ADPKD

Notes

Overview

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease is a common genetic disorder characterised by multiple renal cysts.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is due to inheritance of the abnormal genes PKD1 or PKD2 that is thought to occur in around 1 in 1000 live births.

The disease is characterised by development of multiple renal cyst and progressive renal impairment, which leads to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in around 50% of patients by 60 years of age. It accounts for up to 10% of patients with ESRD.

ADPKD is generally a condition of adults and rarely presents in childhood. The estimated median age of developing ESRD is in 6th decade for PKD1 and 8th decade for PKD2.

Aetiology

The majority of cases of ADPKD are due to PKD1 or PKD2 mutations.

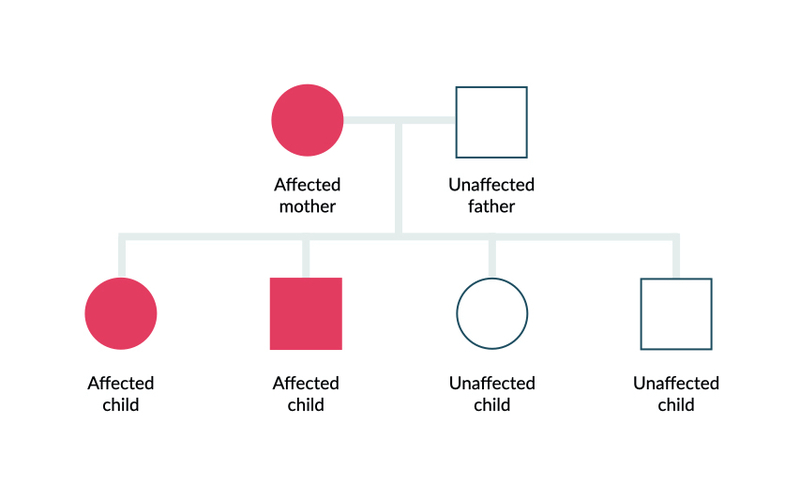

As the name suggests, ADPKD is an autosomal dominant inherited condition due to a mutation within the PKD1 or PKD2 gene. Autosomal dominant means only a single abnormal copy of the gene is needed to express the phenotypes (i.e. the clinical features of the disease). If one parent has the condition, there is a 50% chance of passing it to their offspring.

Autosomal dominant inheritance

Rarely, a third form has been identified known as PKD3, which has been linked to several genes including GANAB.

Polycystic kidney disease type 1

The gene PKD1 is located on chromosome 16 and encodes the protein polycystin-1. This protein is involved in cell adhesion through protein-protein, cell-cell, and/or cell-matrix interactions thought to be due to regulation of calcium influx.

PKD1 accounts for the majority of cases (74-96%; depending on study) and has a more severe phenotype associated with earlier onset renal impairment.

Polycystic kidney disease type 2

The gene PKD2 is located on chromosome 4 and encodes the protein polycystin-2. It is a type of calcium-permeable channel transmembrane proteins, which co-localises with polycystin-1.

PKD2 accounts for approximately 15% of ADPKD and has a less severe phenotype.

Pathophysiology

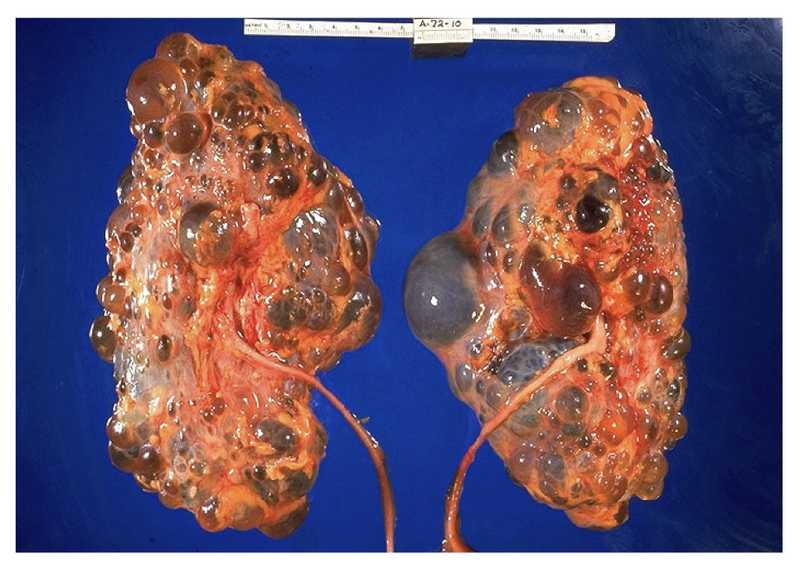

The hallmark of ADPKD is develop of multiple renal cysts.

In ADPKD, all cells contain the inherited genetic mutation in PKD1 or PKD2. However, < 1% of nephrons within the kidneys become abnormally cystic. This means that further genetic alterations (e.g. somatic mutation) need to occur within tubular cells of nephrons, which lead to the development of cysts.

Early cyst development can occur in any aspect of the nephron, but usually distal regions. There is dilatation and out-pouching of the tubule wall, which leads to the development of cysts with fluid from the glomerular filtration.

Overtime, these cysts separate from the nephron, which leads an isolated sac. Ongoing fluid accumulation is achieved through secretion of fluid into the cysts by transepithelial transport and autonomous growth. There is continued epithelial hyperpalsia, fluid secretion, membrane alterations and fibrosis of the interstitium. Collectively, this leads to massive cystic disease and impaired renal function.

The proteins polycystin-1 and polycystin-2 can be found in a variety of other tissues including hepatic ducts and pancreatic ducts. Therefore, it is unsurprising that ADPKD can present with extra-renal cystic disease affecting the liver and pancreas.

Pathological specimen of massive polycystic kidneys.

Clinical features

ADPKD may be asymptomatic for many years until picked up on screening or abnormal blood tests.

Symptoms

- Abdominal, flank or back pain: due to large size or cyst complications (rupture/infection)

- Haematuria: typically occurs in association with ruptured cyst

- Dysuria and fever: suggestive of urinary tract infection or infected cyst

- Renal colic: nephrolithiasis (i.e. stones) more common

- Constitutional features of chronic kidney disease: fatigue, weakness, reduced energy

- Polyuria, polydipsia, nocturia: excess urine due to poor concentrating ability of kidneys (i.e. not responding to anti-diuretic hormone)

Signs

- Bilateral flank masses: due to large polycystic kidneys

- Hepatomegaly: if polycystic liver disease

- Hypertension: seen in most patients by 4th decade of life (even if normal renal function)

Cyst complications

- Ruptured cyst: common cause of loin pain, usually self-limiting

- Haemorrhagic cyst: describes a ruptured cyst with haemorrhage. If occurs into the collecting system can be associated with visible haematuria. Loin pain common as with ruptured cysts. Most self-limiting within 7 days.

- Infected cyst: many occur in relation to rupture. Typical features include fever, pain, dysuria.

Extra-renal manifestations

- Polycystic liver disease: seen in > 80% of patients on MRI imaging. Poor correlation with renal cysts. Women generally affected at younger age and more severely.

- Pancreatic cysts: seen in up to 36% of patients.

- Cerebral aneurysms: four times higher compared to general population. 8-12% of patients. Rupture most serious complication of ADPKD.

- Cardiac valve disease: seen in 25-30%. Most commonly mitral valve prolapse and aortic regurgitation.

- Gastrointestinal abnormalities: diverticulosis and hernias (abdominal/inguinal) occur at higher frequency

- Seminal vesicle cysts and infertility: vesicle cysts in up to 40% of males. Rarely causes infertility. ADPKD also associated with poor sperm motility.

Diagnosis

Patients may be diagnosed incidentally, following presentation with typical clinical features, or during screening.

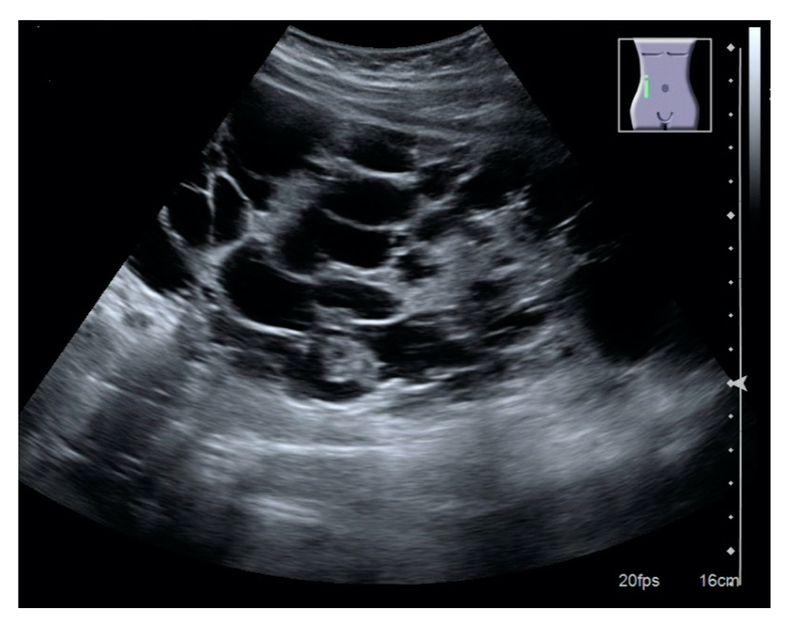

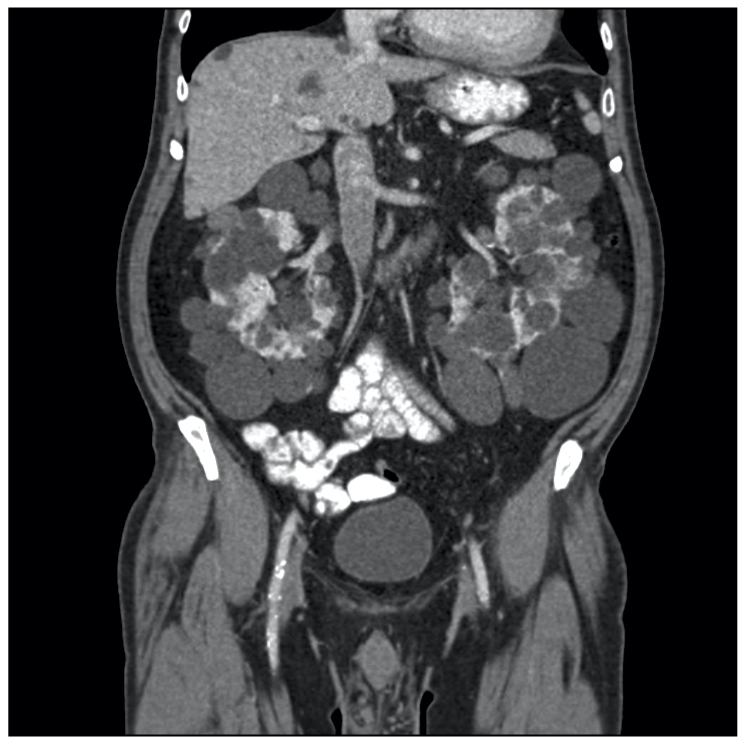

The diagnosis of ADPKD is primarily made on imaging with identification of multiple bilateral renal cysts. The principle imaging modality is ultrasound, but MRI and CT have an increasing role. Most newer ultrasound machines can detect cysts down to 0.5cm.

A definitive diagnosis can be made with genetic testing, but this is usually reserved for atypical cases (e.g. early severe disease, no family history) and up to 8% will not have an identified mutation (current genetic testing not sensitive to detect all mutation types).

Screening

Patients with a family history of ADPKD should be identified and offered screening. This involves investigating asymptomatic patients.

Ultrasound is main investigation used in screening. If ultrasound is equivocal, MRI can be used. Screening usually begins in adulthood.

Ultrasound appearance of polycystic kidney

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons

Ultrasonographic diagnostic criteria

If positive family history

- < 30 years: ≥3 cysts (unilateral or bilateral)

- 30-39 years: ≥3 cysts (unilateral or bilateral)

- 40-59 years: ≥2 cysts in each kidney

These are all associated with a positive predictive value of 100% (odds of having the disease if you have a positive result).

If no family history is present, there is no established imaging based criteria. Generally, a diagnosis can be made in the presence of multiple bilateral renal cysts (e.g. ≥10 and ≥5mm in size) or bilateral renal enlargement with cysts. Diagnosis in this context is supported by presence of hepatic cysts.

Differential diagnosis

Several conditions may lead to cystic kidneys, which need to be excluded as part of the work-up.

- Multiple benign cysts: cysts more common as we age

- Localised cystic benign: unilateral disease

- Acquired renal cystic disease: may be seen in patients with CKD on dialysis

- Medullary sponge kidney: congenital disorder of collecting ducts and calyceal system

- Other genetic conditions: e.g. autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, tuberous sclerosis, others

Investigations

Investigations are generally reserved for disease monitoring, extra-renal manifestations or complications.

Bedside

- Protein:creatinine ratio (ACR)

- Urinalysis and MC&S: infection or haemorrhage

Bloods

- Full blood count: anaemia if CKD or haemorrhagic cysts

- Urea & electrolytes: assessment of renal function

- Liver function tests: any hepatic impairment from cysts

- Bone profile: calcium/phosphate handling in CKD

- CRP: infected cysts

Imaging

- Ultrasound: principle investigations, especially in screening

- CT KUB: if presenting with suspected renal stone

- Renal MRI/CT: high sensitivity and good for assessing progression (e.g. kidney size). Useful if concern regarding renal cell carcinoma (RCC)

- Cerebral imaging (e.g. MRA): screening for cerebral aneurysms

Abdominal CT showing polycystic kidneys

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons

Special

- Genetic testing: usually reserved for atypical cases

Management

The key part of management is monitoring patients for disease progression.

The core aspect of ADPKD management is good blood pressure control and disease monitoring. Acute complications may develop that need management and as the disease progresses patients need input for CKD +/- transplant consideration.

- General treatment: blood pressure control essential (<130/80 mmHg). Slows disease progression. ACE inhibitors most effective. Regular follow-up including renal function assessment and ultrasound to look for progression. Maintain adequate hydration (3+ litres/day) unless significant CKD and dietary sodium restriction.

- Treatment for high-risk patients: vasopressin (V2) receptor antagonists may be used in patients high-risk of progression. Specialist area with specific indications. At risk of hypernatraemia.

- Managing complications: treat urinary tract infections and infected cysts. Analgesia for abdominal pain or cyst rupture (avoid NSAIDs). Rarely, cyst decompression and/or nephrectomy may be needed if recurrent infections or pain that significantly impacts on quality of life. Haematuria managed conservatively where possible. If concerns, needs work-up for RCC.

- CKD +/- transplant: manage according to CKD guidelines. For more information see our notes on chronic kidney disease.

Aneurysm screening

Screening for cerebral aneurysms is generally reserved for patients with a personal or family history of intracerebral haemorrhage, patients who require anticoagulation (e.g. develop deep vein thrombosis), patients with high-risk occupations or patients needing major surgery (e.g. renal transplant).

MR angiography is the principle imaging tool (CT angiography if MRI contraindicated). Patients with small aneurysms may have sequential screening 2-3 yearly and those with no aneurysm 5-yearly.

Indications for intervention on asymptomatic aneurysms is completed on a case-by-case basis, which depends on aneurysm size, aneurysm location, and family history. Most common treatments are endovascular coiling or surgical clipping.

All patients should be advised:

- Good BP control

- Smoking cessation

- Reduce alcohol

- No elicit drugs

- Avoid excessive straining

Complications

Patients with ADPKD are at risk of progressive renal impairment.

The spectrum of disease is variable among patients with ADPKD. Major risk factors for progressive disease include PKD1 mutation, large kidneys, recurrent visible haematuria, frequency kidney infections, Afro-Caribbean ancestry, hypertension, male gender.

Complications include:

- ESRD

- Massive cyst haemorrhage

- Cerebral haemorrhage (e.g. aneurysm rupture)

- Sepsis

- Progressive liver disease

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback