Ectopic pregnancy

Notes

Introduction

Ectopic pregnancies refer to any pregnancy that develops outside the endometrial cavity.

They affect approximately 1 in 90 pregnancies in the UK, translating to around 11,000 cases a year.

The key to safe management and minimising maternal mortality is prompt recognition. When missed or late presenting, ectopic pregnancies can lead to serious and potentially fatal complications.

Two national guidelines are available covering the diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy:

- RCOG/AEPU Joint Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Ectopic Pregnancy, Nov 16.

- NICE Guideline 126: Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management, Apr 19.

Site

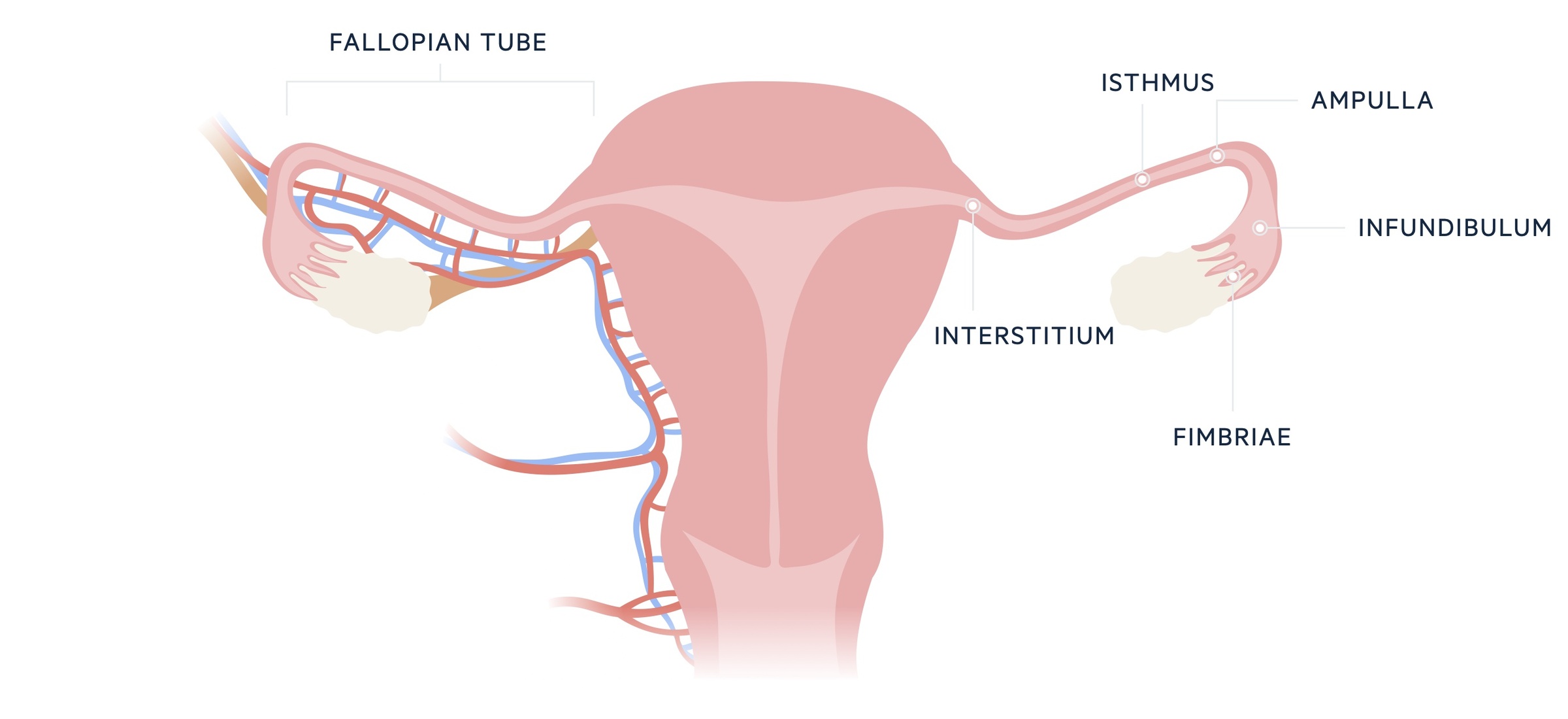

97% of ectopic pregnancies develop in the fallopian tube.

The fallopian tubes are by far the most common site of ectopic pregnancy. Any pathology (infection, adhesions, iatrogenic injury) that damages the tubes leads to an increased risk. The ampulla of the tube is the most common site followed by the isthmus, but they may implant anywhere along the length of the structure.

Ectopic pregnancies affecting the interstitium of the fallopian tube (termed interstitial pregnancies) are relatively rare, thought to account for around 2-6% of cases. They are harder to diagnose sonographically and are thought to present later due to the wider interstitial portion of the fallopian tube being able to accommodate larger pregnancies. Their location and larger size at presentation results in more catastrophic bleeding in the event of a rupture. This fact, combined with the diagnostic challenges, means the condition has a higher mortality than ectopics occurring elsewhere in the fallopian tube. In addition to transvaginal US, diagnosis may be aided by MRI or diagnostic laparoscopy.

The other 2-3% implant elsewhere, sites include the ovary, cervix, peritoneum and C-section scars.

Risk factors

A number of factors increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy, however, the majority of women have no identifiable risk factor.

- Previous ectopic pregnancy (risk is around 18.5%)

- IVF

- Fallopian tube damage (may be secondary to infection, surgery)

- Adhesions

- Smoking

- Intrauterine contraceptive device (overall the risk of ectopic pregnancy, and any pregnancy, is reduced, however, in the event of failure the proportion of pregnancies that are ectopic is increased)

- Progestogen-only pill (overall the risk of ectopic pregnancy, and any pregnancy, is reduced, however, in the event of failure the proportion of pregnancies that are ectopic is increased)

Clinical features

Features may be subtle and non-specific, patients with child-bearing potential must be offered a pregnancy test when presenting to hospital with an acute complaint.

Patients may or may not be aware that they are pregnant. Symptoms of tubal ectopics typically develop 6-8 weeks after the last normal period. Presentations range from mild abdominal upset with or without vaginal bleeding to hypovolaemic shock secondary to a ruptured tubal ectopic with significant blood loss. The features described here are predominantly for tubal ectopics though there may be significant cross-over with ectopics in other sites.

Symptoms

- Abdominal/pelvic pain

- Vaginal bleeding

- Amenorrhoea

- Shoulder tip pain (a sign of rupture and intra-abdominal bleeding, indicative of blood irritating the diaphragm)

- Urinary discomfort

- GI upset

Signs

- Abdominal/pelvic tenderness

- Rebound tenderness, peritonism

- Abdominal distention

- Pallor

- Cervical motion tenderness (refers to pain on movement of the cervix during a bimanual examination, indicative of pelvic inflammation)

Ruptured ectopic pregnancy

A ruptured ectopic pregnancy is a gynaecological emergency. There can be significant intra-abdominal bleeding leading to collapse and haemodynamic instability. Vomiting, diarrhoea and shoulder tip pain may be present. Vaginal bleeding may be present but often misleads regarding the degree of blood loss as much will be intra-abdominal.

Investigations

Trans-vaginal USS is the investigation of choice in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy.

Bedside

- Observations

- Urinary pregnancy test

- Urine dipstick

Bloods

- FBC

- U&Es

- CRP

- LFTs

- Clotting screen

- Group and saves

- Serum B-hCG (see chapter below for detail)

Imaging

Trans-vaginal USS: the standard investigation. It provides good visualisation and identifies the majority of tubal ectopic pregnancies during the first assessment. A minority of cases won’t be identified and are termed ‘pregnancy of unknown location (PUL)’. This may be due to the location or how early in the process someone is scanned.

Trans-abdominal USS: should generally only be used where the patient declines the transvaginal approach. You must explain the reduced sensitivity and specificity of this approach.

MRI: may be used as a second-line investigation and can be of particular use in cervical scar or interstitial ectopic pregnancies.

Serum B-HCG

Serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (B-hCG) is used to help guide the management of ectopic pregnancy.

B-hCG is a hormone produced by syncytiotrophoblastic cells of the placenta. It should be measured in any patient with a diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy where it can be used to help guide management (see the chapter below).

It is also used in pregnancy of unknown location (PUL). PUL refers to cases where there is an elevated B-hCG (indicating pregnancy) but no sonographic evidence of an intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy. The possibilities include early intrauterine pregnancy, unidentified (likely early) ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage. Care must be taken when interpreting serum B-HCG. A single serum B-HCG cannot be used to predict an ectopic pregnancy and a single low serum B-HCG does not exclude ectopic pregnancy. Refer to the RCOG/AEPU Joint Guidelines for more detail.

Management

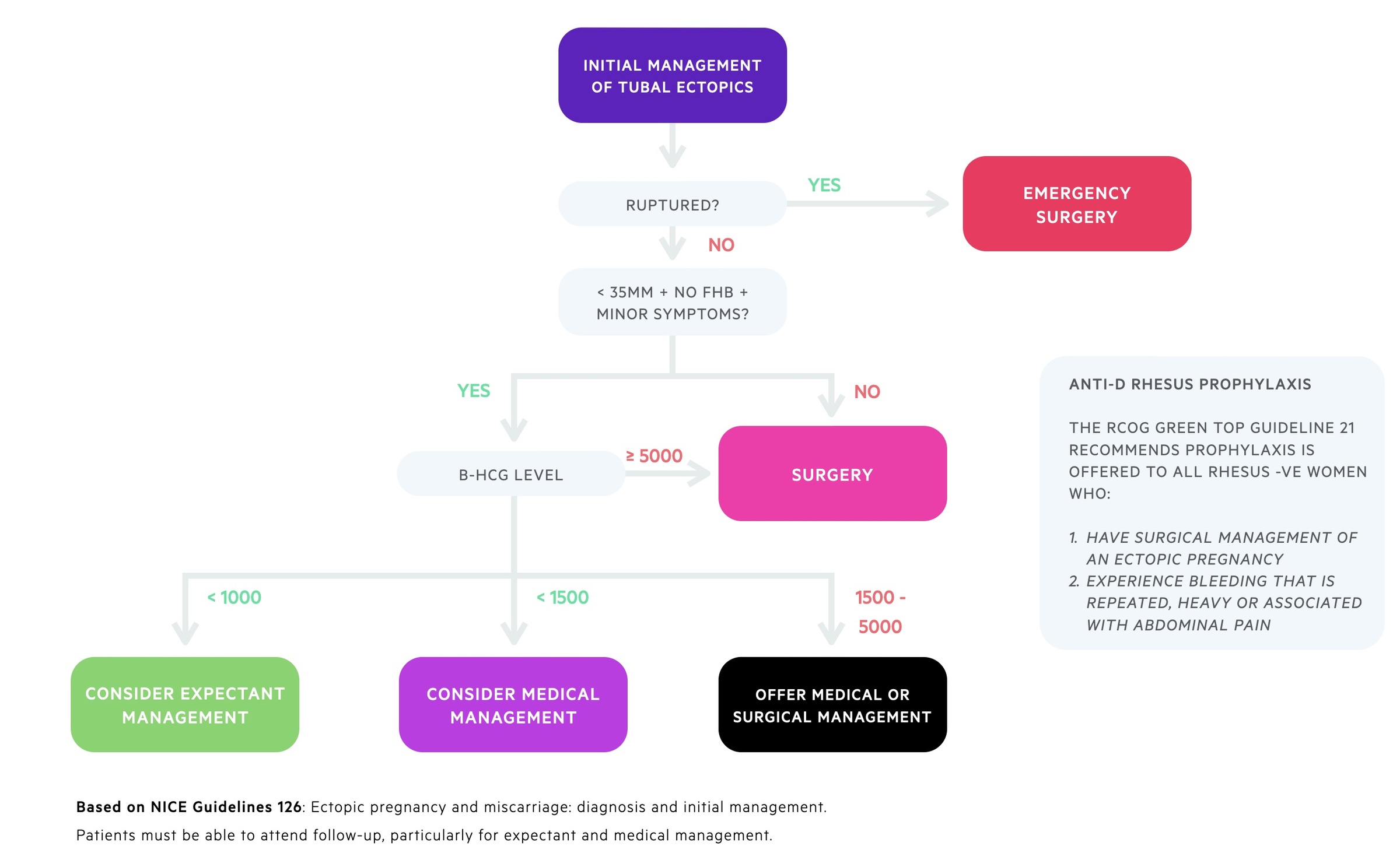

Management of ectopic pregnancy falls into three main types; expectant, pharmacological and surgical.

Here we discuss the management of tubal ectopics (excluding interstitial pregnancies). Though other locations may follow similar management schemes, the nuances are beyond the scope of this note.

Expectant management

This may be considered in carefully selected patients. They should be well, with only minor pain and low or declining B-hCG. Patients must also be willing and able to attend follow-up.

NICE guidelines 126 advise the following women are offered expectant management:

- Clinically stable and pain-free and

- Unruptured tubal ectopic pregnancy measuring less than 35 mm with no visible heartbeat on transvaginal ultrasound scan and

- Serum B-hCG levels of 1,000 IU/L or less and

- Able to return for follow-up

They also state it may be considered in women with serum B-hCG levels above 1,000 IU/L and below 1,500 IU/L.

Serum B-hCG should be measured at days 2, 4 and 7 and then weekly. Levels should fall by 15% at each measurement, if they do not arrange senior review.

Pharmacological management

Single-dose methotrexate (though some may require subsequent doses) can be considered as an alternative to surgery.

NICE guidelines 126 advise the following women are offered methotrexate:

- Have no significant pain and

- Have an unruptured tubal ectopic pregnancy with an adnexal mass smaller than 35 mm with no visible heartbeat and

- Have a serum B-hCG level less than 1,500 IU/litre and

- Do not have an intrauterine pregnancy (as confirmed on an ultrasound scan) and

- Able to return for follow-up

A choice of either methotrexate or surgical management should be offered to women with a B-hCG level 1,500-5,000 IU/litre, who are able to return for follow-up and meet all of these criteria:

- No significant pain

- Unruptured ectopic pregnancy with an adnexal mass smaller than 35 mm with no visible heartbeat

- No intrauterine pregnancy (as confirmed on an ultrasound scan)

Those managed with methotrexate should have serum B-hCG measured at days 4 and 7 and then weekly. If levels plateau or rise arrange senior review.

Surgical management

There are a number of indications for surgery, when indicated the laparoscopic approach should be used over open surgery when possible. There are two main terms to be aware of in the surgical management of tubal ectopics:

- Laparoscopic salpingectomy: laparoscopy refers to 'key-hole' surgery. Salpingectomy refers to the removal of a fallopian tube, in this case, the tube affected by the ectopic pregnancy. This is generally the preferred treatment.

- Laparoscopic salpingotomy: this refers to a procedure that aims to preserve the fallopian tube. The tube is opened and the ectopic is removed. It is generally considered if the contralateral tube is damaged or there are other fertility-based concerns.

Emergency surgery is indicated in patients with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. If the patient is unstable, assess in an ABCDE manner, escalate with peri-arrest and/or major haemorrhage call.

NICE guidelines 126 advise the following women are offered surgery as first-line management:

- Unable to return to follow up or

- An ectopic pregnancy and significant pain or

- An ectopic pregnancy with an adnexal mass of 35 mm or larger or

- An ectopic pregnancy with a foetal heartbeat visible on an ultrasound scan or

- An ectopic pregnancy and a serum hCG level of 5,000 IU/litre or more

Patients who have required salpingotomy require weekly serum B-HCG measurements until negative. Approximately 1 in 5 will need further treatment (e.g. methotrexate, salpingectomy).

Women who have had a salpingectomy should conduct a urinary pregnancy test at three weeks and contact the gynaecology department if positive.

Anti-D rhesus prophylaxis

Rhesus D (RhD) negative women may require anti-D rhesus prophylaxis.

Rhesus (Rh) refers to a group of red cell antigens, the most important being RhD. Problems arise when RhD-negative mothers have RhD-positive foetuses. Feto-maternal haemorrhage (FMH) can expose the mother to RhD-positive blood. In response, a RhD-negative mother generates anti(D) antibodies. In subsequent pregnancies anti(D) antibodies can cross the placenta and lead to haemolytic disease of the newborn.

Anti-D immunoglobulin is given to reduce the risk of maternal sensitisation in events where FMH is likely. The advice from NICE and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) is as follows (each trust will have local guidelines):

- NICE guidance 126 states anti-D rhesus prophylaxis should be offered to all RhD-negative women who have surgery to manage an ectopic pregnancy.

- RCOG/AEPU Joint Guideline advises anti-D rhesus prophylaxis should be offered to all RhD-negative women who have surgery to manage an ectopic pregnancy or where bleeding is repeated, heavy or associated with abdominal pain.

Support and counselling

An ectopic pregnancy can be one of the most traumatic experiences of a person's life.

They have to cope with losing a pregnancy during a potentially life-threatening condition. There are also potential issues with future fertility to contend with. A huge range of emotions may be experienced and will differ from patient to patient. It will also affect partners and close family and can put a strain on relationships.

Counselling is an individual decision though many will find it helps following an ectopic pregnancy. In addition, a number of charities offer support and guidance for both patients and clinicians:

Last updated: April 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback