Pleural effusions

Notes

Overview

A pleural effusion refers to an abnormal collection of fluid within the pleural space.

A pleural effusion is the most common manifestation of pleural disease and it may occur from a wide range of aetiologies. It refers to an abnormal collection of fluid within the pleural space.

Pleural effusions are most commonly detected on chest x-ray. They are seen as blunting of the costophrenic angle (where the diaphragm meets the ribs). This may progress to form a dense white area with a meniscus (curve formed by the upper layer of fluid).

Large right-sided pleural effusion

Pleural effusion is a broad term for all types of fluid within the pleural space. Other terms may be used depending on the constituent of the fluid:

- Haemothorax: blood

- Hydrothorax: simple fluid

- Chylothorax: lymph

- Pyothorax (empyema): purulent inflammatory content (i.e. pus)

- Hydropneumothorax: air and fluid

Anatomy & physiology

The pleura are serous membranes that line the lungs and thoracic cavity.

The pleura are serous membranes that fold back on themselves to form a membranous pleural sac with two layers and a potential space known as the pleural space. They are formed of a surface epithelium of mesothelial cells and underlying connective tissue. The three key layers of the pleura are:

- Parietal pleura: outer layer. Attaches to the chest wall

- Pleural space: potential space. Contains ~10 mL of fluid that is constantly turned over each day

- Visceral pleura: inner layer. Covers the lungs, blood vessels and bronchi

The pleural fluid has two major functions:

- Lubricates the pleural surfaces: easier for the layers to slide over one another during respiration

- Generates surface tension: pulls the two layers (parietal and visceral) adjacent to one another

Pleural recess

This refers to two areas where adjacent areas of parietal pleura come into contact because the pleural space is not totally filled by lung tissue. These areas are where fluid may accumulate in pleural effusions.

- Costomediastinal recess: between the mediastinum and costal pleura

- Costodiaphragmatic recess: between the diaphragm and costal pleura

Pathophysiology

Under normal conditions, there is a constant balance between fluid entry and exit within the pleural space.

Several factors contribute to the balance between fluid entry and fluid exit in the pleural space. This occurs locally within the parietal and visceral pleural capillaries:

- Hydrostatic pressure: pressure exerted by a fluid against a membrane, Increases lead to fluid leaking from blood vessels

- Oncotic pressure: osmotic pressure produced by large macromolecules (e.g. proteins). Exerts a ‘pulling power’ on fluid

- Lymphatic drainage: drains body fluid and returns it to the systemic circulation. Can alter the hydrostatic pressure

These factors are connected by Starling’s equation that describes the net flow of fluid across a semipermeable membrane and considered 'Starling forces'. It is the balance between these driving forces that leads to the formation of a pleural effusion.

Increased fluid entry

Fluid may enter the pleural space due to several factors:

- Increased vasculature permeability (e.g. infection, malignancy): loss of fluid and macromolecules from 'leaky' vessels

- Increased microvascular pressure (e.g. heart failure): increased venous pressure affects hydrostatic pressure forcing fluid out

- Decreased plasma oncotic pressure (e.g. nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis): favours accumulation of fluid in the pleural space due to hypoproteinaemia

Decreased fluid exit

Reduced clearance of fluid is predominantly due to alteration in lymphatic drainage. Various factors affect lymphatic drainage, but the underlying physiology is poorly understood:

- Intrinsic factors: inflammatory mediators, infiltration (e.g. cancer), damage (e.g. radiotherapy)

- Extrinsic factors: physical compression, limitation by respiratory motion, decreased intrapleural pressure

Aetiology

The causes of a pleural effusion can be broadly divided into transudates and exudates.

Specific causes of pleural effusion (e.g. haemothorax) usually have a clear cause (e.g. trauma). When referring to a simple pleural effusion (i.e. hydrothorax) the causes can be broadly divided into transudates and exudates.

Transudate

A transudate is a fluid with minimal protein or cellular content. It occurs due to alteration in hydrostatic and oncotic pressures leading to the fluid being ‘squeezed’ into the pleural space (ultrafiltration).

- Heart failure

- Hypoalbuminaemia

- Cirrhosis

- Constrictive pericarditis

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Peritoneal dialysis

- Meigs' syndrome (Ascites and pleural effusion in association with a benign ovarian tumour).

Exudate

An exudate is a fluid with a high protein and cellular content. It develops due to a variety of inflammatory conditions that affect vessel permeability and/or lymphatic drainage. Exudates are commonly due to infection or malignancy.

- Parapneumonic effusion (secondary to pneumonia)

- Malignancy (commonly breast or lung)

- Tuberculosis

- Pulmonary embolism

- Pancreatitis

- Radiation pleuritis

- Systemic inflammatory condition (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis)

- Trauma

Clinical features

On examination, a pleural effusion is characterised by reduced breath sounds, stony dull percussion and reduced vocal resonance.

Symptoms

- Breathlessness

- Non-productive cough

- Pleuritic pain

- Extra-pulmonary symptoms: depends on the underlying cause (e.g. weight loss in malignancy or fever in infection)

Signs

Clinical signs usually develop when a pleural effusion is >300 mL. Signs are localised to the side of the effusion.

- Reduced chest expansion

- Reduced breath sounds

- Stony dull percussion

- Reduced vocal resonance: auscultate the chest and ask the patient to speak.

- Trachea deviation (away from the side of effusion): if large effusion (>1000 mL)

- Extra-pulmonary signs: depends on the underlying cause (e.g. finger clubbing in lung cancer)

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a pleural effusion is easily confirmed by chest x-ray.

A formal diagnosis of a pleural effusion can be confirmed with a standard posteroanterior (PA) chest x-ray. Approximately 200 mL of pleural fluid is needed to detect a pleural effusion on PA chest x-ray.

Left-sided pleural effusion

Other imaging modalities

Ultrasound can be used to detect pleural effusions with high sensitivity. Ultrasound should be used to guide pleural aspiration. CT and MRI will also show pleural effusions. CT should be performed when a malignancy or pulmonary lesion is suspected.

Investigations

The principal investigation for assessment of a pleural effusion is pleural paracentesis and analysis.

Transudate versus exudate

Pleural effusions can be categorised into transudates or exudates based on their protein content. The broad cut-off is around 30 g/L. This is based on the interpretation of pleural fluid following aspiration (discussed further below).

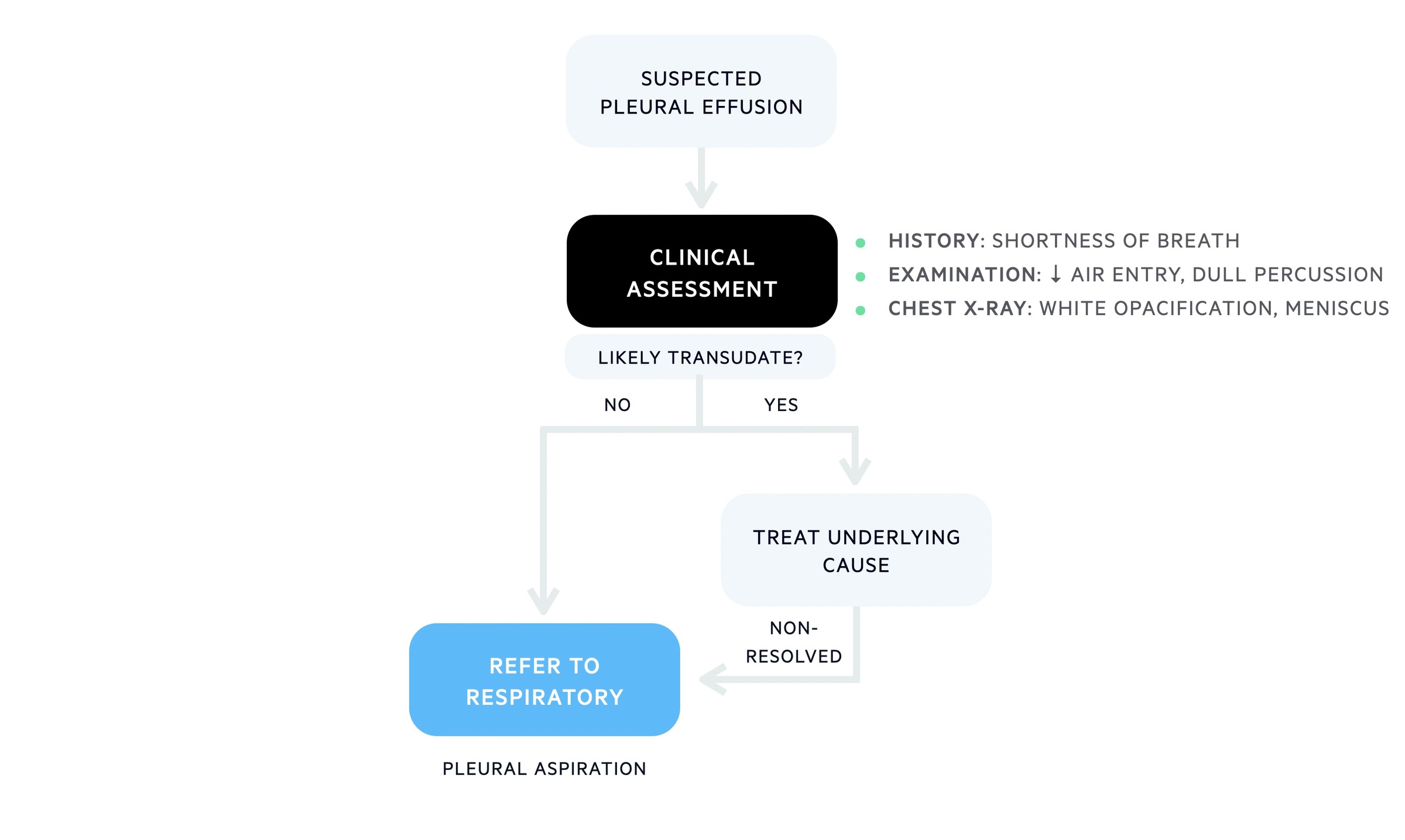

In general, if the cause is suspected to be a transudate (e.g. heart failure), treatment is guided towards the underlying cause. This is very common for bilateral pleural effusions. If in doubt, pleural aspiration and analysis are needed. If the cause is suspected to be an exudate (e.g. infection) that is more commonly seen in unilateral effusions, further investigations including pleural aspiration are needed.

Unilateral pleural effusion

A unilateral pleural effusion usually requires further investigations into the possible cause. This includes ‘tapping’ the effusion that refers to performing a pleural paracentesis. The pleural fluid can then be analysed to confirm an exudate and to help determine the cause. Other tests may be warranted depending on the results and suspected diagnosis.

The British Thoracic Society produced pleural guidelines detailing the appropriate diagnostic algorithm for a unilateral pleural effusion, which is simplified below:

Initial workup for a unilateral pleural effusion

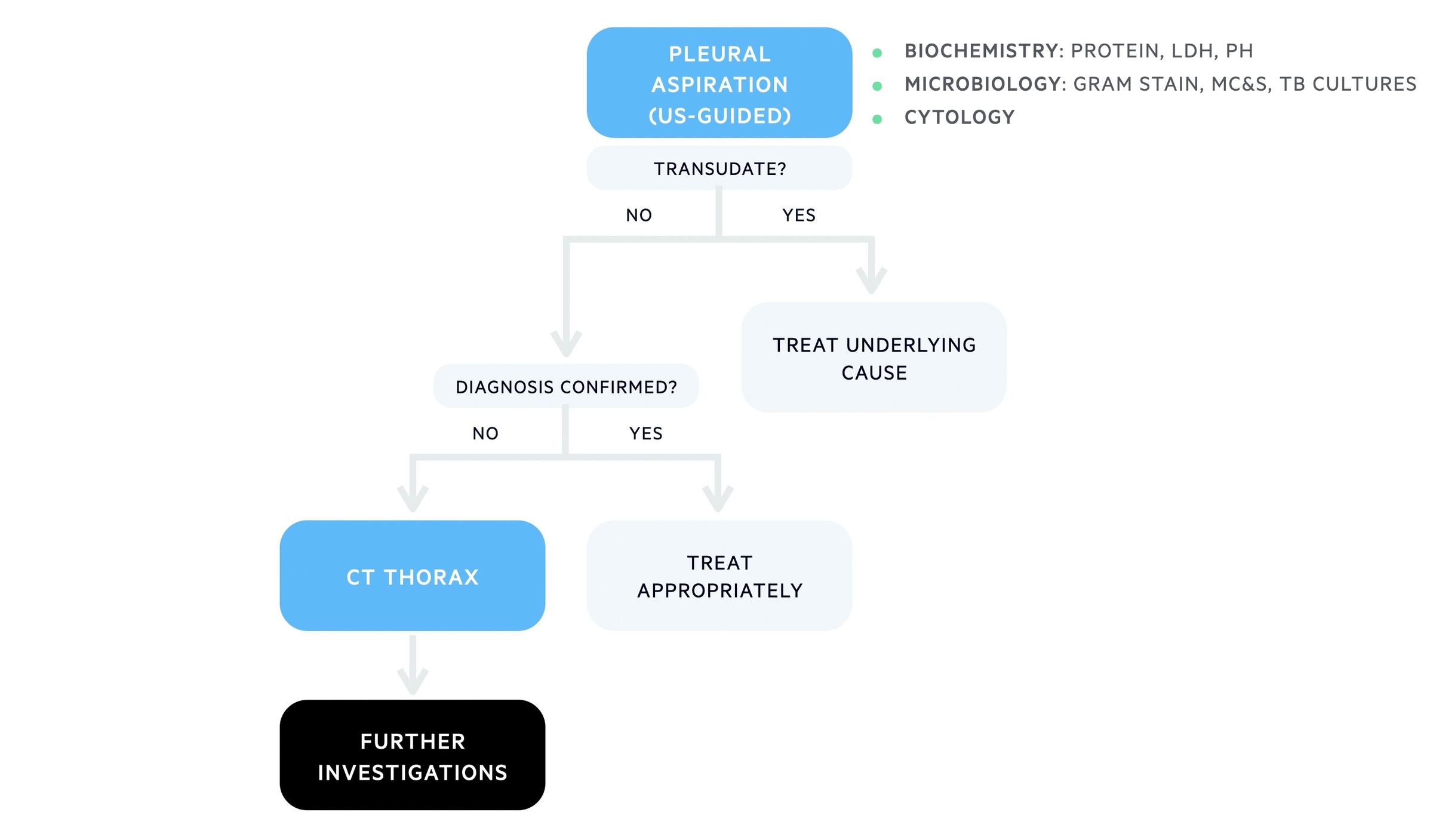

Referral to respiratory +/- pleural aspiration for all exudates

Following identification of a suspected exudative unilateral pleural effusion patients should be referred to respiratory for further investigation. The respiratory team can help with pleural aspiration and further investigations depending on the suspected aetiology.

Diagnostic algorithm for unilateral effusion

Low threshold for cross-sectional imaging (e.g. CT) if unknown cause or cancer suspected

Bilateral pleural effusions

In general, pleural paracentesis is not performed in patients with bilateral pleural effusions where the cause is strongly suspected to be a transudate (e.g. heart failure). Investigations (e.g. ECHO, BNP) and treatment (e.g. diuretics) should be directed towards the underlying cause. If the aetiology is in doubt, then pleural aspiration can be considered.

Pleural paracentesis

This involves inserting a small needle into the pleural cavity under ultrasound guidance to remove a sample of fluid for further analysis. It can be completed as a simple diagnostic test removing a small amount of fluid (e.g. 20 mL) or completed as part of a theurapeutic pleural aspiration removing several 1-1.5 L of fluid for symptomatic relief.

Interpreting pleural fluid

Analysis of pleural fluid helps determine whether it is a transudate or exudate.

Pleural effusions can be categorised into a transudate or exudate:

- Transudate: an extravascular fluid with low protein content (< 30 g/L)

- Exudate: an extravascular fluid with high protein content (> 30 g/L)

Sometimes it is difficult to differentiate between transudates and exudates when the protein count is close to 30 g/L. In these situations, we apply Lights criteria, which is discussed below.

The basic tests that should be completed on all pleural samples include pH, protein count, LDH, MC&S, and cytology. Additional tests can be completed depending on the suspected aetiology. The list of pleural tests are shown below:

- pH

- Gram stain

- Microscopy, culture, and sensitivity (MC&S)

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

- Protein

- TB investigations (e.g. MC&S, PCR, acid-fast bacilli)

- Cytology

- Lipid testing: cholesterol, triglycerides

- Glucose

- Amylase

- Haematocrit

- Nucleated cell count

For more information on these tests and their interpretation see pleural fluid notes.

Lights criteria

Pleural effusions can be categorised into transudates or exudates based on their protein content. The broad cut-off is ~30 g/L. However, when the level of protein is close to 30 g/L (~25-35 g/L), Lights criteria can be applied to formally determine whether it is a transudate or exudate. This is critical to narrow the differential diagnosis and guide further investigations. To apply Lights criteria, the total protein and LDH level should be measured in both the pleural fluid and serum.

Pleural fluid is an exudate if one or more of the following criteria are met:

- Pleural fluid protein divided by serum protein is > 0.5

- Pleural fluid LDH divided by serum LDH is >0.6

- Pleural fluid LDH >2/3 the upper limits of laboratory normal value for serum LDH

Management

Pleural effusions can be drained for symptomatic relief, but treatment should be directed towards the underlying cause.

The management of a pleural effusion is dependent on size, whether the patient is symptomatic and the suspected underlying cause (e.g. heart failure or cancer). We briefly mention some of the key aspects of management that include:

- Address underlying cause

- Pleural aspiration and/or chest drains

- Pleurodesis

- Surgical intervention

Address underlying cause

The underlying cause of the pleural effusion should be sought and treated. If the pleural effusion is a transudate then aspiration should be avoided. A typical example is congestive cardiac failure. Pleural effusions are common and management involves diuretics to remove excess fluid.

If an infection is suspected then patients require antibiotics. If malignancy is suspected then patients require a full work-up to determine the primary and the case will be discussed in a multidisciplinary meeting to determine ongoing treatment options.

Pleural aspiration and/or chest drains

The decision to drain a pleural effusion depends on multiple factors:

- Size

- Symptoms: asymptomatic or symptomatic

- Transudate or exudate

- Aetiology

- Recurrent/resistant episodes

In general, patients with small or asymptomatic pleural effusions do not need drainage. Patients with large or symptomatic effusions can undergo pleural intervention to drain the effusion. The two principal options are:

- Therapeutic paracentesis: this involves the removal of 1-1.5 L of pleural fluid via a special drainage kit that can then be removed at the end of paracentesis.

- Chest drain insertion: this involves the insertion of a tube (10-14 Fr) into the pleural space to allow drainage over hours to days. Drains are connected to an underwater seal to prevent backflow of air or fluid into the pleural space.

NOTE: occasionally, long-term indwelling drains may be used for recurrent pleural effusions. This is an alternative to pleurodesis.

Both procedures should be completed with US guidance and patients should be monitored for complications, which can include:

- Re-expansion pulmonary oedema: this refers to the development of pulmonary oedema on re-expansion of the lung. To reduce the risk patients should be monitored for symptoms and drainage limited to 1-1.5 L at any time. If symptoms develop at a lower drainage volume, the drain can be clamped and patients reassessed before continuation.

- Pneumothorax: patients may have a post-procedure pneumothorax due to iatrogenic lung puncture or inadvertent introduction of air

- Infection: a complicated parapneumonic pleural effusion may develop from poor sterile technique

- Bleeding

- Damage to thoracic viscera

- Subcutaneous emphysema

Pleurodesis

Pleurodesis is a procedure to obliterate the pleural space and prevent re-accumulation of fluid or air. It involves inducing pleural inflammation and fibrosis with a chemical sclerosant or by manual abrasion. This may be an option for patients with recurrent pleural effusions or patients with malignant pleural effusion that is likely to re-accumulate after drainage.

Surgical intervention

Surgery may be needed in patients with pleural effusion to aid the diagnosis (e.g. need for biopsy) or to treat the underlying effusion. Surgical intervention is common via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) that is a minimally invasive surgical technique that enables a number of surgical procedures (e.g. pleural biopsy, pleural wash-out and decortication, pleurectomy).

Parapneumonic effusion

A pleural effusion secondary to adjacent pneumonia is known as a parapneumonic effusion.

A parapneumonic effusion is commonly seen in the setting of pneumonia (infection/inflammation in the alveoli). It can be categorised according to the severity of the effusion and whether the pleural fluid has become infected.

- Uncomplicated (simple) effusion: reactive effusion. Fluid is sterile

- Complicated effusion: fluid has become infected with a microorganism

- Empyema: a collection of pus within the pleural space. Patients are very unwell and need urgent drainage

NOTE: a complex parapneumonic effusion refers to one that has internal loculations known as septa that separate the effusion into different pockets making it difficult to drain.

Any patient with a suspected parapneumonic effusion requires prompt antibiotic therapy according to local hospital guidelines. The decision to drain the effusion depends on the type, size, and complexity. Simple parapneumonic effusions can usually be managed with antibiotics alone to treat pneumonia and drainage is not required. If a complicated effusion or empyema is suspected then drainage as soon as possible is recommended.

Last updated: October 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback