Endometrial cancer

Notes

Overview

Endometrial cancer refers to malignancy of the lining of the uterus (i.e the endometrium).

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynaecological malignancy in developed countries. It is due to abnormal proliferation of endometrial cells, which commonly presents with abnormal uterine bleeding. Due to the early presentation with bleeding, the five-year survival is more favourable than some cancers, estimated around 75%.

EC is strongly linked to obesity. The rising rates of obesity has led to a significant increase in the incidence of EC. It is the sixth most common female malignancy worldwide.

The mean age of diagnosis is around 60 years for non-inherited EC. However, in 2-5% of cases, EC is linked to a familial cancer syndrome called Lynch syndrome. This is due to an inherited mutation in one of the mismatch repair genes. It can lead to early onset endometrial and colorectal cancer.

Types

EC is broadly divided into two main types: endometrioid and non-endometrioid.

The two types of EC are categorised according to histology (i.e. the cellular characteristics of the tumour). They differ by incidence, tumour behaviour and responsiveness to treatment.

- Endometrioid (Type I): 75-80% of EC. Earlier presentation and better prognosis. Stimulated by oestrogen. Typically follows period of endometrial hyperplasia.

- Non-endometrioid (Type II): 10-20% of EC. Multiple subtypes of tumour (e.g. serous, clear cell, mucinous). Serous and clear cell not associated with obesity and not stimulated by oestrogen.

Aetiology

EC is most commonly seen in post-menopausal women due to prolonged exposure to oestrogen.

The is no one cause of EC. Instead, it is the combination of multiple factors that increase the risk of developing cancer. In type I EC, the major risk factor for developing cancer is an excess of oestrogen. This can be endogenous due to obesity or exogenous due to the administration of oestrogen unopposed by progestins (e.g. hormone replacement therapy).

Obesity

Obesity is associated with an excess of adipose tissue. Adipose tissue, or fat, is not inert and secretes a number of peptide and steroid hormones. Adipose tissue increases the level of oestrogen because of the enzyme aromatase that is able to convert androgens to oestrogen. This increase in oestrogen is a major factor in the pathogenies of EC.

Other risk factors

- Unopposed oestrogen therapy

- Increasing age

- Tamoxifen therapy

- Early menarche & late menopause: increased time expose to oestrogen

- Nulliparity: never borne a child

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome: chronic anovulation

- Genetic risk (e.g. Lynch syndrome)

Pathophysiology

EC is characterised by the development of mutations, which promote uncontrolled cellular proliferation.

The development of any cancer is based on the acquirement of sequential mutations that allow a cell to proliferate uncontrollably. In EC, the prolonged exposure to oestrogen, which promotes endometrial proliferation, is central to the malignant process.

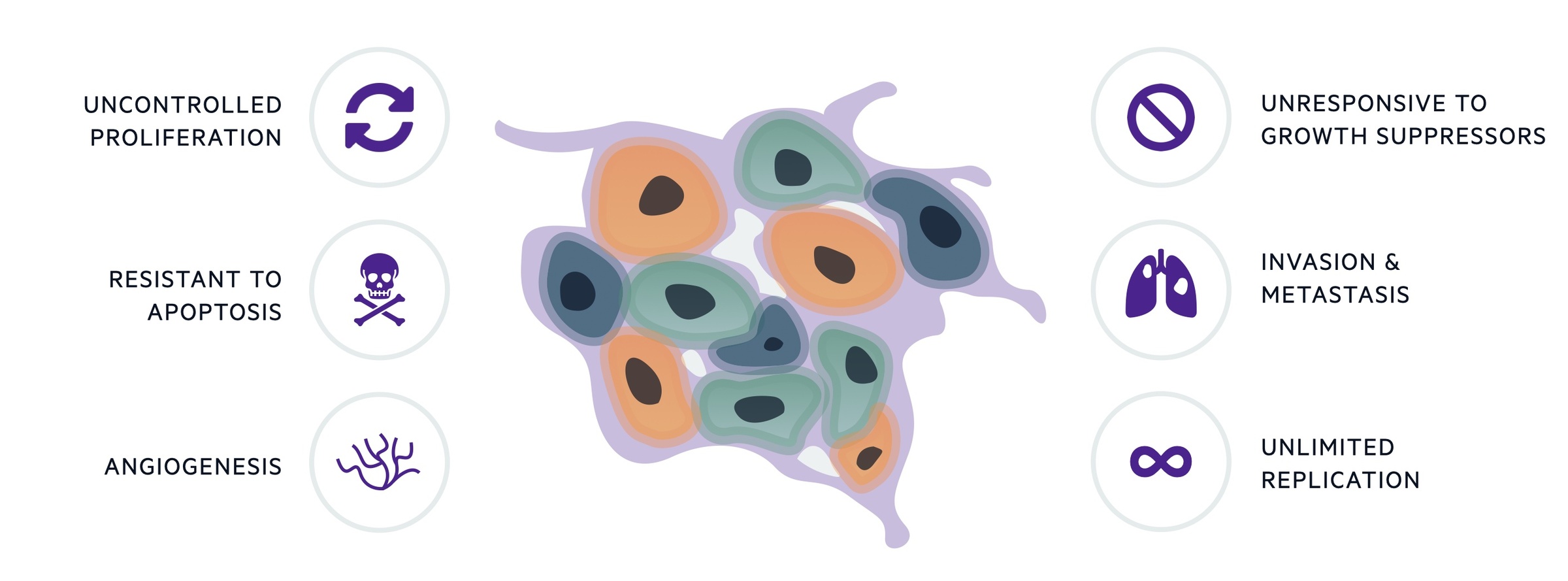

By itself, uncontrolled proliferation is not sufficient for cancer development. Malignant cells must develop mechanisms to support their growth, resist cell death and invade normal tissue. The ‘hallmarks’ of cancer help to conceptualise the acquired biological processes needed to promote transformation of normal cells into malignant ones, which is true of any cancer. The original six hallmarks have since developed into ten characteristics.

Lynch syndrome (LS)

LS is an inherited cancer syndrome, which is due to a germline mutation in one of the DNA mismatch repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2). When genetic mutations occur in germ cells, these can be passed onto our offspring and will be present in every cell within the body. The hallmark of LS is abnormal DNA repair, which leads to DNA replication errors that we call microsatellite instability (MSI). It can lead to early onset EC and colorectal cancer.

Up to one third of 'type I' ECs are associated with DNA replication errors causing MSI that we see in LS. However, in these non-inherited cancers, there is inactivation of the DNA mismatch repair genes in the tumour cells due to somatic mutations. Somatic cells refer to any cell in the human body other than reproductive (germ). Therefore, the mutations are local to the endometrial cells and cannot be passed to our offspring.

Clinical features

The classical presentation of endometrial cancer is post-menopausal bleeding.

EC is most common in older patients who have already gone through the menopause. This means post-menopausal bleeding (PMB) is a common presentation.

PMB is defined as abnormal vaginal bleeding ≥12 months after the last menstrual period in patients not on hormone replacement therapy (HRT). EC is detected in 5-10% of patients with PMB. It can be more difficult to diagnosis patients peri-/premenopausal.

Symptoms

- Postmenopausal bleeding

- Abnormal uterine bleeding: intermenstrual, frequent, heavy or prolonged

- Constitutional symptoms: weight loss, anorexia, lethargy

Signs

- Physical examination: typically normal (fixed, hard uterus suggests advanced disease)

- Cervical evaluation: may see abnormal tissue on speculum examination

Referral

NICE recommend a suspected cancer referral (two week wait) for patients with PMB.

Any patient with suspected cancer should be referred to the relevant specialty under the ‘two week wait’ rule. This means you should be referred and assessed within a two week period.

As cancers can present differently, there are numerous urgent referral pathways that exist. For suspected EC, nice recommend the following under the two-week wait urgent referral system:

- Referral: age > 55 years and PMB

- Consider referral: age < 55 years and PMB

In addition, you should consider referral for ultrasound to exclude EC in patients > 55 years with unexplained vaginal discharge who are presenting for the first time, or report haematuria or have high platelets. Alternatively, in patients >55 years with visible haematuria and low haemoglobin or high platelets or hyperglycaemia.

Diagnosis & investigations

Patients with suspected EC require an abdominal, pelvic and speculum examination alongside a transvaginal ultrasound.

Ultrasound

Currently, a transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the initial investigation of choice to assess the endometrial thickness in patients presenting with PMB. In the absence of any endometrial irregularity, a thickness level at 4mm is the cut-off for further investigation.

- < 4mm endometrial thickness: no further investigation required unless recurrent PMB

- ≥ 4 mm endometrial thickness: offer endometrial sampling, ideally as outpatient

In premenopausal women, there is no standard threshold for endometrial thickness on TVUS and additional factors needs to be considered to decide who should undergo endometrial sampling.

Endometrial sampling

Patients with suspected EC require a tissue sample to be taken to confirm the diagnosis. There are a number of methods that can be used. Ideally, this should be completed as an outpatient with a pipelle biopsy.

- Pipelle biopsy: completed in outpatient setting. Small straw-like tube (pipelle) is passed through the cervix to take an endometrial sample.

- Hysteroscopy and biopsy: hysteroscope passed into uterus for direct visualisation. Reserved for high-risk patients or those with focal area of irregularity. Required in patients unable to tolerate outpatient pipelle biopsy (e.g. cervical stenosis, discomfort). Regional or general anaesthesia.

Other investigations

Additional tests include blood tests, imaging and pre-operative risk assessment (if surgery is required). CT imaging can be used to look for distant metastasis (cancer spread) and an MRI of the pelvis may help better characterise local disease. These are essential in patients with high-risk features or high suspicion of advanced disease.

Staging & grading

The grade and stage provide important information about the behaviour and extent of any malignancy.

Endometrial samples should be sent to histopathology for further assessment to confirm the presence of EC and the particular type (i.e. endometrioid or non-endometrioid).

Once confirmed, it is important to determine both the grade and stage of the tumour. This tells us important information about the behaviour of the tumour, how advanced it is and what treatments are suitable. In EC, the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology (FIGO) is used to grade and stage the tumour.

Grading

The grade of a cancer describes how much resemblance the cancer cell has to the original cell type. Uterine cancer is divided into three grades (well, moderately and poorly differentiated).

A cell that does not resemble the original cell type is said to be ‘poorly differentiated’ and associated with more aggressive behaviour and worse outcome. A cell that does resemble the original cell type is said to be ‘well differentiated’ and generally associated with a better outcome.

Staging

The stage of a cancer is critical to determine treatments, but can be very complex and important mainly for clinicians involved in treating patients with cancer. Stage also provides prognostic information.

The stage of a cancer describes the extent of cancer spread based on tumour size, presence of lymph node involvement and distant spread. We call these three factors ‘TNM’ (tumour, nodes, metastasis).

- Tumour (T): size of tumour (usually in cm)

- Nodes (N): number and location of lymph nodes involved

- Metastasis (M): presence or absence of spread to a distant site

Management

Management of EC is based on the cancer type, grade and stage, patients co-morbidities and desire for fertility.

The options for treatment of EC include surgery, chemotherapy (cytotoxic therapies), radiotherapy (ionising radiation), brachytherapy (locally delivered radiotherapy) and hormonal treatments. All patients should be discussed in a specialist cancer multidisciplinary team meeting and given information about all their treatment options.

A brief summary of treatment options:

- Surgical treatment: total hysterectomy (removal of uterus) +/- bilateral salpingoopherectomy (removal or ovaries and fallopian tubes). Generally first-line option in early stage disease. Different surgical methods. May be combined with lymph node dissection.

- Chemoradiotherapy: may be combined with surgery. Can be given before surgery to shrink tumour. Options dependent on the stage, grade and risk of recurrence. Post-operative chemotherapy can be considered in specific cases.

- Unfit for surgery: options can include vaginal hysterectomy (regional anaesthesia), pelvic radiotherapy or hormonal therapy with progestogens or aromatase inhibitors.

- Fertility-sparing: <5% of EC occur in women under 45 years. Requires specialist gynae-oncology input with consideration of risk/benefits. Progestogens in selected patients, requires individualised care and regular follow-up.

- Other: new immunotherapies and biological therapies. Oncology rapidly growing field, new drugs continue to emerge

Prognosis

The overall five-year survival in endometrial cancer is approximately 75%.

Prognosis in cancer is largely determined by the stage of disease. Those with early stage cancer (i.e. local disease only) is associated with the best prognosis and those with advanced disease (i.e. spread widely) is associated with the worst prognosis. In EC the five-year survival for stage 1 is 90% compared to 15% for stage 4.

Last updated: June 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback