Alcohol misuse, dependence, and withdrawal

Notes

Introduction

Alcohol dependence develops after a period of regular alcohol consumption and is characterised by craving, tolerance, loss of control, withdrawal symptoms, and persistent use despite negative harm.

Alcohol is a psychoactive substance that has been widely used in different cultures for centuries. Excessive and harmful use of alcohol can have negative individual consequences (e.g. physical, psychological, economic, and social). There are also wider harmful consequences to society at large.

Alcohol intoxication is typically referred to as being “drunk” or inebriated. Desirable effects of alcohol intoxication include relaxation, euphoria, and social disinhibition. Other effects range from mild (e.g. impairments in balance, coordination, speech, memory, attention, and sleepiness) to more severe (e.g. vomiting, amnesia, loss of consciousness, respiratory depression).

Alcohol dependence develops after a period of regular alcohol consumption. The key elements of alcohol dependence include:

- Craving: a strong desire or compulsion to drink alcohol.

- Loss of control: over the consumption of alcohol.

- Tolerance: needing increasing amounts of alcohol to produce the desired effect.

- Withdrawal symptoms: when alcohol use is ceased or reduced.

- Abnormal priorities: alcohol use takes priority and other important activities/interests are neglected.

- Harm: persistent alcohol use despite harmful consequences.

We advise that before reading these notes, you familiarise yourself with the notes on general principles of substance use disorders. The following notes detail basic principles about units of alcohol, the pharmacology of alcohol, screening tools used for problem-drinking, how to diagnose alcohol use disorder, management of alcohol withdrawal, and additional treatment considerations in this population including relapse prevention.

Alcohol units and guidelines

One unit of alcohol is equivalent to 10 ml or 8 g of pure alcohol.

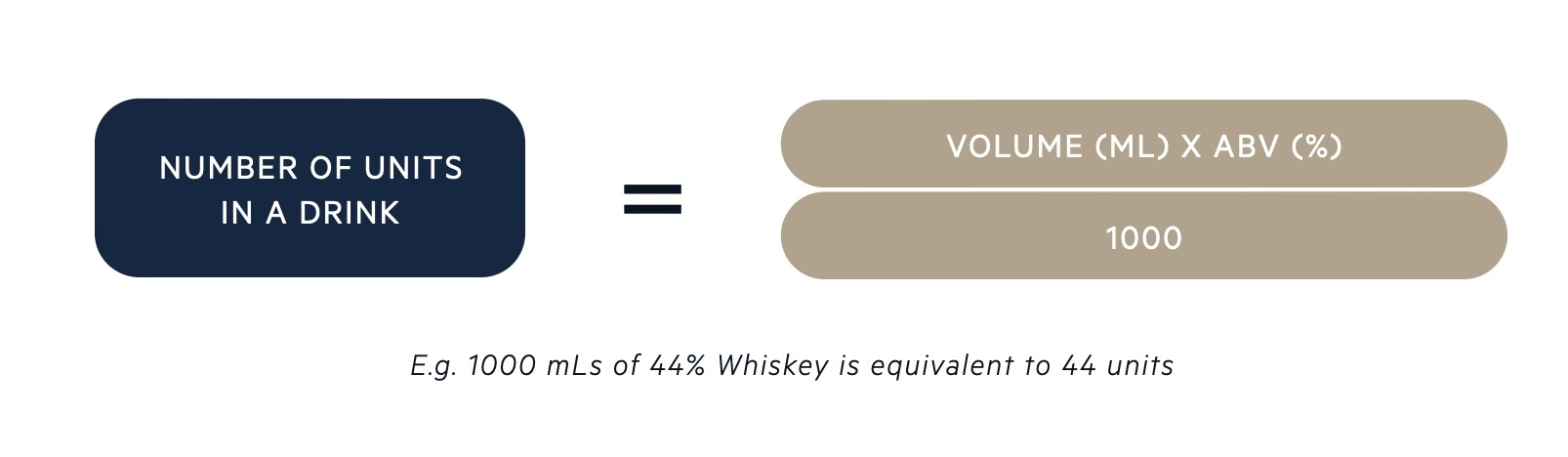

The idea of counting alcohol units was first introduced in 1987 to help people keep track of their drinking. Alcohol units are a way of expressing the quantity of pure alcohol in a drink:

"1 unit of alcohol = 8 g of pure alcohol"

The number of units in a drink will depend on the size and strength of the drink.

Alcohol By Volume (ABV) is a measure of the strength of a drink. ABV is the amount of pure alcohol as a percentage (%) of the total volume of liquid in a drink. For example, a wine that has 12% ABV means that 12% of the volume of the drink is pure alcohol. ABV and the number of units of alcohol (e.g. in a bottle, can, or typical serving) is indicated on the drink container. The number of units in an alcoholic drink can be calculated from the following equation:

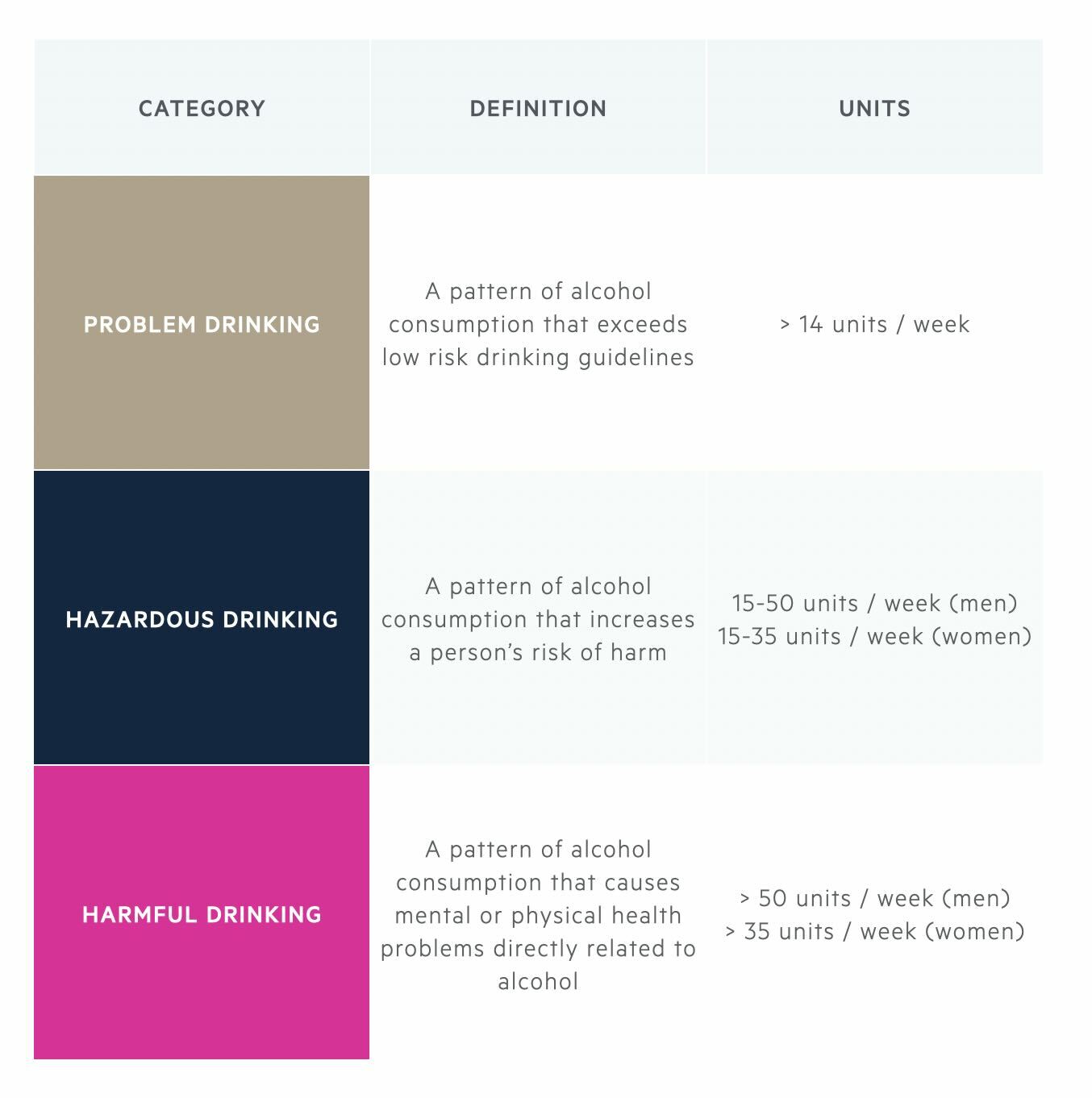

UK government guidelines advise that men and women should drink no more than 14 units of alcohol per week on a regular basis. The table below describes the terms used by the NICE guidelines for abnormal consumption of alcohol, which is broadly based on the number of units consumed per week.

Alcohol pharmacology

Alcohol increases Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) function through the activation of GABA-A receptors.

GABA is a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain that produces a calming effect. The effect of alcohol on GABA is responsible for its relaxing, sedating, and anxiolytic effects.

Alcohol reduces glutamate function through inhibitory action at NMDA glutamate receptors. Glutamate is a major excitatory neurotransmitter that is involved in brain processes such as learning and memory. The effect of alcohol on glutamate is responsible for effects such as amnesia and sedation.

Chronic alcohol consumption leads to the development of tolerance, as receptors in the brain gradually adapt to and compensate for the effects of alcohol. The key neurotransmitters involved in tolerance are GABA and glutamate. Chronic alcohol intake leads to reduced GABA activity (downregulation in GABA-A receptors) and increased glutamate activity (increased expression of NMDA receptors).

This imbalance in GABA and glutamate is manageable in the presence of alcohol, as it counterbalances by increasing GABA activity and reducing glutamate activity. However, when alcohol consumption is ceased, the reduced GABA activity and increased glutamate activity result in brain over-stimulation and features of alcohol withdrawal.

Epidemiology

The excess consumption of alcohol is a significant problem in the United Kingdom.

Among the adult population in England, it is estimated that 21% regularly drink at levels that increase their risk of ill health. Studies suggest that there is a higher prevalence of hazardous and harmful drinking in men compared to women (2:1). Alcohol use disorder has a lifetime prevalence of 7-10% in most Western Countries.

Aetiology and risk factors

The development of alcohol dependence is multifactorial.

Multiple factors are thought to contribute to the increased risk of developing alcohol use disorders.

Risk factors include:

- Family history: alcohol dependence has been found to run in families. Offspring of parents with alcohol dependence are four times more likely to develop the disorder.

- Social influences: individuals may learn from families or peer groups who model patterns of drinking. Behaviour may also be influenced by social expectations or pressure to drink.

- Environmental influences: include alcohol being easily available, affordable, and the normalisation of drinking culture.

- Personality traits: including disinhibition, poor impulse control, novelty, or sensation seeking may increase the risk of problem drinking.

- Psychiatric co-morbidities (e.g. depression, anxiety, PTSD, psychosis): the pleasurable effects of alcohol can temporarily reduce the symptoms of anxiety/depression, and alcohol may be used in an attempt to self-medicate these symptoms.

- Genetics: evidence supports the influence of specific genes on an individual’s susceptibility to developing alcohol use disorders (both protective genes and those that pose an increased risk).

- Adverse life events: these may trigger excessive drinking (e.g. abuse, bereavement, job loss)

Clinical features & diagnosis

The diagnosis of alcohol use disorder depends on the presence of a collection of features similar to any addiction or dependency.

Below is a list of clinical features typical of alcohol misuse and dependency that are used as part of the DSM-V criteria for the diagnosis of Alcohol Use Disorder.

Alcohol Use Disorder is defined as a problematic pattern of alcohol use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress.

At least two of the following features that occur within a 12-month period are used to form the diagnosis:

- Increased consumption: alcohol is often taken in larger amounts or over longer periods than intended.

- Loss of control: persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use.

- Time-consuming: a lot of time spent in activities necessary to obtain alcohol, drink alcohol, or recover from its effects.

- Craving: a strong desire or urge for alcohol.

- Not fulfilling responsibilities: recurrent alcohol use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home.

- Continued alcohol use despite negative effects on social or interpersonal problems: these problems are likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the effects of alcohol.

- Drinking takes priority over other activities: important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of alcohol use.

- Recurrent alcohol misuse in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Continued alcohol use despite negative effects of alcohol on physical or mental health.

- Tolerance: a need for increased alcohol to achieve intoxication or diminished effects with continued use of the same amount of alcohol.

- Withdrawal: symptoms upon ceasing drinking, or avoiding the effects of withdrawal by continuing to drink alcohol.

Screening tools for problem drinking

A number brief screening tools can be used to assess patients for problem-drinking.

CAGE Questionnaire is a well-known screening test for problem drinking and is comprised of 4 questions:

1. Have you ever felt you should Cut down on your drinking?

2. Have people Annoyed you by criticising your drinking?

3. Have you ever felt bad or Guilty about your drinking?

4. Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or to get rid of a hangover (Eye opener)?

Answering yes to ≥ 2 of the CAGE questions is considered clinically significant (sensitivity 93% and specificity 76% for identification of problem drinking).

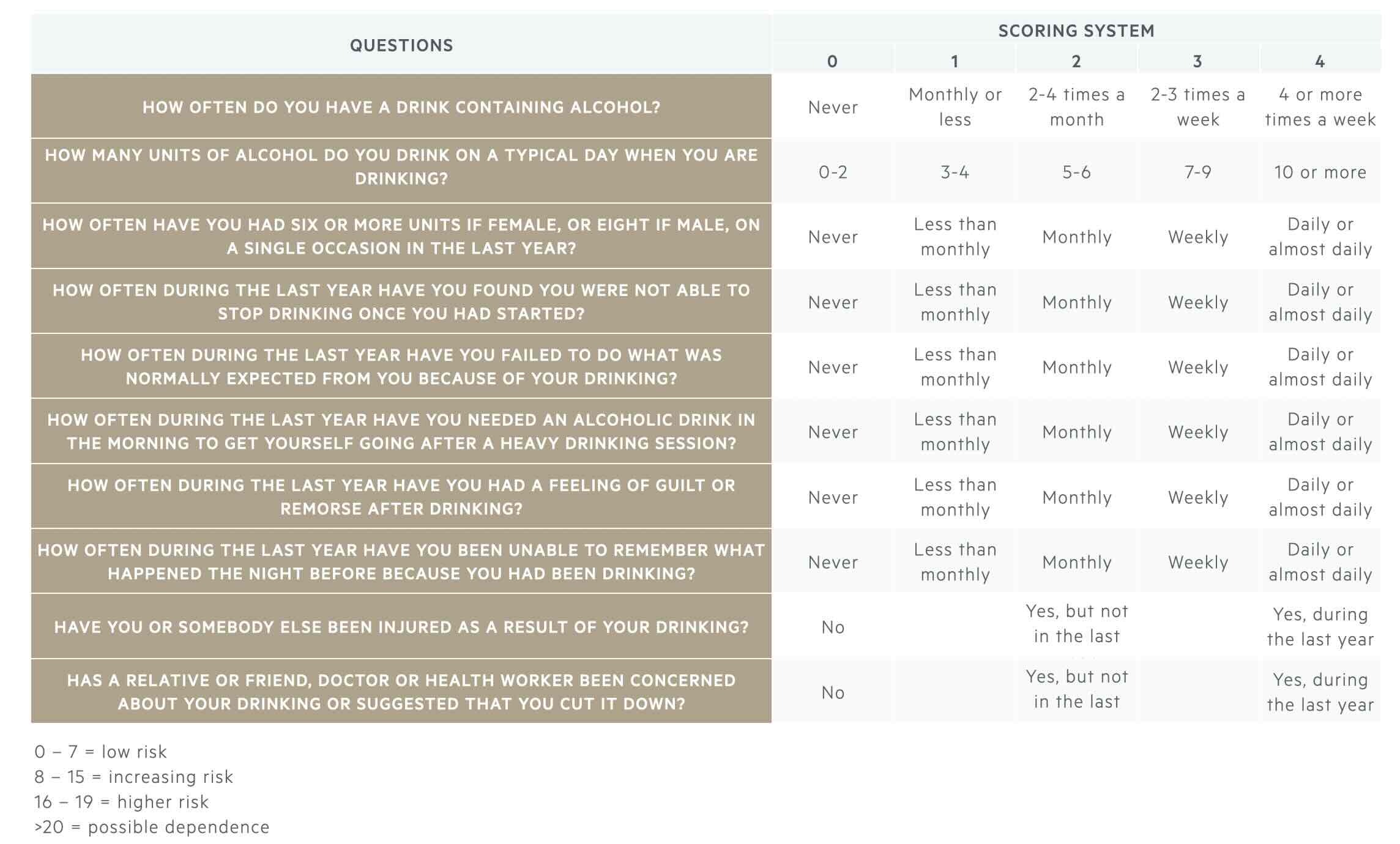

The AUDIT questionnaire (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) is a longer screening tool that is recommended by the World Health Organisation and used to assess the pattern and severity of alcohol misuse:

Once alcohol dependency has been identified, the Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire (SADQ) can be used to assess the severity of alcohol dependence. This is a self-administered 20-item questionnaire designed by WHO.

Management

The management of alcohol dependence and misuse can be complex and depends on the presentation (e.g. withdrawal, intoxication, chronic use).

The management of problem drinking can be divided into:

- Management of alcohol intoxication

- Assessment and management of alcohol withdrawal

- Thiamine supplementation

- Pharmacological treatment for relapse prevention

- Psychological and social support

- Management of co-morbid mental and physical health issues

For a detailed discussion on each of these areas, see the topic subsections below.

Alcohol intoxication

Alcohol intoxication is a very common occurrence within the United Kingdom.

The symptoms of alcohol intoxication range from mild to severe and depend on how much alcohol a person has consumed and how quickly their body can metabolise it. The features can include the following:

- Mild symptoms: impairments in speech, memory, balance, coordination, attention, and sleepiness.

- Severe symptoms: vomiting, amnesia, loss of consciousness, respiratory depression, and risk of death.

There are no specific NICE Guidelines for the management of alcohol intoxication. In clinical practice, management is largely supportive whilst waiting for the individual to metabolise the alcohol. The individual is closely monitored to ensure that they are maintaining their airway and that vital signs are within normal limits. They are often placed in the recovery position to reduce to risk of aspirating vomit. Oxygen and intravenous fluids may also be given as supportive measures.

Alcohol intoxication may be confirmed with a breathalyser if one is available. It is important to consider and investigate other medical issues that can present similarly to alcohol intoxication including overdose of other sedative agents (e.g. opioids, benzodiazepines), hypoglycaemia, head injury, cerebrovascular accident (haemorrhage or infarction), post-ictal state, and sepsis.

After supportive management of acute alcohol intoxication, clinical attention turns to managing alcohol withdrawal features and thiamine supplementation (see below).

Alcohol withdrawal

Alcohol withdrawal occurs in patients who are alcohol-dependent and have stopped or significantly reduced their alcohol intake.

People who are alcohol-dependent are advised not to suddenly reduce their alcohol intake. This is because suddenly stopping or significantly reducing their alcohol consumption can increase their risk of alcohol withdrawal including the risk of seizure.

Chronic alcohol consumption leads to the development of tolerance as receptors in the brain gradually adapt to, and compensate for, the effects of alcohol (chronic alcohol intake leads to reduced GABA activity and increased glutamate activity). When alcohol consumption is ceased, the imbalance between GABA and glutamate results in brain over-stimulation. This reduction in GABA activity and excess glutamate activity manifests in alcohol withdrawal symptoms detailed below:

- Psychological: agitation, anxiety, irritability, insomnia.

- Neurological: headache, tremor, disorientation (time, place, and person), seizures.

- Gastrointestinal: nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea.

- Cardiovascular: tachycardia, hypertension.

- Metabolic: sweats, fever.

- Visual disturbance: hypersensitive to light, visual hallucinations.

- Auditory disturbance: hypersensitive to sounds, auditory hallucinations.

- Tactile disturbance: itching, pins and needles, crawling bug sensation.

Timing of alcohol withdrawal

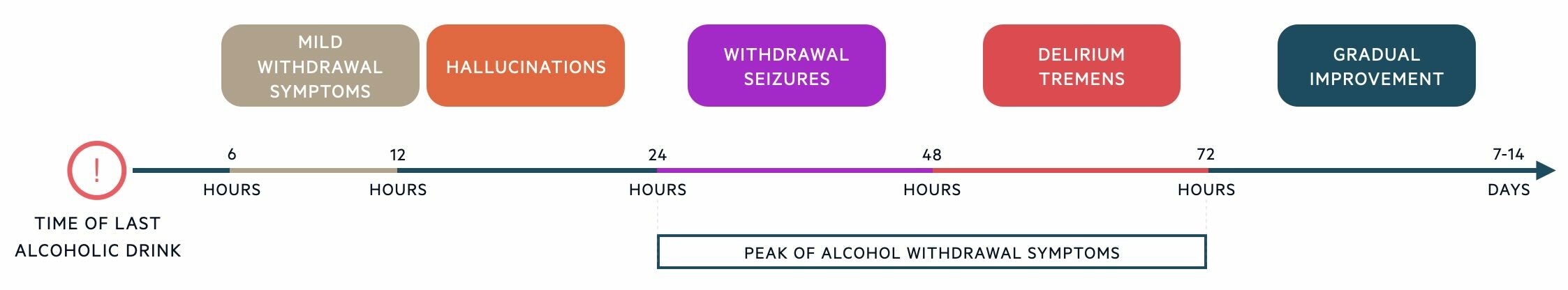

The timing of alcohol withdrawal is very typical with early features of tremors, headache, and sweating, which are later followed by features of hallucinations and seizures when symptoms are at their peak around 24-72 hours. Delirium Tremens (DT) is the most severe form of alcohol withdrawal that is considered a medical emergency and can be life-threatening.

Typical alcohol withdrawal timeline (after the individual's last drink):

- 6-12 hours: an individual may experience the onset of minor withdrawal symptoms including tremor, headache, sweating, anxiety, and nausea.

- 12-24 hours: the individual may start to experience auditory, tactile, or visual hallucinations.

- 24-48 hours: the risk of alcohol withdrawal seizures is highest. These are usually generalised tonic-clonic seizures and occur in 1-3% of alcohol withdrawal cases.

- 48-72 hours: Delirium Tremens may manifest.

- 5-14 days: Alcohol withdrawal symptoms have often resolved within 5 days but can last up to 14 days.

Delirium Tremens

DT is a medical emergency that occurs in 2% of alcohol withdrawal cases and has a mortality rate of 37%. It is the most severe form of alcohol withdrawal that is characterised by confusion, autonomic hyperactivity, and cardiovascular collapse (e.g. haemodynamic instability). The clinical features of DT include the rapid onset of the following:

- Delirium/profound confusion: often worse at night, disorientated to time and place, clouding of consciousness, impairment of recent memory, agitation.

- Hallucinations: particularly visual and tactile hallucinations.

- Coarse tremor

- Sympathetic overactivity: sweating, fever, tachycardia, hypertension.

Patients with DT may present with profound electrolyte distrubance and hypovolaemia. It is essential to monitor electrolytes closely and profound aggressively fluid resuscitation in addition to management of withdrawal symptoms.

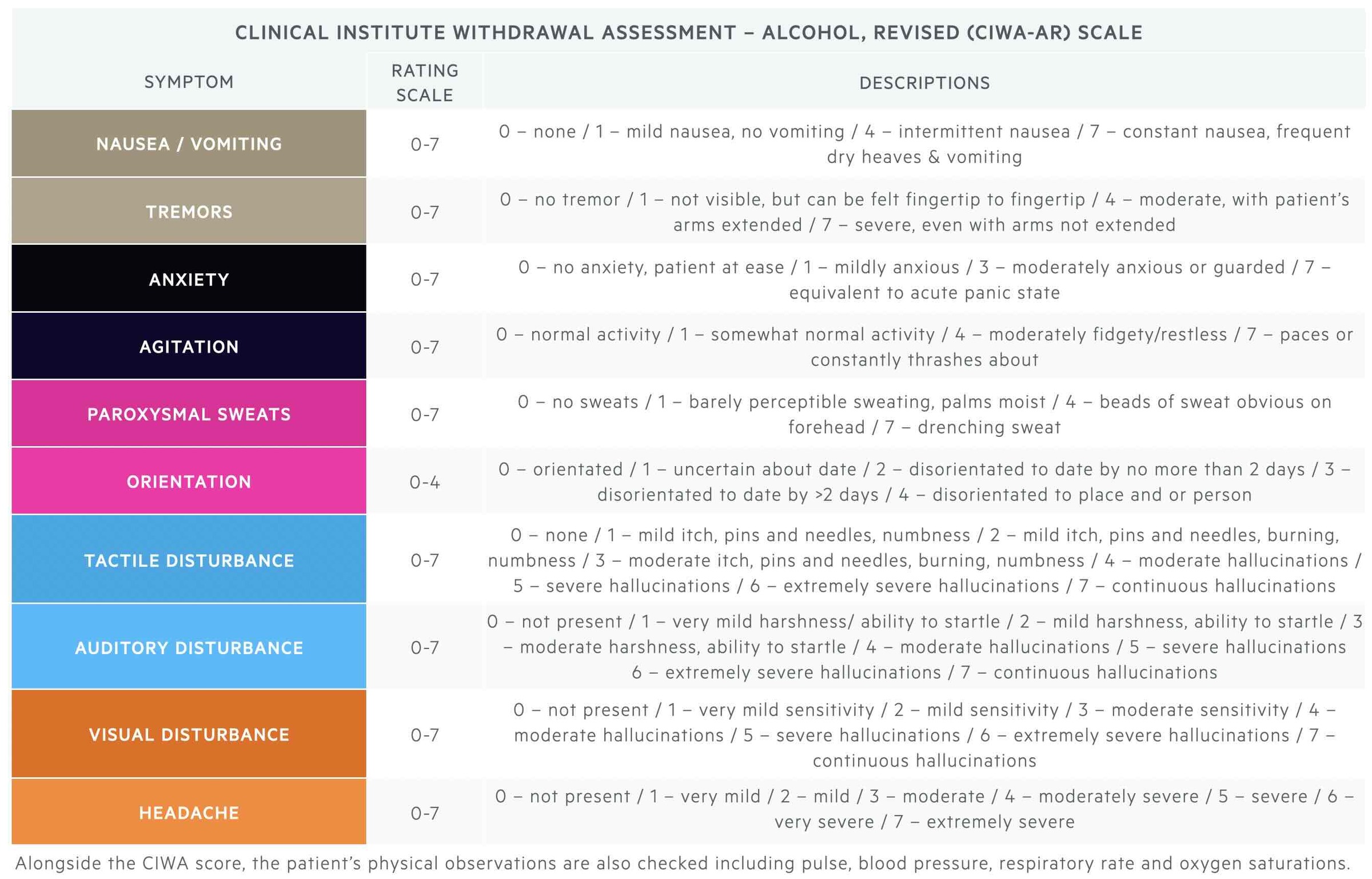

CIWA-Ar scale

The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment – Alcohol, revised (CIWA-Ar) scale is a validated 10-item assessment tool that is used to quantify the severity of alcohol withdrawal symptoms, to guide treatment, and to monitor response. The CIWA-Ar is used to guide the pharmacological management of alcohol withdrawal.

Clinicians add up scores for all ten criteria. The total CIWA score can be used to assess the presence and severity of alcohol withdrawal:

- Absent or minimal withdrawal: score 0-9

- Moderate withdrawal: score 10-19

- Severe withdrawal: score > 20

The total CIWA score influences the frequency at which further observations are made:

- Initial score is ≥ 8: repeat hourly for 8 hours. Then if stable 2-hourly for 8 hours. Then if stable 4-hourly.

- Initial score < 8: assess 4-hourly for 72 hours and if score < 8 for 72 hours, discontinue assessment.

The total CIWA score guides clinicians with regards to the need for pharmacological management of alcohol withdrawal:

- Symptom-triggered regimen (not prescribed regular withdrawal medication): give PRN medication when CIWA score is ≥ 8

- Fixed-dose reducing regime with PRN medication (prescribed regular withdrawal medication): give additional PRN medication if CIWA score is ≥ 15

Pharmacological management of alcohol withdrawal and detoxification

Benzodiazepines are the treatment of choice for alcohol withdrawal. Benzodiazepines are similar to alcohol in that they enhance the effect of GABA at GABA-A receptors. They are also used for their anticonvulsant properties.

Chlordiazepoxide is the benzodiazepine most often used in the UK. This is a long-acting benzodiazepine with a relatively low dependence-forming potential. Short-acting benzodiazepines are preferred in those with impaired liver function. The following benzodiazepines may be used for the management of alcohol withdrawal:

- Chlordiazepoxide: Long-acting, half-life 24-100 hours.

- Diazepam: Long-acting, half-life 20-100 hours.

- Lorazepam: Short-acting, half-life 10-20 hours.

- Oxazepam: Short-acting, half-life 3-21 hours.

Benzodiazepines can be prescribed as a symptom-triggered regimen or a fixed-dose reducing regime.

- Symptom-triggered regimen: clinicians monitor the patient for signs of alcohol withdrawal and give benzodiazepine as required (i.e. PRN).

- Fixed-dose reducing regime: the initial dose of benzodiazepine is determined by their level of alcohol consumption and the severity of alcohol dependence. The starting dose of chlordiazepoxide required can be estimated from the current alcohol consumption (e.g. if alcohol consumption is 20 units a day, the starting dose might be 20 mg QDS). The dose is then gradually reduced and stopped over 5-10 days. The rate of dose reduction may need to be altered, depending on the CIWA-Ar score and whether the individual is requiring additional PRN chlordiazepoxide.

The more severe manifestations of alcohol withdrawal including alcohol withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens are also managed with benzodiazepines.

Community versus inpatient alcohol detoxification

NICE Guidelines advise that for people in acute alcohol withdrawal, or who are assessed to be at high-risk of developing alcohol withdrawal seizures or delirium tremens, they should be offered admission to hospital for medically assisted alcohol withdrawal as an inpatient. Inpatient-assisted withdrawal may also be considered if the individual drinks >30 units of alcohol a day or if they have a history of epilepsy or previous alcohol withdrawal seizures.

Community detoxification may be appropriate if the individual is motivated to stop drinking. They must have consistent support (e.g. family member, social worker, or carer) who can support them attending daily outpatient appointments to undergo clinical review and obtain medications. No more than two days supply of medication should be given at any time to prevent the risk of overdose or diversion. Outpatient-based community-assisted withdrawal programmes should also consist of psychosocial support alongside the drug regimen. Community detoxification programmes should be stopped if the patient resumes drinking or fails to engage with the treatment plan.

Thiamine supplementation

Patients with alcohol dependency are at risk of the neuropsychiatric condition Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome because of thiamine deficiency.

In alcohol dependence, patients commonly develop thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency due to a variety of mechanisms (e.g. poor diet, reduced absorption, impaired utilisation, reduced hepatic uptake). This makes patients are high-risk of developing Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome (WKS), which refers to a disease spectrum causing two classical neurological syndromes:

- Wernicke's encephalopathy (WE): an acute encephalopathy characterised by a triad of confusion, ataxia, and oculomotor dysfunction.

- Korsakoff syndrome (KS): a chronic amnesic syndrome characterised by defects in both anterograde and retrograde memory.

KS is essentially the late neuropsychiatric manifestation of WE if it goes unnoticed or untreated. Once KS has been established, patients rarely recover. This means early recognition and treatment of WE with high-dose B vitamins (e.g. Pabrinex®) is critical to prevent permanent neurological damage. Importantly, thiamine is required to utilise glucose. Therefore, a glucose load in a thiamine-deficient patient can precipitate WE and patients must be treated with high-dose B vitamins before administration of glucose.

For more information, see our note on Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.

Pharmacological treatment for relapse prevention

Pharmacological agents including Acamprosate, Naltrexone, and Disulfiram can all be used to prevent relapse of alcohol consumption.

After successful assisted withdrawal in those with alcohol dependence, psychological intervention, and pharmacological treatment can significantly aid relapse prevention. The three main drugs used to prevent relapse to alcohol misuse include Acamprosate, Naltrexone, and Disulfiram.

Acamprosate

Acamprosate is a glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist, which increases GABA functioning. This is thought to help restore the balance between neuronal excitation and inhibition (i.e. the balance of GABA/glutamate activity).

Acamprosate reduces alcohol cravings and should be started as soon as possible after abstinence or assisted detox is achieved. Acamprosate should be stopped if drinking persists 4-6 weeks after starting the drug. It is usually prescribed for up to 6 months (with monthly reviews), or longer for those benefiting from the drug and wish to continue.

Naltrexone / Nalmefene

Both drugs are opioid receptor antagonists that prevent increased dopamine activity after alcohol consumption. This means the rewarding effects of alcohol are reduced.

Naltrexone and Nalmefene reduce alcohol cravings, and if the individual does drink, the pleasurable effects of alcohol are reduced. These have been shown to significantly reduce relapse to heavy drinking. They should be started as soon as possible after abstinence or assisted detox is achieved. They should be stopped if drinking persists 4-6 weeks after starting the drug. They are usually prescribed for up to 6 months (with monthly reviews), or longer for those benefiting from the drug and wish to continue.

Disulfiram

Disulfiram inhibits the enzyme acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. This enzyme has an important role in the metabolism of ethanol in the liver by converting it to acetaldehyde. The same enzyme then converts acetaldehyde into acetate.

The inhibition of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase prevents the complete metabolism of alcohol. This causes an accumulation of acetaldehyde (the toxic-intermediate product). This results in an unpleasant alcohol-disulfiram reaction that is characterised by facial flushing, sweating, nausea, dizziness, headache, and palpitations. This is similar to the reaction alcohol has on certain Asian populations due to reduced activity or deficiency of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase.

Disulfiram works to reduce cravings and consumption due to the mental anticipation of this unpleasant reaction, rather than the adverse reaction itself. It can be used if acamprosate and naltrexone are unsuitable and should be started at least 24 hours after the last drink of alcohol. Regular clinical reviews are important.

Psychological and social support

Several psychological and social therapies can help people with alcohol use disorder or harmful drinking.

Psychological support that can be offered to patients include:

- Motivational interviewing

- Psychological interventions (e.g. CBT, Behavioural therapy, social network and environment therapies)

- Community support networks or self-help groups (e.g., Alcoholics Anonymous, SMART Recovery)

- Support from family and/or carers

- Referral to Community Drug and Alcohol Services: provides a more comprehensive assessment of their needs and more specialised community support.

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) is when the clinician adopts a supportive collaborative approach to the client, that aims to strengthen the individual’s motivation and commitment to change. MI allows the individual to identify their reasons for change based on their values and interests. NICE Guidelines advise that clinicians incorporate key MI principles into their reviews of those with alcohol use disorder.

In primary care, structured brief advice about alcohol consumption should be offered. An extended brief intervention (of up to 5 sessions) may be offered to those who require additional input. This intervention might focus on:

- Helping the individual recognise problems related to their drinking.

- Encouraging the individual to consider reasons for changing behaviour (including potential benefits to health and wellbeing) and helping resolve ambivalence to change.

- Addressing barriers to change, encouraging positive change, and belief in the ability to change.

- Outlining practical strategies to help reduce alcohol consumption (e.g. avoiding high-risk situations for drinking, recognising personal cues for drinking, alternating between alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks, switching to lower-strength beverages).

- Goal setting for the individual: this might be complete abstinence from alcohol or reduction of drinking.

Psychological interventions

Psychological interventions advised for alcohol dependence, focus specifically on alcohol-related cognitions, behaviours, problems and social networks.

NICE Guidelines support the use of the following psychological therapies:

- Cognitive behavioural therapy: focuses on identifying and modifying unhelpful thoughts about drinking and changing unhelpful behaviours that perpetuate alcohol misuse.

- Behavioural therapy: focuses on changing unhelpful behaviours that perpetuate alcohol misuse.

- Social network and environment-based therapies: focuses on adapting the individual’s environment and social network, to help achieve abstinence or controlled drinking. The individual is supported to build social networks supportive of change and take part in recreational activities that do not promote alcohol use.

- Behavioural couples therapy: focuses on alcohol-related problems and their impact on relationships.

Risk assessment should always form an important part of any management plan. Those who misuse alcohol may be at higher risk of deliberate self-harm, accidental self-harm, and suicide. They may also be more vulnerable to the risk of harm from others and at risk of causing harm to others (including indirect harm to children they are responsible for).

Management of co-morbidites

Anxiety and depression are common psychiatric co-morbidities in those with alcohol misuse.

NICE Guidelines advise that alcohol misuse is treated first as this may lead to significant improvement in depression and anxiety. If depression or anxiety persists after four weeks of abstinence from alcohol, it may warrant additional clinical assessment and management.

It is important to screen for and manage any co-morbid substance misuse (e.g. opioids, cannabis, stimulants). For each substance ask about the quantity used, the frequency and pattern of use, when the substance was last used, the total duration of use, and route of use (injected, oral, snorted, smoked). Assess the individual’s insight into the nature and extent of harm caused by substance misuse and assess their readiness/motivation for change.

Physical health complications that might arise secondary to prolonged excess alcohol consumption include:

- Gastrointestinal complications: chronic gastritis, gastro-oesophageal reflux, stomach ulcers, increased risk of GI bleeding, Mallory-Weiss tear, alcohol-related liver disease, alcohol-related pancreatitis.

- Related malignancies: oropharyngeal, oesophageal, stomach, liver, pancreas, colorectal, and breast cancer.

- Neurological complications: alcohol-related brain damage (memory loss, mood, and behavioural changes), peripheral neuropathy.

- Cardiovascular issues: arrhythmia, hypertension, cardiomyopathy, coronary heart disease, stroke.

- Malnutrition

Prognosis

Alcohol dependence is a chronic relapsing-remitting disorder that has negative physical, psychological, economic, and social consequences.

Among young people aged 15-49 years, alcohol is the leading cause of ill health, disability, and death. Relapse of alcohol use disorder is common, especially in the first 12 months after starting treatment.

Last updated: January 2024

References:

DSM-V

Alcohol units - NHS

Ewing JA; Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984 Oct 12 252(14):1905-7.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test - Guidelines for Use in Primary Care, 2nd Edition; World Health Organization

Alcohol Withdrawal Assessment Scoring Guidelines

Recommendations | Alcohol-use disorders: diagnosis and management of physical complications | Guidance | NICE

Alcohol dependence | Treatment summaries | BNF | NICE

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback