Uveitis

Notes

Overview

Uveitis refers to inflammation of the middle layer of the eye known as the uvea that includes the iris, choroid, and ciliary body.

Uveitis refers to a group of conditions that cause inflammation of the pigmented middle layer of the eye known as the uvea. There are different types of uveitis depending on the area of the uvea affected which may be unilateral or bilateral. Anterior uveitis is the most common form, which classically causes a painful red eye, whereas posterior uveitis more typically causes visual changes, floaters, and flashing lights.

Patients with suspected uveitis should be referred to an ophthalmologist urgently for assessment within 24 hours. The diagnosis is usually clinical based on slit-lamp examination and patients will need to be assessed for an underlying systemic autoimmune disease which is present in up to 40% of cases.

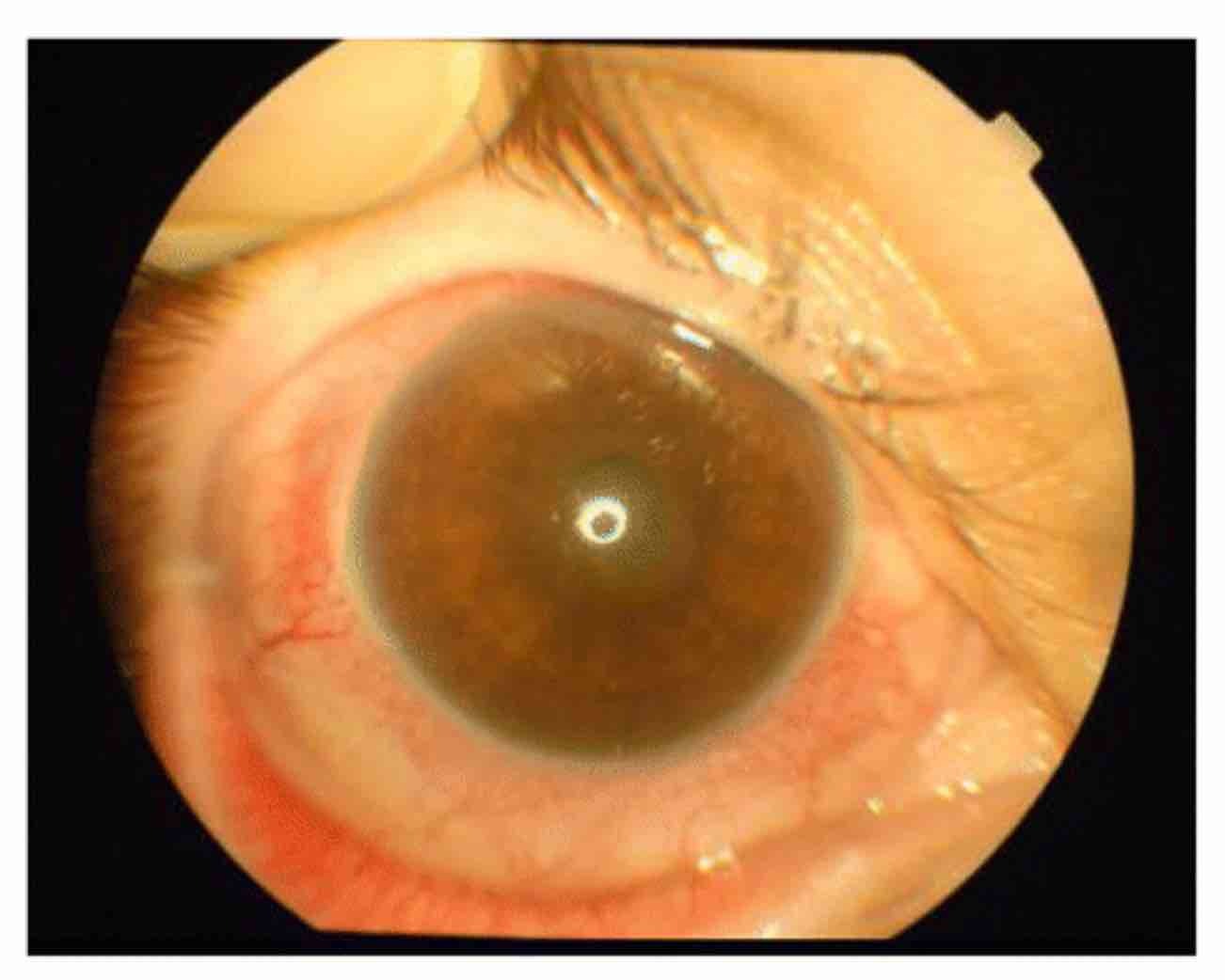

Anterior uveitis of the right eye.

Image courtesy of Duman, R. et al. (Wikimedia Commons)

Uvea

The uvea, or uveal tract, refers to the vascular middle layer of the eye that lies between the sclera and retina.

The uvea is the pigmented middle layer of the eye. It is essential for controlling the amount of light entering the eye, the shape of the lens for accommodation, and providing nourishment to the retina which includes photoreceptor cells.

The uvea is divided into three components:

- Iris: the coloured part of the eye. It controls the size of the pupil which helps regulate the amount of light entering the eye.

- Ciliary body: a ring-shaped structure located behind the iris. It has important functions in accommodation, allowing us to focus on objects at different distances by changing the lens shape. It has several parts including the ciliary muscle, ciliary process, and zonular fibres.

- Choroid: this is a thin, dark brown/black layer that extends from the ciliary body to the optic nerve head. Its dark colour is due to melanocytes in its outermost layer. It contains a network of blood vessels that help support the health of the retina.

Classification

Uveitis is divided into different types depending on the location that is affected.

Uveitis is broadly classified by the area of the uvea that is affected. The anterior portion of the uvea includes the iris and ciliary body. The posterior portion of the uvea is known as the choroid.

The terminology (i.e. descriptors) use to describe uveitis and its subsequent classification is based on the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN). This divides uveitis into anterior, intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis depending on the anatomical structures that are involved. Descriptive terms may then be used to describe uveitis including onset (sudden, insidious), duration (limited, persistent), and course (acute, chronic, recurrent).

Types

Uveitis may be anterior, posterior, or panuveitis. The term intermediate uveitis may be used separately but here we group it with posterior uveitis:

- Anterior uveitis: this is the most common form of uveitis and refers to inflammation of the anterior portion of the uvea. It is characterised by leucocytes in the anterior chamber of the eye. Various terms are used to describe the condition including iritis (inflammation of the iris), and iridocyclitis (inflammation of the iris and adjacent ciliary body). Generally, these terms are used synonymously with anterior uveitis.

- Posterior uveitis: this refers to inflammation in the posterior portion of the uvea. It is characterised by leucocytes in the vitreous humour and inflammation of the retina and/or choroid. There are various terms that can be used to describe posterior uveitis depending on the extent of inflammation and the structures involved including vitritis, pars planitis, intermediate uveitis, choroiditis, retinitis, neuroretinitis, retinochoroiditis, chorioretinitis.

- Panuveitis: as the name suggests, this refers to inflammation of both the anterior and posterior portions of the uvea.

Descriptors

Uveitis may be further divided based on the onset, duration, and course of the illness.

Uveitis may be acute, chronic, or recurrent:

- Acute uveitis: typically sudden onset with resolution within three months.

- Chronic uveitis: typically insidious onset with symptoms beyond three months or prompt relapse if treatment is discontinued.

- Recurrent uveitis: repeated episodes of inflammation that are interspersed with episodes of treatment-free remission for ≥3 months.

Epidemiology

Anterior uveitis is the most common form seen in > 90% of cases in the Western world.

Uveitis can occur at any age but is more common in patients 20-50 years old. The annual incidence of uveitis is estimated at 12 per 100,000 population. However, differences in incidence, prevalence, and gender distribution depend on the underlying cause. Worldwide, uveitis is a major cause of visual impairment, particularly in the developing world.

Aetiology

There are various causes of uveitis, but up to 30% of cases may be idiopathic (i.e. no known cause).

Uveitis may be caused by a range of different pathologies. These are broadly divided into three main categories:

- Infectious

- Systemic inflammatory diseases

- Uveitis syndromes restricted to the eye (i.e. absence of systemic involvement)

Infectious

A variety of different infectious organisms may lead to uveitis. The clinical presentation is often typical of the underlying pathogen, but the development of infective uveitis depends on multiple factors including host immunity and geography.

Typical infective causes include:

- Bacterial: Cat Scratch disease (i.e. Bartonella), Tuberculosis, Brucellosis

- Spirochetes: Syphilis, Lyme disease, Leptospirosis

- Viral: Cytomegalovirus, Herpes Zoster, Zika virus

- Fungal: Aspergillosis, Histoplasmosis

- Protozoan: Toxoplasmosis

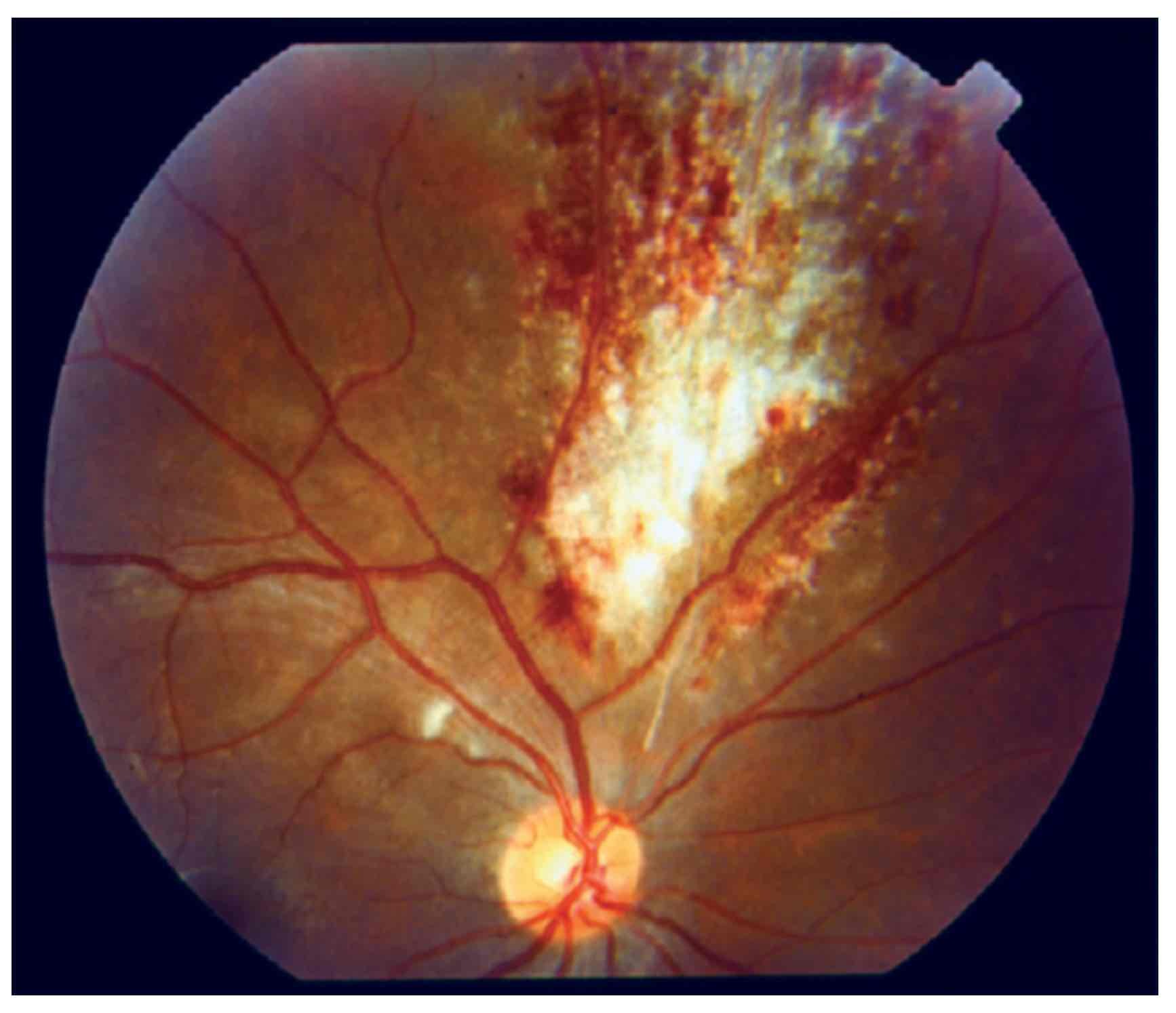

The typical 'pizza pie' appearance of CMV retinitis (posterior uveitis)

Image courtesy of Sudharshan, S. et al. (Wikimedia Commons)

Systemic inflammatory diseases

An underlying systemic inflammatory disorder is identified in around 40% of patients with uveitis. Classically, anterior uveitis is associated with a group of conditions known as spondyloarthropathies, which includes Ankylosing Spondylitis. Anterior uveitis is seen in 20-40% of patients with these conditions, which is associated with the human leucocyte antigen HLA B27 (see pathophysiology).

Many inflammatory disorders are associated with uveitis including:

- Spondyloarthropathies

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Sarcoidosis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Relapsing polychondritis

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- Drug reactions (e.g. Rifabutin, Fluoroquinolones)

Uveitis syndromes restricted to the eye

This refers to conditions that cause uveitis usually in the absence of systemic features. Systemic features are typical of an infective or inflammatory syndrome. Examples include:

- Pars planitis: inflammation of the pars plana, which is part of the ciliary body.

- Birdshot chorioretinitis: a chronic posterior uveitis strongly associated with HLA-A29.

- Sympathetic ophthalmia: bilateral uveitis following eye injury.

- Post-traumatic inflammation (e.g. after cataract surgery).

- Idiopathic

Mimics

Several conditions may give rise to the suspicion of uveitis due to the presence of leucocytes in the anterior chamber (a hallmark of anterior uveitis). The presence of cells in the absence of inflammation is typical of an underlying haematological process (e.g. lymphoma, leukaemia).

Pathophysiology

Anterior uveitis is characterised by inflammation in the anterior chamber that can lead to the formation of a hypopyon.

The exact mechanisms leading to uveitis are not well understood and depend on the underlying aetiology. In infective causes, there may be direct intra-ocular damage or secondary effects due to the release of exo- or endotoxins that result in the recruitment and infiltration of immune cells leading to ocular damage. In inflammatory causes, there is thought to be an abnormal response to ocular antigens leading to an autoimmune response that promotes tissue damage.

Immune infiltration

The infiltration of immune cells that promote and propagate the inflammatory response causes the characteristic finding of 'cells and flares'. This refers to leucocytes floating within the aqueous humour of the anterior chamber (cells) and a foggy appearance due to an increase in protein concentration (flare). In significant inflammation, these cells may precipitate to form a fluid level known as a hypopyon.

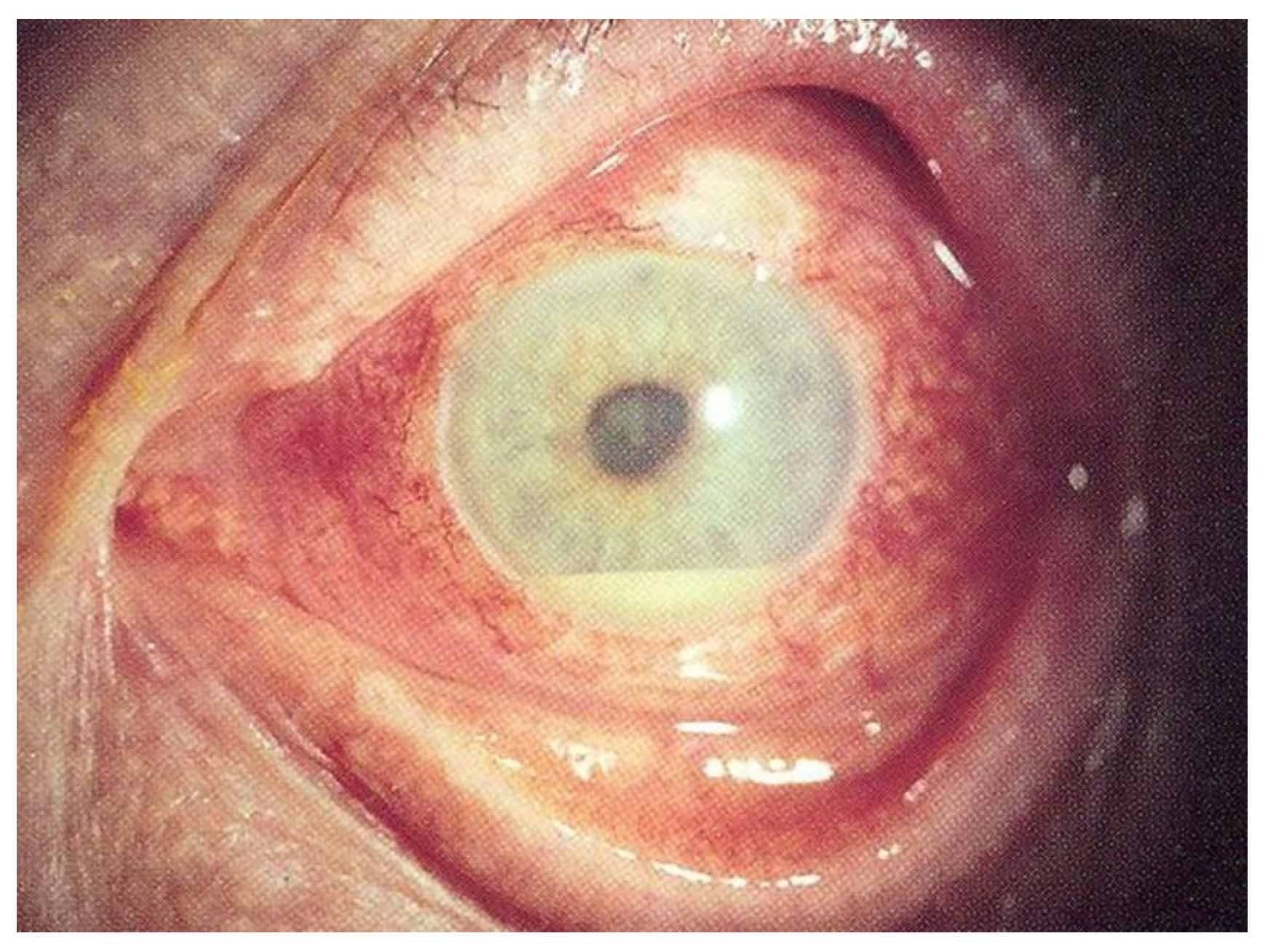

Hypopyon

Image courtesy of EyeMD (Wikimedia Commons)

Genetic susceptibility

Patients with the human leucocyte antigen HLA-B27 are at an increased risk of developing anterior uveitis. HLA-B27 is a type of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule that is involved in the regulation of the adaptive immune response through the presentation of intracellular peptides to immune cells. HLA-B27 is a specific allele that is particularly common in Caucasians (5-6% prevalence). Approximately 50% of all patients with anterior uveitis have the HLA-B27 allele, although the risk of anterior uveitis in patients with HLA-B27 is only 1% across a lifetime. This means that other factors are implicated in its development.

Clinical features

Anterior uveitis is characterised by a painful, red eye that is predominantly located around the limbus.

The symptoms of uveitis depend on the underlying cause and the area of the uvea that is affected. Infectious and inflammatory causes are likely to present with additional systemic features (e.g. joint pain, fever, rash). Anterior uveitis is characterised by pain and redness, whereas posterior uveitis presents with more non-specific visual symptoms such as floaters and visual disturbance.

Uveitis may be unilateral or bilateral. For example, anterior uveitis associated with spondyloarthropathy is commonly unilateral, whereas uveitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease is frequently bilateral.

Anterior uveitis

- Red eye: predominantly located around the limbus (junction between sclera and cornea)

- Painful eye

- Photophobia

- Epiphora (excessive eye-watering)

- Visual impairment: variable severity

- Constricted pupil

- Posterior synechiae: refers to adhesion between the iris (lying anteriorly) and lens (lying posteriorly)

- Cell and flare: this refers to cells within the anterior chamber and subsequent foggy appearance due to increased protein concentration (seen on slit-lamp)

- Hypopyon: fluid level of white cells within the anterior chamber. This is a sign of severe inflammation

Posterior uveitis

- Painless

- Floaters

- Photopsia (flashing lights)

- Visual impairment

- Leucocytes in the vitreous humour (seen on slit-lamp)

- Chorioretinal inflammation (seen on slit-lamp)

Diagnosis & investigations

Patients with suspected uveitis should be referred for urgent ophthalmic assessment within 24 hours.

The diagnosis of uveitis is usually clinical based on the history, examination, and slit-lamp findings. There are many serious causes of a painful red eye with or without reduced vision. Therefore, patients were red flag signs (e.g. photophobia, visual impairment, severe eye pain, or persistent redness) should be referred for urgent ophthalmic assessment, ideally same-day, but otherwise within 24 hours.

Slit-lamp examination

A formal diagnosis of uveitis requires a slit-lamp examination. This is a non-invasive examination of the eye to assess the eye structures in more detail. It uses a biomicroscope, which emits a thin, intense beam of light to illuminate the anterior segment of the eye that includes the cornea, iris, and lens. Slit lamp indirect ophthalmoscopy may then be used to examine the posterior segment of the eye after pupil dilatation.

Features that support the diagnosis of uveitis on slit-lamp examination include:

- Anterior uveitis: Leucocytes within the anterior chambers (i.e. cell and flare), keratic precipitates (cellular deposits on the corneal endothelium), and posterior synechiae (adhesions between lens and iris).

- Posterior uveitis: chorioretinal inflammation and associated lesions (e.g. spots, whitening, detachment) and leucocytes in the vitreous humour.

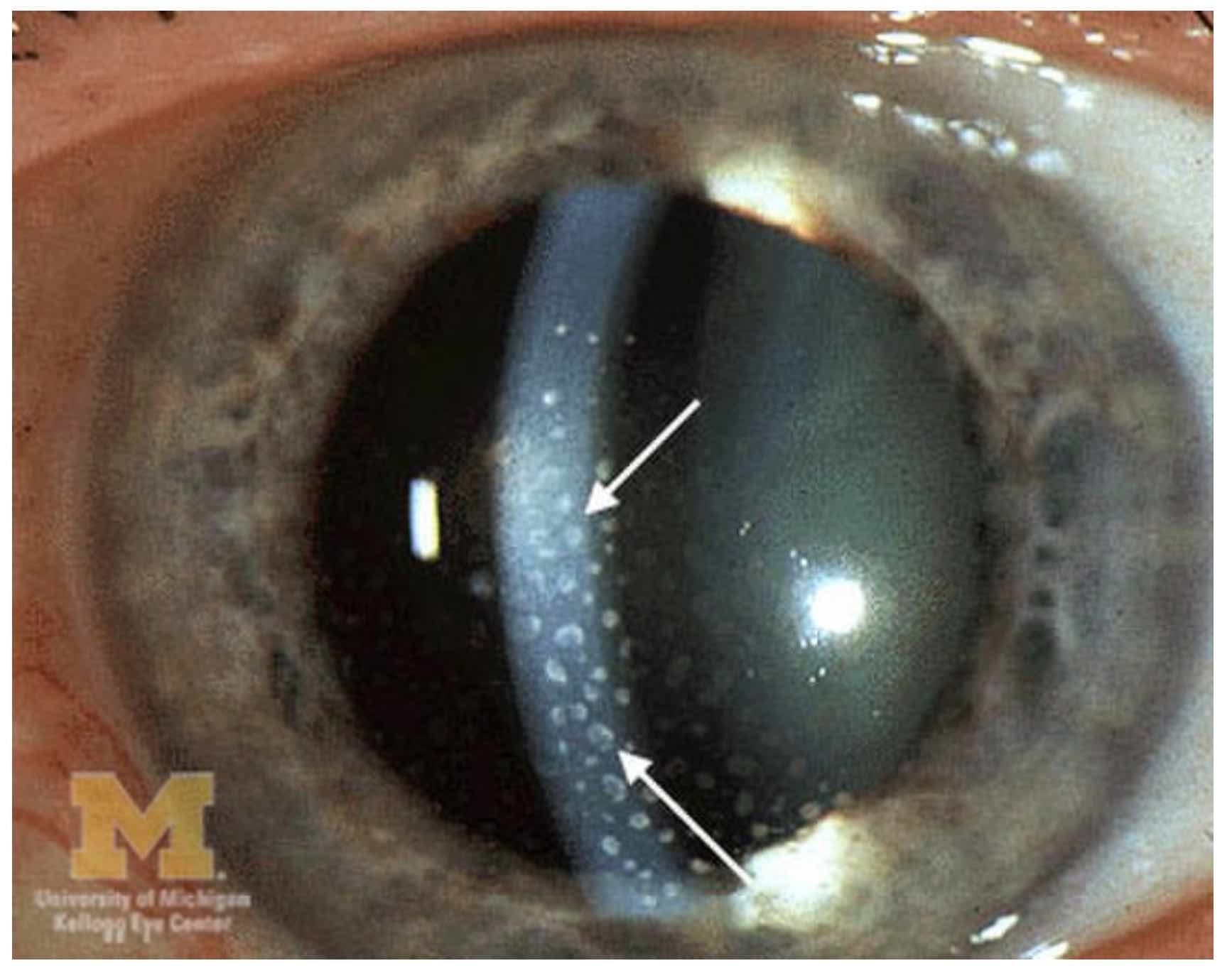

Evidence of keratic precipitates

Image courtesy of Jonathan Trobe (Wikimedia commons)

Work-up for an underlying disorder

Given the association of uveitis with an underlying infective or inflammatory disorder, it is important to undertake a full work-up for a systemic cause. Diagnostic testing, for example, bloods, imaging, and HLA-B27, should be guided by the history and examination findings. Typical investigations that can be done include:

- Routine bloods: FBC, U&E, LFT, CRP

- Connective tissue disease screen: ANA, dsDNA, ANCA, Complement, anti-CCP, Rheumatoid factor, ACE

- HLA typing: HLA-B27

- Infective serological testing: CMV IgM/IgG, HIV, Syphilis, Toxoplasma, Lyme, HSV

- Tuberculosis testing

- Imaging: radiographs/MRI sacroiliac joints (e.g. Ankylosing spondylitis), CT chest (e.g. sarcoidosis)

Management

The predominant treatment of non-infectious anterior uveitis is with topical glucocorticoids.

Uveitis should be managed by an ophthalmologist. In non-infectious causes, the principal treatment of anterior uveitis is with steroids (e.g. Topical prednisolone acetate). However, these can be very dangerous in the context of an alternative diagnosis or infection. Posterior uveitis is usually not responsive to topical agents and may require an intra-ocular corticosteroid injection.

Infective uveitis

The treatment of infective uveitis should be directed toward the underlying cause. For example, anti-viral therapy should be used for patients with suspected herpes-simplex-associated uveitis.

Non-infective uveitis

The principal treatment of non-infective uveitis is corticosteroids. In anterior uveitis, which is more common, the choice is usually topical corticosteroids, whereas posterior uveitis may require an intra-ocular steroid injection. Steroids are generally tapered slowly to avoid rebound inflammation. It is important to recognise that steroids, including topical steroids, can be associated with significant ophthalmic side-effects including raised intra-ocular pressure and cataracts

Patients with resistant or bilateral disease may require early systemic therapy including oral corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressive agents (e.g. methotrexate or anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy).

Other treatment options

Topical agents to paralyse the ciliary body may be used to help relieve pain and prevent the formation of adhesions (i.e. posterior synechiae). These drugs such as cyclopentolate 1% or atropine 1% are anti-muscarinic agents that dilate the eye (known as mydriatics).

Complications

Chronic uveitis is a major cause of visual impairment.

Good long-term outcomes in patients with uveitis usually depend on the underlying cause, severity and location of inflammation, and degree of visual impairment. Factors such as poor visual acuity at presentation, bilateral involvement, and/or the presence of juvenile idiopathic arthritis are all associated with a worse outcome. Acute anterior uveitis is generally considered to have the best outcome, and chronic, non-infectious, posterior uveitis a much worst outcome.

The main complications associated with uveitis include:

- Visual impairment

- Cataracts

- Posterior synechiae

- Macular oedema

- Glaucoma

- Band keratopathy: precipitation of calcium in the cornea that decreases visual acuity

- Epiretinal membrane: a thin fibrous sheet that can develop on the surface of the macula leading to visual impairment

Last updated: August 2023

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback