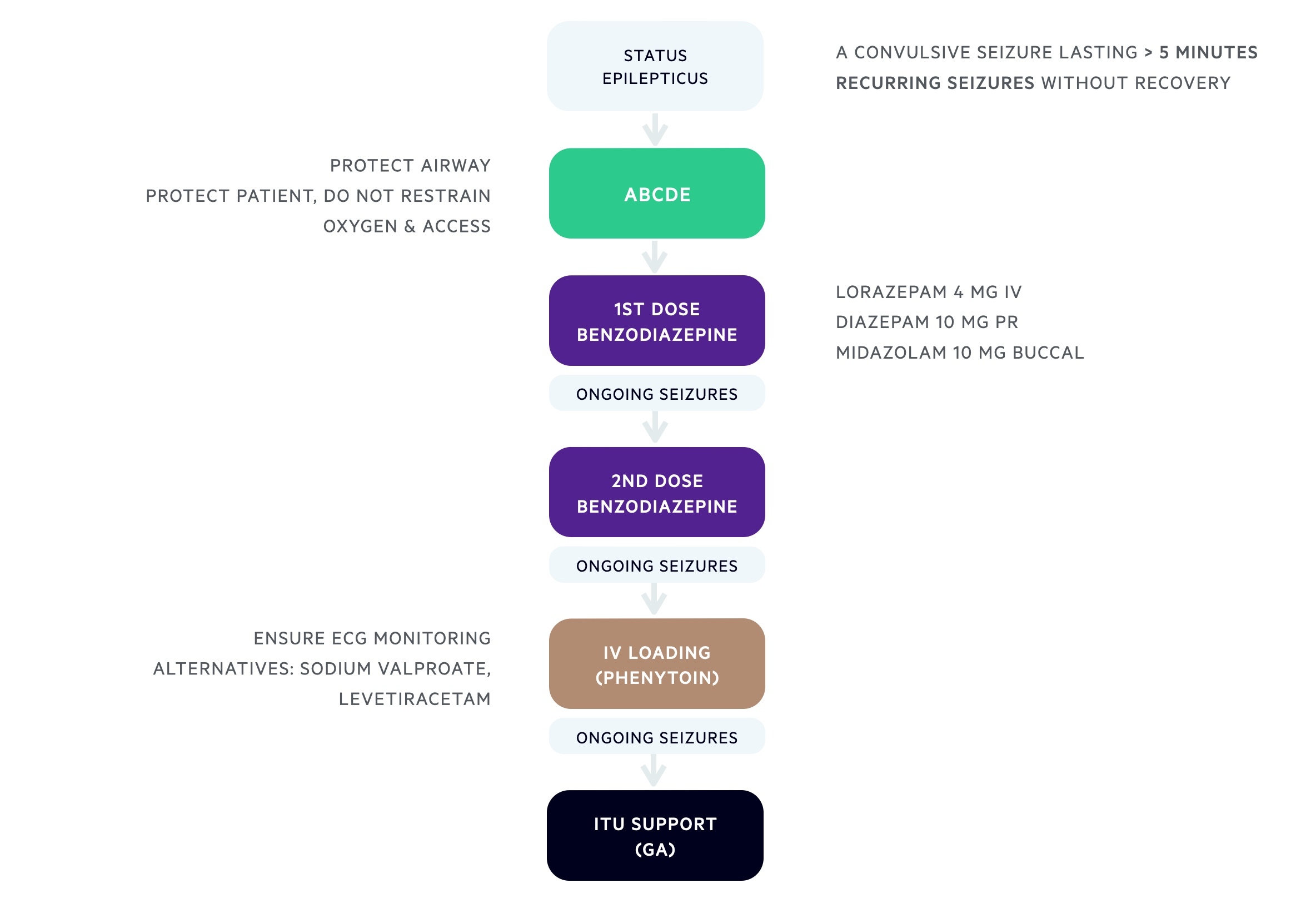

- A convulsive seizure lasting > 5 minutes

- Recurring seizures without recovery

Types

Status epilepticus can be divided into convulsive and non-convulsive status.

Convulsive

Convulsive SE is used to describe the typical, sustained generalised tonic-clonic seizure, which presents with generalised muscle stiffening and rhythmic muscle jerking. Other types may include myoclonic status, tonic status and focal motor status.

A background of epilepsy is single strongest risk factor for generalised convulsive SE

Non-convulsive

Non-convulsive SE is used to describe a long or repeated absence or focal impaired awareness seizure. These patients do not have classical convulsive movements that make it easy to recognise. Instead, it usually requires a high degree of suspicion and evidence of epileptiform activity on electroencephalogram (EEG).

Clinical features may include altered mental status, subtle twitching or myoclonic jerks, unusual behaviour or speech disturbance.

Assessment - pre-hospital

In the pre-hospital setting, patients with known epilepsy may develop seizures that self-terminate and do not require medical attention.

The need for medical attention depends on the underlying illness, type of epilepsy, complications from seizure or risk of SE.

Basic seizure first aid:

- STAY: remain with the patient until recovery, note the time, call for help (if needed)

- SAFE: keep the patient safe, move or guide from harms way

- SIDE: turn patient on their side, keep airway clear, cushion head, loosen tight fitting clothes

- DON’T: restrain, place items in mouth

- CONSIDER: rescue medications* if a trained medical professional or trained carer

- CALL: 999 if seizure > 5 minutes, no return to normal state, injured, pregnant or sick, first seizure, repeated seizures, difficulty in breathing, seizure in water.

*NOTE: rescue medications may be prescribed for patients known to have recurrent seizures. They can include buccal midazolam or rectal diazepam.

Assessment - hospital

Any seizure in hospital should be treated as a medical emergency.

In a hospital setting, it may be difficult to determine whether a seizure will spontaneously terminate or require treatment for SE. This is especially true if a seizure is witnessed or there is no delay in assessment (< 5 minutes). Therefore, any seizure developing in hospital should be treated as a medical emergency and managed with a structured ABCDE approach.

We can divide the assessment and management of seizures into different stages based on seizure duration.

1st stage (0-10 minutes): early status

- Check for safety and call for help

- Assess the patient with respect to ABCDE (airway, breathing, circulation, disability, exposure)

- Protect the airway and provide oxygen therapy

- Protect the patient, but do not restrain

- Establish IV access*

*NOTE: bloods can be taken at the same time for a venous blood count, full blood count, urea & electrolytes, coagulation, glucose, bone profile, magnesium, liver function tests, anti-convulsant drug levels, cultures (if appropriate)

2nd stage (0-30 minutes)

- Regular monitoring (e.g. cycling observations, ECG monitoring if possible, temperature)

- Emergency AED therapy (see acute seizure management)

- Emergency investigations (bloods, CXR, toxicology screen)

- Consider alcohol intoxication: consider Parbinex

- Blood glucose level: consider intravenous glucose (e.g. 100 mls 20%)

3rd stage (0-60 minutes): established status

- Determine aetiology (collateral history, hospital records, etc)

- Further emergency AEDs as needed (see acute seizure management)

- Alert anaesthetic team and intensive treatment unit (ITU)

- Treat any co-morbidities (i.e. sepsis)

- Consider urgent CT head (e.g. exclude intracerebral bleed, structural abnormalities)

4th stage (30-90 minutes): refractory status

- Transfer to ITU: requires general anaesthesia with intubation and ventilation

- EEG monitoring

Acute seizure management

Emergency anti-epileptic drugs are critical to seizure control.

First-line pharmacological therapy

Benzodiazepines are the cornerstone of initial seizure treatment. It is essential to check whether any pre-hospital benzodiazepines have already been administered.

For adults:

- Lorazepam 4 mg IV, if unavailable;

- Diazepam 10 mg PR, if unavailable;

- Midazolam 10 mg buccal

Second-line pharmacological therapy

A further single dose of benzodiazepine can be administered within 10-20 minutes if seizures have not been controlled. Ensure usual AEDs have been administered.

For adults:

- Lorazepam 4 mg IV, if unavailable;

- Diazepam 10 mg PR, if unavailable;

- Midazolam 10 mg buccal

Third-line pharmacological therapy

If the seizure has not been controlled by two doses of benzodiazepine, patients require loading (i.e. IV infusion) of a 2nd line AED.

At present, phenytoin is the only licensed agent, but other AEDs are being increasingly used. Always check local hospital SE guidelines.

For adults:

- Phenytoin: 20 mg/kg, requires ECG monitoring. May be preferred if contraindications to alternatives or already established on phenytoin and suspected poor adherence. Key side-effects: hypotension, bradycardia, heart block

- Sodium valproate: 30 mg/kg (max 3000 mg), avoid if known pregnancy or childbearing age. May be preferred if already established on sodium valproate but suspected poor adherence or past medical history of migraines or mood disorders. Key side-effects: drug induced liver injury, pancreatitis.

- Levetiracetam: 40 mg/kg (max 4500 mg). May be preferred if contraindications to alternatives or already established on levetiracetam and suspected poor adherence. Minimal drug interactions. Key side-effects: known mood/behaviour disorder.

Refractory status

If a patient is refractory to previous medications, they should be referred to ITU for general anaesthesia with intubation and ventilation. Anaesthesia should be continued for a minimum of 12-24 hours and guided by EEG monitoring.

Options:

- Propofol

- Midazolam

- Thiopental sodium

Non-convulsive therapy

Patients with non-convulsive status require discussion with neurology for specialist advice on management.

Ongoing management

All patients with SE should be discussed with the specialist neurology team and ideally reviewed within 24 hours.

Patients presenting with their first seizure will require consideration of maintenance AEDs depending on the suspected underlying cause. This should involve formal discussion with neurology.

Those who already have a diagnosis of epilepsy require optimisation of their current medication. Follow-up and routine review can be arranged as necessary on discharge.

Complications

SE can be fatal or associated with long-term neurological morbidity.

Major acute complications include:

- Acute: hyperthermia, cardiac arrhythmias, severe hypoxaemia, shock, cerebral oedema

- Chronic: long-term neurological damage (epilepsy, focal neurological deficits, encephalopathy)

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback