Croup

Notes

Introduction

Croup is a common upper respiratory illness of childhood, which is characterised by a barking cough and inspiratory stridor.

Croup, also known as laryngotracheitis or laryngotracheobronchitis, refers to a specific upper respiratory viral illness that leads to inflammation of the larynx and airways below the glottis (i.e. the part of the larynx that contains the vocal cords).

The classical presentation of croup is a coryzal type illness (i.e. runny nose, nasal congestion, fever) associated with a hoarse voice, characteristic barking cough and stridor. Stridor describes the harsh sound heard on inspiration due to obstruction of the upper airways.

Croup is usually a self-limiting illness, which resolves within three days. However, it can lead to life-threatening upper airway obstruction and respiratory distress.

Epidemiology

Croup is common, affecting 3% of children each year.

Croup most commonly occurs in children aged 6 months to 3 years old and boys are slightly more affected than girls (ration 1.4:1).

Croup can occur all year round, but is most commonly seen in autumn or the early winter period in association with a rise Parainfluenza activity (most common pathogen).

Aetiology

Croup is most commonly caused by Parainfluenza virus.

Croup is caused by a variety of viral pathogens. The most common is Parainfluenza type 1. Other Parainfluenza viruses can cause croup including type 2 in outbreaks (usually milder illness) and type 3 seasonally (usually more severe illness).

Viruses

- Parainfluenza virus (1, 2, 3)

- Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

- Adenovirus

- Human coronavirus

- Others (e.g. Influenza, Metapneumoviruses, Rhinoviruses)

A secondary bacterial infection may complicate croup leading to tracheitis or pneumonia. A secondary infection means the primary infection (in this case viral) has predisposed to a subsequent infection (in this case bacterial). This typically presents as a significant worsening in the illness. Common bacterial pathogens include Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Less commonly, croup may be caused directly by bacteria (e.g. Mycoplasma pneumoniae).

Pathophysiology

Viruses initially infect the nasopharyngeal mucosa and then extend towards the larynx and subglottic airways.

The initial location of infection in croup is the nasopharyngeal airways. Here, the virus multiples and the infection extends distally to affect the larynx and subglottic airways.

Inflammation of larynx and subglottic airways leads to swelling and airway obstruction, which causes the stridorous breathing. The major problem arises due to the cricoid cartilage. This is a complete cartilaginous ring that is unable to expand to counteract the inflammatory process. This leads to significant airway narrowing and respiratory distress.

Direct visualisation of the mucosa of the larynx and subglottic airways during acute croup shows typical inflammation including erythema, swelling, mucosal oedema and exudate (collection of fluid and inflammatory cells).

Clinical features

Croup is characterised by coryzal symptoms, barking cough and stridor.

Croup usually presents with a viral-prodrome of ‘typical’ coryzal symptoms (e.g. runny nose, nasal congestion, dry ‘non-barking’ cough and fever) lasting 12-48 hours. This is followed by a sudden-onset barking cough, respiratory stridor and evidence of respiratory distress, which may be severe.

Signs and symptoms

- Runny nose

- Nasal congestion

- Fever

- Barking cough

- Respiratory stridor

- Hoarse voice

- Respiratory distress (see below)

Respiratory distress

- Tachypnoea

- Grunting

- Nasal flaring

- Tracheal tug

- Retractions: suprasternal, subcostal, intercostal

- Agitation

- Mood changes

- Cyanosis

Diagnosis and differentials

Croup is a clinical diagnosis based on the characteristic signs and symptoms.

Respiratory illnesses are common in children with a wide range of differentials. When considering differentials for croup, think about other causes of airway obstruction that can present in children.

Differentials

- Acute epiglottis

- Bacterial tracheitis

- Foreign body

- Allergic reaction

- Angio-oedema (non-allergic)

- Tonsillitis and peritonsillar abscess

Severity

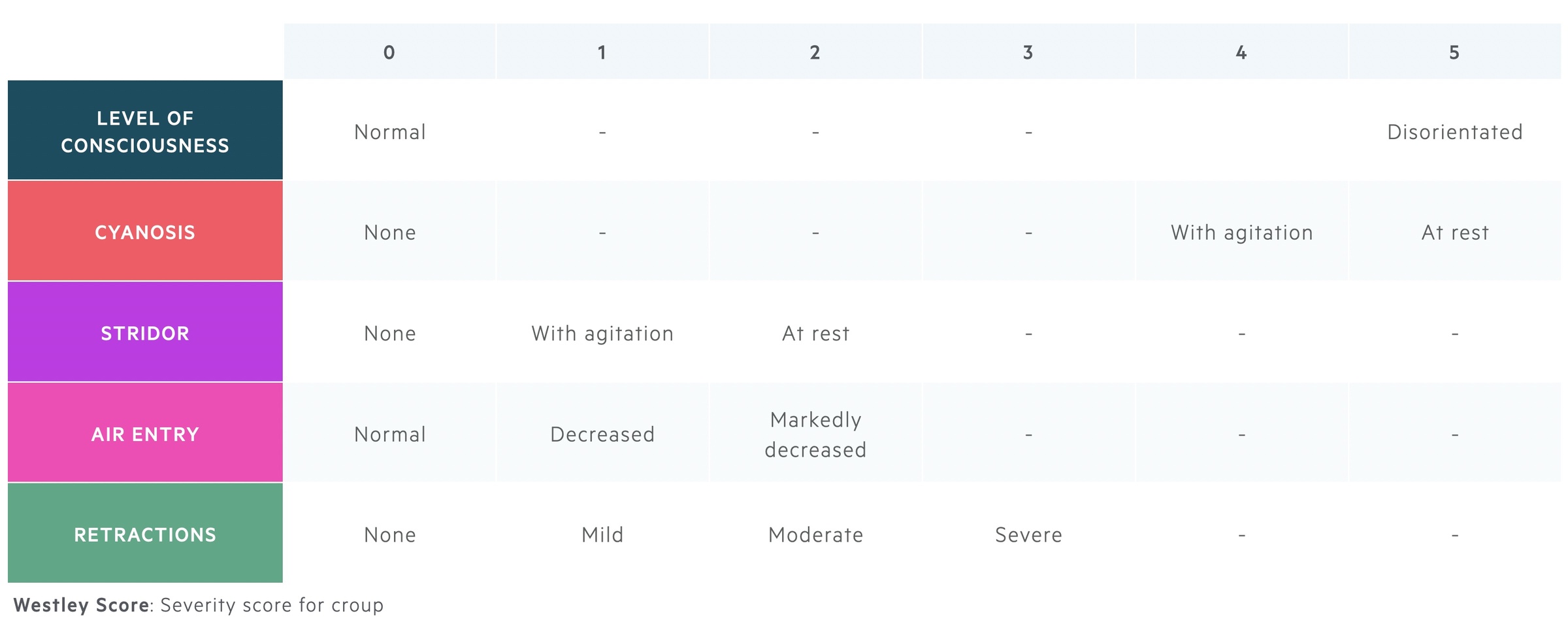

The severity of Croup can be determined using the Westley score, which helps guide treatment.

The Westley score is a clinical scoring system that divides the severity of croup into mild, moderate, severe and impending respiratory failure. It helps determine need for treatment with dexamethasone, nebulised adrenaline, inpatient care and admission to a paediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

- Mild (≤2): occasional barking cough, no stridor at rest, mild or no respiratory distress.

- Moderate (3-7): frequent barking cough, stridor at rest, no or little distress/agitation

- Severe (8-11): frequent barking cough, stridor at rest, significant distress/agitation

- Impending respiratory failure (≥12): reduced level of consciousness, stridor at rest, severe distress with/without cyanosis and poor air entry

Investigations

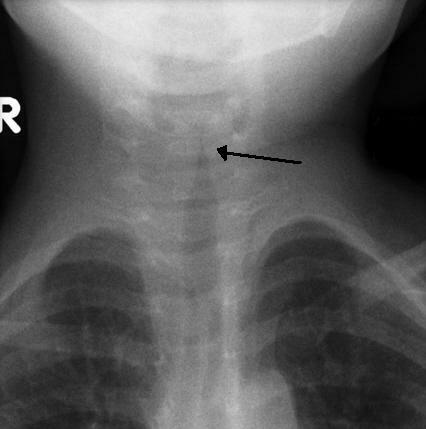

The characteristic sign of croup on plain film radiograph is the steeple sign.

Basic bedside observations are vital in any unwell child to determine the severity of illness. This includes regular assessment of respiratory rate, heart rate and oxygen saturations. Further investigations depend on the severity and the possibility of an alternative diagnosis.

Laboratory investigations

Rarely indicated in children with croup. Management is largely based on clinical assessment and subsequent treatment.

Most cases of croup are self-limiting, therefore, further investigations including viral culture is not necessary. However, if being admitted to hospital or when a firm aetiological diagnosis is required, confirmation by viral culture of secretions from the nasopharynx or throat can be completed. In hospital, this is typically needed for infection-control purposes.

Imaging

Imaging is not required for the diagnosis of croup. However, on plain film radiograph, the classical sign of croup is the ‘Steeple sign’. This refers to subglottic airway narrowing seen on x-ray due to inflammation and mucosal oedema.

Steeple sign on X-ray, arrow shows subglottic airway narrowing

Image courtesy of Dr Michael Sargent, Radiopaedia.org

Management

Management of croup is based on severity and centres on administration of dexamethasone.

The cornerstone of treatment in croup is dexamethasone, which can be given orally, intra-muscularly or intravenously. If all these routes are compromised, nebulised budesonide can be considered.

- All children: oral dexamethasone, single dose, check BNF or local guidelines for dose. Anti-pyretics, maintain hydration with oral fluids, avoid distress, regularly checking child, parent education.

- Mild (≤2): advice for all children, outpatient management.

- Moderate (3-7): advice for all children, consider outpatient management if improves with dexamethasone. If no improvement or ongoing respiratory distress, consider admission and nebulised adrenaline.

- Severe (8-11): advice for all children, nebulised adrenaline, usually require inpatient admission for observation. Repeat nebulised adrenaline as needed, consider PICU referral if worsening.

- Impending respiratory failure (≥12): advice for all children, nebulised adrenaline, urgent senior support including clinician with paediatric airway skills (e.g. Paediatric anaesthetist). PICU referral.

Complications

The majority of cases of croup are self-limiting with a full recovery.

Croup can lead to worsening respiratory failure with need for intubation, but this is only 1-3% of cases. The majority of patients have a self-limiting illness and even moderate to severe croup has an excellent prognosis following treatment with dexamethasone and nebulised adrenaline. Death from Croup occurs in < 1 in 30,000 cases.

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback