Episcleritis and scleritis

Notes

Overview

Episcleritis and scleritis are separate conditions that are due to inflammation of the sclera.

The sclera is the white of the eye that provides structural support and is divided into different layers. Episcleritis and scleritis and two related, but separate, conditions that result from inflammation of the sclera.

- Episcleritis: inflammation of the superficial episcleral layer

- Scleritis: inflammation of the sclera that usually occurs in the anterior portion

Both conditions can lead to a red painful eye, but importantly episcleritis does not progress to scleritis.

Episcleritis is a common, benign, and usually self-limiting condition. It usually resolves within 1-2 weeks and topical lubricants may be used for symptomatic relief. On the other hand, scleritis is rare and potentially destructive without treatment. Scleritis is commonly associated with an underlying autoinflammatory condition (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis) and leads to a more deep, constant, boring pain. Scleritis requires urgent ophthalmic assessment and initiation of systematic treatment (e.g. NSAIDs, corticosteroids.

Sclera

The sclera refers to the whiteness of the eye.

The sclera refers to the white of the eye that provides protection with its tough fibrous layer. It gives the eye structural integrity and enables attachment points for the extra-ocular muscles that control eye movement.

The sclera is divided into different structural layers:

- Episclera: this is a thin loose connective tissue layer, which lies just beneath conjunctiva and contains blood vessels.

- Stroma: this is the main, and thickest, layer of the sclera that is composed fibrosis connective tissue. This provides the strength and rigidity of the sclera.

- Lamina Fusca: this is a thin pigmented layer located beneath the stroma that contains melanocytes.

The main bulk of the stroma is avascular. It maintains its metabolic requirements by diffusion from the overlying episclera and underlying choroid that are both highly vascular. Posteriorly, the sclera fuses with the dura mater of the optic nerve. The sclera is divided into an anterior and posterior portion:

- Anterior: visible to the naked eye

- Posterior: non-visible, lying behind the globe

NOTE: over 90% of cases of scleritis involve the anterior portion that results in the characteristic visible features of a red painful eye.

Epidemiology

Episcleritis is a relatively common condition whereas scleritis is rare.

The true incidence and prevalence of episcleritis is difficult to ascertain because it is often mistaken for other diagnoses (e.g. conjunctivitis). It is more common in females, mostly occurs in young and middle-aged adults, and may be bilateral in up to 50% of cases.

Scleritis may be isolated, but up to 50% of cases are associated with an underlying autoimmune condition (e.g. connective tissue disease or vasculitis). Scleritis is most commonly associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Similar to episcleritis, it is more common in middle aged-adults with a female predominance.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

Inflammation of the sclera can be mediated by a variety of immune-related mechanisms.

Episcleritis

Episcleritis refers to inflammation of the episcleral layer that is commonly due to dry eye syndrome. This refers to inadequate lubrication of the eye(s) with tears. There are two types of episcleritis:

- Simple: sectorial inflammation confined to a specific segment of the episclera, but in some cases may be more diffuse.

- Noduler: raised inflammation of the episclera confined to a specific segment.

The majority of cases of episcleritis are isolated and not associated with an underlying condition. However, it can be associated with an underlying disease in up to 30% of cases. These can include rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, vasculitis, and SLE among others.

Scleritis

Scleritis is commonly associated with an underlying autoinflammatory disorder but the exact mechanisms leading to scleral inflammation remain unclear. There seems to be an association with underlying blood vessel inflammation (i.e. vasculitis). Scleritis is predominantly anterior in over 90% of cases and can be divided into different types:

- Diffuse: most common form associated with widespread inflammation of the anterior sclera. Usually responds to treatment and rarely recurs.

- Nodular: second most common form. Associated with nodular inflammation of the sclera.

- Necrotising: least common but more likely to be associated with an underlying disorder and lead to profound ocular complications including severe pain, scleral thinning, and loss of vision. Divided into necrotising associated with inflammation (typically very painful) and scleromalacia perforans (typiclaly limited symptoms due to necrosis of nerve fibres).

Approximately 10% of scleritis cases are posterior, which is harder to detect due to the absence of anterior visual symptoms (e.g. red eye). This often leads to a delay in diagnosis with pain that is difficult to locate and visual loss due to optic nerve involvement.

Clinical features

Scleritis and episcleritis are both characterised by the presence of an uncomfortable or painful red eye.

Episcleritis is characterised by rapid onset of a red and uncomfortable eye. Vision is not affected and overt pain is unusual. On the other hand, scleritis has a more subacute onset characterised by a deep boring pain that is worse at night time limiting sleep, and may be associated with headaches, photophobia and visual loss in severe cases.

Episcleritis

- Acute onset

- Uncomfortable, sensation of grittiness, or mildly painful eye

- Bright red episclera: usually in sectorial pattern, but may be diffuse

- Dilatation of the superficial episcleral vessels

- Unilateral or bilateral (~50%)

- Increase lacrimation

- Normal visual acuity

- No thinning of the sclera

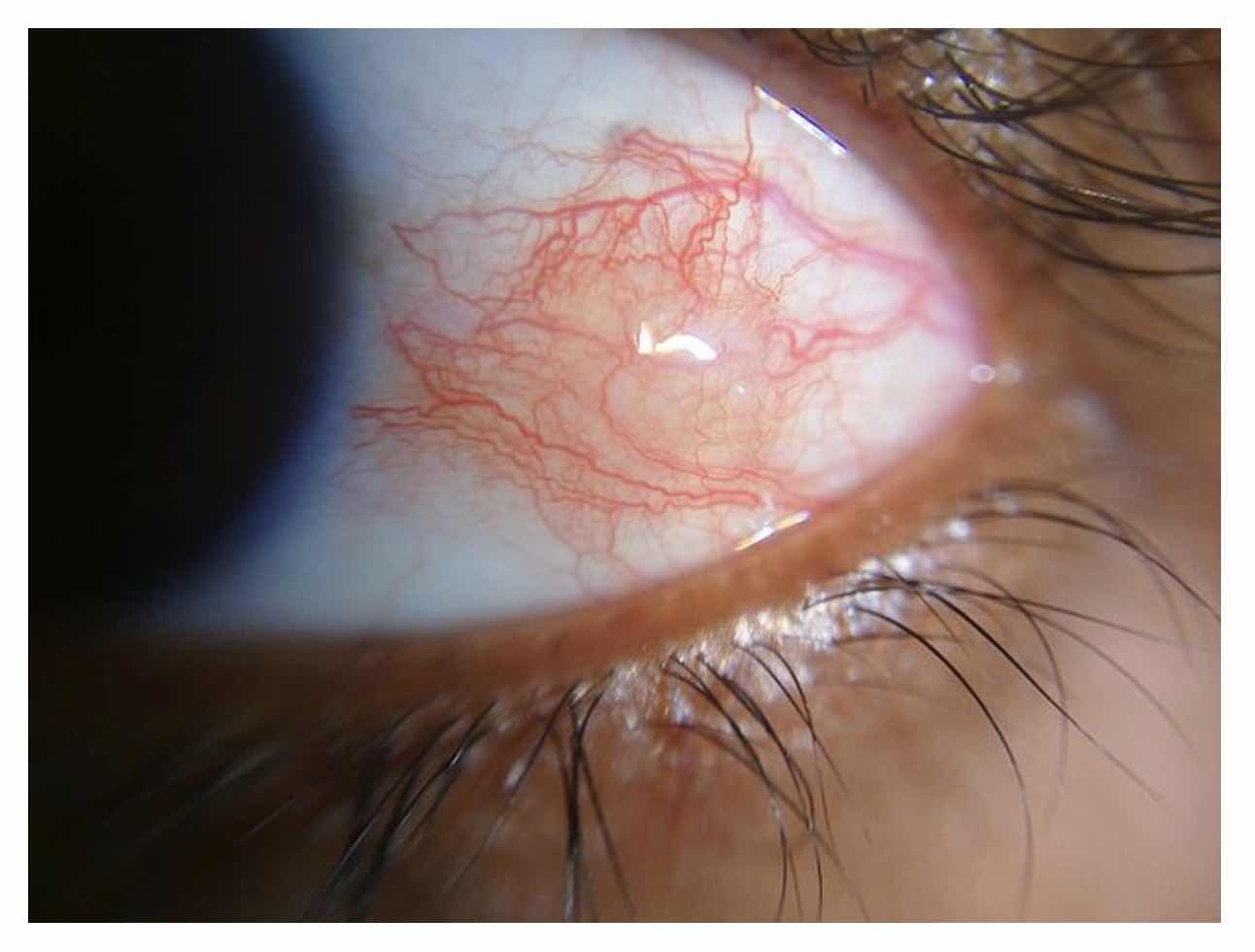

Evidence of sectoral episcleritis.

Image courtesy of Imrankabirhossain (Wikimedia Commons)

Scleritis

- Subacute, gradual onset

- Deep, constant, boring pain: may have radiation to jaw or forehead and usually worse at night

- Ocular redness: may be sectoral or diffuse

- Dilatation of deep episcleral plexus and oedema (slit-lamp examination)

- Unilateral or bilateral

- Increased lacrimation

- Photophobia

- Painful eye movement

- Reduced visual acuity

- Scleral thinning

- Associated symptoms: headache, vomiting, fever

NOTE: the anterior sclera may appear normal in posterior scleritis without anterior involvement. Features suggestive of posterior scleritis include lid oedema, proptosis, swollen optic disc, diplopia, pain on eye movement, and reduced visual acuity.

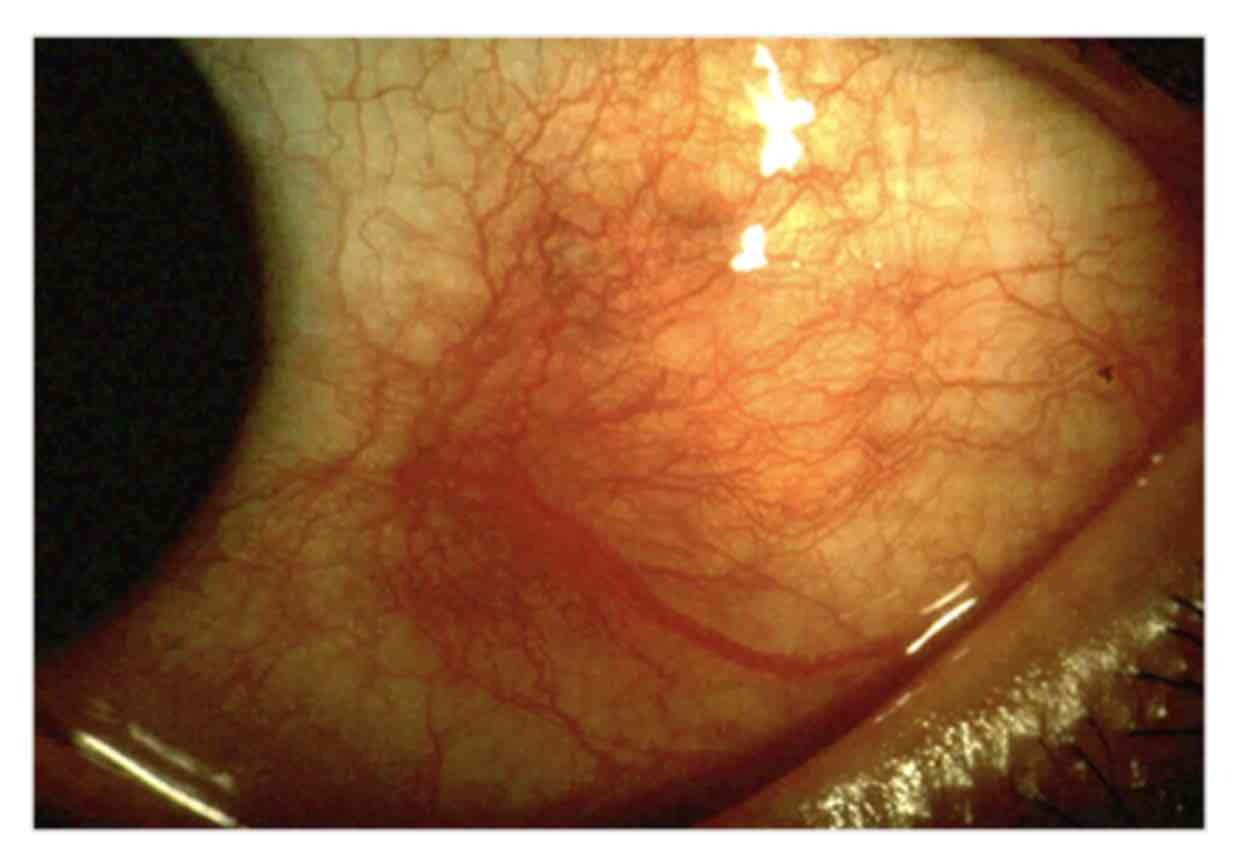

Evidence of scleritis

Image courtesy of Kribz (Wikimedia Commons)

Diagnosis & investigations

A patient with suspected scleritis requires prompt ophthalmic assessment.

The diagnosis of episcleritis can usually be made clinically based on the typical history and examination findings. If the diagnosis is in doubt, the condition is recurrent or symptoms do not resolve, then an ophthalmology referral should be considered. Additional investigations may be required if there is a suspected underlying diagnosis (e.g. rheumatoid or inflammatory bowel disease).

Scleritis is also diagnosed based on characteristic clinical features of a severely painful eye with intense redness of the sclera. If the diagnosis if suspected, it requires prompt ophthalmic assessment. This means referral and assessment within 24 hours of symptom onset. Formal review of the eye will usually reveal scleral oedema and vasodilatation of deep scleral vessels on slit-lamp examination. Other findings during the ocular examination will help to determine the subtype.

There are two important aspects of the ophthalmic assessment:

- Confirm the diagnosis and exclude an alternative diagnosis: this involves a formal slit-lamp examination and may include additional imaging on a case-by-case basis (e.g. B-scan ultrasonography, cross-sectional imaging with CT/MRI).

- Evaluation for an underlying systemic disease: this involves taking a formal history and examination, completing basic investigations (e.g. FBC, U&E, LFT, CRP), and then completing special serological tests as part of a connective tissue disease screen (e.g. ANCA, Anti-CCP, anti-dsDNA) with targeted imaging studies (e.g. chest x-ray, CT-PET).

Management

Episcleritis is usually a benign condition that improves without treatment over 7-10 days.

Episcleritis is usually a self-limiting condition that improves over 1-2 weeks without specific treatment. If symptoms are particularly problematic, topical artificial tears / lubricants can be used with many over the counter preparations available. This is especially useful for patients with episcleritis secondary to dry eyes. When symptoms are particularly troublesome, additional agents may be used but this should be guided by a specialist. Options may include topical NSAIDs, oral NSAIDs, and topical steroids.

Scleritis can be a sight-threatening condition and treatment depends on the severity and subtype. Scleritis that is secondary to a non-infective cause (e.g. autoimmune condition or idiopathic) will require treatment with NSAIDs, steroids, and/or other systemic immunosuppressive therapies. Patients with necrotising or posterior scleritis usually require more aggressive treatment regimens. Treatment of scleritis is specialist and should be guided by an ophthalmologist. Options can include:

- Oral NSAIDs

- Oral corticosteroids (e.g. prednisolone at high dose)

- Immunosuppressive agents (e.g. cyclophosphamide)

- Biologics (e.g. rituximab)

Treatment of scleritis may need to be directed at both the eye and underlying systemic disease if present. This will involve close collaboration between ophthalmology and rheumatology.

Prognosis

The majority of patients with episcleritis have a mild isolated episode, but recurrence can occur.

Episcleritis is usually self-limiting with excellent prognosis and most complications are treatment-related. On the other hand, scleritis can lead to significant morbidity including visual loss, which is more common in patients with necrositing or posterior scleritis subtypes (seen in up to 85%). Complications can occur including cataracts, glaucoma, and corneal damage.

Last updated: July 2023

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback