Hyperemesis gravidarum

Notes

Overview

Hyperemesis gravidarum refers to severe nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.

Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy affects around 80-90% of women. In its more severe form it is referred to as hyperemesis gravidarum. These terms can be defined as follows:

- Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: refers to nausea and vomiting with onset in the first trimester when other causes are excluded. Symptoms tend to develop between 4 - 7 weeks and resolve by 20 weeks in most women.

- Hyperemesis gravidarum: this is diagnosed in patients with protracted nausea and vomiting and the following triad:

- > 5% pre-pregnancy weight loss

- Dehydration

- Electrolyte imbalance

Epidemiology

Hyperemesis gravidarum is thought to affect between 0.3 - 3.6% of pregnancies.

Nausea and vomiting are very common and thought to affect up to 90% of pregnancies. Data for both conditions varies widely but it appears young women, those in their first pregnancy and multiple pregnancy are more commonly affected.

There appears to be a genetic component to hyperemesis gravidarum with women whose mothers were affected being far more likely to develop the condition themselves. Recurrence in future pregnancies is common though the reported figures vary wildly.

Pathogenesis

It is thought beta human chorionic gonadotropin (BhCG) contributes to the development of hyperemesis gravidarum.

Levels of BhCG are known to rise in the first trimester and it has been observed that women with higher levels are more likely to develop hyperemesis. The condition is also more common in multiple pregnancy and molar pregnancies where HCG levels are higher.

Abnormal gastric motility that is seen in pregnancy is also implicated. As discussed above in the ‘Epidemiology’ section there does appear to be a genetic component for hyperemesis gravidarum. Women with a significant family history are more likely to be affected.

Clinical features

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy tends to develop between 4 - 7 weeks gestation.

Symptoms tend to peak at around 9 weeks and 90% of cases resolve by 16 - 20 weeks. As defined above, hyperemesis is a severe form characterised by significant dehydration and electrolyte imbalances (e.g hypokalaemia).

Dehydration can be seen in reduced skin turgor and dry mucus membranes. Though normally asymptomatic, hypokalaemia can result in weakness, malaise and arrhythmias.

Differential diagnosis

Alternative causes of nausea and vomiting should be considered and excluded.

There are many conditions that feature nausea and vomiting - these must all be considered with the given context of each individual presentation. Red flag signs like abdominal pain and dysuria shouldn't be missed. Some of the differentials are listed below:

- Gastroenteritis

- Acute pancreatitis

- PUD

- Gastritis

- H.pylori infection

- Cholecystitis

- Urinary tract infections

- Metabolic conditions (e.g. DKA)

- Drug-induced nausea & vomiting

PUQE-24 scoring system

The Motherisk PUQE-24 scoring system can help to assess the severity of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.

The score is calculated based upon the response to three questions, evaluating symptoms over the past 24-hours. The addition of the three assigned scores gives an overall assessment of severity (mild ≤ 6, moderate = 7–12 and severe = 13–15).

Investigations

The investigations ordered depend on the severity of symptoms; checking electrolytes, monitoring blood sugar and assessing for starvation ketosis may all be indicated.

Bedside

- Vital signs

- Blood sugar

- Urine dipstick (in particular ketones)

- MSU

Bloods

- FBC

- Urea and electrolytes

In refractory cases or for patients with previous admissions:

- Liver function tests

- Amylase

- Thyroid profile

- Bone profile (for calcium & phosphate)

- Magnesium

- ABG/VBG

Ultrasound

An USS is used to confirm a viable intrauterine pregnancy. It can also identify multiple pregnancies or trophoblastic disease (e.g. molar pregnancy).

Management

Management involves supportive measures including antiemetics and appropriate fluid rehydration.

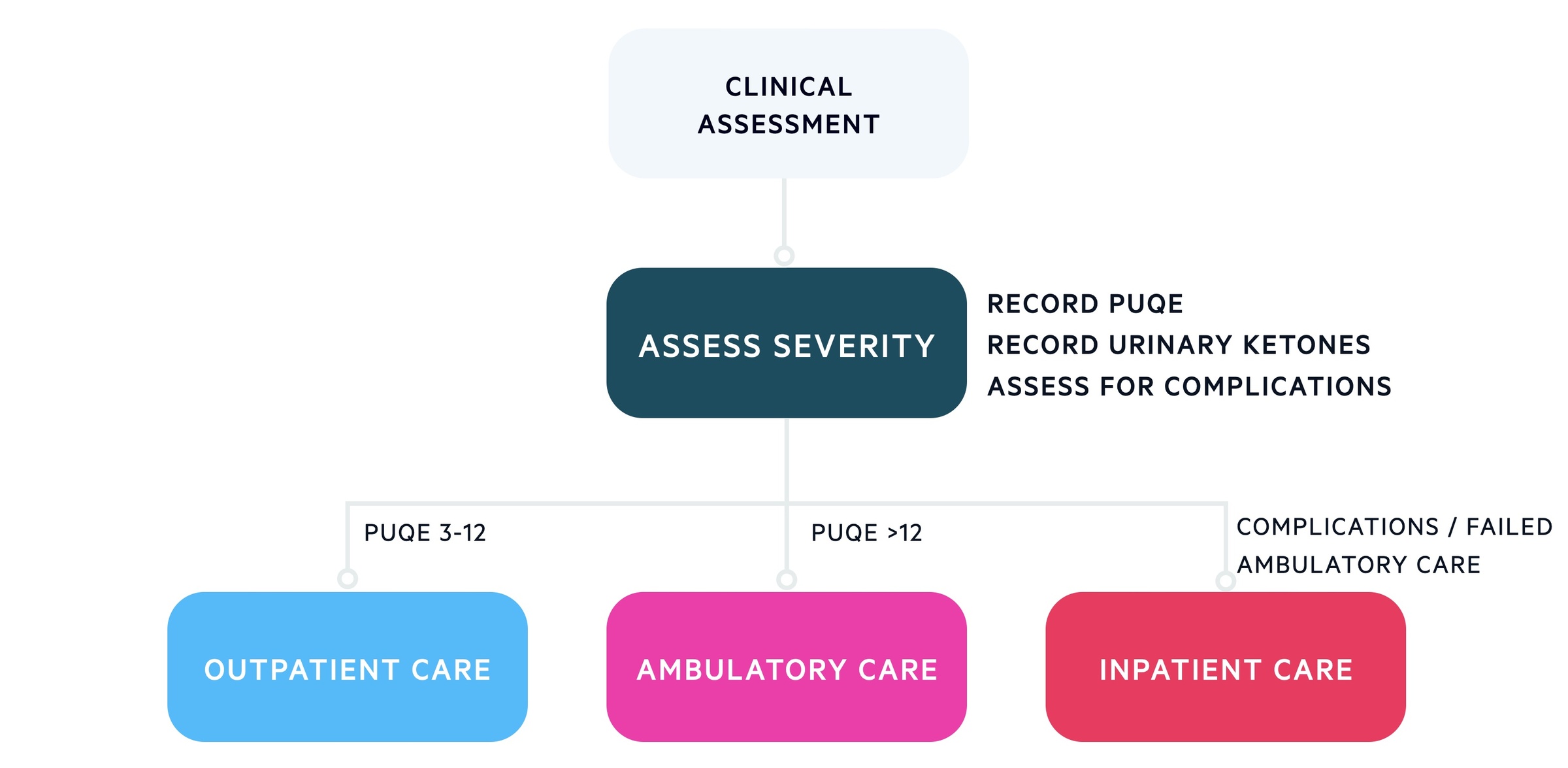

The management is dependent on the severity of symptoms and follows the guidelines set out by RCOG. The options include outpatient care, ambulatory care and inpatient management (see below). Antiemetics are central to the management of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy and hyperemesis:

- First-line options: cyclizine, prochlorperazine, promethazine, chlorpromazine

- Second-line options: metoclopramide, domperidone

- Third-line options: corticosteroids (initially hydrocortisone IV converted to prednisolone orally when able)

Fluid replacement and maintaining good hydration is important. In those managed as an inpatient or via ambulatory care, IV replacement can be given. The fluid of choice is normal saline with potassium supplementation as appropriate. Dextrose should not be given without first administering (and giving further doses of) Pabrinex to avoid precipitating a Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

In more severe cases ongoing monitoring of electrolytes with appropriate replacement is indicated.

Outpatient/community

Women with mild symptoms who are not dehydrated can generally be managed in the community with oral antiemetics. This accounts for the majority of cases of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.

They require support, information and a plan in case symptoms worsen. Oral hydration and dietary advice should be given.

Ambulatory care

Women who require more regular review and IV therapies can be managed through ambulatory care services. Daily review with IV antiemetics, fluids and Pabrinex (vitamin C and B vitamins) and repeat blood tests when necessary. Urine dips are used to monitor for resolution of ketonuria.

Inpatient management

This tends to be reserved for patients with hyperemesis / severe nausea and vomiting. This includes the following patients:

- Symptoms refractory to oral therapy/ambulatory care

- Ketonuria/weight loss > 5% despite oral therapies

- Have co-morbidity/complication requiring inpatient care

Again patients receive appropriate thromboprophylaxis and management with IV antiemetics, fluids and Pabrinex (vitamin C and B vitamins). Urine dips are used to monitor for resolution of ketonuria.

Last updated: June 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback