Bulimia nervosa

Notes

Introduction

Bulimia nervosa is characterised by a cycle of recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by inappropriate compensatory behaviours to avoid weight gain.

Eating disorders, like bulimia nervosa, are typically characterised by a disordered relationship with food and body image.

A binge is defined as consuming an abnormally large amount of food in a relatively short period of time, which is associated with a sense of loss of control. Individuals often eat rapidly, in secret, and to the point of physical discomfort. After the binge, the individual often feels guilty, disgusted, or low in mood.

Inappropriate compensatory behaviours occur in response to a binge to prevent weight gain. An individual may self-induce vomiting, misuse laxatives, fast, or exercise excessively. These behaviours are sometimes referred to as purging. There is a preoccupation with body shape or weight, and this strongly influences an individual’s self-evaluation and self-worth.

Epidemiology

Epidemiological studies on eating disorders often show significant variation in prevalence and incidence rates.

It is likely that epidemiological data is often underestimated, as many individuals struggling with an eating disorder do not present to health services.

The peak age of onset for bulimia nervosa is in late adolescence to young adulthood (age 15 to 25 years). Studies suggest that 4 in 100 females are thought to suffer from bulimia nervosa at some point in their lives. Females are about 4 times as likely to be diagnosed with bulimia nervosa compared to males. Transgender adolescents and young adults are thought to be at higher risk of developing an eating disorder and further studies are needed to quantify this increased risk.

The National Eating Disorders Association has some excellent information on statistics and epidemiology around eating disorders such as Bulimia.

Aetiology & risk factors

The aetiology of bulimia nervosa is likely to be multifactorial and include environmental and genetic factors.

The risk factors for bulimia nervosa include:

- Female sex.

- Age: adolescents and young adults.

- Family history: eating disorders and/or mental illness.

- Co-morbid mental health disorder: depression, anxiety, and substance misuse.

- Co-morbid impulse control disorder (e.g. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder).

- History of dieting behaviour/restrictive eating: even being in an environment where others are dieting can put individuals at risk.

- Socio-cultural factors: for example, occupational pressures to have a low body weight (e.g. dancers, models, athletes).

- History of sexual abuse.

Screening for eating disorders

The SCOFF questionnaire is commonly used to screen individuals for eating disorders.

The SCOFF questionnaire is a simple tool that can be used to help identify those who might be suffering from an eating disorder. The questionnaire encompasses five simple questions:

- S – Do you ever make yourself Sick because you feel uncomfortably full?

- C – Do you worry that you have lost Control over how much you eat?

- O – Have you recently lost more than One stone in a 3-month period?

- F – Do you believe yourself to be Fat when others say you are too thin?

- F – Would you say that Food dominates your life?

Two or more positive answers to the above questions are suggestive of bulimia nervosa or anorexia nervosa and further clinical attention is therefore warranted.

Diagnosis

Bulimia nervosa is characterised by recurrent episodes of binge eating followed by compensatory behaviours to prevent weight gain.

Both the DSM-V and ICD-11 can be used as frameworks to aid the clinical diagnosis of bulimia nervosa. The DSM-V criteria below can be used to help make the diagnosis of bulimia nervosa:

Recurrent episodes of binge eating, characterised by both:

- Eating an abnormally large amount of food in a discrete period of time.

- A sense of lack of control (e.g. a feeling that one cannot stop eating).

Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviours to prevent weight gain:

- Self-induced vomiting.

- Misuse of laxatives, diuretics or diet pills.

- Fasting.

- Excessive exercise.

The combination of binging and inappropriate compensatory behaviours occurs, on average, at least once a week for 3 months.

Body shape and weight strongly influence self-evaluation, and the disturbance does not occur exclusively during episodes of anorexia nervosa.

DSM-V has additional specifiers:

- Partial remission: full criteria for bulimia nervosa were previously met, but now only some criteria have been met for a sustained period of time.

- Full remission: full criteria for bulimia nervosa were previously met, but now none of the criteria have been met for a sustained period of time.

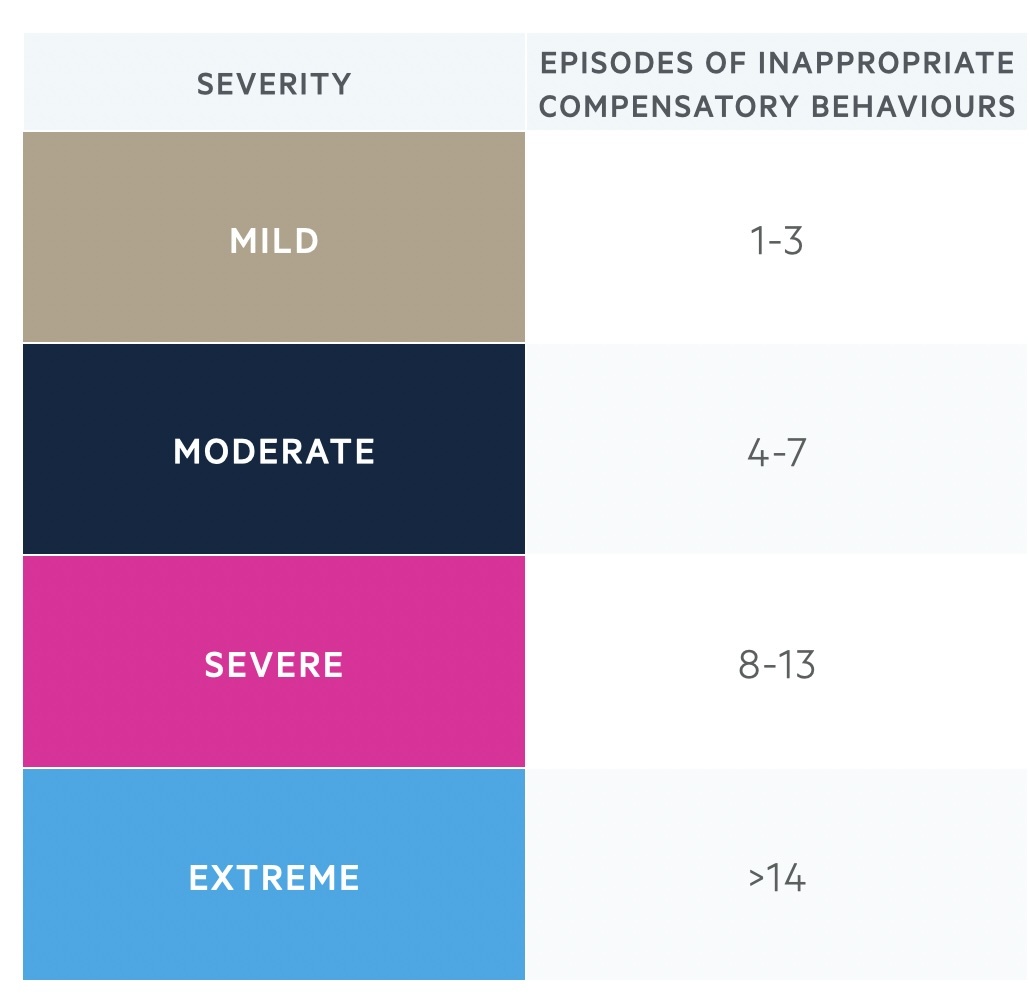

DSM-V also asks that the severity of bulimia nervosa is specified, based on the frequency of inappropriate compensatory behaviours:

Other clinical features

In addition to the above DSM-V criteria, individuals with bulimia nervosa may also experience the following:

- Preoccupied by food and food cravings.

- Feelings of guilt and shame about eating behaviours.

- Bingeing and purging tend to be secretive behaviour: can lead to social isolation.

- Often low mood or symptoms of anxiety.

- May be co-morbid deliberate self-harm or substance misuse.

Possible clinical findings in patients with bulimia nervosa:

- May have normal body weight (can fluctuate).

- Damage from repeated vomiting: dental enamel erosion, mouth ulcers, gum disease, and swollen salivary glands.

- Gastrointestinal disturbance: can include gastro-oesophageal reflux, bloating, and constipation.

- Russell’s sign: calluses on knuckles from self-induced vomiting, where knuckles have scraped against teeth.

Differential diagnosis

In binge eating disorder, there is no compensatory behaviour.

- Binge eating disorder: individuals do not engage in compensatory behaviours after episodes of binge eating.

- Anorexia nervosa, binge-eating/purging type: common features include binge eating and purging behaviours and an undue influence of body weight/shape on self-evaluation. Diagnostic criteria specific to anorexia nervosa include restriction of energy intake leading to a significantly low body weight, not recognising the seriousness of the low body weight and an intense fear of gaining weight.

- Other specified feeding or eating disorders (OSFED): an individual might be diagnosed with OSFED, where some but not all of the criteria for bulimia nervosa are met. In other words, if the compensatory behaviour doesn’t meet the criteria for frequency (once a week) or duration (>3 months) of bulimia nervosa.

Management

Eating disorders, like bulimia nervosa, are mainly managed with talking therapies.

In the UK, eating disorders are mainly managed with talking therapies and referral to Secondary Care Eating Disorder Services may be required for further specialist management. Monitoring of general medical problems is usually facilitated in primary care by the GP. Treatment of bulimia nervosa tends to take place on an outpatient basis unless risks to physical or mental health necessitate inpatient admission.

Psychological interventions (adults)

Psychological interventions for bulimia nervosa can include:

- Step 1 - Bulimia-nervosa-focused guided self-help programmes

- Step 2 - Eating-disorder-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT-ED)

In self-help programmes, the individual works their way through books about bulimia nervosa and has short sessions with a therapist. Individuals are offered 4-9 sessions lasting 20 minutes each over 16 weeks. If there has been no help with guided self-help after 4 weeks of the programme, clinicians should consider CBT-ED.

Eating-disorder-focused cognitive behavioural therapy

CBT focuses on the link between our thoughts, behaviours and emotions. Challenging negative thoughts and changing unhelpful behaviours can have a positive impact on how a person feels. There is a good evidence base for CBT-ED for the treatment of people with eating disorders. Individuals are offered 20 sessions over 20 weeks.

Initially, the focus in CBT-ED is on gaining an understanding of the individual’s difficulties with food and eating, and identifying key factors maintaining the disordered eating. The patient might be asked to start by completing questionnaires and self-monitoring diaries to record eating habits and associated thoughts and feelings.

The therapist and patient will then work together to set goals for therapy which might include:

- Establishing regular healthy eating patterns: advise the person to not try to diet or restrict food during treatment, because this is likely to trigger binge eating.

- Ongoing weekly monitoring: this includes binge eating behaviours, dietary intake, and weight.

- Identifying binge eating cues (situations, thoughts, emotions)

- Address body image issues.

- Completion of CBT homework in between sessions.

Towards the end of the course of CBT, the focus will be on relapse prevention and how to manage any setbacks or relapses.

Psychological interventions (children and young people)

For children and young people, family therapy is usually the first-line treatment:

- Step 1 - Bulimia-nervosa-focused family therapy (FT-BN)

- Step 2 - Individual eating-disorder-focused cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT-ED)

FT-BN is usually offered to children and young people with bulimia nervosa. It usually involves 18-20 sessions over 6 months. In family therapy sessions, the therapist will encourage exploration of how the eating disorder has affected the individual and their family. The therapist will provide education about the eating disorder and explore ways in which the family might be able to support the child. This involves supporting the child to develop and maintain regular healthy eating habits and to change any disordered eating behaviours (such as binge eating/purging). The family will also have a role to play in planning for relapse prevention towards the end of therapy.

Children and young people with bulimia nervosa may instead be offered CBT-ED. They are typically offered 18 sessions with a therapist over 6 months. There may be additional sessions offered to include parents or carers. CBT-ED for children and young people follows similar principles to those outlined above in CBT-ED for adults.

Pharmacological treatments

High-dose fluoxetine (60mg once daily) is the only licensed medication for adults with bulimia nervosa. This cannot be the sole treatment of bulimia and needs to be used alongside psychological therapy. High-dose fluoxetine is thought to reduce the urge to binge eat and studies have shown it reduces the frequency of binge eating and vomiting. Fluoxetine is an SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) and is also likely to be beneficial for any co-morbid anxiety disorders or depression.

Physical health monitoring

For those with a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa, consider the need for regular physical health checks. This will usually be carried out in primary care by the GP. It is important to monitor the individual’s weight and BMI, and if necessary, support them to reach a healthy BMI. Consider whether the individual would benefit from dietician input with regard to meal planning and optimising their nutrition.

It is also important to consider blood tests for individuals who are regularly engaging in purging behaviours to check their electrolytes. The most likely electrolyte abnormality in bulimia nervosa is hypokalaemia. This can put people at risk of abnormal heart rhythms, so performing an ECG may also be indicated. Typical ECG changes in hypokalaemia include increased P wave amplitude, a prolonged PR interval, ST depression, T wave flattening/inversion and prominent U waves.

The following advice can be given to patients who are self-inducing vomiting:

- Avoid highly acidic foods and drinks.

- Avoid brushing teeth immediately after vomiting.

- Rinse with non-acid mouthwash after vomiting.

- Give advice on the importance of regular dental review.

Advise people with an eating disorder who are misusing laxatives or diuretics that laxatives and diuretics DO NOT reduce calorie absorption and so do not help with weight loss. Excessive use of laxatives and diuretics can also be dangerous and lead to electrolyte imbalances.

Risk assessment

The risk assessment is a key component of the management plan for any mental health disorder. Risks to mental health and physical health need to be considered in those with an eating disorder. There may be a co-morbid mood disorder and it is important that the risk of deliberate self-harm and suicidal ideation is under regular review. Risks to self may increase as the individual begins to address and change some of the disordered eating behaviours.

Information and support

It is important to note that families and carers of an individual with an eating disorder may experience difficulties and benefit from support of their own. It can be helpful to provide written information and to signpost families to useful resources, such as the Beat Eating Disorders website. Given that the onset of bulimia nervosa is often in late adolescence, it is not unlikely that the individual and their family will need support transitioning between child and adult eating disorder services. Be aware that this transition is likely to impact their recovery and take steps to provide as much continuity of care as possible to minimise this risk.

Prognosis

Bulimia nervosa is associated with better recovery rates and lower mortality than anorexia nervosa.

The course of bulimia nervosa typically consists of cycles of symptom remission and relapse. Studies demonstrate differing outcomes for those who receive treatment for bulimia nervosa. On average, half make a full recovery, a quarter improve considerably, and another quarter continue to struggle with bulimia nervosa in the long term.

Last updated: January 2024

References:

DSM-V

https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/statistics/

Prevalence in the UK - Beat (beateatingdisorders.org.uk)

The outcome of bulimia nervosa: findings from one-quarter century of research

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback