Binge eating disorder

Notes

Introduction

Eating disorders are typically characterised by a disordered relationship with food and body image.

Binge eating disorder is characterised by recurrent episodes of binge eating. A binge is defined as consuming an abnormally large amount of food in a relatively short period of time, which is associated with a sense of loss of control. Individuals often eat rapidly, in secret, and to the point of physical discomfort. After the binge, the individual often feels guilty, disgusted, or low in mood.

In binge eating disorder, unlike bulimia nervosa, the individual does not engage in inappropriate compensatory behaviours in response to a binge with the aim of preventing weight gain.

Epidemiology

Epidemiological studies on eating disorders often show significant variation in prevalence and incidence rates.

It is likely that epidemiological data on eating disorders is often underestimated, as many individuals struggling with an eating disorder do not present to health services. The estimated lifetime prevalence of binge eating disorder is approximately 2% for females and 0.3% for males. The National Eating Disorders Association has some excellent information on statistics and epidemiology around eating disorders such as binge eating disorder.

Aetiology & risk factors

The aetiology of binge eating disorder is likely to be multifactorial and include environmental, neurobiological and genetic factors.

Risk factors for binge eating disorder include:

- Female sex

- Family history of weight concerns or eating problems

- Co-morbid mental health disorder (e.g. depression, anxiety): episodes of binge eating may be triggered by negative emotions and aim to provide relief/distraction from them.

- Co-morbid substance misuse

- Co-morbid impulse control disorder (e.g. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder)

- Childhood obesity

- Dieting may play a role in the development of binge eating disorder, as food restriction can result in overeating

- Stressful life events: history of physical/sexual abuse, family conflict

- Mu-opioid receptor and dopamine receptor genes are thought to play a role

Studies have attempted to explain the pathophysiology of binge eating disorder, likening the neurobiology to that of substance use disorder. Recurrent binge eating behaviours are thought to be related to a difficulty in inhibitory control and reward processing. Neuroimaging studies have shown hypoactivity in the prefrontal cortex in individuals with binge eating disorder. The pre-frontal cortex is a region of the brain that enables the individual to exercise impulse control.

Diagnosis

Both DSM-V and ICD-11 can be used as frameworks to aid the clinical diagnosis of binge eating disorder.

Below the diagnosis of binge eating disorder is outlined using DSM-V criteria:

Recurrent episodes of binge eating, characterised by both:

- Eating an abnormally large amount of food in a discrete period of time.

- A sense of lack of control (e.g. a feeling that one cannot stop eating).

The binge-eating episodes are associated with 3 or more of the following:

- Eating much more rapidly than usual.

- Eating until feeling uncomfortably full.

- Eating large amounts of food when not feeling physically hungry.

- Eating alone because of feeling embarrassed by how much one is eating.

- Feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty afterward.

Marked distress regarding binge eating is present. Binge eating occurs, on average, at least once a week for 3 months.

Binge eating:

- is NOT associated with the recurrent use of inappropriate compensatory behaviour as in bulimia nervosa.

- does not occur exclusively during the course of bulimia nervosa or anorexia nervosa.

DSM-V has additional specifiers:

- Partial remission: after full criteria for binge eating disorder were previously met, but now the average frequency of binge eating is less than once a week for a sustained period of time.

- Full remission: after full criteria for binge eating disorder were previously met, but now none of the criteria have been met for a sustained period of time.

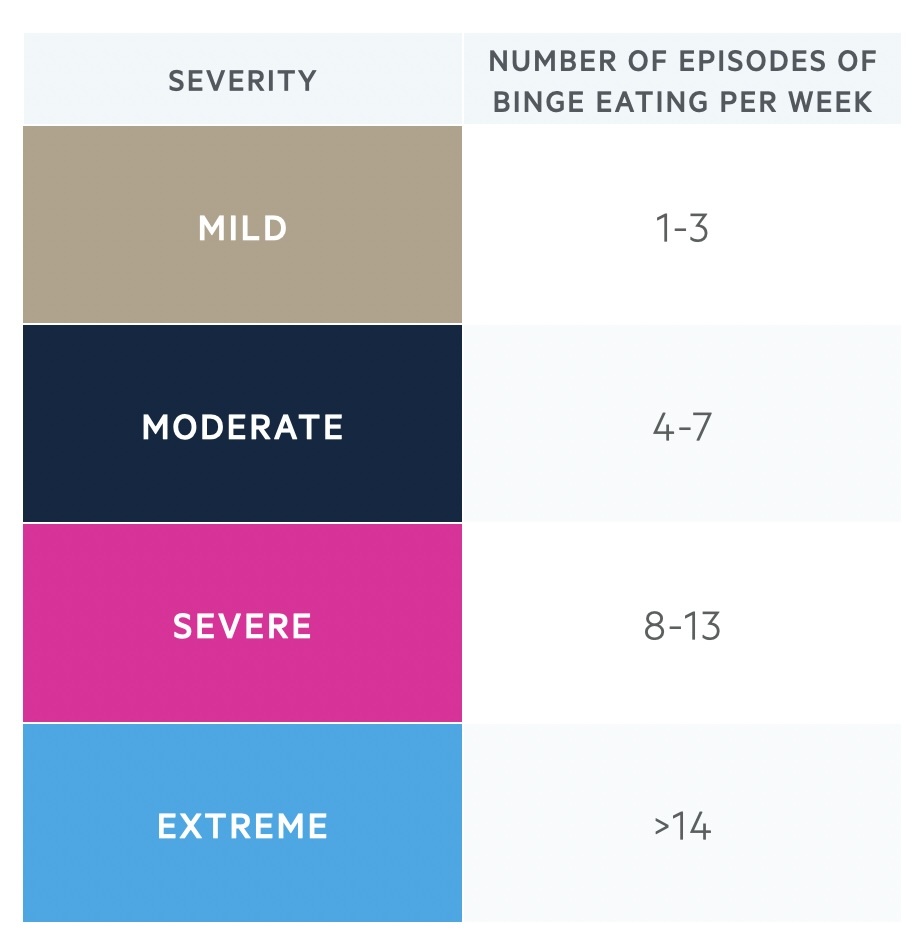

DSM-V also asks that the severity of binge eating disorder is specified, which is based on the frequency of binge eating episodes:

Differential diagnosis

In binge eating disorder, the individual does not engage in any compensatory behaviour that differentiates it from bulimia nervosa.

- Bulimia nervosa: in bulimia nervosa, the individual engages in episodes of binge eating followed by inappropriate compensatory behaviours to avoid weight gain. In binge eating disorder, the individual does not engage in any compensatory behaviours.

- Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED): an individual might be diagnosed with OSFED, where some but not all of the criteria for binge eating disorder are met. In other words, if the binge eating behaviour doesn’t meet the criteria for frequency (once a week) or duration (>3 months) of binge eating disorder.

- Atypical depression: typically depression is associated with loss of appetite and weight loss, however in atypical depression there is often increased appetite resulting in binge eating and weight gain.

- Kleine-Levin syndrome: this is a rare neurological disorder characterised by recurring episodes of hypersomnia accompanied by compulsive eating and hypersexuality.

- Nutritional deficiency: may be the underlying driving factor for binge eating behaviour.

Management

Eating disorders, like binge eating disorder, are mainly managed with talking therapies.

In the UK, eating disorders are mainly managed with talking therapies and referral to Secondary Care Eating Disorder Services may be required for further specialist management.

There are no medications licensed in the UK for the treatment of binge eating disorder. If there is co-morbid depression or anxiety, the individual may benefit from an SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor).

It is important to note that psychological treatments for binge eating disorder have a limited effect on body weight and weight loss is not a goal of therapy.

Psychological interventions

Three predominant psychological interventions could be offered to patients with binge eating disorder:

- Step 1 - Evidence-based guided self-help programme: involves the individual working their way through a self-help book about binge eating disorder and having short sessions with a therapist. Self-help materials are based on the principles of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and individuals are offered 4-9 sessions lasting 20 minutes each over 16 weeks.

- Step 2 - Group eating-disorder-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT-ED): individuals engaging in group CBT-ED are offered 16 sessions of 90 minutes over 16 weeks (4 months).

- Step 3 - Individual eating-disorder-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT-ED): a course of individual CBT-ED typically consists of 16 to 20 weekly sessions.

CBT-ED for binge-eating disorder

There is a good evidence base for CBT-ED for the treatment of people with eating disorders. In both group and individual CBT-ED, the initial focus is on gaining an understanding of the difficulties with food and eating and identifying key factors maintaining the disordered eating. The patient will be asked to complete self-monitoring diaries to record eating habits and associated thoughts and feelings.

The therapist will work with the group or individual, to set goals for therapy which might include:

- Establishing regular healthy eating patterns: advise the person to not try to diet or restrict food during treatment, because this is likely to trigger binge eating.

- Ongoing weekly monitoring: this includes binge eating behaviours, dietary intake, and weight.

- Identifying binge eating cues (situations, thoughts, emotions)

- Address body image issues.

- Completion of CBT homework in between sessions.

Towards the end of the course of CBT, the focus will be on relapse prevention and how to manage any setbacks or relapses.

Management of physical health

Striking the balance between psychological treatment of binge eating disorder whilst also attempting to optimise physical health can be challenging. As noted above, psychological treatments for binge eating disorder have a limited effect on body weight and weight loss is not a goal of therapy. Dieting is advised against, as dietary restriction is likely to trigger binge eating and perpetuate the problem. This understandably poses a challenge for managing physical health complications linked to being overweight in those with binge eating disorder.

Those with a binge eating disorder are at risk of metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is a group of comorbid conditions that increase the risk for cardiovascular events. These conditions include:

- Central obesity

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus (high triglycerides, low HDL)

- Hypertension

- Hypercholesterolaemia

Lifestyle interventions for metabolic syndrome may include encouraging regular physical activity and promoting a diet low in saturated fats. The GP might also consider the need for medication to treat high blood glucose levels, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol. Those with binge eating disorder may also develop gastrointestinal disturbance, commonly gastro-oesophageal reflux. The individual may benefit from a regular proton pump inhibitor use such as omeprazole.

Prognosis

The prognosis of binge eating disorder is better than other eating disorders.

The course of binge eating disorder typically consists of cycles of symptom remission and symptom recurrence/relapse. Approximately 70-80% of individuals with binge eating disorder will recover over time. The tendency of binge eating disorders to convert to other eating disorders is very small.

Last updated: January 2024

References:

DSM-V

https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/statistics/

Prevalence in the UK - Beat (beateatingdisorders.org.uk)

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback