Abdominal pain

Notes

Overview

Abdominal pain is a very common presenting symptom.

Abdominal pain is a very common presenting complaint. It can be difficult to comprehend due to the shear volume of conditions that can present with this symptom. The job of any junior doctor, physician associate or advanced nurse practitioner is to take a good history, performance a solid examination and then come up with a synthesised list of possible diagnoses (i.e. the differential diagnosis).

Two of the most important things to uncover from the history is the ‘timing of onset’ and the ‘location’. This is because these two factors really help narrow down the diagnosis.

- Timing of onset: acute, subacute, chronic

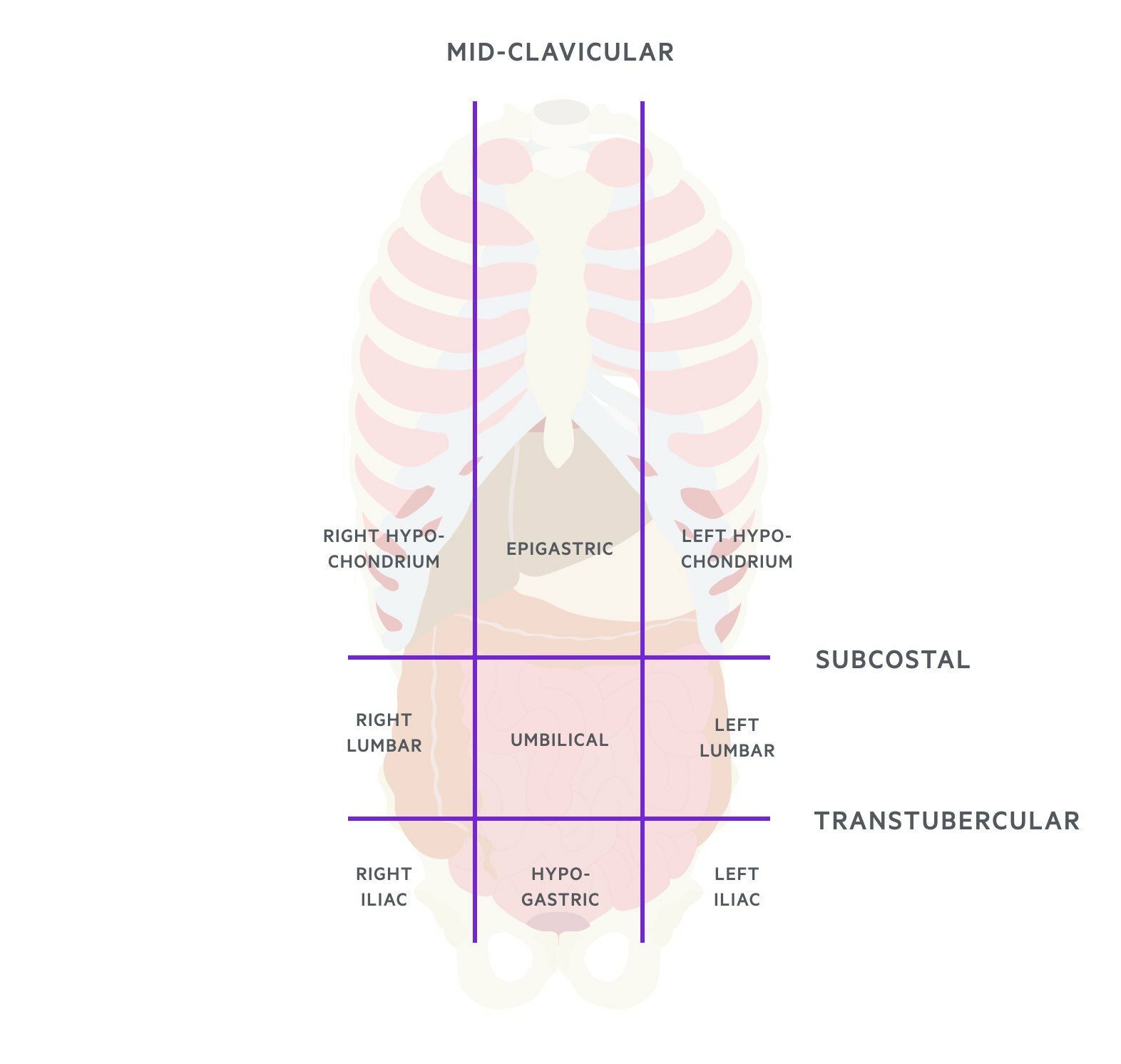

- Location: based on the nine regions of the abdomen

REMEMBER: The acute abdomen is a very important clinical presentation because it includes a number of life-threatening conditions that may require urgent surgical management.

Differential diagnosis

The differential for abdominal pain can be organised into organ systems.

We can consider the diagnosis of abdominal pain by organ system. We can then further narrow the differential diagnosis based on the location of pain and onset of symptoms. The major categories include:

- Gastrointestinal

- Renal and urinary system

- Gynaecological

- Vascular

- Other

Gastrointestinal

A common cause of acute abdominal pain. Gastrointestinal causes can range from common relatively benign pathologies (e.g. gastroenteritis) to life-threatening (e.g. perforation).

Gastrointestinal causes can be further divided based on location and/or organ system affected.

- Gastroduodenal: peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, gastric cancer, GORD

- Intestinal: appendicitis, diverticulitis, gastroenteritis, strangulated hernia, Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, volvulus, intussusception, mesenteric adenitis, bowel ischaemia

- Hepatobiliary: cholecystitis, cholangitis, biliary colic, hepatitis, hepatic abscess, hepatic congestion (e.g. heart failure)

- Pancreatitis: acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer

Renal and urinary system

Acute cystitis (i.e. urinary tract infection) is an extremely common cause for abdominal pain in females. Renal colic is another common cause of abdominal pain presenting with the classical loin-to-groin pain.

- Cystitis

- Pyelonephritis

- Ureteric/renal colic

- Hydronephrosis

- Malignancy

- Acute urinary retention

- Polycystic kidney disease

Gynaecological

Gynaecological diagnoses should always be considered in female patients. As a general rule, pregnancy-related complications (i.e. ectopic pregnancy) always need to be excluded in pre-menopausal females by performing a pregnancy test.

- Ruptured ectopic pregnancy

- Ovarian torsion

- Ovarian cyst rupture

- Salpingitis

- Endometriosis

- Mittelschmerz

- Red degeneration of fibroid

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

Vascular

Vascular causes are less common, but you need to have a high index of suspicion, especially in elderly patients or those with other cardiovascular disease (e.g. ischaemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease).

Be wary of the elderly patient presenting with ‘loin-to-groin’ pain. If often suggests aortic dissection.

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Ischaemic colitis

- Aortic dissection

Other

Other causes can include problems with the abdominal wall, retroperitoneal space, spleen, pain referred from another area (i.e. myocardial infarction) or abdominal pain associated with traditionally ‘medical’ diagnoses.

- Abdominal wall: Rectus sheath haematoma

- Retroperitoneal space: psoas abscess, retroperitoneal haemorrhage

- Spleen: splenic abscess, splenic infarction

- Thorax: thoracic spine disease, shingles

- Referred pain: testicular torsion, pericarditis, ACS, lower lob pneumonia, pulmonary embolism

- Other medical diagnoses: sickle cell crisis, adrenal insufficiency

History

The history is critical to help differentiate between the vast number of causes of abdominal pain.

Key aspects in the history include age, gender, pain characterisation, location and associated features.

Age and gender

You should always make a note of the patients’ age and gender. Certain diagnoses are more common in one sex (e.g. cystitis more common in females) and others will only occur in patients with the relevant anatomy (e.g. testicular torsion in men or transwomen without gender reassignment surgery). Many diagnoses are more common at particular ages (e.g. vascular disease in elderly or mesenteric adenitis in children).

Pain onset

Always take a full pain history in patients with abdominal pain. This should be done using the SOCRATES mnemonic. Determine if the pain came on acutely or is chronic. Sudden acute abdominal pain is concerning for a serious underlying pathology such as testicular torsion, ruptured ectopic pregnancy or ruptured abdominal aneurysm.

Characterisation

The character of the pain may change over time and may migrate (e.g. loin-to-groin in renal colic):

- Colicky (pain comes in waves): suggest obstruction of a visceral structure (e.g. ureter, bile ducts or intestines)

- Severe pain on movement: suggestive of perforation and peritonitis

- Tearing pain: suggestive of aortic dissection or rupture

- Constant dull pain: suggests inflammation (e.g. appendicitis, diverticulitis)

- Constant sharp pain: suggestive of peritonitis that may be localised or diffuse (e.g. perforation)

Radiation

Determine whether the pain radiates anywhere and whether it has ever occurred before.

- Radiation to the back: renal, hepatobiliary and pancreatic pain

- Radiation to the groin: renal colic

- Shoulder tip pain: diaphragmatic irritation (e.g. perforation)

Location of pain

Location should be based on the nine regions of the abdomen or more broadly based on the four quadrants to keep things simple. Some examples are listed below. Note that this is not an exhaustive list and some conditions may cause pain in more than one region.

- Right upper quadrant (hypochondrium):

- Biliary: colic, cholangitis

- Hepatic: hepatitis, abscess

- Lung: right lower lobe pathology

- Epigastrium:

- Gastroduodenal: GORD, PUD, cancer

- Pancreatic: pancreatitis

- Referred pain: cardiac

- Left upper quadrant (hypochondrium):

- Spleen: abscess, infarction

- Lung: left lower lobe pathology

- Right flank:

- Renal: colic

- Vascular: aneurysm rupture or dissection

- Ovarian: cyst rupture

- Umbilicus:

- Intestinal: Appendicitis, meckel’s diverticulitis, obstruction, Crohn’s disease

- Pancreatic: pancreatitis

- Left flank:

- Renal: colic

- Vascular: aneurysm rupture or dissection

- Ovarian: cyst rupture

- Right iliac fossa:

- Intestinal: Appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease, inguinal hernia

- Gynaecological: ectopic pregnancy, endometriosis

- Urological: testicular torsion

- Suprapubic:

- Urinary: retention, cystitis

- Left iliac fossa:

- Intestinal: diverticulitis, large bowel tumour, inguinal hernia

- Gynaecological: ectopic pregnancy

- Urological: testicular torsion

Associated features

Associated features help you to support or refute the potential diagnosis.

They can help you localise the problem to a particular organ system (e.g. PV bleeding in gynaecological problems or dysuria in urinary problems) and whether there is a systemic disease process (e.g. fever, anorexia, weight loss).

Examination

This should include a full abdominal examination.

A full examination is important to look for clues to the underlying diagnosis. Pain located in a particular abdominal region supports the history findings (e.g. right upper quadrant pain associated with pain on palpation in this area).

Look for signs of peritonitis:

- Rigid abdomen

- Percussion tenderness

- Haemodynamic instability (tachycardia, hypotension)

Bowel sounds are helpful in suspected obstruction:

- High pitched (tinkling): obstruction

- Absent: ileus (non-mechanical obstruction)

It is important to consider a digital rectal examination, especially if there is concern regarding bowel obstruction or gastrointestinal bleeding, and assessment of the hernial orifices.

Investigations

Simple bedside investigations can provide a lot of insight into the possible diagnosis.

We always break investigations down into different components to make it easier to understand and remember. These categories are known as:

- Bedside tests

- Blood tests

- Imaging

- Special tests

Bedside tests

Simple bedside investigations are crucial in patients with acute abdominal pain to help exclude certain causes and to assess how unwell a patient may be.

- Observations: to exclude haemodynamic instability and sepsis

- Urine dip: to exclude urinary tract infection. Haematuria may be seen in renal colic

- ECG: to exclude a cardiac cause

- Pregnancy test: to exclude pregnancy-related complications (e.g. ectopic)

Blood tests

A series of basic blood tests including a venous blood gas should be requested in all patients. More specific blood tests depend on the suspected cause.

- Venous blood gas: gives a snap-shot biochemical assessment of the patient. Lactate is very important, which is a marker of peripheral tissue ischaemia (i.e. if raised is a sign of shock).

- Full blood count: look at the white cells (high counts suggests inflammatory response) and haemoglobin (acute drop suggests bleeding)

- Urea & electrolytes: useful in suspected urinary tract pathologies and to look for complications (e.g. acute kidney injury)

- Liver function tests: useful to investigate causes of right upper quadrant pain

- C-reactive protein: elevated in inflammatory or infective causes

- Group & save: especially if considering a bleeding aetiology or surgical management

- Coagulation: especially prior to surgery (if deranged may need correcting)

Imaging

A significant proportion of patients with acute abdominal pain presenting to accident & emergency will undergo cross-sectional imaging with computed tomography (CT). Ultrasound may be preferable in young or pregnant patients depending on the indication. MRIs are usually requested on the background of prior imaging to provide further detail (e.g. MRCP).

Plain film radiographs still have a role in practice.

- Erect chest x-ray: to look for free air under the diaphragm that suggests perforation of a hollow abdominal viscus. Largely replaced by CT.

- PA chest x-ray: look for lower lobe pneumonia

- Abdominal x-ray: can look for signs of bowel obstruction, volvulus or even bowel wall thickening (e.g. colitis)

Special tests

More specialist investigations depend on the cause. They may include:

- Endoscopy: gastroscopy, colonoscopy

- Diagnostic laparoscopy: a low-risk and minimally invasive procedure to examine the inside of the abdomen

Key tip

It is important you understand the concept of peritonitis and how to assess this during you clinical examination.

When a patient presents with acute abdominal pain it is important to exclude an ‘acute abdomen’. An 'acute abdomen’ generally refers to the presence of peritonitis or patients who are at risk of developing acute peritonitis.

Peritonitis refers to inflammation of the peritoneum, which is the lining of the abdomen. Inflammation of the lining of the peritoneum can be localised causing a specific location of pain (e.g. appendicitis right iliac fossa) or can be generalised (e.g. perforated viscera). Generalised peritonitis usually occurs following perforation of bowel. Perforation leads to a small hole within the gastrointestinal system, which allows faeces and bacteria to enter the sterile peritoneal lining causing marked inflammation and pain. Perforation is the main sequelae of many gastrointestinal pathologies and a surgical emergency.

Patients with peritonitis will be rigid and refusing to move. This is because movement leads to irritation of the lining of the peritoneum and severe pain. Palpation of the abdomen of a patient with peritonitis will be extremely tender even to light touch with percussion tenderness noted (pain on light percussion over one or more of the four quadrants).

Last updated: July 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback