Antepartum haemorrhage

Notes

Introduction

Obstetric haemorrhage, which includes both antepartum and postpartum haemorrhage, is the leading cause of maternal death worldwide.

Within the UK, maternal death from obstetric haemorrhage is uncommon, but it still causes approximately 4-7 deaths per year. Obstetric haemorrhage is a common cause of both maternal and neonatal morbidity.

Antepartum haemorrhage (APH) complicates approximately 3-5% of all pregnancies. It is estimated that up to 20% of very preterm babies are born in association with an APH.

APH is defined as any vaginal bleeding from 24 weeks gestation until delivery. Bleeding that occurs within the first 24 weeks of gestation is known as bleeding in early pregnancy.

Aetiology

The main causes of APH are either local bleeding or problems with the placenta.

A full assessment looking for the potential causes of APH is essential in all cases, although some may remain unexplained.

APH from local bleeding may be the result of vaginal or cervical pathology or secondary to trauma. Problems with the placenta in APH can be divided into placental abruption, placenta praevia and vasa praevia.

Placental abruption

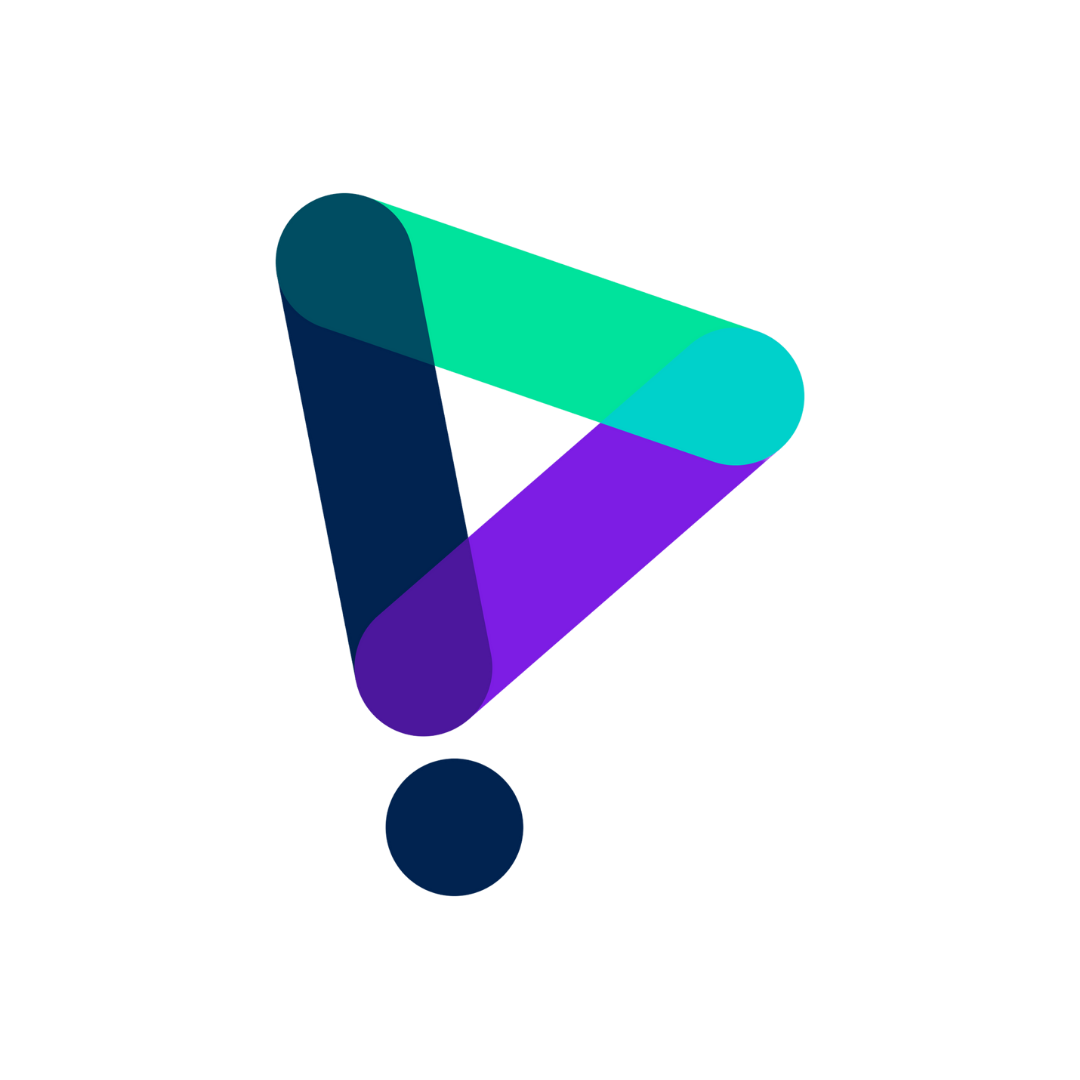

Placental abruption refers to either partial or complete separation of the placenta from uterus prior to delivery.

In placental abruption, bleeding may be obvious or concealed behind the placenta. Previous placental abruption is the most significant risk factor. Modifiable risk factors include cocaine, amphetamine and tobacco use, all should be discouraged to reduce rates of placental abruption (as well as other pregnancy complications).

The main risk factors for placental abruption are listed:

- Previous abruption

- Preeclampsia

- Intra-uterine growth restriction

- Non-vertex presentation

- Polyhydraminos (raised liquor volume)

- Older mother

- Multiparity

- Low BMI

- Assisted reproduction

- Intrauterine infection

- Abdominal trauma (consider domestic violence)

- Smoking

- Cocaine/amphetamine use

Placenta praevia

Placenta praevia refers to a placenta that is near or covering the internal cervical os within the lower segment of the uterus.

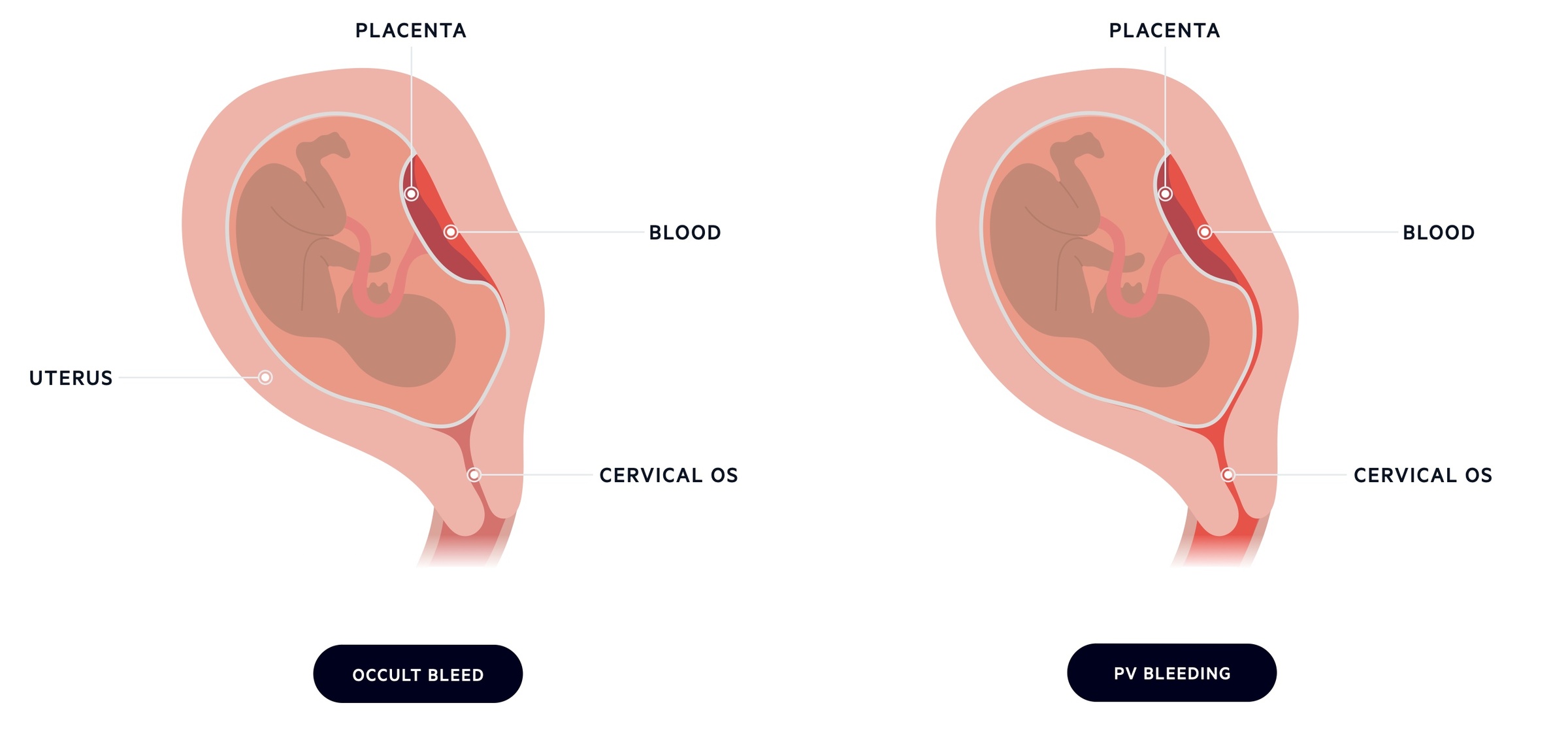

Traditionally, placenta praevia could be divided into major (complete) or minor (partial) depending on the distance from the internal cervical os.

- Major/Complete: placenta lies over the internal cervical os.

- Minor/Partial: leading placental edge is in the lower uterine segment but not covering the os.

This system determined placental location based on a vaginal examination. Ultrasound is now used to provide an accurate assessment of placental location.

Placentas are often low at the 20-week anomaly scan. Women with low placentas will be re-scanned at around 32 weeks gestation to confirm whether the placenta remains low. If the placenta covers the internal cervical os or the placental edge is within 2cm of the os, the foetus will need to be delivered by caesarean section.

If a low-lying placenta invades the myometrium it is termed an invasive placenta. The number of previous c-sections is the biggest risk factor.

Main risk factors for placenta praevia are listed:

- Previous C-Section

- Previous TOP

- Deficient endometrium (secondary to uterine scar, endometritis, curettage, etc)

- Multiparity

- Age > 40yrs

- Multiple pregnancy

- Smoking

- Assisted reproduction

Vasa praevia

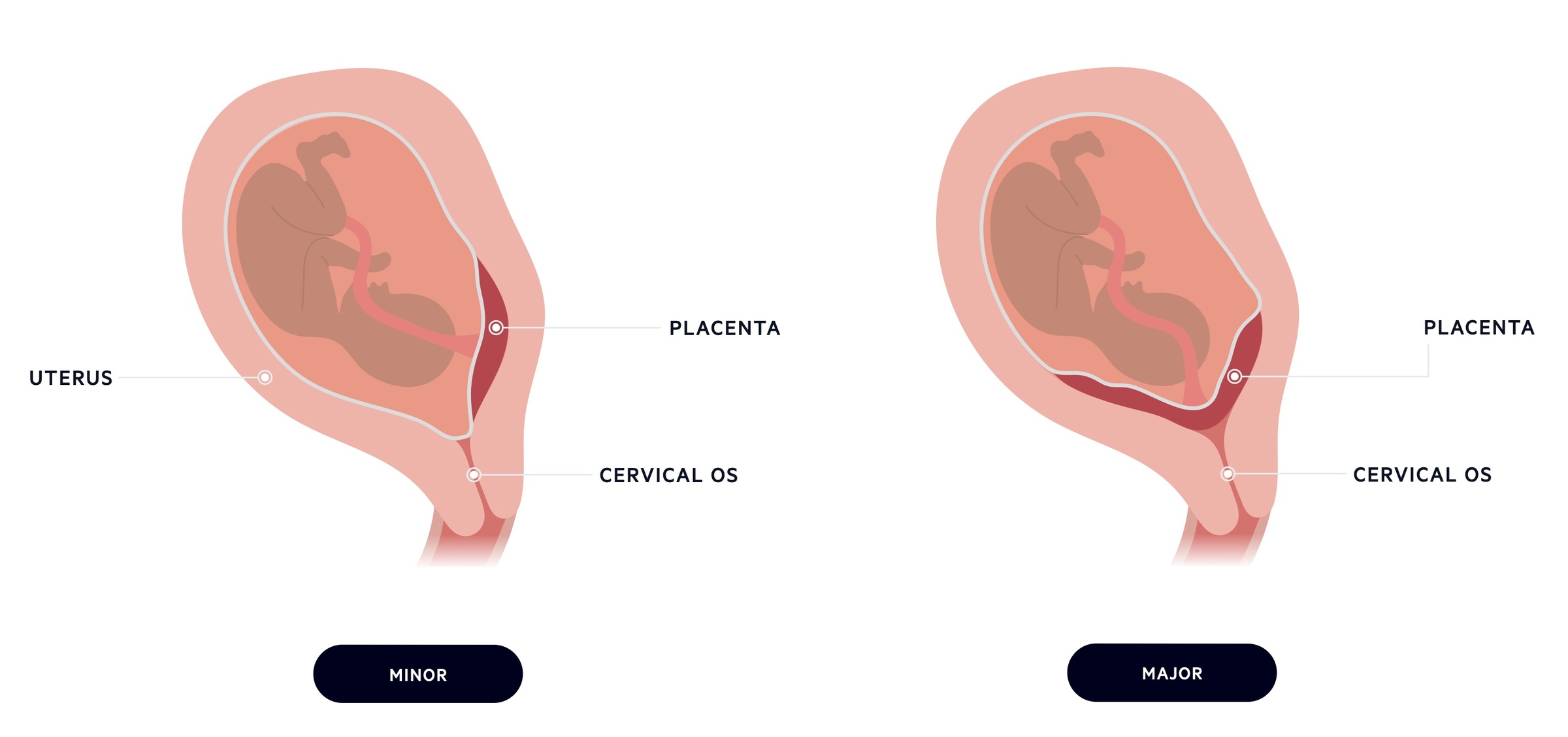

Vasa praevia is defined as the presence of fetal placental vessels lying over internal cervical os.

In vasa praevia, the fetal vessels course through the membranes over the internal cervical os and below the fetal presenting part. They are unprotected by placental tissue or the umbilical cord.

The typical history of an APH associated with vasa praevia is bleeding from spontaneous rupture of membranes (SROM). It is fetal, not maternal, blood that is lost in vasa praevia. Additionally, given the baby’s small blood volume, relatively small bleeds can be fatal.

There are two major types of vasa praevia:

- Type 1: due to a velamentous cord - where the cord inserts into the chorioamniotic membrane with vessels not protected by Wharton's jelly or the placenta and crossing the cervical os.

- Type 2: due to a bilobed or accessory placenta with connecting vessels that cross the cervical os.

Additional risk factors include multiple pregnancy, and IVF. When it is diagnosed antenatally, an elective caesarean section will be recommended at around 35-37 weeks gestation.

Severity

The extent of blood loss in APH is often underestimated and may be concealed.

The severity of APH is dependent on the extent of blood loss and clinical signs of shock.

- Minor APH: < 50 mls and stopped

- Major APH: 50-1000 mls, no sign of shock

- Massive APH: > 1000 mls or signs of shock.

Assessment

The assessment of any APH should involve a good history, examination and initiating early management.

History

Important questions to determine in the history include:

- When?

- What?

- Fresh red - new bleed

- Dark brown - old blood

- Mucous - think cervical plug

- Associated with waters breaking? (think vasa praevia)

- Quantity? (i.e. spotting, cupful, soaked clothing)

- Provoked by sexual intercourse?

- Abdominal Pain?

- Confirm placental position on last scan.

Examination

Important components of the examination include:

- Basic observations: are there features of shock?

- Abdominal palpation: does the uterus feel stony hard suggesting abruption?

- Speculum: is the source obvious in vagina, on cervix or coming through external os?

- Consider cervical assessment: is this early labour?

- Do not perform vaginal examination if known placenta praevia.

Initial management

The initial management of any APH should involve assessment with 'ABC' (airway, breathing, circulation), early establishment of intravenous access and the use of cardiotocography (CTG) to assess the baby.

- Intravenous access

- Urgent bloods for FBC, G&S, Crossmatch if major, U&Es, LFTs, Coagulation

- AntiD immunoglobulin should be offered to rhesus negative patients with potentially sensitising events, fetal maternal haemorrhage test can be used

- CTG: method of monitoring foetal heart rate and maternal contractions. Able to assess for foetal distress

Management

The management of an APH depends on the extent of bleeding, symptomatology of the mother and gestational age.

When the mother has mild spotting only and the baby is deemed okay, they can be considered for discharge. Mothers with bleeding heavier than spotting need to be admitted and monitored for a minimum of 24 hours following the bleed and until it stops.

If there is an unexplained minor APH, but settles, mothers can be discharged with a plan for serial growth ultrasound to assess for the following:

- Oligohydramnios

- Pre-term pre-labour rupture of membranes (PPROM)

- Intra-uterine growth restriction (IUGR)

- Premature delivery

- Need for C-Section

In the presence of an APH, steroids should be considered for fetal lung maturation if at 24-34+6/40. If the mother is > 37/40 with minor or major APH, and both mother and baby are well, then the recommendation is for induction of labour (IOL). Confirmation that there is no placenta praevia is essential prior to IOL.

Management sequence

The following steps are critical to the management of any APH.

- ABCDE approach

- Fluid resuscitation

- Blood products (as needed)

- Escalate to multidisciplinary seniors (obstetrics, anaesthetics, midwifery, neonatal).

- Mother and baby stable - discuss with a consultant, consider induction of labour

- Induction of labour is by artificial rupture of membranes & syntocinon

- The aim should be for a vaginal delivery if possible

- The same management is considered if the mother is stable with intrauterine death (IUD)

- Mother and baby unstable - discuss with consultant, emergency C-section

- Anticipate post-partum haemorrhage

Complications

The complications of an APH can be divided into either maternal or foetal/neonatal.

Maternal

- Need for emergency caesarean section

- Anaemia

- Need for blood transfusion

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Organ failure

- Death

Foetal/Neonatal

- Premature delivery

- Hypoxic injury

- Anaemia

- Intra-uterine death

- Neonatal death

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback