Bronchiolitis

Notes

Introduction

Acute bronchiolitis is the most common cause of lower respiratory tract infection in children under the age of 2.

Children typically present with a coryzal prodrome followed by cough, reduced oral intake and possible dehydration, increased work of breathing and on auscultation, crepitations and wheeze.

Infection follows a seasonal pattern peaking during the winter months, and is most commonly caused by the respiratory synctial virus (RSV). Symptoms are usually mild lasting only a few days, but in some cases hospital admission may be required.

Management of bronchiolitis consists of supportive measures such as ensuring adequate hydration and temperature control. In a minority of cases, greater support and hospital admission is required.

Epidemiology

Approximately 75% of cases of bronchiolitis occur in children under the age of 1 and 95% in those under the age of 2.

Although children can usually be managed at home, approximately 3% of affected children require hospital admission, with 1.3 per 1000 infants aged under 1 year requiring paediatric intensive care input. The condition most commonly occurs during the winter months.

Aetiology

Most cases of bronchioloitis occur due to a viral pathogen.

The main viral pathogen is Respiratory Synctial virus (RSV), which is an enveloped single-stranded RNA virus with two subtypes, A and B (subtype A causing the more severe infection). RSV causes over 75% of cases with parainfluenza virus accounting for 10-30% and adenovirus 5-10%. In one third of hospitalised cases, co-infection with two or more viruses can be found, as well as with bacterial infection.

RSV is highly contagious, being spread by droplet infection from nasal and oral secretions. The incubation period is 2-5 days and viral shedding continues for 6-21 days after symptoms develop.

Bronchioles are small airways in the lower respiratory tract that the infection affects, with the consequent inflammatory process causing increased mucus production, bronchial obstruction and constriction, alveolar cell death, air trapping, atelectasis, ventilation-perfusion mismatch and ultimately laboured breathing.

Risk factors

A number of risk factors are associated with bronchiolitis and increased disease severity.

• Age less than 3 months

• Prematurity (particularly under 32 weeks)

• Low birth weight

• Male sex

• Low socioeconomic group

• Parental smoking

• Chronic lung disease/airway anomalies

• Congenital heart disease

• Neuromuscular disorders

• Immunodeficiency

Clinical features

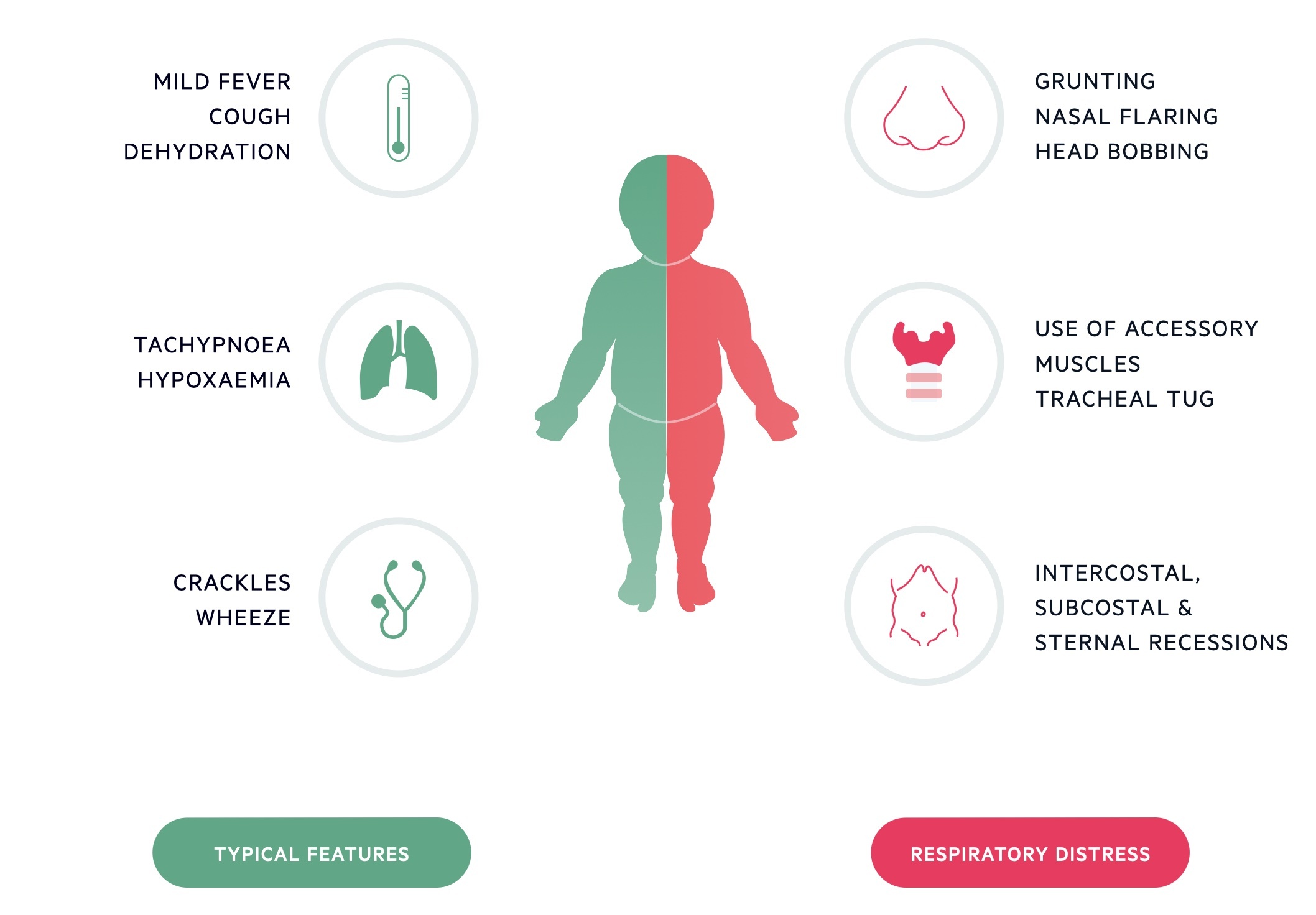

As bronchiolitis affects young infants, clinical manifestations may initially be subtle and difficult to differentiate between other common illnesses.

Common pathologies that may present in a similar manner include upper respiratory tract infection and viral-induced wheeze. The coryzal illness is the initial prodrome with other symptoms usually peaking around days 3-5 of the illness.

Typical clinical features include:

- Apnoea (may be presenting symptom in those < 6 months)

- Low-grade fever

- Coryza and often significant nasal congestion

- Difficulty feeding

- Signs of dehydration

- Tachypnoea

- Use of accessory muscles (nasal flaring, tracheal tug, intercostal and subcostal recessions, abdominal breathing and head-bobbing)

- Fine end-inspiratory crepitations ± wheeze with prolonged expiration

- Hypoxia/cyanosis

Differential diagnosis

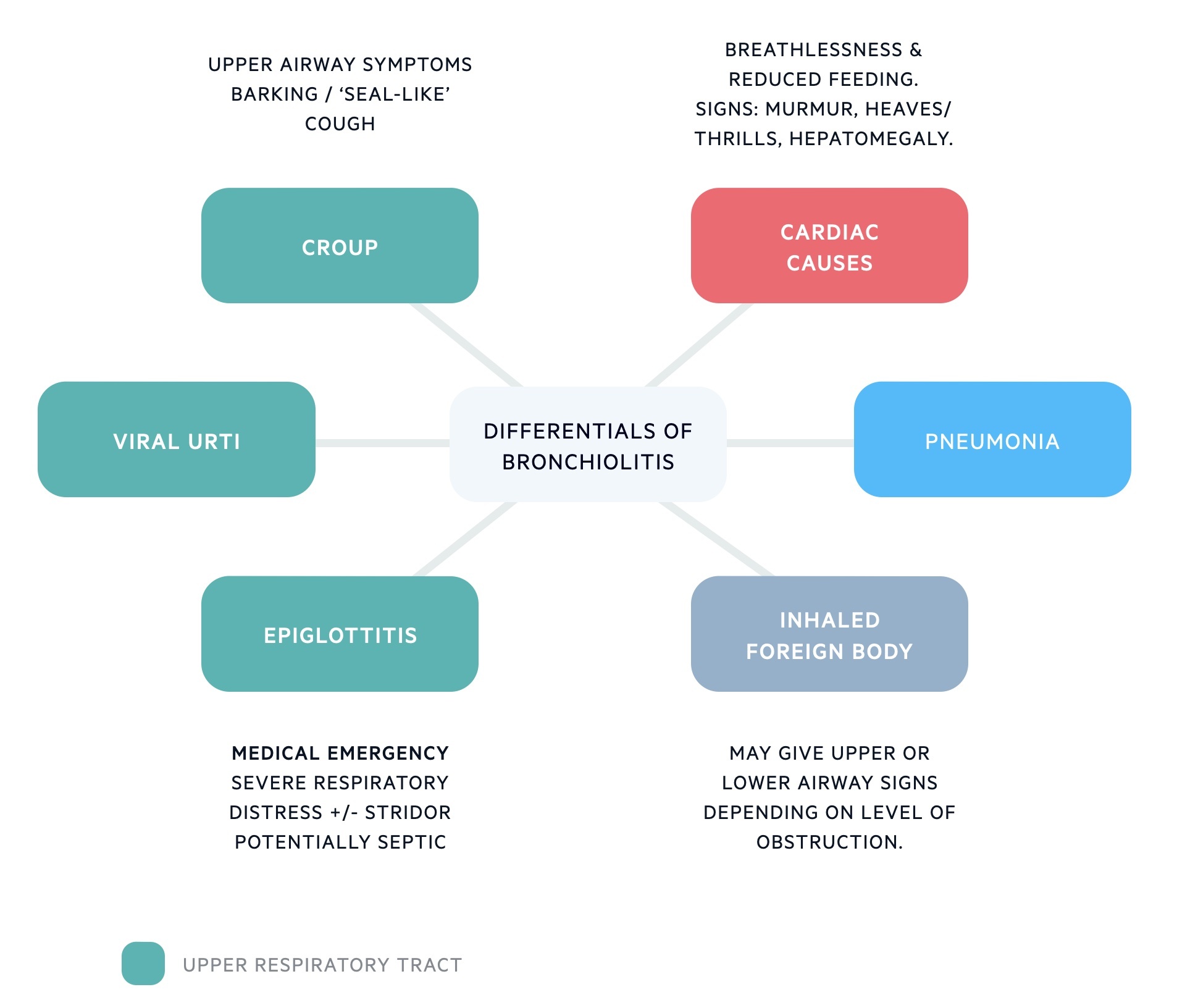

Bronchiolitis is a clinical diagnosis based on classical signs and symptoms in the usual age group.

The most common differentials for bronchiolitis include viral upper respiratory tract infection, viral-induced wheeze/asthma, viral/bacterial pneumonia, foreign body ingestion.

- Viral upper respiratory tract infection: No auscultated chest signs apart from possible transmitted upper airway noises, rarely show signs of increased work of breathing.

- Viral-induced wheeze/asthma: Rare in those under 1 year, usually presents with episodic wheeze only, and more common in those with a personal or family history of atopy.

- Viral/bacterial pneumonia: Toxic appearance, hyperpyrexia (> 39 degrees), persistent focal crepitations.

- Foreign body ingestion: Usually sudden-onset of choking and respiratory distress with no prodrome and possibly unilateral wheeze (typically right-sided due to the increased likelihood of objects passing down right-main bronchus.

Investigations

Bronchiolitis is a clinical diagnosis and viral investigations can be performed on those admitted to hospital.

- Vital signs

- Pulse oximetry

- Viral throat swabs: Rapid viral antigen or nucleic acid amplification testing of nasopharyngeal secretions for RSV and other viruses are usually performed in those admitted to hospital.

Blood tests, blood gas analysis and chest x-rays are not routinely required, and often reserved for children who appear clinically unwell or high-risk of severe infection (see later). Typical x-rays changes include bilateral peri-hilar infiltrates with some hyperinflation due to air-trapping .

Management

Despite the availability of national guidelines for the treatment of bronchiolitis, there is still great variation and controversy among medical professionals regarding the optimal treatment of these patients.

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) have produced guidance promoting supportive care for those presenting with bronchiolitis.

Appropriate cardiorespiratory monitoring is essential including temperature, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, heart rate, and level of consciousness.

Local guidelines often include scoring systems such as the Paediatric Observation Priority Score (POPS) or the Paediatric Early Warning System (PEWS) to help decision-making regarding those who may require admission to hospital or are safe to be discharged home. A POPS < 2 is generally considered to be safe for discharge dependent on clinical assessment.

Supportive care

Supportive care for patients with bronchiolitis may include the following as per NICE guidance:

- General: Children should be made as comfortable as possible (held in a parent's arms or sitting in a position of comfort)

- Anti-pyretics: e.g. paracetamol, ibuprofen if fever causing distress

- Airways: Consider nasal saline drops or nasal/oral suctioning

- Fluids: Maintenance of hydration with oral fluids

- Oxygen: Supplemental humidified oxygen to maintain saturations > 92%

Advanced care

More advanced care in children requiring hospital admission may include:

- Nasogastric or intravenous fluid supplementation.

- Advanced respiratory support with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or mechanical ventilation may be required in children with severe respiratory distress, hypoxia or hypercapnia.

- Early effort to isolate or cohort patients who are confirmed or likely to have RSV infection by commencing standard and contact isolation precautions.

- Antibiotics are not indicated unless bacterial infection is suspected.

Additional therapies

NICE accepts that additional therapies may be considered in children with a history of wheeze, allergies, family history of atopy or who are in severe respiratory distress.

Additional therapies may include:

- Inhaled or nebulised salbutamol

- Ipratropium bromide

- Nebulised adrenaline

- Nebulised hypertonic saline

- Oral or intravenous corticosteroids

- Montelukast

Complications

In most cases, bronchiolitis is a mild and self-limiting condition.

In infants who are immunosuppressed and those with pre-existing heart or lung disease, RSV bronchiolitis can result in any of the following complications:

- Secondary infection

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Chronic lung disease

- Bronchiolitis obliterans

- Congestive heart failure

- Myocarditis

- Arrhythmias

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback