Cervical cancer

Notes

Overview

Cervical cancer is a common malignancy whose aetiology is intimately related to human papillomavirus.

In the UK it is the most common cancer in women younger than 35. In the developing world cervical cancer is the second most common cancer in women. It can occur in women, transgender men (with retained cervix) and non-binary individuals (assigned female at birth).

Cervical screening can help to prevent cervical cancer by diagnosing and treating pre-malignant lesions. Unfortunately, attendance to screening fluctuates and has been falling recently prompting a number of national campaigns to combat this.

Epidemiology

There are around 3,200 cases of cervical cancer in the UK each year.

In 2017, cervical cancer accounted for 2% of cancers and was the 14th most common cancer in women. In 2015 - 2017, the incidence was highest in women aged 30 - 34.

It is projected that the incidence will decrease in the coming decades as a result of the HPV vaccines.

Figures from Cancer Research UK.

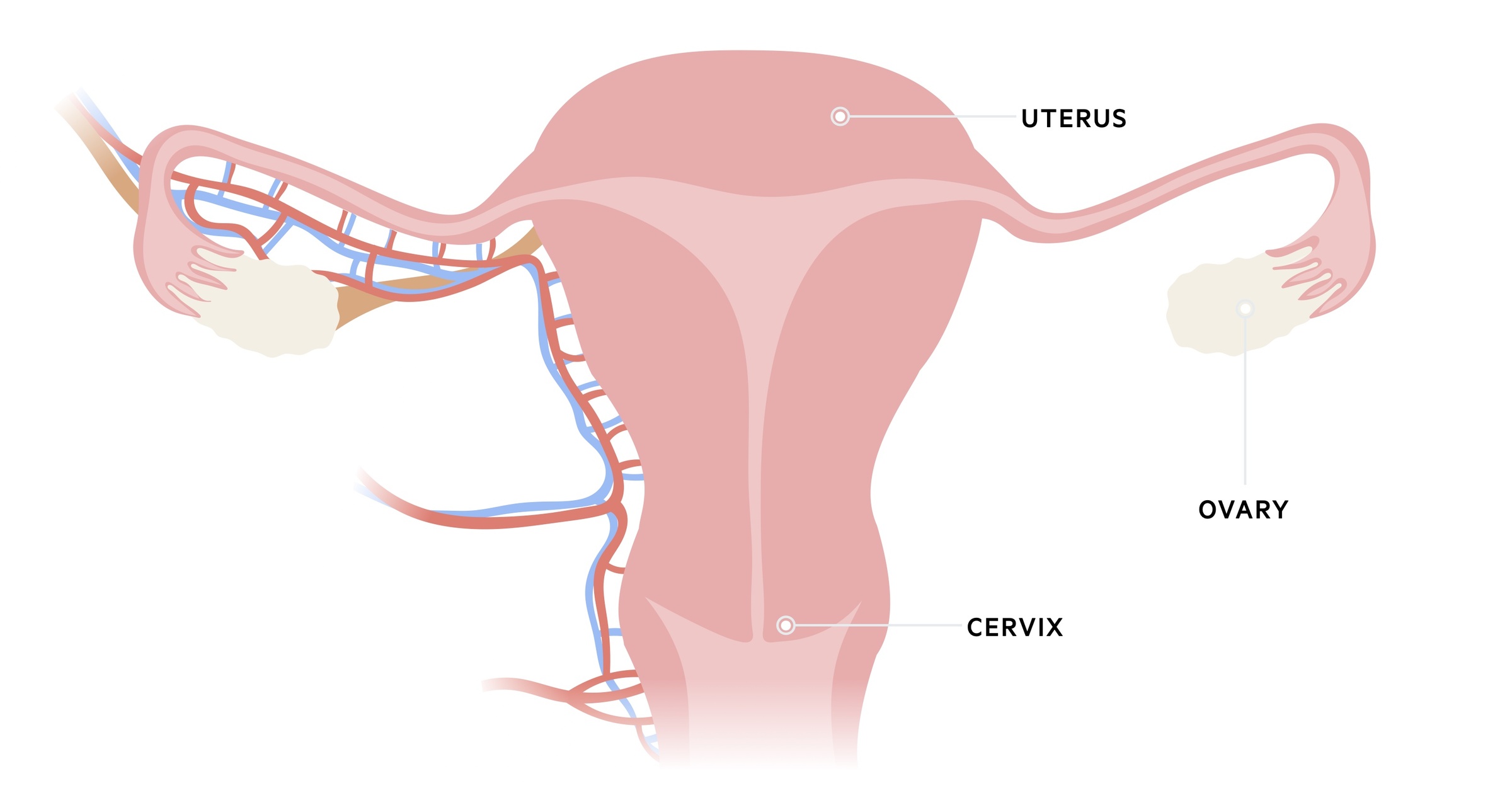

The cervix

The cervix, derived from the Latin cervix meaning neck, is a fibromuscular structure that sits at the lower portion of the uterus.

It has an external os, continuous with the vaginal canal, and an internal os continuous with the uterine cavity. Between the two os lies the endocervical canal which is lined by simple columnar epithelium. The ectocervix is the vaginal canal facing portion of the cervix and is lined by stratified squamous non-keratinised epithelium.

The interface between the columnar and squamous epithelium is called the squamocolumnar junction. The exact position of this varies depending on age, menstrual status, pregnancy status and other factors (e.g. hormonal contraceptives).

Ectropion refers to the eversion of endocervical columnar epithelium onto the ectocervix. This is a normal physiological process that occurs at different stages of life (e.g. post menarche, during pregnancy). The replacement of this newly formed columnar epithelium with squamous epithelium is referred to as squamous metaplasia. Again, this is a normal physiological process. The region where this occurs is called the transformation zone - this is the zone in which most cervical cancers arise.

HPV

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is implicated in the development of approximately 99.7% of cervical cancers.

HPV is a common virus that is normally sexually transmitted. It is estimated that 50-80% of sexually active women will have an HPV infection in their lifetime. Around 40% will be infected in the first two years of being sexually active.

There are more than 100 types though less than 20 have been strongly linked to cervical cancer (so-called high-risk HPV). The two most important subtypes are HPV 16 and 18 - they are responsible for 70-75% of cervical cancers.

The majority of infections are asymptomatic and resolve spontaneously. However, they may lead to oncogenic changes and cervical cancer. Vaccination against certain subtypes of HPV is now fundamental to the prevention of cervical cancer (see the Prevention chapter below for more detail.)

Non-cancer-causing strains (or at least the evidence associating them with cancer is limited) HPV 6 and 11 are responsible for genital warts.

Risk factors

Certain risk factors increase the risk of cervical cancer in those with HPV infections.

- Missed screening

- Smoking

- High parity (number of births at full term > 5)

- Family history

- Combined oral contraceptive

- Immunosuppression (e.g HIV/AIDS)

In daughters of women treated with diethylstilbestrol (DES), there is an increased risk of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix. DES was a synthetic oestrogen used from the 1940s to the 1970s to prevent premature labour and miscarriage and was later found to be associated with cervical cancer.

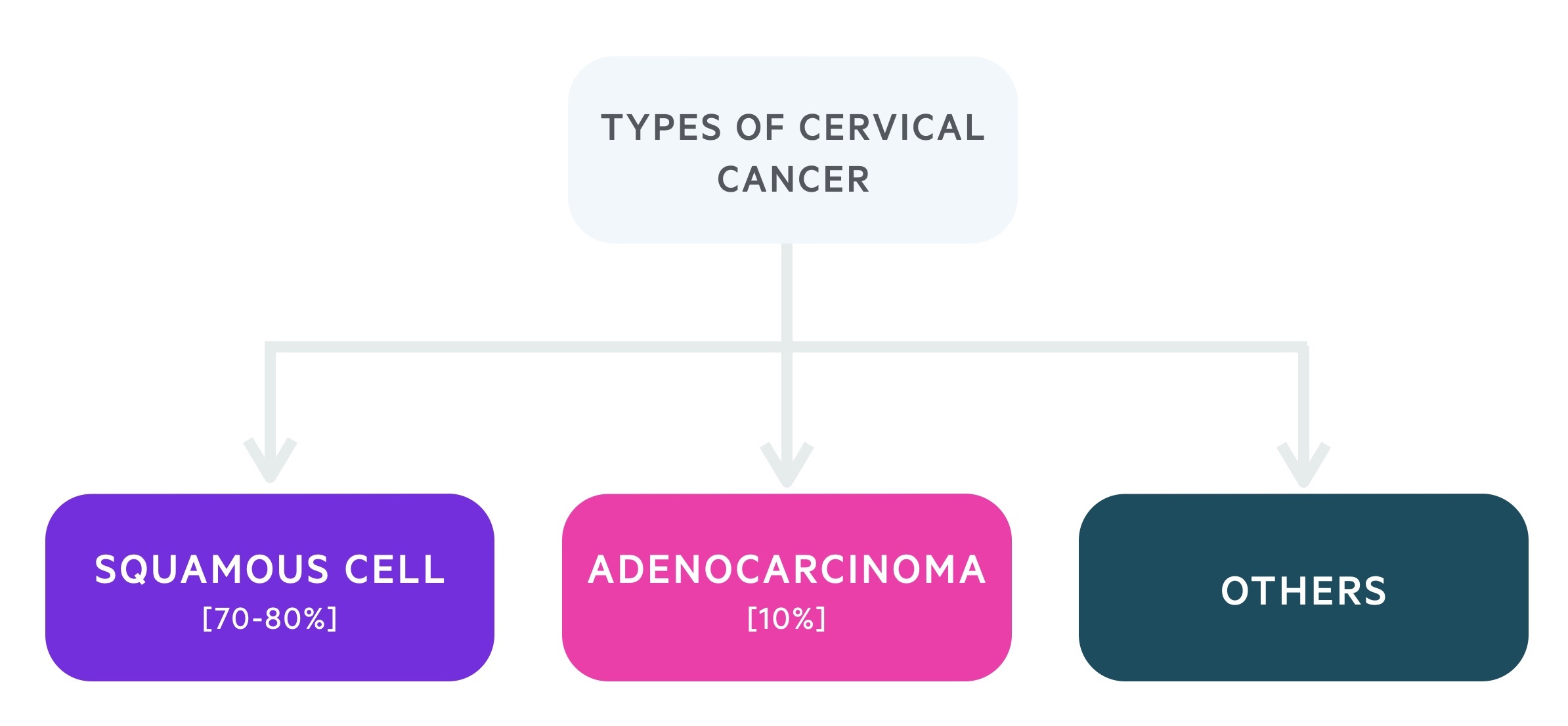

Types

The most common type of cervical cancer is squamous cell carcinoma.

Around 70-80% of cervical cancers are squamous cell carcinomas. The second most frequent cell type is adenocarcinoma, responsible for around 10% of cases. Other rarer causes include small cell cancer and lymphoma.

Adenocarcinomas tend to develop within the endocervical canal and are often diagnosed at more advanced stages.

Clinical features

Patients can be asymptomatic or present with features including intermenstrual bleeding and postcoital bleeding.

Patients may be asymptomatic and picked up during routine screening. Others develop features similar to those seen in other gynaecological malignancies and infections. These include:

- Intermenstrual bleeding

- Post-coital bleeding (vaginal bleeding after sex)

- Post-menopausal bleeding

- Malodorous discharge

- Blood-stained discharge

- Pelvic pain

- Dyspareunia (pain during sex)

On examination, a malignant appearing cervical lesion may be apparent. On occasion patients will present with features of advanced disease - this can include fistulisation to surrounding structures including the bladder and bowel.

Referral

Women with suspected cervical cancer should be referred on an urgent (two-week wait) suspected cancer pathway.

The cervical cancer screening programme is the most common referral pathway. For more information on routine screening, see our note on Cervical cancer screening.

In addition NICE NG 12: Suspected cancer: recognition and referral advise urgent (two-week wait) referral if on examination the appearances of the cervix are concerning for cancer.

Symptoms of cervical cancer are non-specific and often similar to other gynaecological malignancies. Additional prompts for referral include:

- Unexplained cervical symptoms (including discharge)

- Postmenopausal bleeding:

- If not on hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

- Persistent/unexplained bleeding 6 weeks after stopping HRT

- Persistent premenopausal bleeding (intermenstrual or post-coital) or blood-stained vaginal discharge and:

- Polyp, ectropion, cervicitis, or warts and any infection treated

- Persistent intermenstrual bleeding

Other reasons for referral include patients with suggestive features who have not attended screening, have bleeding > 3 months, change in symptoms/bleeding pattern or failure of contraception to regulate bleeding.

Investigations

Colposcopy +/- biopsy is the key investigation in the diagnosis of cervical cancer.

Bloods

- FBC

- UE

- LFT

Colposcopy

Colposcopy allows optimal and magnified visualisation of the cervix and for biopsies to be taken.

Imaging

CT, MRI and PET may all be used to assess disease burden and spread.

FIGO staging

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system is commonly used to stage cervical cancer.

Stage 1

IA: Invasive carcinoma diagnosed only by microscopy, with maximum depth of invasion <5mm

- IA1: Measured stromal invasion <3 mm in depth

- IA2: Measured stromal invasion >/=3 mm and <5 mm in depth

IB: Invasive carcinoma with measured deepest invasion >/= 5 mm(greater than Stage IA), lesion limited to the cervix uteri

- IB1: Invasive carcinoma >/= 5 mm depth of stromal invasion, and <2 cm in greatest dimension

- IB2: Invasive carcinoma >/= 2 cm and < 4 cm in greatest dimension

- IB3: Invasive carcinoma >/= 4 cm in greatest dimension

Stage 2

IIA: Involvement limited to the upper two-thirds of the vagina without parametrial involvement

- IIA1: Invasive carcinoma < 4cm in greatest dimension

- IIA2: Invasive carcinoma >/= 4 cm in greatest dimension

IIB: With parametrial involvement but not up to the pelvic wall

Stage 3

IIIA: Carcinoma involves the lower third of the vagina with no extension to the pelvic wall

IIIB: Extension to the pelvic wall and and/or causes hydronephrosis or non-functioning kidney

IIIC: Involvement of pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes, irrespective of tumour size and extent (with r and p notations)

- IIIC1: Pelvic lymph node metastasis only

- IIIC2: Para-aortic lymph node metastasis

Stage 4

IVA: Spread to adjacent pelvic organs

IVB: Spread to distant organs

Management

Management is dependent on staging and patient wishes.

The aim is to achieve cure (if possible) or prolong disease and complication-free life. Here we discuss the broad principles of management of cervical cancer. In advanced disease, palliative care input can be essential.

Stage IA1 (microinvasive disease)

Large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) or knife cone biopsy can be used. The risk of lymph node metastasis is low and lymphadenectomy is rarely warranted.

Simple hysterectomy may also be considered, particularly if preserving fertility is not an issue.

Stages IA2-IIA (early stage disease)

Stage IA2 has a risk of spread to the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes. One option for treatment is a modified radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy.

Stage IBI and stage IIA less than 4cm are often treated with radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy.

In pre-menopausal women, ovarian conservation may be discussed and fertility-sparing treatments can be considered if the patient has not completed their family. This will depend on exact staging and patient wishes.

For those with disease > 4cm, chemoradiation is the treatment of choice.

Stage IIB-IVA (locally advanced disease)

Chemoradiation tends to be the treatment of choice.

Stage IVB (metastatic disease)

Combination chemotherapy, single-agent therapy and palliative radiotherapy may all be used.

Prevention

There are three key elements in prevention; vaccination, screening and safe sex.

The combination of the HPV vaccine and the screening programme should lead to a reduction in the rates of invasive cervical cancer over the coming decades. General measures such as a healthy lifestyle and smoking cessation also reduce the risk of cervical cancer as well as other long-term health problems.

HPV Vaccine

The HPV vaccine, composed of two doses, is offered to both boys and girls. The first dose is given at ages 12-13 whilst the second is given 6-12 months later.

Currently, Gardasil is used, a vaccine that protects against four subtypes of HPV: 6, 11, 16, 18. As described above, HPV 16 and 18 are responsible for around 70% of cervical cancer cases, whilst HPV 6 and 11 are implicated in the development of genital warts.

Screening

The NHS Cervical Screening Programme (NHSCSP) is key to reducing the rate of invasive cancers. For more information see our note.

Safe sex

Practical information should be given on safe sex. Using barrier methods of contraception (i.e. condoms - though these do not eliminate risk) results in reduced exposure to HPV, as does having fewer partners.

It is important to understand that many patients will want an active sex life. Provide information and support for adults and young people to make decisions that are best for them.

Prognosis

Prognosis is dependent on stage at diagnosis, 96% diagnosed at the earliest stage survive a year or more.

The overall survival figures for patients with cervical cancer (in England) at one year are:

- 81.1% of women survive one year or more after diagnosis

- 61.4% of women survive five years or more after diagnosis

Those who are younger at diagnosis have improved survival. About 90% of women aged 15-39 survive five years whilst just 25% over the age of 80 will.

Based on figures from Cancer Research UK.

Last updated: April 2021

Further reading

- Jo's cervical cancer trust

- Cancer research UK

- NICE guideline [NG12]. Suspected cancer: recognition and referral.

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback