CRAO

Notes

Overview

Central retinal artery occlusion leads to sudden onset, painless, loss of vision.

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) was originally described in the 19th century in the context of infective endocarditis.

CRAO is due to occlusion of the central retinal artery, which causes ischaemia of the retina and sudden monocular visual loss. It is considered an ophthalmic emergency and essentially a type of stroke affecting the retinal artery.

Epidemiology

CRAO is rare, estimated to affect 1-10 per 100,000 people.

CRAO is more commonly seen in patients with traditional cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. diabetes, hypertension, smoking). It is more likely in older patients with a mean presentation between 60-65 years old.

Aetiology

Atherosclerotic disease is the most common cause of CRAO.

CRAO occurs due to occlusion of the retinal artery, usually due to an embolic event secondary to atherosclerotic disease. This is most commonly seen in older patients. In younger patients (i.e. < 40 years old) it is important to consider alternative causes (e.g. vasculitis, artery dissection).

Broad causes of CRAO:

- Cardiovascular

- Vascular diseases

- Inflammatory

- Haematological

- Rare

Cardiovascular

Atherosclerotic disease affecting the carotid arteries and embolic events arising from the heart are some of the most common causes of CRAO. These are typically seen in patients with traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

- Carotid artery atherosclerotic disease (~30%): embolic fragments may break off and occlude the retinal artery

- Cardioembolic events: embolic event arising from the heart. Usually secondary to atrial fibrillation and clot formation in the left atrial appendage

- Small vessel disease: local atherosclerotic disease

Vascular diseases

Any vascular disease affecting the carotid, ophthalmic or retinal arteries can potentially lead to CRAO.

- Carotid artery dissection: can lead to CRAO if extension into, and occlusion of, the retinal artery

- Fibromuscular dysplasia: narrowing of arterial lumen due to arterial wall abnormalities that are non-inflammatory, non-atherosclerotic.

- Fabry disease: rare x-linked inherited lysosomal storage disease. Possible cause of stroke in young patients.

Inflammatory

CRAO may be the presenting feature of giant cell arteritis (GCA). GCA is an inflammatory conditions that can present with sudden visual loss if it affects the ophthalmic or retinal arteries. Approximately, 2% of patients with CRAO have underlying GCA. Always suspect it with other typical features in older patients.

See our notes for more information on giant cell arteritis.

Rare

- Infections: cause a secondary vasculitis or retinal artery (e.g. toxoplasmosis)

- Complication of ophthalmic surgery

- Fat or amniotic fluid embolus

Pathophysiology

The central retinal artery supplies the surface of the optic nerve and inner retina.

Arterial anatomy

The first branch of the internal carotid artery is the ophthalmic artery, which supplies the eye. The retina is supplied by two main arterial systems that arise from the ophthalmic artery:

- Retinal arteries

- Ciliary arteries

The retinal artery divides into the superior and inferior branches, which further divides into nasal and temporal terminal branches. These arteries supplies the inner retina. The ciliary arterial system supplies the outer retina. However, in 15-30% of individuals, a small area of the inner retina including macula is supplied by the ciliary arterial system via the cilioretinal artery.

Clinical presentation

The severity of visual loss depends on the location of occlusion. Proximal ophthalmic occlusion would lead to significant visual loss. However, occlusion to a branch or distal portion of the retinal artery would lead to less profound loss. Due to supply of the macula by the cilioretinal artery in a small proportion of patients, CRAO may present with a central area of visual sparing.

Natural history

Through experimental studies, we know that the retina may survive for approximately 90-100 minutes following ligation. Therefore, CRAO is an ophthalmic emergency that needs urgent treatment.

Untreated, spontaneous clinical improvement is rare. The severity of visual loss depends on the presentation. Severely affected patients are usually left with only a small island of temporal vision that can detect counting fingers at best without intervention. Those with branch occlusion usually recover normal vision completely (~80%). Discussed below.

Clinical features

The hallmark of CRAO is sudden onset, painless loss of vision.

Symptoms

- Acute, painless visual loss: Loss is typically severe, patients may only see hand movements.

- Unilateral: Bilateral involvement is extremely rare simultaneously. However, sequential occlusion may occur.

- Central visual sparing (15-30%): May suggest patent cilioretinal artery.

Signs

- Relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD): Asymmetrical pupillary reaction to light due to optic nerve disease.

- Pale retina

- ‘Cherry red spot’: Suggestive macular sparing due to patent blood supply via the cilioretinal artery.

- Retinal emboli: May be seen in up to 40%.

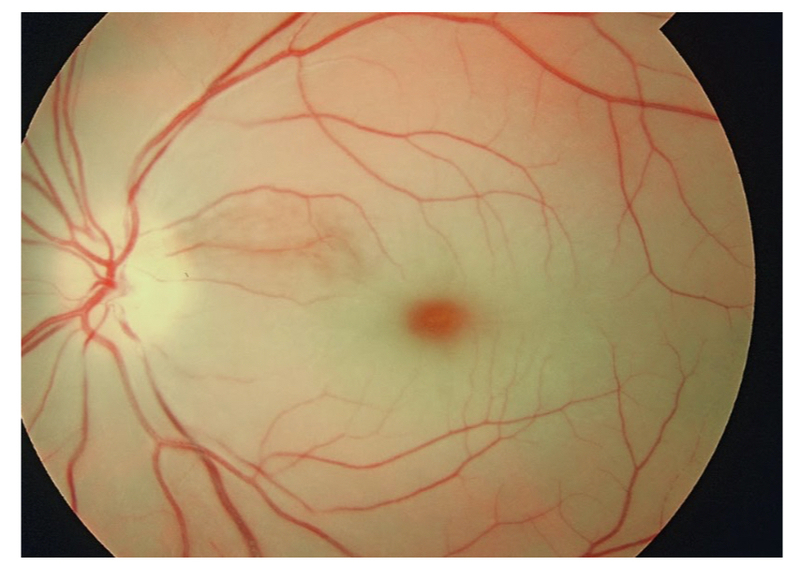

Pale retina secondary to CRAO with 'cherry red spot'

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons

Diagnosis

CRAO is usually a clinical diagnosis based on sudden onset visual loss and classical retinal findings on examination.

The diagnosis of CRAO can be made clinically based on the presence of sudden onset visual loss, ischaemic appearance to the retina on ophthalmoscopy and presence of cardiovascular risk factors.

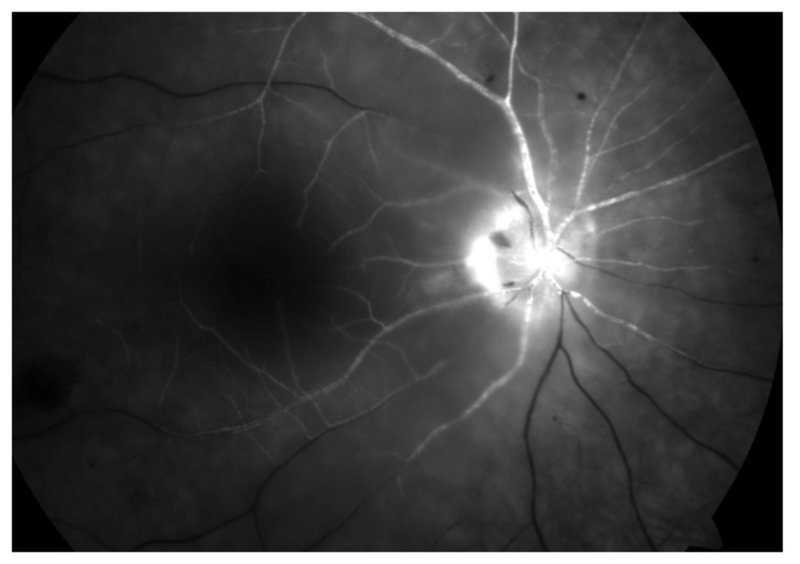

If needed, the diagnosis can be confirmed using fluorescein angiography. During this procedure fluorescent dye is inserted intravenously. This allows assessment of the retinal vessels using imaging. In CRAO there is usually evidence of slowed flow or a filling defect.

Fluorescein angiogram with poor filling of retinal vessels due to CRAO

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons

In the work-up of CRAO, it is critical to exclude GCA. This is because treatment with steroids in GCA can be sight-saving. It should be considered in older patients (> 50 years) with raised inflammatory markers (CRP/ESR) and without visible evidence of embolus on assessment.

Branch retinal artery occlusion

This refers to occlusion of one of the branches of the retinal artery. Typically presents with sudden onset visual loss, which is limited to a single area of the visual field. Less than 50% have reduced visual acuity at presentation.

On examination with an ophthalmoscope or slit-lamp, there is evidence of a limited area of retinal whitening due to ischaemia. An embolus is more likely tho be observed in branch occlusion.

Cilioretinal artery occlusion

This refers to isolated occlusion of the cilioretinal artery that leads to central visual loss. The degree of visual impairment depends on the reliance of the macula on this arterial blood supply.

Management

Ideally, treatment should be administered within 6 hours of onset to be effective.

The evidence supporting acute treatment of CRAO is limited. Treatment is usually attempted within 24 hours of presentation, but should be completed within 6 hours to improve efficacy.

The exception to this is the identification of GCA, which should be treated urgently with high-dose steroids (usually intravenous methylprednisolone). Steroids have a significant effect on outcome.

Intra-arterial thrombolysis

This refers to catheter-directed delivery of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) via the ophthalmic artery. It is being increasingly used as primary treatment in patients without complications who present within an appropriate time frame.

Systemic thrombolysis is associated with more side-effects (e.g. intracerebral haemorrhage) than catheter-directed thrombolysis. Due to the limited efficacy of thrombolysis as a whole in CRAO, the risk of systemic thrombolysis if felt to outweigh the benefit.

Surgical intervention

In patients who are not candidates for thrombolysis but still present within a reasonable timeframe from onset, anterior chamber paracentesis can be completed. This aims to reduce intra-ocular pressure with the hope that it dislodges the embolus.

Other interventions

These are traditional techniques that may be used in patients deemed not suitable for thrombolysis or surgical intervention.

- Ocular massage: direct pressure to eye over a closed eye lid every 10 seconds with 5 second breaks. This aims to alter intraocular pressure in an attempt to dislodge the embolus. Rarely successful.

- Intraocular lowering therapies: acetazolamide, mannitol and topical agents can all be used in an attempt to lower intra-ocular pressure.

- Vasodilator therapies: pentoxifylline and nitroglycerin can be used in an attempt to dilate arterial vessels.

- Hyperbaric oxygen therapy

Long-term management

Patients with CRAO usually have evidence of cardiovascular disease and risk factors. Therefore, following management of the acute episode it is important to investigate these conditions.

- Carotid artery disease: carotid duplex or CT angiography. Carotid endarderectomy may be needed.

- Exclusion of giant cell arteritis: CRP, ESR, temporal artery biopsy.

- Cardioembolic sources: echocardiography, 24 hour tape and electrocardiogram

- Thrombophilia testing: especially in younger patients

Long-term, depending on the suspected aetiology patients may require anti-platelets, statin therapy, anti-hypertensives and lifestyle advice among other interventions.

Branch retinal artery occlusion

Management of branch retinal artery occlusion is usually supportive due to the high chance of spontaneous recovery and no major effective therapies. However, all patients should be referred for urgent ophthalmic assessment if presenting within 24 hours.

It is critical to investigate for the underlying cause and optimise cardiovascular risk factors.

Complications

Even if presenting early, the prognosis of CRAO is still poor with permanent loss of vision in the affected eye.

The main short term complication of CRAO is visual loss, which can be profound. Only around 1-8% of patients will have spontaneous recovery. Patients with CRAO have a three times higher risk of mortality, which likely reflects the overall cardiovascular disease burden.

In patients with some retinal recovery, late ophthalmic complications can occur. The ischaemic retina can cause neovascularisation, which refers to development of new vessels. These vessels may rupture leading to vitreous haemorrhage or occlude the anterior chamber leading to glaucoma.

Last updated: May 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback