Depression

Notes

Introduction

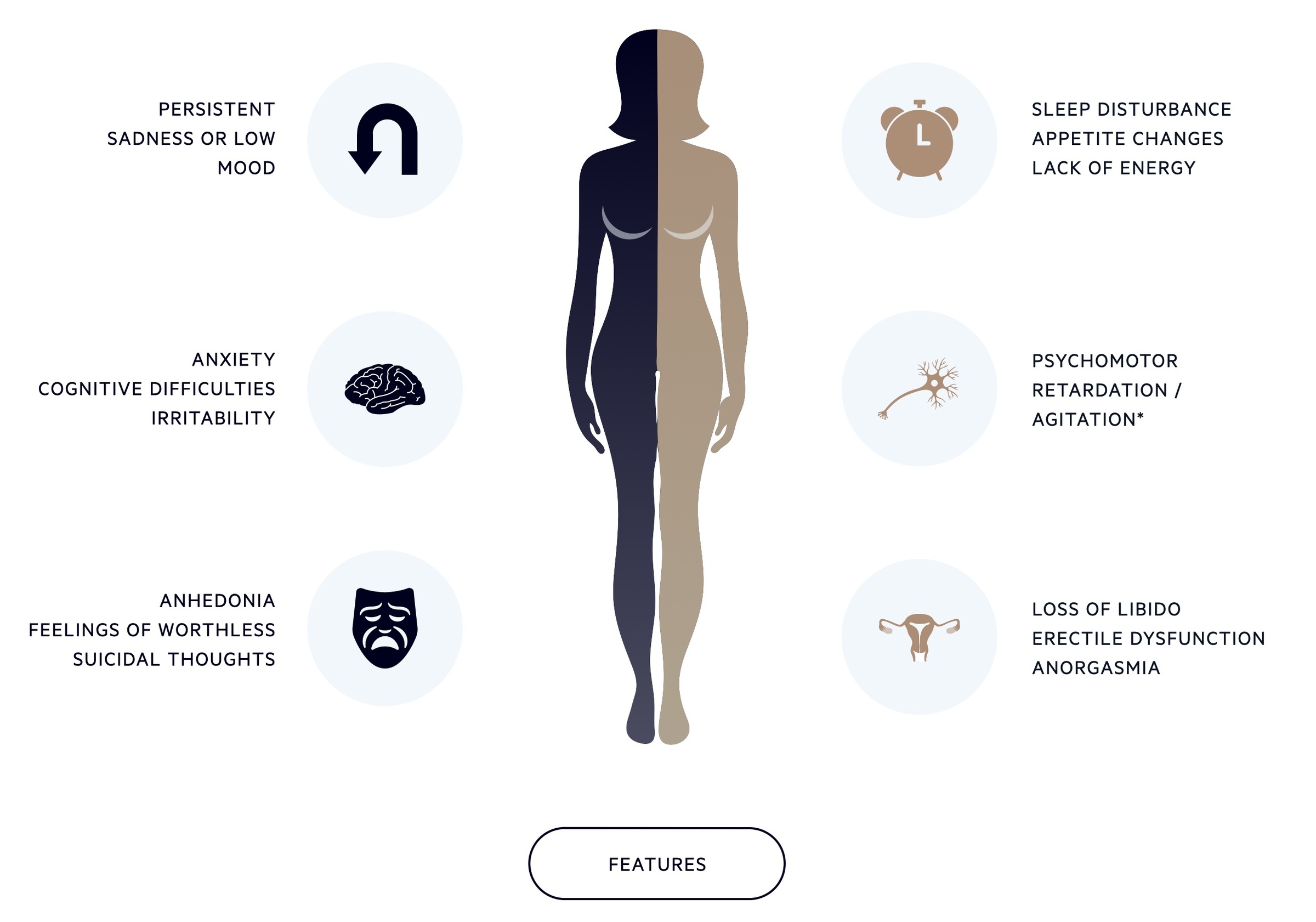

Depression is a common condition characterised by low mood, anhedonia and a range of accompanying features.

Many people will experience depression, or another mental health disease, during their lifetime. A renewed public health effort has put depression and mental illness at the forefront of public life and has helped to reduce the stigma that may have been associated with it.

Despite this focus on mental health, many of these conditions still go under-recognised and under-treated. Here we will give an overview of depression in adults, how its classified and some of the current therapies available.

While a NICE guideline does exist for depression in adults, it was first published in 2009. NICE is in the process of creating an updated guideline, but it remains in the draft stages and has been the subject of some controversy. An updated version of NICE clinical guidance 90 can be found here.

There are two major classification systems used:

- ICD-10: The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) is a classification of human disease created by the World Health Organisation.

- DSM-V: The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) now in its fifth edition is a classification of mental health disorders published by the American Psychiatric Association. NICE CG 90 uses DSM-IV, the fourth edition though the NICE clinical knowledge summary uses DSM-V.

Epidemiology

Depression is common, according to the World Health Organisation it affects 264 million people around the world.

It is a leading cause of disability and contributes significantly to the global burden of disease. The UK is no different.

In statistics published by the Mental Health Foundation in 2016, just under 20% of adults in the UK showed symptoms of anxiety or depression. A third of people who self-identified as having a mental health problem had never received a diagnosis from a professional.

Risk factors

Though the aetiology of depression is poorly understood, a number of risk factors have been identified.

- Chronic conditions

- History of depression or other mental health illness

- Female sex

- Medication (e.g. corticosteroids)

- Older age

- Recent childbirth

- Psychosocial issues (e.g. unemployment, homelessness)

- Genetic factors

- History of childhood abuse

- History of head trauma

Definition and classification

The DSM-V provides a classification framework for depressive disorders.

The below criteria describe a framework that can be used to help classify and diagnose depression. It must be remembered that each patient must be approached as an individual and any assessment made in a holistic manner.

Depression (or Major Depressive Disorder) is defined by DSM-V as the presence of five of the following symptoms, for at least two weeks, one of which should be low mood or loss of interest/pleasure:

- Low mood

- Loss of interest or pleasure

- Significant weight change

- Insomnia or hypersomnia (sleep disturbance)

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation

- Fatigue

- Feelings of worthlessness

- Diminished concentration

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or specific plan for committing suicide

In addition, the following must be present:

- Symptoms cause significant distress and impair normal function

- Symptoms or episode not caused by another condition of substance

- Episode no better explained by other mental health illnesses

- No episodes of mania or hypomania

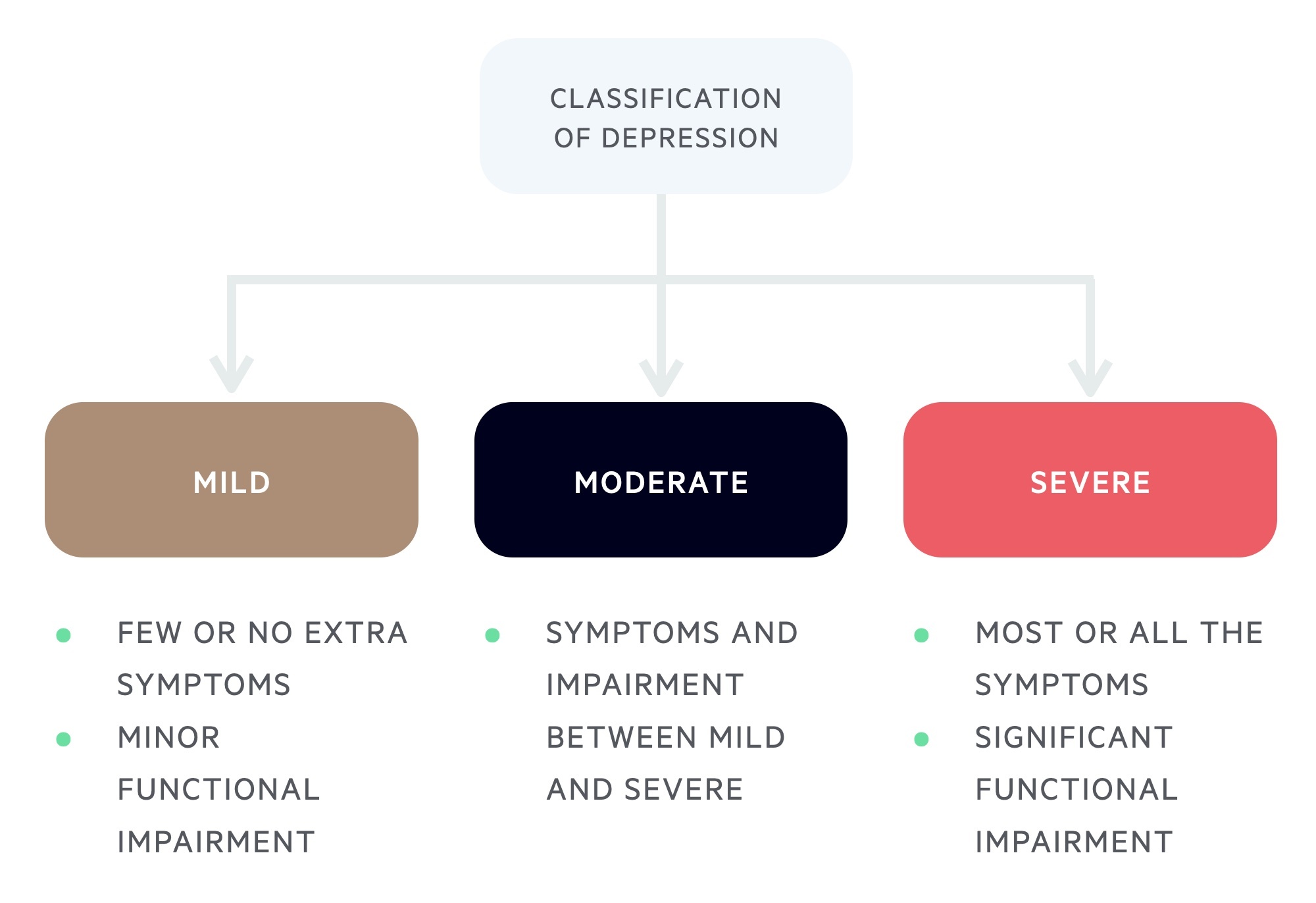

Depression may then be classified in one of three categories of severity

- Mild: few or no extra symptoms beyond the five to meet the diagnostic criteria

- Moderate: symptoms and impairment between mild and severe

- Severe: most or all the symptoms (see above) causing marked functional impairment with or without psychotic features

Subthreshold depressive symptoms

This describes patients with some features of depression not meeting the above definition:

- Subthreshold depressive symptoms: describes patients with a number of depressive symptoms (see above) not meeting the criteria described above.

- Persistent subthreshold depressive symptoms: describes subthreshold depressive symptoms that persist for two years or more.

Investigations

Although depression is largely a clinical diagnosis, secondary causes or contributory factors may need to be screened for.

Tests to consider include:

- FBC

- LFTs

- Bone profile

- HbA1c

- Thyroid function tests

- Serum cortisol

- B12 / folate

- Syphilis serology

Initial Management

The management of depression is multifaceted and should be tailored to the individual patient.

Assess suicide risk

Adult patients should be asked about suicidal thoughts and ideation. This is a key part of any assessment. Any patient deemed to be at risk should be discussed immediately with the local specialist mental health services for further assessment and a management plan.

Subthreshold or mild-moderate depression

- Psychosocial therapies: consider and discuss low-intensity psychosocial intervention and group CBT.

- Antidepressants: consider in those with a history of moderate-severe depression, persistent subthreshold symptoms or subthreshold/mild depression that does not respond to non-pharmacological interventions. Also consider in those in whom mild depression is complicating the management of other conditions.

- Sleep hygiene: routine sleep hygiene advice should be given. Some find mindfulness techniques help. There are lots of resources available to aid this (e.g bemindfulonline.com)

- Follow-up: early follow-up (within 1-2 weeks) and ongoing review tailored to each patient.

Moderate-severe depression

- Psychological therapies: offer high-intensity psychosocial intervention.

- Antidepressants: offer antidepressant therapy.

- Sleep hygiene: routine sleep hygiene advice should be given. Some find mindfulness techniques help. There are lots of resources available to aid this (e.g bemindfulonline.com).

- Follow-up: early follow-up (within 1-2 weeks) and ongoing review tailored to each patient.

NOTE: SSRIs and SNRIs have been implicated in an increased risk of suicide, suicidal ideation and self-harm, particularly below the age of 30. All patients commenced in this age group should have review within one week of starting therapy with weekly reviews for at least one month.

Antidepressants

The initiation of antidepressants must be taken as a collaborative decision based upon guidelines and discussion with the patient.

The choice of antidepressant depends on a number of factors:

- Toxicity: avoid certain antidepressants in patients with suicide risk or a history of overdose (e.g. tricyclics, venlafaxine).

- Side effects: antidepressants may cause weight gain, sexual dysfunction.

- Interactions: review any current medication and potential interactions.

In general, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) like citalopram will be offered first line. Sertraline may be used in co-morbid patients as it has fewer drug-drug interactions. Consider the need for PPI cover, particularly in those taking NSAIDs.

A discussion must be had regarding the nature of antidepressants. The risk of suicide and overdose should be explained. Antidepressants often take time to be effective and initially anxiety may worsen. Once commenced, the advice in general is to continue for at least six months. They should not be stopped without discussion with a medical professional.

Psychological therapies

A number of psychosocial and psychological therapies are available to patients.

- Low-intensity psychosocial interventions: there are a number of options that can be offered to patients. These include computerised CBT and self-help therapy based upon CBT principles. Group-based physical activity may also be offered.

- Group-based CBT: may be offered to those with persistent subthreshold and mild to moderate depression.

- High-intensity psychological interventions: normally offered to those with moderate to severe depression. May consist of individual CBT, interpersonal activity, couples therapy and behavioural activation.

- Counselling and short-term psychodynamic therapy: may be offered to those who decline high-intensity psychological interventions or antidepressants.

Ongoing management

Follow-up is important to allow assessment of suicide risk, response to treatment and any other changes that may occur.

Reassess suicide risk

Continue to assess suicide risk and escalate as appropriate. Review and address any safeguarding concerns.

Those deemed to be at risk of suicide should be discussed with local mental health services. If they do not require admission, review should be frequent.

Treatment response

In general, it takes two weeks for the effect of antidepressants to become apparent.

If after a month the response is minimal, consider dose adjustment or switching drug class.

Psychological and psychosocial therapies normally have a set course, patients should be monitored during this to evaluate for benefit.

Discontinuing antidepressants

As a general rule antidepressants should be continued for a minimum of six months. Of course, adverse reactions or side effects may prevent this.

At six months a discussion should be had with appropriate patients about stopping antidepressants and the potential risks involved. Factors that help guide decision-making include current symptoms, previous mental health history and other exacerbating factors.

If medication is continued consider psychological therapies as an adjunct and the need to refer to specialist services.

Ongoing use should be again reviewed at two years (and prior if appropriate). Again a holistic view must be taken and the benefits and risk of continuing and discontinuing treatment evaluated.

Typically antidepressants will be withdrawn gradually over a four-week period to reduce the incidence and severity of discontinuation symptoms.

NOTE: Stopping and switching antidepressants must be done with caution, and according to guidelines.

Last updated: April 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback