Ovarian cancer

Notes

Overview

Ovarian cancer refers to a malignancy arising from ovarian tissue.

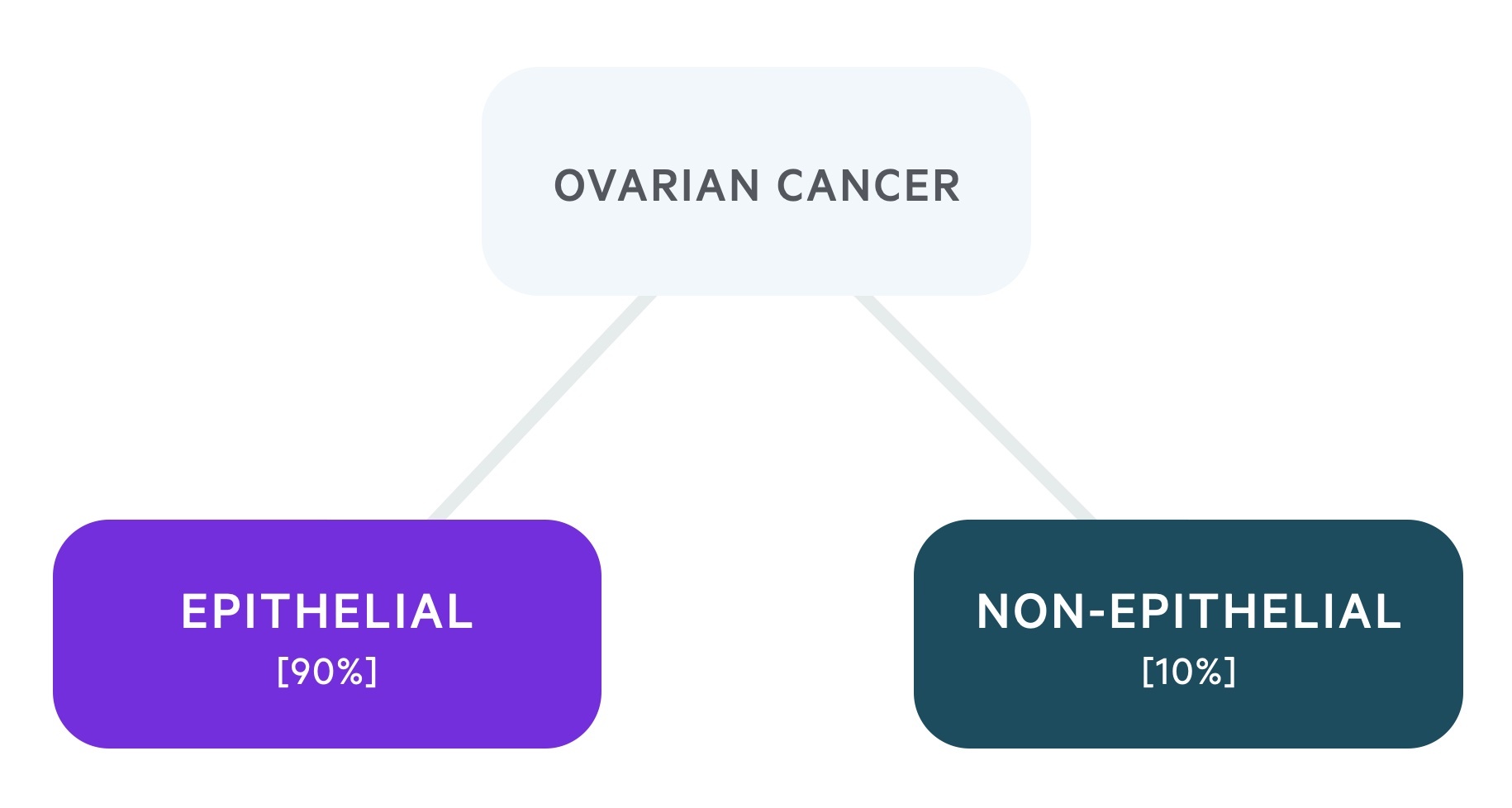

Ovarian cancer is the second most common gynaecological cancer following endometrial cancer. It is relatively rare before the age of thirty with incidence increasing with age (highest in those aged 75-79). The majority of ovarian cancers (around 90-95%) arise from epithelial cells, so-called epithelial ovarian carcinomas, with the remaining being classified as non-epithelial ovarian carcinomas.

It can be asymptomatic, particularly in early disease, and when features do develop they may be non-specific. As such it is often diagnosed at an advanced stage (60% diagnosed at stage III/IV). Treatment depends on the stage, underlying subtype and patient status but often involves surgical resection and chemotherapy.

Epidemiology

There are approximately 7,500 cases of ovarian cancer in the UK each year.

It is the sixth most common cancer in women. Incidence is highest in women aged 75-79. It is responsible for around 4,200 deaths a year.

In the UK, ovarian cancer is more common in White women when compared to those of Asian or Black ethnicity.

Figures from Cancer Research UK.

Classification

Ovarian cancers can be classified as epithelial or non-epithelial in origin.

Epithelial ovarian carcinomas

Epithelial ovarian carcinomas account for about 90% of ovarian cancers. The majority are thought to arise from the ovarian surface epithelium or the distal fallopian tube.

There are a number of subtypes:

- Serous: most common subtype, accounts for 60-70% of cases. May be divided into high grade and low grade. Thought to originate from the fallopian tube epithelium.

- Endometrioid: the second most common subtype, generally diagnosed at an early stage, a proportion are related to endometriosis. Some patients have concomitant endometrial cancer.

- Clear cell: around 10% of cases, often associated with endometriosis. Complications include paraneoplastic hypercalcaemia and thrombosis (e.g. DVT).

- Mucinous: rare, primary ovarian cancer has to be differentiated from other primary sources.

- Transitional cell (Brenner tumours)

- Undifferentiated

Non-epithelial ovarian carcinomas

Non-epithelial ovarian carcinomas account for around 10% of ovarian cancers. In those of Black and Asian heritage, where epithelial carcinomas are rarer, germ cell tumours account for a significant proportion of ovarian cancers.

There are many types including:

- Germ cell tumours: most common non-epithelial ovarian cancer, and is a common cause of ovarian cancer in patients younger than 35. Types include dysgerminoma, yolk sac tumours, immature teratomas and mixed tumours. They may be complicated by ovarian torsion or rupture.

- Sex cord and stromal tumours

- Carcinosarcoma

- Small cell cancer

Risk factors

Risk of ovarian cancer increases with number of ovulatory cycles and age.

- Age

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Endometriosis (this link is disputed, and the estimated increase in absolute risk is small)

- Asbestos

Hormonal

It is thought that the risk of ovarian cancer is proportional to the number of ovulatory cycles a woman has in a lifetime. As such the following are risk factors:

- Nulliparity (never having given birth)

- Early menarche (menarche refers to the first occurrence of menstruation)

- Late menopause

Ovarian cancer is less common in multiparous women, evidence also indicates that risk is reduced by breastfeeding. The prolonged use of the combined oral contraceptive has also been shown to reduce the risk of developing ovarian cancer.

Other hormonal risk factors include:

- In vitro fertilisation: appears to be a small increased risk following IVF.

- Hormone replacement therapy: there may be a small increased risk of ovarian cancer with prolonged use of HRT.

Genetic

- Positive family history

- BRCA 1/ BRCA 2

- Lynch syndrome

Clinical features

Ovarian cancer is often asymptomatic in the early stages and presents with non-specific features, as such it is frequently diagnosed late.

Clinical features may be absent for a significant period. When they develop, they are generally non-specific and can be ignored or incorrectly thought to be secondary to more benign conditions like irritable bowel syndrome.

Clinicians need to be acutely aware of ovarian cancer and its often vague presentation. A low threshold should be had to investigate patients presenting with suggestive, albeit often non-specific, features.

- Abdominal distension

- Early satiety (feeling full earlier than normal)

- Anorexia

- Change in bowel habit

- Abnormal or postmenopausal bleeding

- Pelvic or abdominal pain

- Urinary urgency

- Urinary frequency

- Weight loss

- Ascites

- Pelvic mass

Patients can also present with features of complications, typically relatively late in the natural history of the disease. It is not uncommon to see a patient on the General Surgical take with bowel obstruction secondary to previously undiagnosed ovarian cancer and adhesions. Other patients may present with breathlessness secondary to a malignant pleural effusion.

An acute presentation may also be prompted by ovarian torsion - for which ovarian cysts/masses are a risk factor. Ovarian torsion refers to a twisting of the ovary on its ligamentous support resulting in partial or complete obstruction of blood supply to the ovary. Patients typically present with severe pelvic pain often accompanied by vomiting and shoulder tip pain.

It may also present with thrombotic complications (e.g. deep vein thrombosis) and occasionally a paraneoplastic syndrome (e.g. paraneoplastic hypercalcaemia or cerebellar degeneration).

Referral

NICE guidance outlines when to refer or order investigations in patients with suspected ovarian cancer.

NICE guideline 12: Suspected cancer: recognition and referral (2021 update) details several scenarios. An urgent referral to gynaecological cancer services is indicated where physical examination identifies:

- Ascites and/or

- A pelvic or abdominal mass (which is not obviously uterine fibroids)

Further investigations (ordered in primary care) should be offered to any woman (particularly over the age of 50) with any of the following symptoms that are persistent or frequent (particularly if > 12 times per month):

- Persistent abdominal distension (women often refer to this as 'bloating')

- Feeling full (early satiety) and/or loss of appetite

- Pelvic or abdominal pain

- Increased urinary urgency and/or frequency

Further investigations for ovarian cancer are also advised in any woman over the age of 50 with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in the past 12 months. Other triggers for investigations include unexplained weight loss, fatigue or changes in bowel habit (these may also trigger investigations for other pathologies).

CA125

CA125 is a glycoprotein and tumour marker used in the diagnosis of epithelial ovarian cancer.

The normal range is 0-35 IU/ml, though levels are known to vary with age and between ethnic groups. Its measurement forms a core component of the suspected ovarian cancer work-up and is used in the Risk of Malignancy Index (see below).

It is raised in around 80% of patients with ovarian cancer, however, this is closer to 50% in those with early disease (stage 1).

CA125 is a relatively non-specific tumour marker and may be raised in a number of malignancies including that of the pancreas, breast, lung, colon and endometrium

In addition, CA125 can be raised in a number of benign conditions including endometriosis, liver disease, pelvic inflammatory disease and during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Investigations

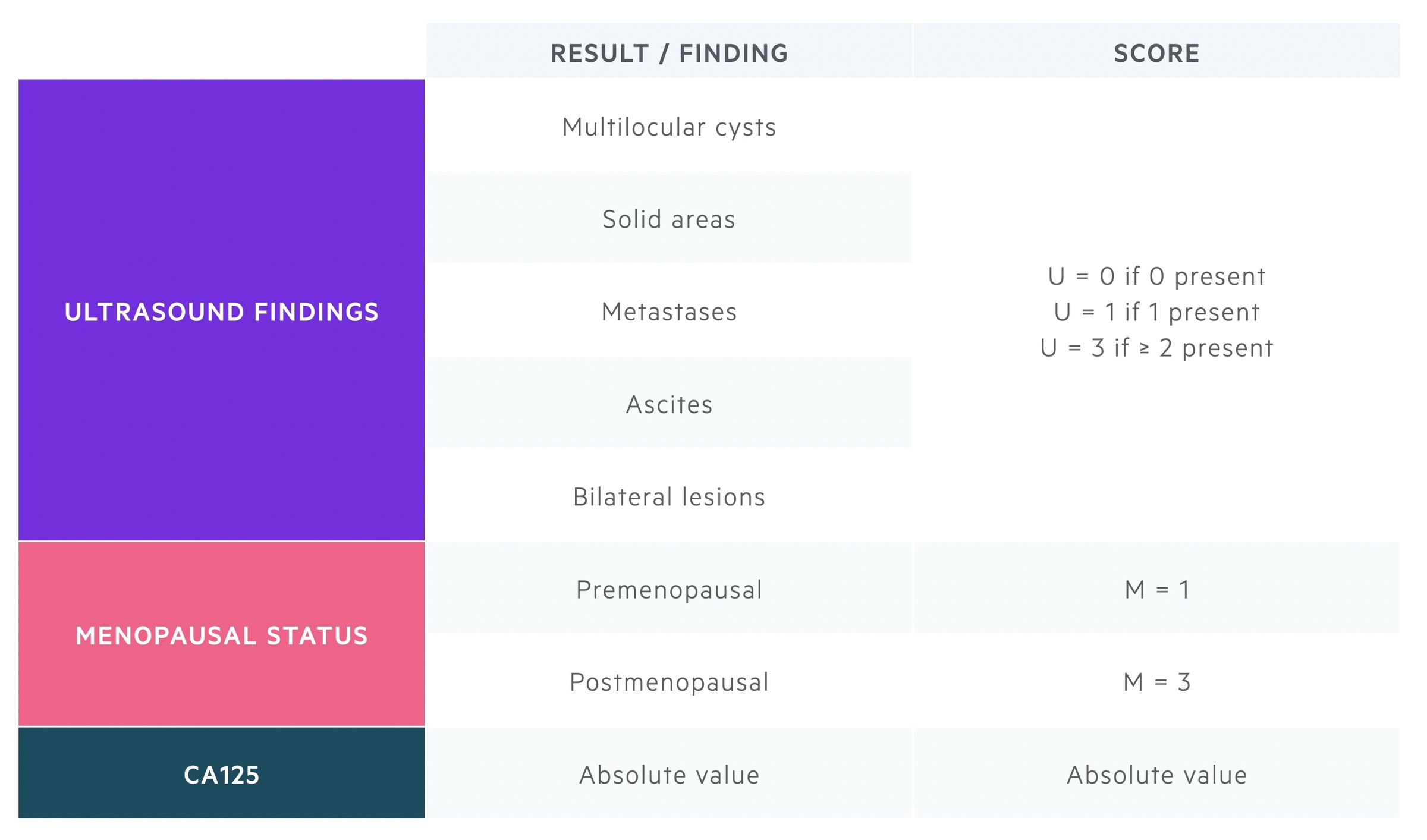

Diagnostic tests typically begin with USS and CA125, which along with menopausal status are used to calculate the Risk of Malignancy Index.

Diagnosis of ovarian cancer can be via a number of routes. Commonly investigations will follow a presentation to GP with persistent non-specific symptoms. Others may be diagnosed after an acute presentation to hospital or incidentally on imaging.

There are two national guidelines from SIGN (2013) and NICE (2011). The British Gynaecological Cancer Society (BGCS) also published guidance in 2017.

Initial investigations

A Ca125 +/- USS are typically the first investigations ordered in patients with suspected ovarian cancer. These can be used to calculate the Risk of Malignancy Index.

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) can be sent in women under the age of 40 to help identify non-epithelial ovarian cancers.

Risk of Malignancy Index (RMI)

The RMI score is calculated from the CA125, menopausal status and ultrasound findings. It is the product of the three scores (U = USS, M = Menopausal status):

RMI = U x M x CA125

A number of RMI scores exist - primarily with differences in how ultrasound findings are scored. NICE and SIGN guidelines advise the RMI 1 score is used.

Further investigations

Local services may have different RMI cut-offs regarding discussion at specialist MDT (NICE advise > 250, SIGN advise > 200), with other patients being managed at local centres. Additional investigations are likely to be ordered including CT scans (for radiological staging) and other tumour markers.

Depending on patient findings and MDT discussion many further tests may be ordered. This may include gastroscopy, colonoscopy, hysteroscopy, mammography and biopsies.

Tissue diagnosis

The final diagnosis is often obtained during surgery after appropriate MDT discussion. In cases where cytotoxic chemotherapy is being offered for advanced disease, a histological sample is normally attained before treatment is commenced.

Staging

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system (2014 revision) is commonly used to stage ovarian cancer.

Stage I

- IA: Tumor limited to 1 ovary, capsule intact, no tumor on surface, negative washings.

- IB: Tumor involves both ovaries otherwise like IA.

- IC:

- IC1: Surgical spill

- IC2: Capsule rupture before surgery or tumor on ovarian surface.

- IC3: Malignant cells in the ascites or peritoneal washings.

Stage II

- IIA: Extension and/or implant on uterus and/or Fallopian tubes

- IIB: Extension to other pelvic intraperitoneal tissues

Stage III

- IIIA:

- IIIA1: Positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes only, (i) Metastasis ≤ 10 mm (ii) Metastasis > 10 mm

- IIIA2: Microscopic, extrapelvic (above the brim) peritoneal involvement ± positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes

- IIIB: Macroscopic, extrapelvic, peritoneal metastasis ≤ 2 cm ± positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Includes extension to capsule of liver/spleen.

- IIIC: Macroscopic, extrapelvic, peritoneal metastasis >2 cm ± positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Includes extension to capsule of liver/spleen.

Stage IV

- IVA: Pleural effusion with positive cytology

- IVB: Hepatic and/or splenic parenchymalmetastasis, metastasis to extra-abdominal organs (including inguinal lymph nodes and lymph nodes outsideof the abdominal cavity)

Management

Management of ovarian cancer is primarily through surgery and chemotherapy.

Management of ovarian cancer is enormously complex and depends on a myriad of factors. It is decided on a case by case basis and guided by specialist MDTs. Here we will discuss the general management principles for epithelial ovarian cancer.

Surgery

Surgery (for patients who are fit) may be used to confirm diagnosis, stage disease and remove tumour bulk. Intra-operative frozen section can be used to help establish the likely diagnosis

The goal is normally to remove all visible tumour (macroscopic resection) and to complete surgical staging of the disease. Where complete macroscopic resection is not possible, as much tumour burden is removed (optimal cytoreduction).

In early disease (stage 1a, grade 1/2), there can at times be discussion regarding fertility-preserving surgery, but this has risks associated.

Chemotherapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy (i.e. given after surgery) is commonly used. This is often using Carboplatin monotherapy or Carboplatin & Paclitaxel. Chemotherapy can often be omitted in early disease, confined to the ovaries (stage IA, IB), with optimal surgical staging and a low histological grade (grade 1/2).

In advanced disease, surgery may follow neoadjuvant chemotherapy (i.e. given before a planned surgery) or be used as the primary management.

Prognosis

The prognosis of ovarian cancer is highly dependent on the stage at diagnosis.

When diagnosed at its earliest stage, 98% survive a year or more. However this falls to 54% when diagnosed at the latest stage - highlighting the significance of the issue of late diagnosis.

- Overall 71.7% survive one year or longer after diagnosis

- Overall 42.6% survive five years or longer after diagnosis

Patients who are younger at diagnosis have better survival. Around 90% of those aged 15-39 will survive five years or more.

Figures from Cancer Research UK.

Last updated: April 2021

Further reading

NICE CG 122: Ovarian cancer: recognition and initial management

SIGN 135: Management of epithelial ovarian cancer

Cancer Research UK: Ovarian cancer

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback