Malignant hypercalcaemia

Notes

Defintion

Malignant hypercalcaemia is defined as a serum calcium > 2.6 mmol/L, secondary to a malignant process.

It is the most common cause of hypercalcaemia in the inpatient population and the second most amongst the general population (after primary hyperparathyroidism). It is generally a negative prognostic factor and may complicate 20-30% of malignancies.

Calcium physiology

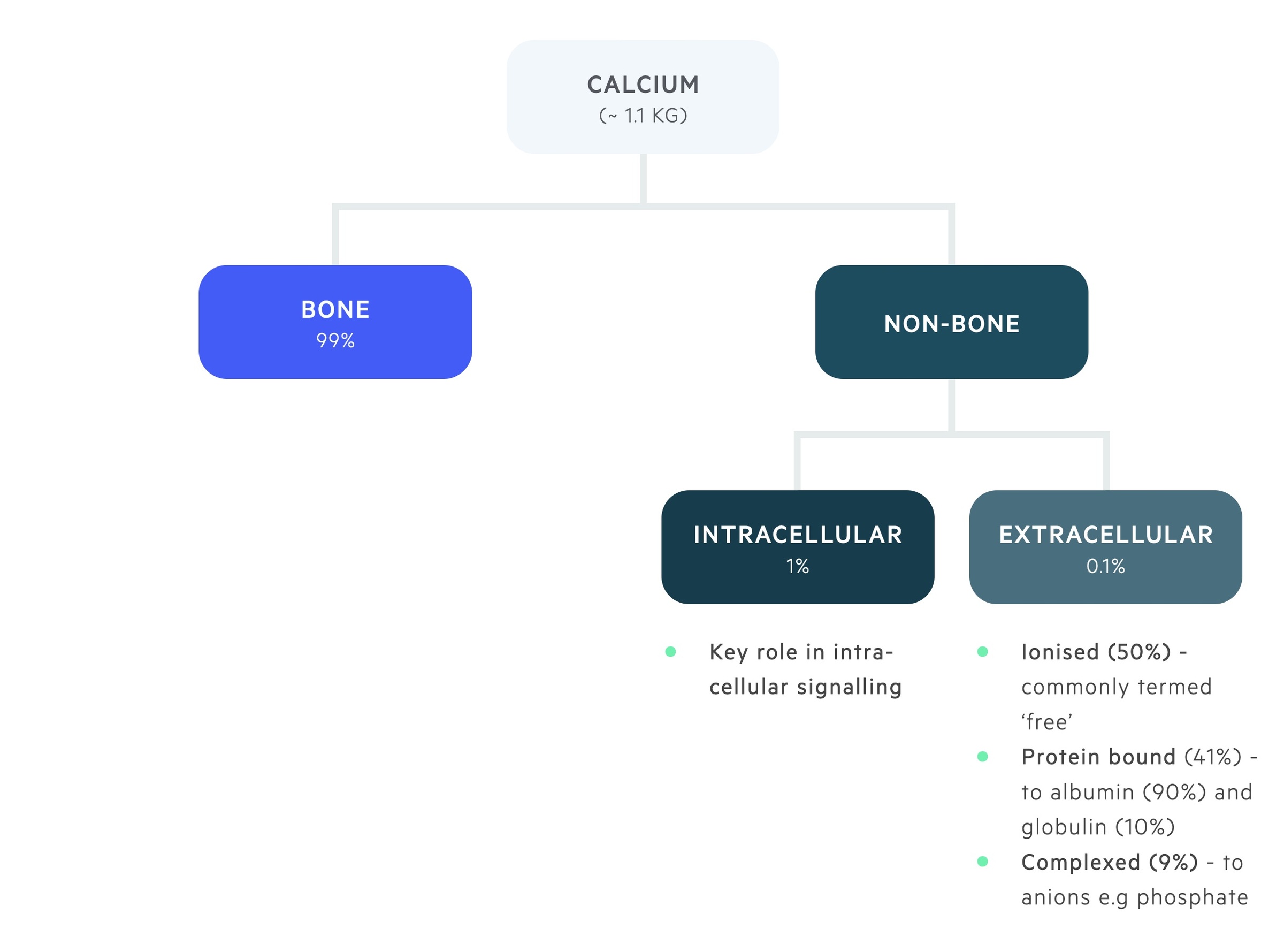

Calcium is distribuited between bone and the intra- and extra-cellular compartments.

The majority of body calcium, 99%, is stored in bone. 1% of total body calcium is found within the intracellular compartment. Here it plays a key role in intracellular signalling.

0.1% of total body calcium is found within the extracellular pool, this is divided into:

- Ionised (50%) - metabolically active, or ‘ionised’, free pool of calcium.

- Bound (41%) - bound to albumin (90%) and globulin (10%).

- Complexed (9%) - forms complexes with phosphate and citrate.

The balance between stored calcium and the extracellular pool of calcium is a closely regulated process. It is controlled by the interaction of three hormones; parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D and calcitonin.

Decreased extracellular calcium is detected by the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) on the parathyroid gland. The parathyroid glands respond to the fall in serum calcium by releasing PTH. PTH stimulates the resorption of calcium from bone, activation of vitamin D (leads to calcium absorption from enterocytes) and increased renal tubular reabsorption of calcium.

Conversely, a rise in extracellular calcium detected by the CaSR has the opposite effect. It leads to a reduction in the release of PTH and stimulates the release of calcitonin. This combined effect helps decrease bone resorption and promotes calcium excretion in the kidneys.

Serum calcium

Normal serum calcium levels range from 2.2-2.6 mmol/L. Levels > 2.6 mmol/L are defined as hypercalcaemia. Depending on the level of serum calcium, hypercalcaemia can be graded:

- Mild: 2.6-3.0 mmol/L

- Moderate: 3.0-3.5 mmol/L

- Severe: > 3.5 mmol/L

The proportion of extracellular calcium that is ionised or 'free' is dependent on the amount bound to albumin. Serum calcium must be 'corrected' with reference to albumin levels. Typically 0.1 mmol/L is added to the level for every 4 g/L below 40 g/L the albumin is, with a subtraction if it is above 40 g/L.

Interestingly, protein binding of calcium is altered by pH. Acidosis leads to a decrease in calcium binding with albumin and alkalosis an increase.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

Primary hyperparathyroidism and malignant hypercalcaemia are responsible for 90% of cases of hypercalcaemia.

The most common malignancies associated with hypercalcaemia are breast cancer, multiple myeloma, lymphoma and lung cancer (e.g. squamous cell carcinoma).

There are three main mechanisms that cause malignant hypercalcaemia:

- Osteolytic metastasis

- PTH-related protein (PTHrP) secretion

- Increased 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D production

PTHrP secretion

PTHrP is a normal gene product of a variety of different tissues, including neuroendocrine and epithelial. The release of PTHrP from tumour cells is the most common cause of malignant hypercalcaemia occurring in approximately 80% of cases. Solid tumours such as breast carcinomas and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma are common causes.

Malignant hypercalcaemia related to PTHrP secretion is often termed humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy (HHM). PTHrP is structurally similar to PTH and leads to increased bone resorption, distal renal tubular calcium absorption and inhibition of proximal phosphate transport. Unlike PTH, PTHrP is less likely to lead to activation of vitamin D.

Osteolytic metastasis

Osteolytic metastasis accounts for approximately 20% of cases of malignant hypercalcaemia. It is most commonly associated with breast cancer.

In osteolytic metastasis, deposition of tumour cells within bone leads to local production of inflammatory cytokines and other mediators stimulating osteoclasts, leading to bone resorption.

1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D production

Increased activated vitamin D levels lead to increased absorption of calcium from gastrointestinal enterocytes. The increased expression of activated vitamin D is the most common cause of malignant hypercalcaemia in Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL).

This process may also be seen in chronic granulomatous diseases (e.g sarcoidosis).

Clinical features

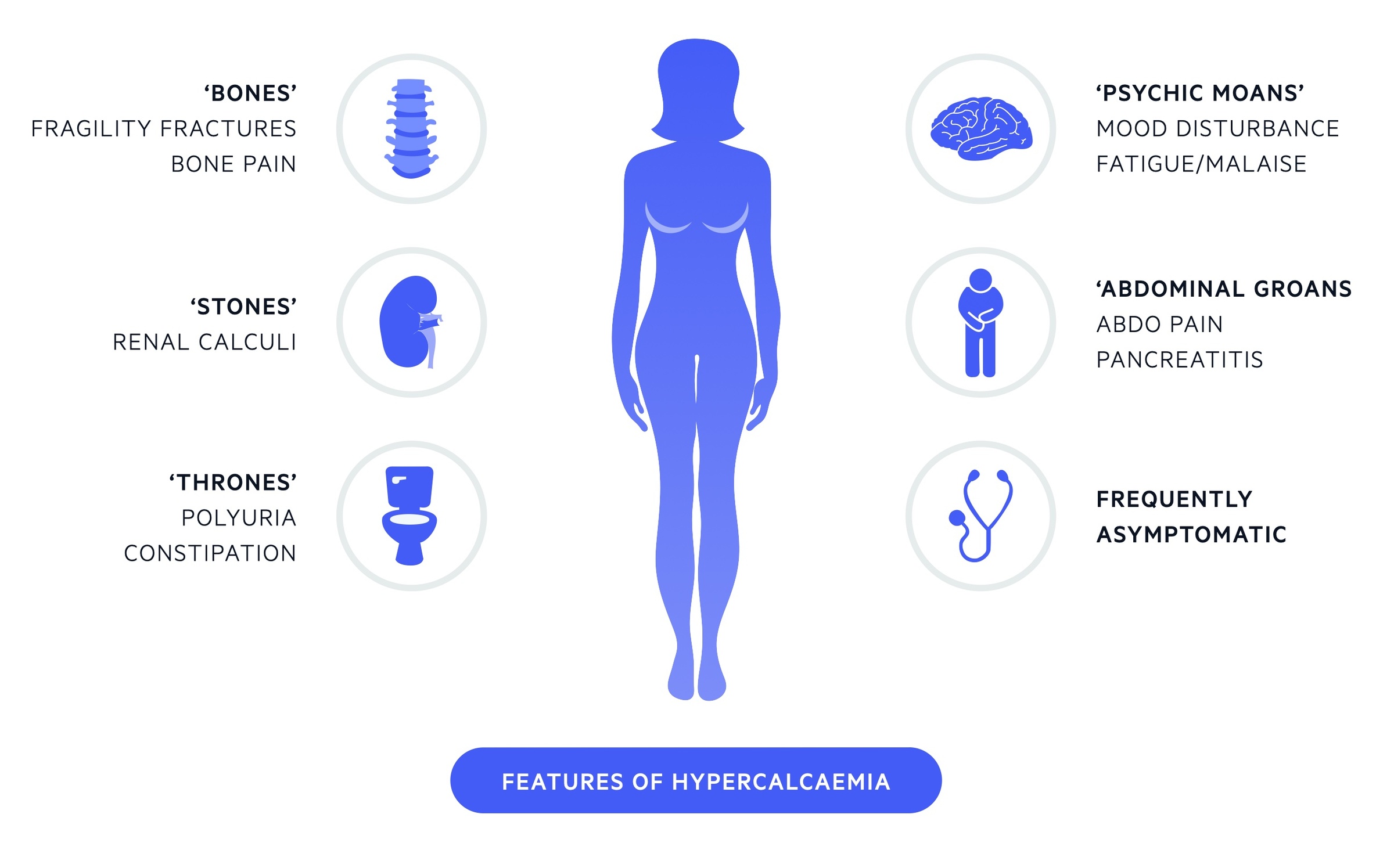

'Stones, bones, thrones, abdominal groans and psychiatric moans’. (Renal stones, bone pain, polyuria, abdominal pain and psychiatric features)

It is important to remember many patients will be entirely asymptomatic or dismiss mild symptoms even with significantly elevated calcium levels.

Mild hypercalcaemia

- Often asymptomatic

- Polyuria

- Polydipsia

- Mild cognitive impairment

- Dyspepsia

Moderate hypercalcaemia

- All mild features

- Constipation

- Weakness

- Fatigue

- Dehydration

- Nausea

Severe hypercalcaemia

- All mild and moderate features

- Abdominal pain

- Vomiting

- Cardiac dysrhythmias

- Pancreatitis

- Coma

Investigations & diagnosis

The diagnosis of malignant hypercalcaemia is based on measurement of the serum calcium level and identification of an underlying cancer.

Malignant causes of hypercalcaemia frequently cause a rapid increase in serum calcium levels, whereas benign causes of hypercalcaemia usually have a more prolonged and asymptomatic course.

Biochemical markers may be used to help differentiate between primary hyperparathyroidism and malignant hypercalcaemia. In malignant hypercalcaemia the PTH should be suppressed.

A full examination (including breast exam) should be completed and documented. Investigations should be targeted at the potential underlying causes and a myeloma screen (immunoglobulins, protein electrophoresis and urinary light chains) is normally indicated. Imaging, typically CT, may be required.

Management

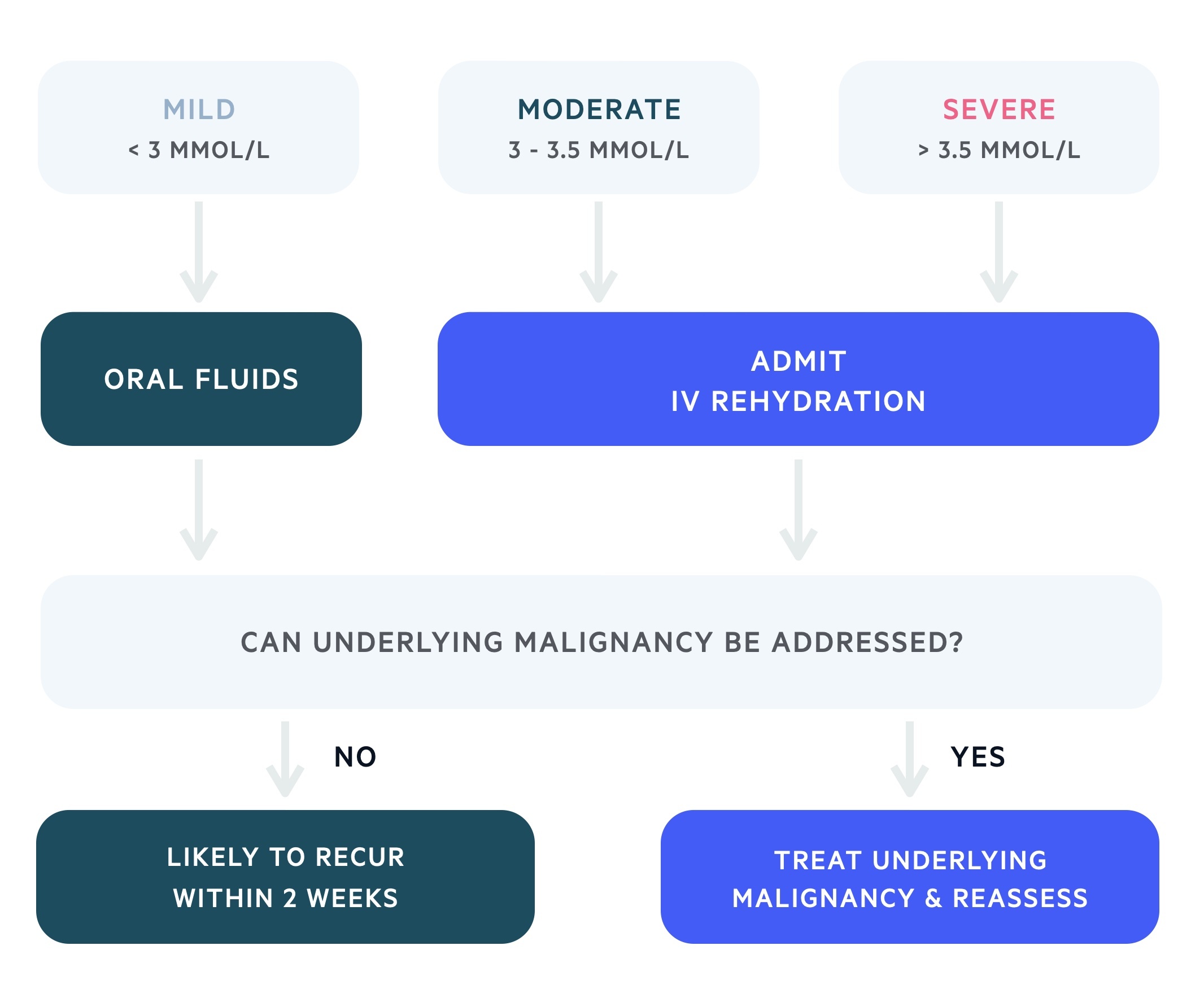

Intravenous rehydration is the most important component of management in moderate or severe malignant hypercalcaemia.

The management of malignant hypercalcaemia depends on the clinical presentation, the absolute level of serum calcium and the velocity of serum calcium rise. Most clinicians will admit at a lower serum calcium in patients with malignant hypercalcaemia when compared to primary hyperparathyroidism.

Hypercalcaemia may be managed with IV hydration, calcitonin and bisphosphonate therapy. NICE recommend admission for any patient with a serum calcium > 3 mmol/L (or anyone symptomatic) and underlying malignancy. Those with a serum calcium < 3 mmol/l may be managed as an outpatient with oral hydration (3-4 L/day) and regular review.

In those in whom it is appropriate, the underlying malignancy should be addressed to offer lasting correction.

Additional therapies depend on the response to treatment and severity of the condition. These may include glucocorticoids, denosumab (monoclonal antibody targeted against RANKL) and dialysis.

IV hydration

Aggressive fluid rehydration should be commenced in patients with moderate or severe disease. The use of normal saline helps to restore intravascular volume and prompts a calcium diuresis. In those with renal or heart failure loop diuretics may be required, this should prompt specialist input.

Calcitonin

Calcitonin may be given to a patient with moderate or severe hypercalcaemia. It works by promoting urinary calcium excretion and inhibits bone resorption. Its action begins after a few hours in those sensitive to its actions and lasts a few days.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates are analogues of inorganic pyrophosphate. They are absorbed onto the surface of the boney network and work by inhibiting the action of osteoclasts.

It takes several days (2-4) before their action is noticed but they provide calcium-lowering effects over a prolonged period (2-4 weeks). Pamidronate or zoledronic acid are typically used.

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback