Cord compression

Notes

Defintion

Malignant cord compression is defined by radiological evidence of indentation of the thecal sac secondary to cancer.

The spinal cord is part of the central nervous system (CNS) and forms the main communication between the brain and peripheral nerves. It is surrounded by the meninges, the dura, arachnoid and pia mater. The thecal sac is a component of the dura mater (the outermost meningeal layer).

Due to the similar pathophysiological processes, cauda equina syndrome due to cancer is normally incorporated under the heading of malignant cord compression. The cauda equina refers to the collection of lumbar, sacral and coccygeal nerve roots that descend from the end of the spinal cord at L1.

It is estimated that 5-10% of patients with cancer will develop metastatic lesions that effect the spinal cord. The overall burden of cord compression varies dependent on the underlying malignancy. Pancreatic cancers have a small burden at 0.2% compared to multiple myeloma at 7.9%. In approximately 20% of cases of malignant cord compression, it is the first presentation of the underlying cancer.

Anatomy

The spinal cord is part of the central nervous system (CNS) and forms the main communication between the brain and peripheral nerves.

The spinal cord originates at the base of the medulla oblongata, exiting the skull through the foramen magnum. It then extends through the spinal canal and ends at the level of the L1/L2 spinal vertebrae.

It is divided into four main regions termed cervical, thoracic, lumbar and sacral. This is further divided into 31 spinal cord segments. Arising from the 31 cord segments are the paired ventral and dorsal spinal nerve roots, which join to form the 31 paired spinal nerves.

The terminal end of the spinal cord is termed the conus medullaris. Beyond this is a collection of spinal nerves composed of lumbar, sacral and coccygeal nerves. Together these make up the cauda equina or 'horses tail'.

The white matter is composed of myelinated axons, which form ascending and descending tracts. White matter tracts are important for the transmission of motor, sensory and autonomic information between the central and peripheral nervous system.

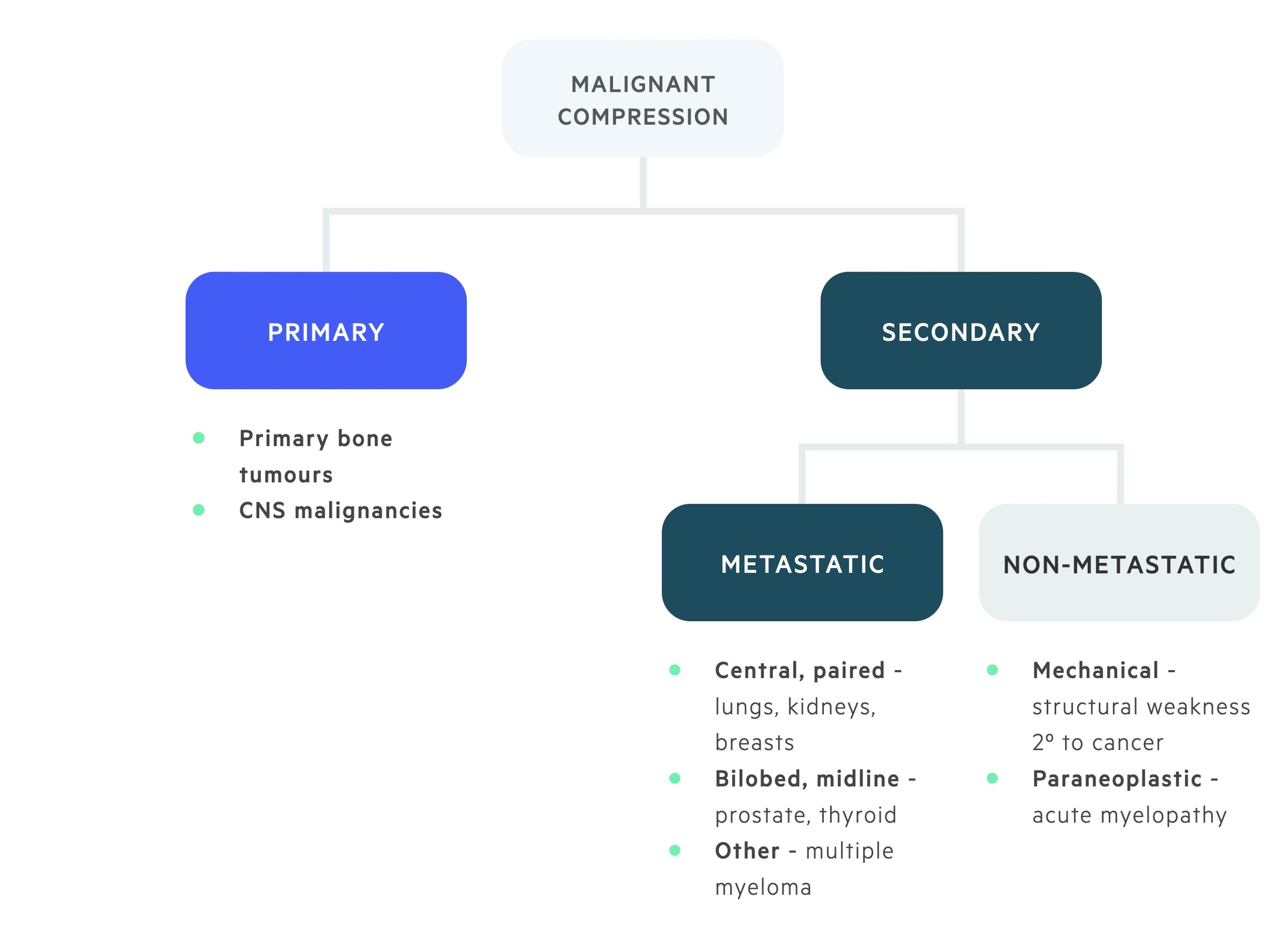

Aetiology

Malignant spinal cord compression usually occurs secondary to metastatic deposits within the spinal column.

Lung, breast, kidney, prostate and thyroid cancers are associated with cord compression secondary to metastatic disease. Compression may also result from mechanical dysfunction occurring as a result of malignant disease. Primary CNS tumours can also lead to cord compression.

It is important to recognise that there are other causes of cord compression.

- Trauma

- Intervertebral disc prolapse

- Haematoma

- Epidural abscess (secondary to osteomyelitis or discitis)

- Cervical spondylitic myelopathy

Pathophysiology

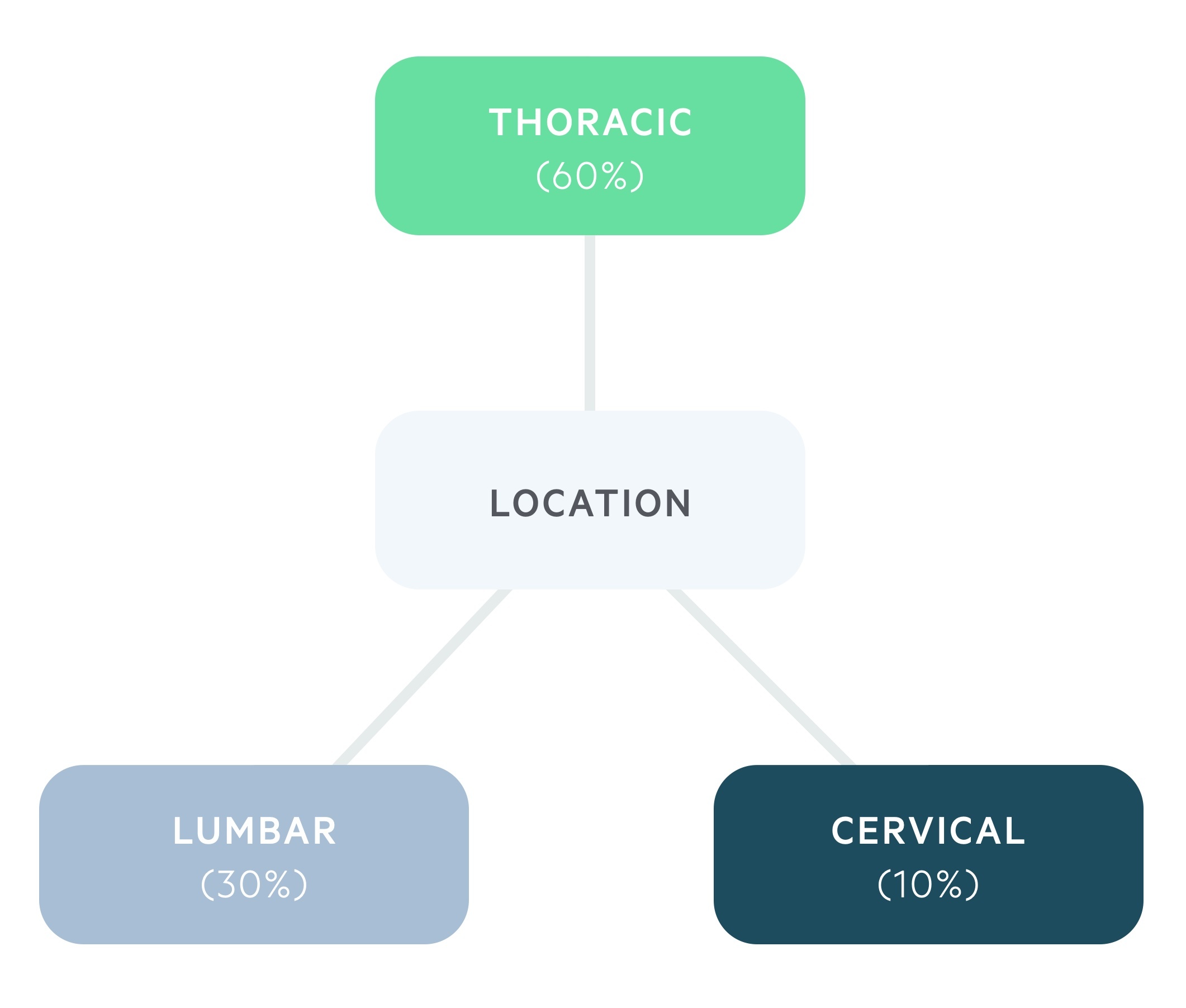

Malignant cord compression most commonly occurs in the thoracic spine.

Approximately 60% of cases occur in the thoracic spine, 30% in the lumbar spine and 10% within the cervical spine.

Cord compression occurs when a tumour invades into the epidural space and compresses the thecal sac. The more extensive the compression of the thecal sac and thus the spinal cord, the more likely there will be significant neurological symptoms.

Most cases of malignant cord compression (85-90%) occur secondary to metastatic extension from the vertebral bodies. This means pressure on the thecal sac tends occurs anteriorly.

There are multiple causes of vertebral metastasis, it may be related to arterial seeding, shunting of blood through the epidural venous plexus (strongly implicated in prostate cancer) or extension through the intervertebral foramina (through which the spinal nerves exit).

Clinical features

Good neurological recovery from malignant cord compression relies on early recognition and treatment.

Signs and symptoms may initially be subtle and diagnosis may require a high degree of suspicion. Clinical features include pain, motor symptoms, sensory symptoms and bladder and bowel involvement.

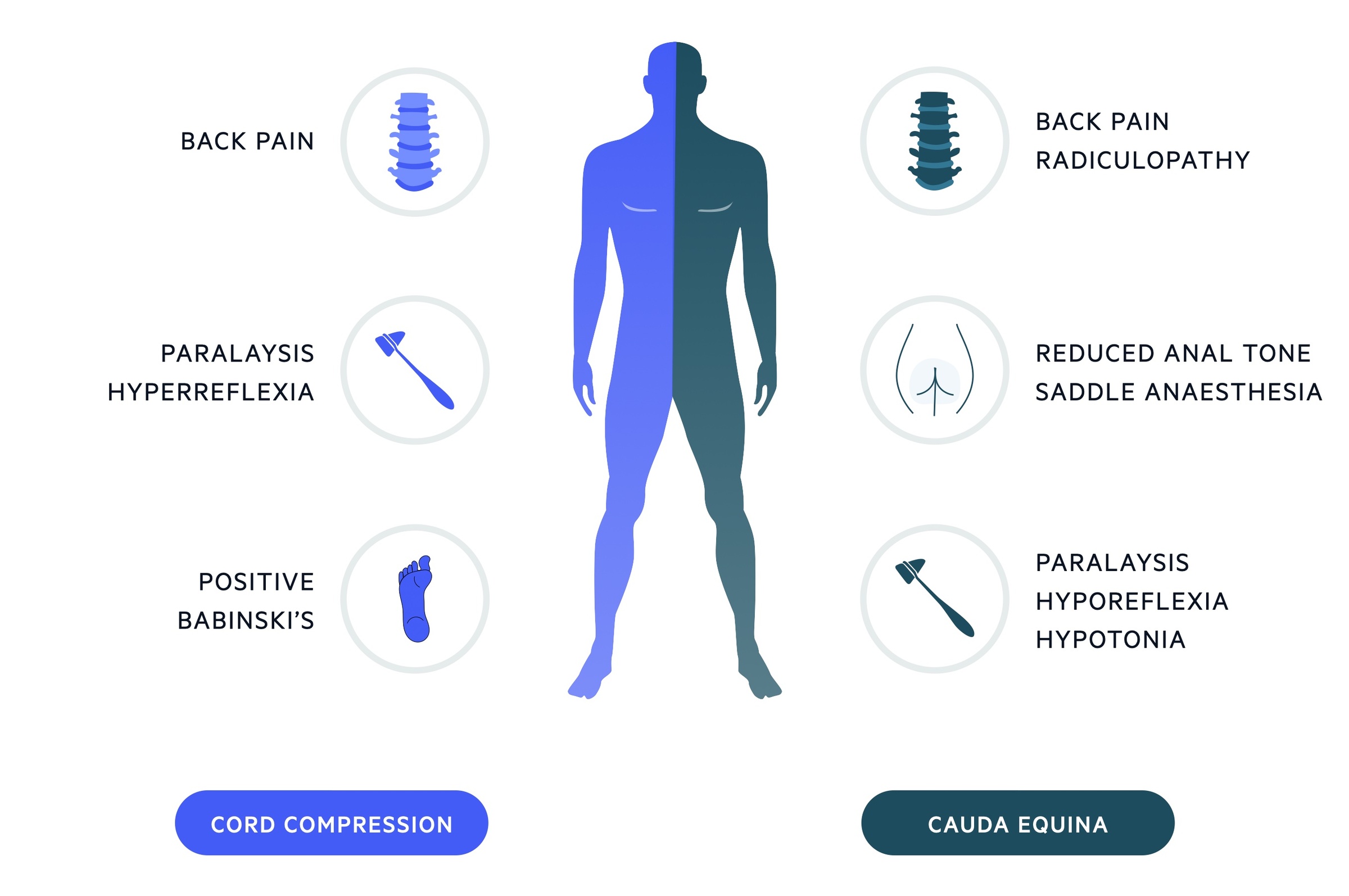

Cord compression

Pain features in up to 95% of presentations. It usually precedes the development of neurological symptoms by several weeks. Pain is typically severe, progressive and may develop a radicular character.

Weakness, typically symmetrical, is common and seen in up to 85% of patients at diagnosis. It is characteristically pyramidal (i.e. preferentially affects the extensors in the upper extremities and the flexors in the lower extremities). Weakness is usually progressive with the development disturbed gait and eventually paralysis.

Upper motor neurone lesions tend to result in increased tone. Hyperreflexia below the level of the lesion with extensor plantar reflex (positive Babinski) may be found on examination. Sensory symptoms are less common than motor symptoms. Patients may complain of paraesthesia peripherally and there is usually a sensory level.

Cauda equina

Compression of the cauda equina results in a lower motor neurone pattern and features are frequently unilateral. It is characterised by saddle anaesthesia, reduced anal tone and painless urinary retention (and overflow incontinence).

Lower back pain, that may be both local and radicular, is common. Additional features may include impotence and absent ankle jerk.

It is important to remember that disease may affect both the cord and cauda equina leading to a mixed picture.

Investigations & diagnosis

An MRI scan is the investigation of choice in suspected malignant cord compression.

An MRI allows determination of the extent of disease and accurate identification of the site of compression.

Other possible imaging modalities are listed below.

- Myelography

- Computed tomography

- Bone scan

- Plain radiographs

Management

Acute cord compression and cauda equina syndrome are surgical emergencies requiring prompt recognition and treatment.

General measures

Patients should receive adequate analgesia utilising the WHO analgesic ladder. In cases of refractory pain, advice should be sought from the Pain Team. VTE prophylaxis is key as these patients are at increased risk of thromboembolic events. In the absence of contraindications, TED stockings and prophylactic LMWH should be used. A catheter may be used to manage any bladder dysfunction.

Glucocorticoids

Dexamethasone (normally high-dose) can be used as part of the initial treatment. Its is thought to reduce oedema helping to relieve compression.

Definitive procedures

External beam radiotherapy may be used as an adjuvant to surgery or a definitive stand-alone therapy in those unable to undergo surgical intervention. It is normally well tolerated and provides good local tumour control and pain relief.

Stereotactic body radiotherapy is a technique that enables higher doses of radiotherapy to be targeted more directly at the tumour while minimising exposure to adjacent tissue. Evidence indicates that stereotactic body radiotherapy may be useful against fairly radioresistant neoplasms (e.g. sarcoma, renal cell carcinoma). There is approximately a 10-15% risk of vertebral collapse with this type of radiotherapy.

Surgical management options include surgical decompression and reconstruction, vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty. Surgical decompression tends to be the management of choice in patients with an unstable spine or radioresistant tumours. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty can be used in patients unable to undergo full surgical decompression and reconstruction.

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback