Open-angle glaucoma

Notes

Introduction

Glaucoma refers to a collection of disorders resulting in progressive optic neuropathy in which raised intraocular pressure is typically a key factor.

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a common pathology affecting the eye that untreated can result in significant loss of vision. Worldwide it is the leading cause of irreversible blindness with 66 million affected, 12.5 million of whom are blind. In the UK it is responsible for around 10% of those registered blind. There are two major forms of glaucoma (and a related condition ocular hypertension):

- Open-angle glaucoma: Characterised by a normal angle between the iris and cornea. It is divided into primary and secondary forms. Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common form of glaucoma. Raised intra-ocular pressure (IOP) is normally but not invariably present, some with POAG have ‘normal pressure glaucoma’.

- Angle-closure glaucoma: Characterised by a closing or narrowing of the angle between the iris and cornea. Again may be split into primary and secondary forms, though primary is far more common. The closure of the anterior chamber angle results in reduced drainage of the aqueous humour and rising IOP.

- Ocular hypertension: Refers to elevated IOP without the presence of other changes seen in glaucoma. May represent an opportunity to offer early treatment and prevent the development of visual loss. IOPs greater than 21 mmHg are generally said to be raised.

Open-angle glaucoma

In this note we will focus on the chronic form of primary open-angle glaucoma. POAG is by far the most common form of glaucoma. Its pathogenesis is poorly understood and onset often insidious.

When diagnosed, treatment typically involves topical therapies (e.g. topical beta blocker or prostaglandin analogue).

Epidemiology

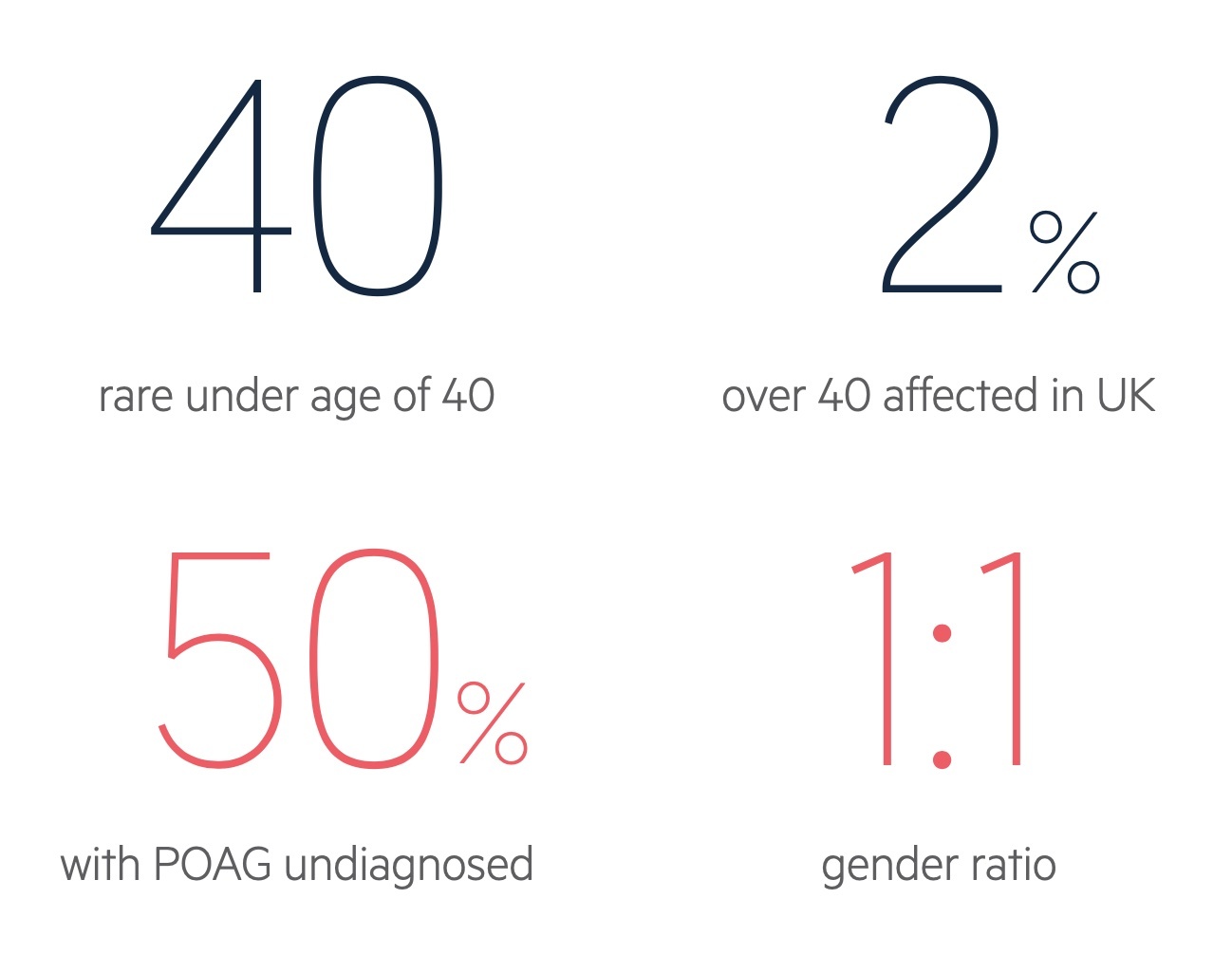

POAG affects around 2% of adults over the age of 40 in the UK.

Prevalence increases with advancing age with an estimated 8% of those aged 80 years affected. The gender ratio is balanced and it is more common in those of African heritage. Importantly the condition is thought to go unrecognised in up to 50% of people.

Risk factors

A number of risk factors have been associated with the development of POAG.

- Age

- Afro-Caribbean heritage

- Raised intra-ocular pressure

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Family history

- Myopia

Aqueous humour

Aqueous humour is produced by epithelium covering the ciliary bodies in the posterior chamber of the eye.

Basic anatomy

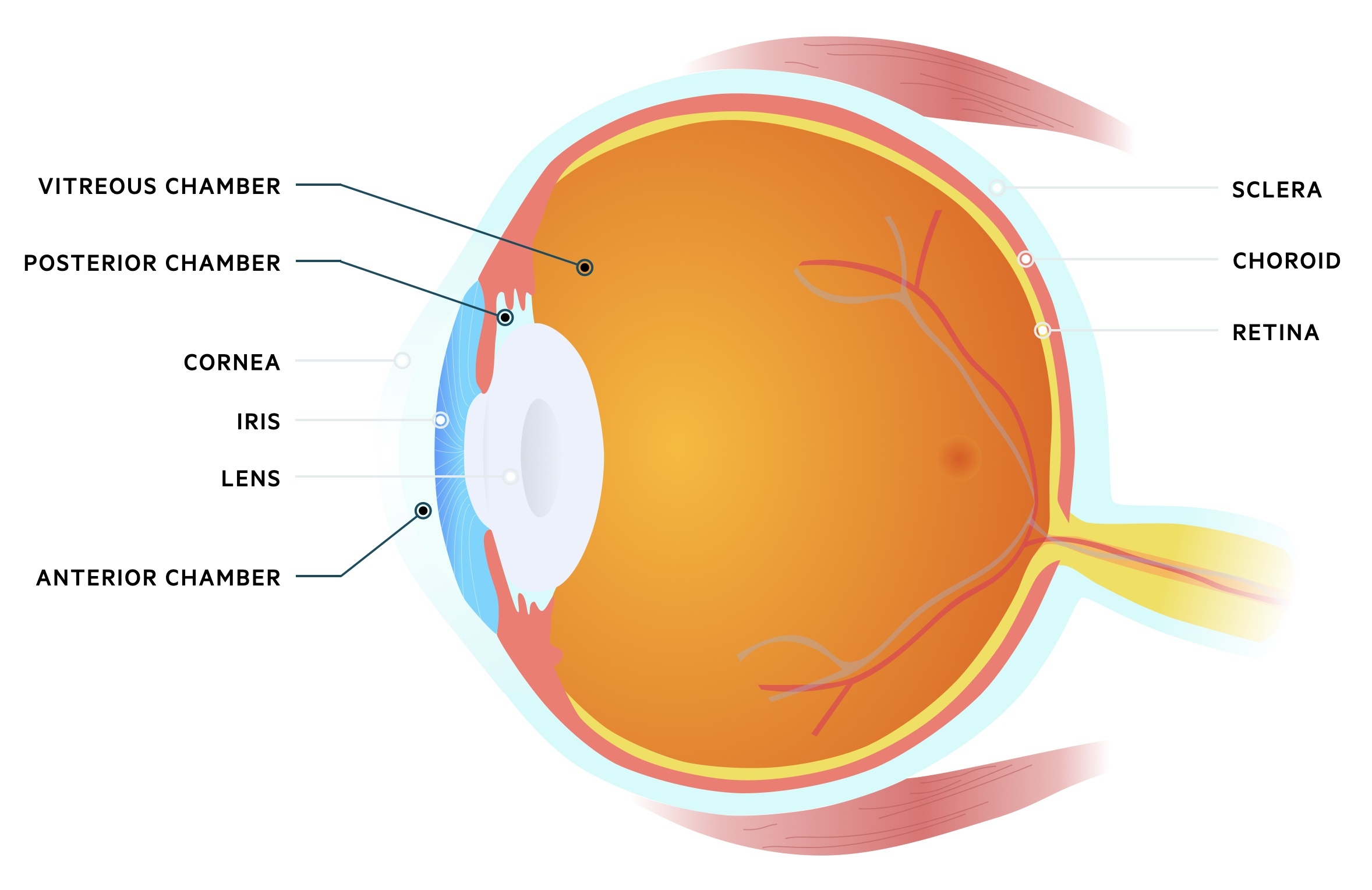

The eye may be divided into three chambers:

- Anterior chamber: Located anteriorly between the cornea and iris. Filled with aqueous humour that flows from the posterior chamber.

- Posterior chamber: Located behind the anterior chamber, between the iris and lens. Aqueous humour is produced here by the ciliary epithelium.

- Vitreous chamber: Located behind the posterior chamber between the lens and back of the eye. Filled with vitreous humour, a fluid with gel-like consistency.

Production & drainage

The aqueous humour is produced and actively secreted by the ciliary epithelium located in the posterior chamber of the eye. It is a watery fluid with a similar make-up to plasma though with a far lower protein content.

NOTE: Inflammation of the uvea can lead to increased membrane permeability and therefore protein content in the aqueous humour. This can scatter light resulting in flare.

The aqueous humour passes through the pupil into the anterior chamber and drains at the anterior chamber angle (iridocorneal angle). There are two drainage pathways:

- Canal of Schlemm: The majority of aqueous humour drains via the trabecular meshwork into the canal of Schlemm.

- Uveoscleral pathway: Some of the aqueous humour may drain via the ciliary muscle into the supraciliary and suprachoroidal spaces.

Aetiology & pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of POAG remains unclear.

Primary open-angle glaucoma

The pathogenesis of POAG is poorly understood. Raised IOP appears central too many cases though it is disputed as to whether this occurs due to increased production, reduced drainage, anatomical differences or a combination of factors.

Loss of axons of the optic nerve may occur due to elevated IOP. Other factors may also predispose individuals to this with a mix of systemic (e.g. microcirculatory damage) and genetic factors implicated.

Secondary open-angle glaucoma

Secondary open-angle glaucoma is relatively rare and normally occurs due to reduced drainage of aqueous humour and raised IOP. They occur secondary to defined processes, a few of these are described below:

- Neovascular glaucoma: Neovascularisation that occurs due to ischaemia (e.g. microcirculatory damage in diabetic retinopathy) and impairs drainage of the aqueous humour.

- Pseudoexfoliative glaucoma: Deposits of pseudoexfoliative material in the trabecular meshwork impairs drainage of the aqueous humour.

- Pigmentary glaucoma: Deposits of pigment (from the iris) in the trabecular meshwork impairs drainage of the aqueous humour.

- Uveitic glaucoma: Secondary to uveitis where inflammation leads to reduced outflow of aqueous humour.

- Glucocorticoid-induced glaucoma: In some patients corticosteroids increase resistance to drainage of the aqueous humour. It is most common with topical drops but may occur with any preparation of corticosteroids.

Diagnosis

POAG is asymptomatic until the late stages of disease.

Patients with POAG are largely asymptomatic. Though visual loss may occur, central vision is preserved until late in the disease. The peripheral visual loss often goes unnoticed and the other eye may somewhat compensate for the defect.

Diagnosis is therefore typically made during routine ophthalmic examination at optometrists. GP’s may also suspect the diagnosis after visualising ‘cupped discs’ during ophthalmoscopy. Formal ophthalmic review will include:

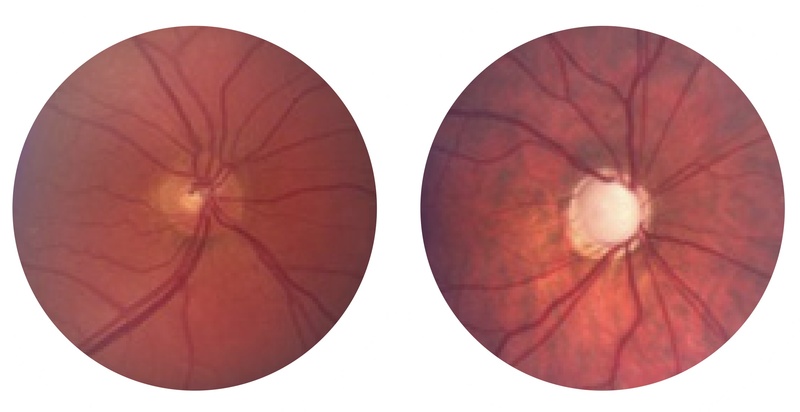

- Ophthalmoscopy: The appearance of the optic disc shows progressive ‘cupping’ in glaucoma. This refers to an increase in the optic disc that is taken up by the central ‘cup’.

- Visual fields: Depending on the stage of the disease variable amounts of visual loss may be found on assessment of the visual fields. Carried out with machines like the Humphrey visual field analyser.

- Intraocular pressure: A normal IOP ranges from 8 - 21 mmHg. Elevation is common in open angle glaucoma but it is key to note that not all patients with glaucoma will have elevated IOP.

- Gonioscopy: Allows assessment of the anterior chamber and the internal drainage system.

- Central corneal thickness: Pachymetry allows for the assessment of a patients corneal thickness. This can help to contextualise IOP readings which vary depending on corneal thickness.

Normal disc left, disc with 'cupping' characteristic of glaucoma right

Images courtesy of Glaucoma.org

Opportunistic testing

There is no formal screening programme for glaucoma.

At present, a formal screening programme for primary open-angle glaucoma is not recommended within the UK. This is due to two reasons:

- Clear evidence for a sufficiently accurate screening test is not available

- Clear evidence for improved outcomes with screening compared to current care is not available

Despite this, there are several signs indicative of glaucoma that may be picked up. Within the NHS, free eye tests including assessment for Glaucoma may be offered in certain groups:

- Elderly: ≥ 60 years old

- Known diagnosis: diagnosed with diabetes or glaucoma

- Family history: ≥ 40 years old and first-degree relative affected by glaucoma

Management

Treatment is aimed at preventing visual loss.

Management of glaucoma is guided by ophthalmologists, each patients findings are reviewed to help decide upon management. Treatment is generally targeted at reducing IOP, a number of the options are discussed below:

- Topical prostaglandin analogue (e.g. Latanoprost): These reduce IOP, an effect achieved by increased uveoscleral outflow. There are a number of contraindications including pregnancy and breast feeding. Caution must be used in those with COPD/Asthma. Adverse effects include brown pigmentation of the iris, pigmentation of peri-ocular skin and local irritation.

- Topical beta-blocker (e.g Timolol): These reduce IOP by lowering the production of aqueous humour. Caution must be used in those with COPD/Asthma. Local irritation is common, systemic effects may occur and reflect those of beta-blockers.

- Topical sympathomimetics (e.g Brimonidine tartrate): These reduce IOP by lowering the production of aqueous humour and increased uveoscleral outflow. There are a number of cautions and contraindications including pregnancy and breast feeding. Local irritation, dry mouth and an unpleasant taste are relatively common.

- Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g topical - Acetazolamide, topical - Brinzolamide): These cause a reduction in the secretion of the aqueous humour. There are a huge number of adverse effects, cautions and interactions.

- Topical miotics (e.g. Pilocarpine): Induce miosis which ‘pulls’ the iris away from the trabecular meshwork allowing for improved outflow of aqueous humour. Adverse effects include local irritation, myopia, vitreous haemorrhage and retinal detachment.

First line

Generally NICE advise treatment in patients with suspected chronic open angle glaucoma and an IOP of 24mmHg or greater. For these patients and patients with chronic open angle glaucoma a topical prostaglandin analogue (e.g. Latanoprost) is normally used as first line therapy.

In patients with advanced disease surgery with pharmacological augmentation (Mitomycin C) may be offered.

Second line

In those in whom IOP is not reduced enough with topical prostaglandin analogues (and good adherence) to prevent progressive visual loss, the following may be considered:

- A drug from another class:

- A topical beta-blocker

- A topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor

- A topical sympathomimetic

- Laser trabeculoplasty

- Surgery with pharmacological augmentation (Mitomycin C)

Last updated: June 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback