Agoraphobia

Notes

Introduction

Agoraphobia is derived from the Greek “agora” meaning a place of assembly or market-place and “phobia” meaning fear.

Agoraphobia is an anxiety disorder characterised by an excessive fear of situations where escape might be difficult or help might not be readily available. This can include situations such as using public transportation, being in crowds, and being out of the home alone. There is a fear that a panic attack or other incapacitating/embarrassing physical symptoms may occur in these situations. Individuals with agoraphobia therefore strive to avoid these situations or endure them with intense feelings of anxiety or fear. This fear is disproportionate to the actual danger posed by the situation. Agoraphobia results in severe impairment of an individual’s functioning and can occur alongside other mental health conditions such as depression and other anxiety disorders.

We will explore the features of agoraphobia in detail in the diagnosis section below. We have focussed on the diagnosis and treatment of agoraphobia in adults, however many of the same principles apply in children and adolescents.

Epidemiology

Agoraphobia is more commonly seen in women.

It is estimated that agoraphobia affects 1.7% of adults. It often begins in early adulthood, with the average age of onset being 17 years. Most cases of agoraphobia present before the age of 35 years. It is thought to be twice as common in females compared to males.

Aetiology & risk factors

The aetiology of agoraphobia, like most anxiety disorders, is based on a biopsychosocial model of the condition.

The aetiology of most anxiety disorders can be divided into environmental factors, genetic factors, and psychological traits of an individual.

Risk factors for the development of agoraphobia include:

- Female sex.

- Family history of agoraphobia or other anxiety disorder.

- Adverse childhood experiences (e.g. parental death, maltreatment, or abuse).

- Overprotection from primary caregivers in childhood.

- Experiencing a stressful event (e.g. bereavement, being attacked).

- Other mental health disorders (e.g. other anxiety disorders and depression).

- Comorbid physical condition (e.g. epilepsy).

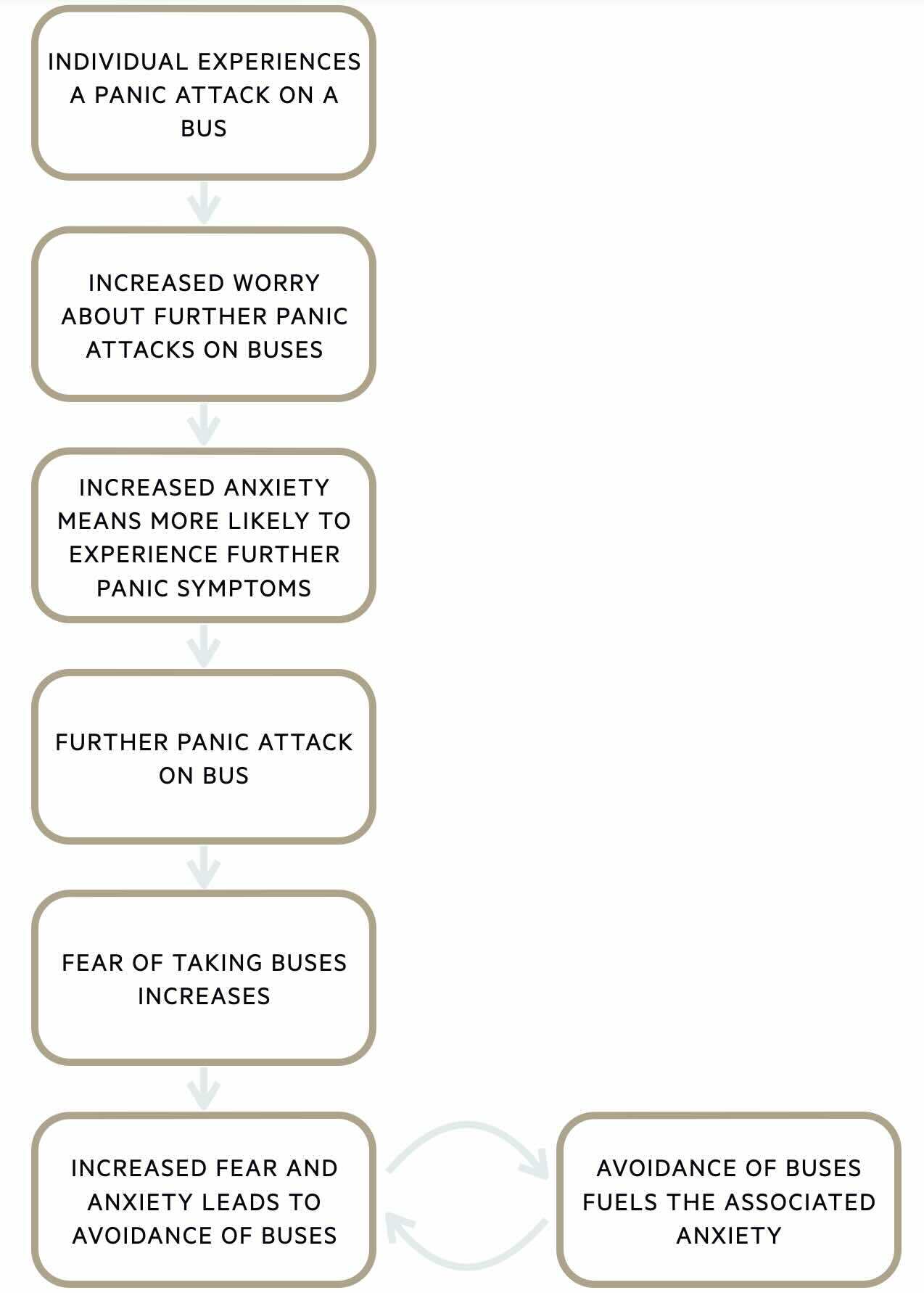

Agoraphobia may develop following an individual experiencing a panic attack or other embarrassing/incapacitating symptoms in a specific situation. The individual may worry so much about having another panic attack, that they feel panic-like symptoms returning when they are in a similar situation. This results in the individual avoiding that specific situation as a means to control their anxiety. This is exampled further in the following illustration:

Clinical features & diagnosis

Agoraphobia is characterised by a marked fear or anxiety about specific situations, wherein the presence of panic-like or incapacitating symptoms, provokes thoughts of being difficult to escape or where help might not be available.

Both DSM-V and ICD-11 can be used as frameworks to aid the clinical diagnosis of agoraphobia. Below the diagnosis of agoraphobia is outlined using DSM-V criteria:

Marked fear or anxiety about two or more of the following 5 situations:

- Using public transportation (e.g. buses, trains, planes).

- Being in open spaces (e.g. bridges, parking lots).

- Being in enclosed spaces (e.g. shops, cinema, theatre).

- Standing in line or being in a crowd.

- Being outside of the home alone.

The individual fears these situations because, in the event of developing panic-like symptoms or other embarrassing or incapacitating symptoms (e.g. falls, incontinence), they have thoughts that:

- Escape might be difficult, OR

- Help might not be available

The fear or anxiety is:

- Almost always provoked by the situations.

- Disproportionate to the actual danger posed by the situation.

This leads to the following situations being:

- Actively avoided, OR

- Requiring the presence of a companion, OR

- Endured with intense fear or anxiety.

The fear, anxiety, or avoidance behaviours are described as being persistent (i.e. lasting for > 6 months) and causing the affected individual significant distress or functional impairment (i.e. social, occupational, or other important aspects of functioning). If a medical condition is present that makes embarrassing or incapacitating symptoms more likely to occur (e.g. incontinence in inflammatory bowel disease, or falls in Parkinson’s disease), the fear/anxiety/avoidance is clearly excessive.

Differential diagnosis

In agoraphobia, panic attacks tend to be predictable and occur in the context of the avoided situation that differs from panic disorder.

- Generalised anxiety disorder: excessive anxiety about many events and activities, not limited to the situations and anxieties that characterise agoraphobia.

- Social anxiety disorder: anxiety is confined to social situations and the fear is of being negatively judged by others, rather than fear of being unable to escape/get help as in agoraphobia.

- Specific phobia: may be diagnosed if fear, anxiety and avoidance behaviour is limited to one of the five situations in which agoraphobia can occur. A diagnosis of agoraphobia requires at least two of five situations.

- Separation anxiety disorder: fear and anxiety caused by anticipation of separation from loved ones or the home environment, rather than the panic being associated with the feared situations.

- Panic disorder: if panic attacks occur in the context of agoraphobia they tend to be predictable and occur in the above situations. In panic disorder, panic attacks are unexpected with no clear trigger.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): disproportionate anxiety and avoidance behaviours can be seen in OCD, for example, obsessions about contamination may drive compulsive behaviour to avoid certain situations deemed to be high risk for contamination.

- Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD): in BDD the individual may also avoid leaving the house, but this anxiety and avoidance behaviour is driven by perceived flaws in physical appearance.

- Post-traumatic stress disorder: anxiety and avoidance behaviours are key features in both agoraphobia and PTSD.

Management

Agoraphobia can be treated with talking therapies, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of these treatments.

Agoraphobia can be treated with talking therapies, medication, or a combination of the two. Decisions around treatment will be guided by the severity of the presentation and patient preference. For those with agoraphobia that only results in mild to moderate functional impairment, psychotherapy is usually the first-line option. For agoraphobia that has a more severe impact on an individual’s functioning, they are likely to benefit from a combination of psychotherapy and medication.

- Mild-to-moderate functional impairment: Low-intensity psychological intervention (e.g. guided self-help, psychoeducational groups)

- Severe functional impairment: Pharmacotherapy (e.g. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor first-line) AND high-intensity psychological intervention (e.g. applied relaxation, cognitive behavioural therapy)

Psychological therapies

The two high-intensity psychological therapies are cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and applied relaxation:

- Cognitive behavioural therapy: Aims to focus on the link between thoughts, behaviours, and emotions. Challenges negative thoughts and changing unhelpful behaviours can have a positive impact on how a person feels. Individual CBT for agoraphobia usually consists of 12-15 weekly hour-long sessions.

- Applied relaxation: Aims to identify signs of tension. Then the therapist can teach individuals exercises to relax muscles and relieve tension. Relaxation techniques are usually practised in low-stress environments, before being used in more stressful situations to prevent and manage anxiety/panic. Applied relaxation for agoraphobia usually consists of 12-15 weekly hour-long sessions.

In CBT, the behavioural component involves exposure therapy. This means the individual is supported to gradually expose themselves to the situations that are feared and usually avoided. This process is called systematic desensitisation which is a commonly used method for the treatment of phobias. It involves working with a therapist to construct an anxiety “hierarchy” that ranks situations that cause the least anxiety to the most anxiety. The individual is supported by the therapist to gradually work their way up the anxiety hierarchy, and expose themselves to these situations. The therapist also teaches the individual relaxation techniques to help manage anxiety at each stage of the hierarchy. The aim is to reduce the fear response and replace this with a relaxation response.

Pharmacological therapies

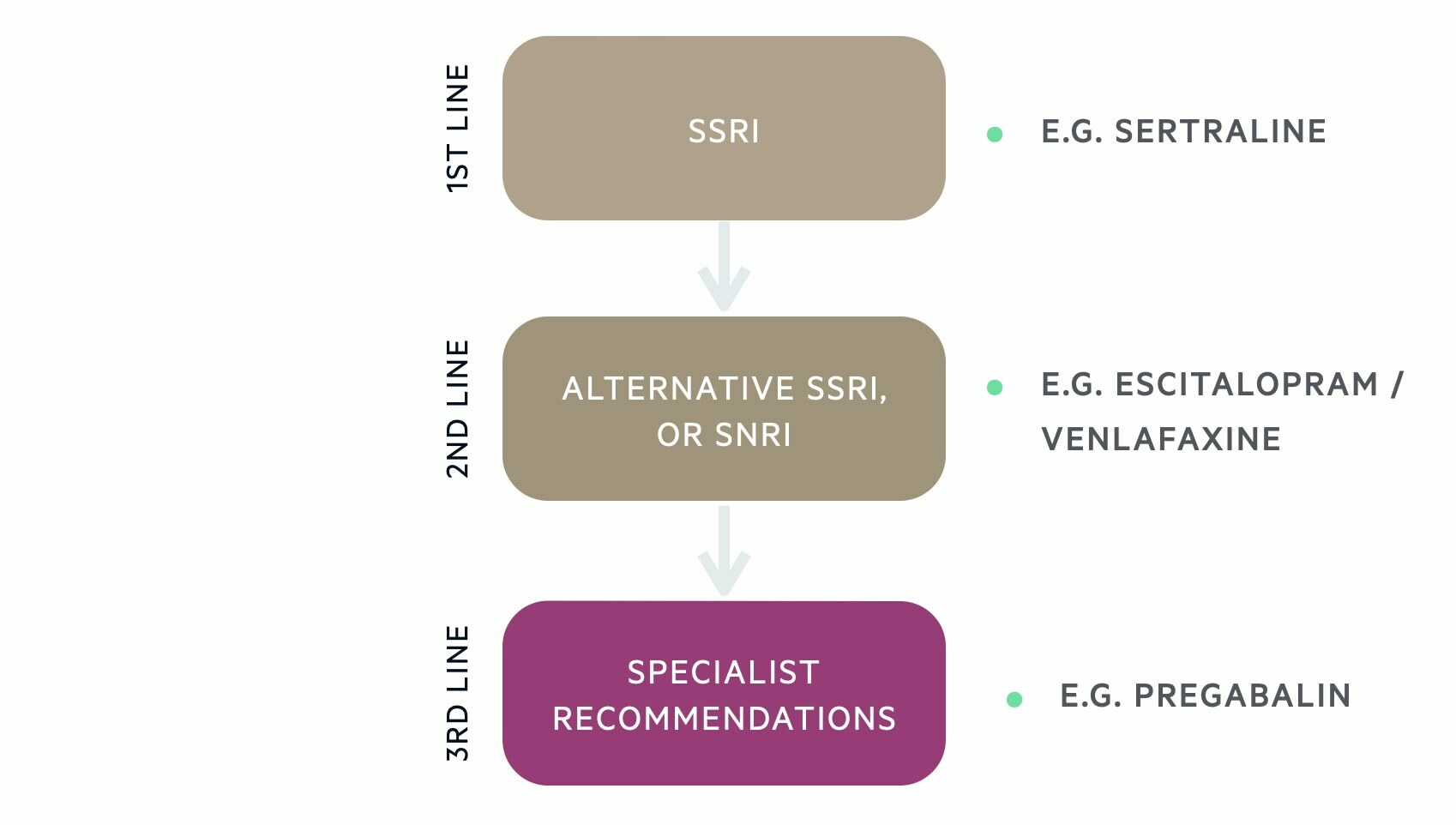

The principal drug class for the treatment of agoraphobia are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). An SSRI at maximally tolerated dose should be tried for a minimum of six weeks. If there is a poor or inadequate response then second-line treatment is usually a second SSRI. Poor response to one SSRI does not predict the failure of another. An alternative second-line therapy is a serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI; e.g. venlafaxine). After this, the evidence for drug therapy is not as conclusive and should be guided and/or initiated by a psychiatrist.

Before starting an SSRI or SNRI, it is important to:

- Explain the likely benefits.

- Advise patients when they might start experiencing anxiolytic effects (2 weeks) and the likely treatment duration (at least 6 months).

- Inform about possible side effects (including a transient increase in anxiety).

- Advise patients not to cease medication abruptly due to the risk of discontinuation syndrome and relapse in symptoms.

NOTE: Major side-effects of SSRIs and SNRIs include: GI disturbance (loss of appetite, nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, constipation), headaches, poor sleep, transient increase in anxiety, palpitations, sexual dysfunction (loss of libido, erectile dysfunction, inability to orgasm).

For individuals who are < 30 years old, it is important to:

- Warn them that SSRIs and SNRIs are thought to be associated with an increased risk of suicidal thinking and self-harm in younger patients.

- Review within one week of prescribing an SSRI/SNRI.

- Continue to monitor the risk of suicide and self-harm every week for the first month.

When monitoring for a clinical response to an SSRI or SNRI, it is important to remember that a therapeutic response will take two or more weeks for an anxiolytic effect. Patients should be advised to remain on an SSRI for at leats six months after the remission of symptoms and that there is a high chance of relapse if medication is stopped abruptly.

For those with anxiety disorders, DO NOT routinely offer benzodiazepines except as a short-term measure during a crisis.

Other management considerations

As with other mental health disorders, the following points also form an important part of any management plan and should be considered:

- Explain and educate: written information on agoraphobia and treatment options is often helpful, as it may be hard for the patient to retain information given verbally. It can also be helpful to give lifestyle advice that can help manage anxiety including exercising regularly, eating a healthy diet, avoiding caffeinated drinks, and avoiding alcohol consumption.

- Involve the support network: family may benefit from practical or emotional support and education about agoraphobia.

- Assess and manage risk: those deemed to be high risk to themselves may require more intensive support and monitoring (e.g. home treatment team, inpatient admission).

- Active monitoring: the management plan may need to change if the individual’s presentation or risks change.

- Screen for co-morbidities: assess for and provide appropriate treatment for commonly co-occurring mental health disorders including other anxiety disorders, depression, and substance or alcohol misuse.

- Assess their physical health: especially if agoraphobia means they have been unable to attend GP/hospital appointments.

- Assess their social needs.

Last updated: December 2023

References:

DSM-V

ICD-11

NHS website: Treatment - Agoraphobia

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback