Personality disorders

Notes

Introduction

Personality is described as the "combination of characteristics or qualities that form an individual's distinctive character".

Personality describes an individual’s enduring personal characteristics, including their unique patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving. Personalities are thought to be formed from a combination of a person’s innate temperament, environmental factors, and life experiences.

Personality disorders, commonly abbreviated to "PD", occur when personality traits deviate significantly from the norm and manifest in harmful patterns of thinking, feeling, behaving, and interacting with others. Personality disorders tend to become evident during late adolescence or early adulthood but are not usually diagnosed under the age of 18 years old. They cause the individual significant distress and result in difficulties in multiple areas of a person’s life.

Features of personality disorders vary, depending on the specific type. This summary overview discusses the different types, characteristic features, and broad management.

Epidemiology

It is estimated that PDs remain underdiagnosed.

Individuals with undiagnosed PD tend to initially present to services for treatment of mood or anxiety disorders. The underlying diagnosis of PD often only becomes apparent after the individual fails to respond to treatment.

Prevalence estimates vary but studies suggest that approximately 1 in 20 people in the UK have a PD. The two most commonly diagnosed PDs are antisocial PD and borderline PD. Other PDs may be more prevalent amongst the general population, but individuals with antisocial and borderline PD are most likely to come to the attention of services and hence receive a diagnosis.

The prevalence of borderline PD in the UK general population is 1-2%. It is estimated that 20% of patients within inpatient psychiatric wards are thought to have a diagnosis of borderline PD. It is more common in females than males (3:1), although this might be because women are more likely to seek treatment.

The prevalence of antisocial PD in the UK general population is 0.6%. It is more common in males than females (5:1). Approximately half or more of male prisoners are thought to meet the criteria for a diagnosis of antisocial PD.

Aetiology & risk factors

The exact aetiology of personality disorders is uncertain.

PDs are thought to relate to a complex interaction of multiple factors including early traumatic events, childhood psychological traits, and family history.

- Traumatic events in early life: these may include childhood abuse (physical, emotional, sexual abuse or neglect) and early parental loss or separation. Maladaptive patterns of thinking, feeling, behaving, and interacting with others are thought to develop in response to dysfunctional early environments that prevent normal development.

- Childhood temperament and psychological traits.

- Family history: no specific genetic factors have been identified but there is often a family history of mental health disorders.

Clinical assessment

A prolonged clinical assessment of an individual with the help of a clinical tool (e.g. SCID-5-PD) is usually required to make a diagnosis of PD.

A diagnosis of PD is usually made by a psychiatrist after a prolonged individual assessment. Where one is suspected, several tools can be used to aid the diagnosis. One such tool used in the NHS is the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorders (SCID-5-PD). This is a semi-structured interview administered by a clinician or trained mental health professional that assesses for traits of the 10 DSM-V personality disorders (detailed below). There are different versions of SCID, including those used for research purposes, clinical trials, and a briefer clinician version that covers the diagnoses most often seen in clinical settings.

Clinical features & diagnosis

The diagnosis and classification of personality disorders continue to evolve.

There are some differences in the way PDs are classified depending on the classification system used.

- DSM-V: 10 PDs into 3 clusters based on similar characteristics.

- ICD-10: division of PDs into distinct types, but not into clusters.

- ICD-11: a single diagnosis of PD based on central manifestations characterised of most previously categorised disorders.

ICD-11 classification and diagnosis

Within the ICD-11, it outlines the central manifestations of PD as impairments in two key areas:

- Self-functioning (e.g. identity, self-worth, capacity for self-direction)

- Interpersonal functioning (e.g. developing and maintaining close relationships, managing conflict, understanding others’ perspectives)

Impairment in these two areas occurs in association with maladaptive patterns of cognition, emotional experience, emotional expression, and behaviour.

The ICD-11 then applies specifiers to determine the severity of PD, personality trait domains (e.g. negative affectivity, disinhibition), and an additional borderline pattern specifier. This will have major implications for clinical practice but has not yet been implemented. Therefore, we will focus on the categories currently used in the DSM-V criteria (see below).

DSM-V classification and diagnosis

The general diagnosis of a personality disorder is outlined using DSM-V criteria below:

An enduring pattern of inner experience and behaviour that deviates markedly from expectations of the individual’s culture. This pattern is manifested in ≥2 of the following areas:

- Cognition: ways of perceiving and interpreting self, other people, and events.

- Affectivity: the range, intensity, lability, and appropriateness of emotional response.

- Interpersonal functioning

- Impulse control

The pattern is said to be:

- Inflexible and pervasive across a broad range of personal and social situations.

- Associated with clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning (social, occupational, or other important area of functioning).

- Stable and of long duration: can be traced back to adolescence or early adulthood.

- Not better explained by another mental disorder.

- Not due to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition.

Clinicians are advised not to make a diagnosis of PD in children and young people. However, the DSM-V states that a diagnosis can be made in someone under the age of 18 if the features have been present for at least a year. The exception to this is antisocial PD which cannot be diagnosed under the age of 18.

Personality disorder types

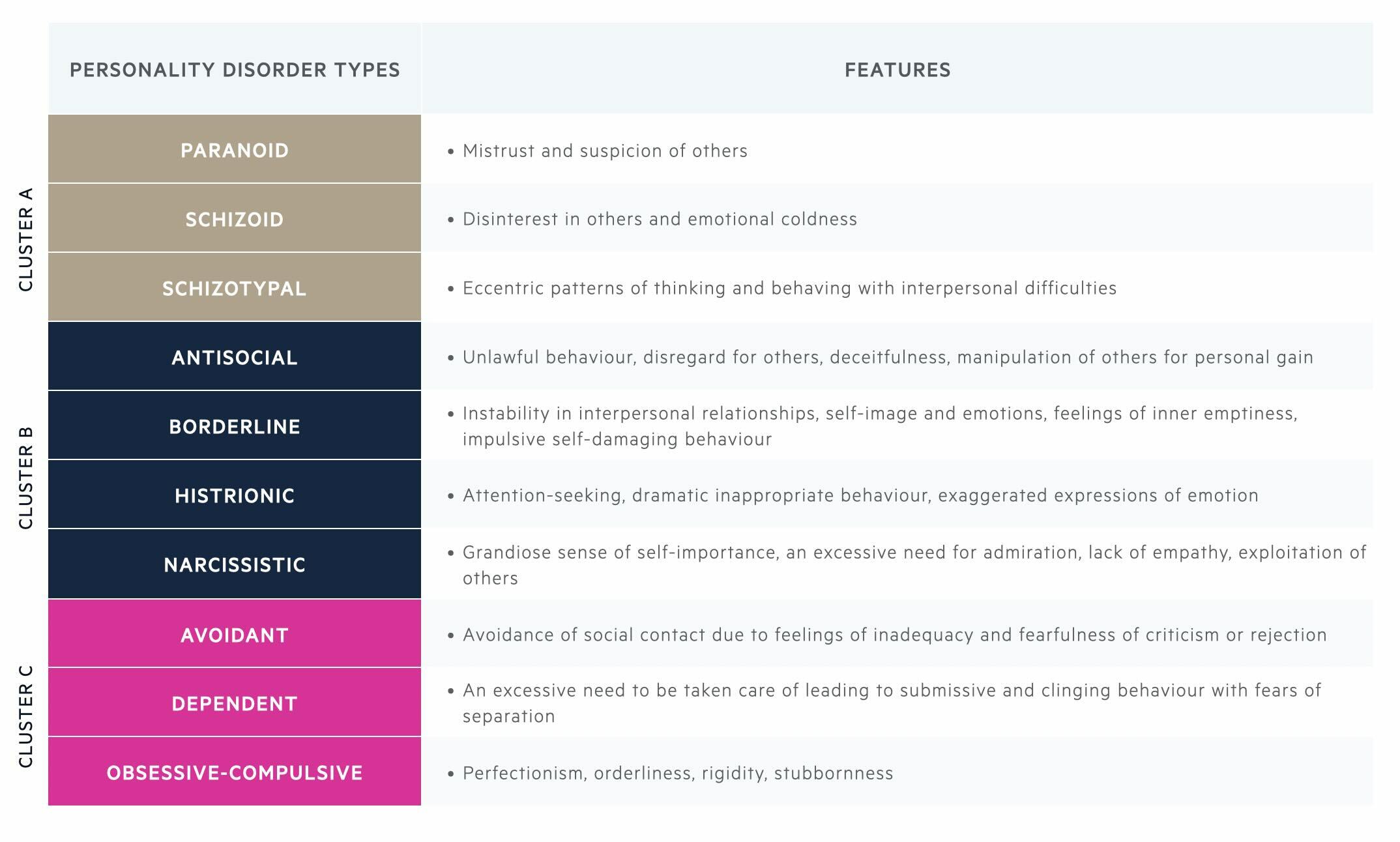

The DSM-V groups 10 personality disorders into 3 clusters based on similar characteristics.

- Cluster A: odd or eccentric patterns of thinking and behaving with interpersonal difficulties.

- Cluster B: dramatic, emotional, impulsive, or erratic patterns of thinking and behaving with interpersonal difficulties.

- Cluster C: anxious fearful patterns of thinking and behaving with interpersonal difficulties.

Antisocial personality disorder

Antisocial personality disorder is characterised by a pervasive pattern of disregard for, and violation of, the rights of others.

Among individuals with antisocial personality disorder, there is usually repeated unlawful, deceitful and manipulative behaviour for personal gain. Behaviour is often reckless and aggressive and there is a lack of remorse for having hurt or mistreated others. The individual must be at least 18 years old and the onset of behaviour must have been before age 15 years (meeting the criteria for conduct disorder).

NOTE: Conduct disorder usually begins in childhood or adolescence and is characterised by aggressive, rule-breaking behaviours that lead to conflict with adults and peers. Up to 50% of adolescents with conduct disorder may develop antisocial personality disorder in adulthood.

Borderline personality disorder

Borderline personality disorder is characterised by instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and emotions with impulsive behaviours.

Among individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD), there is a pattern of unstable intense interpersonal relationships characterised by alternating between extremes of idealisation (e.g. only seeing exaggerated positive qualities and seeing someone as all good) and devaluation (e.g. only seeing exaggerated negative qualities and seeing someone as all bad).

There may also be frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. The individual often has chronic feelings of emptiness, frequent sudden changes in mood, and difficulty controlling anger. There may be impulsive potentially self-damaging behaviours (e.g. spending, sex, substance abuse, reckless driving, binge eating) and recurrent suicidal or self-mutilating behaviours. In times of extreme stress, they may experience transient paranoid ideas or severe dissociative symptoms (e.g. feeling disconnected from oneself or one’s environment).

NOTE: the ICD-10 refers to this as emotionally unstable personality disorder.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of a personality disorder broadly depends on the associated cluster (A, B, or C) according to the DSM-V classification.

For cluster A personality disorders (paranoid, schizoid and schizotypal), the differential diagnosis includes schizophrenia, depression with psychotic features, bipolar affective disorder, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). In psychosis, there is a loss of contact with reality and paranoid ideas are believed with delusional intensity. Other possible overlapping features include social isolation, interpersonal difficulties, lack of interest in activities, odd beliefs eccentric appearance, speech or behaviour.

For cluster B personality disorders (antisocial, borderline, histrionic, narcissistic) a key differential diagnosis is bipolar affective disorder. Emotions may appear exaggerated. Behaviour may be impulsive, risky, inappropriate or overly sexual. There may be inflated self-esteem or grandiosity as in narcissistic PD. Complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common co-morbidity or differential diagnosis for those with borderline PD. Both are characterised by emotional dysregulation, negative self-perception and relationship difficulties. In complex PTSD there will additionally be a clear precipitating trauma, intrusive memories or flashbacks of the trauma, avoidance of reminders for the trauma and hypervigilance to threat.

For cluster C personality disorders (avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive), which are characterised by anxious and fearful patterns of thoughts and behaviours, the differential diagnoses include anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Social anxiety disorder is a key differential for avoidant PD, as both are characterised by a fear of negative judgement in social situations and avoidance. ASD is a differential diagnosis for obsessive-compulsive PD as in both there is rigidity, inflexibility and interpersonal difficulties.

Management

In clinical practice, you are most likely to come across borderline PD.

NICE Guidelines in the UK are only available for borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder. In clinical practice, you are most likely to come across patients with borderline PD, so this management section focuses on the management of borderline PD. Many treatment principles apply to the management of all personality disorders.

Psychological therapies

Psychological therapies are the mainstay of treatment for PDs and are most effective if the patient is seeking treatment and there is motivation to change. Brief psychological intervention (of less than 3 months’ duration) is not advised for those with a PD.

Psychological therapy for borderline PD aims to help the individual:

- Manage feelings of distress, anxiety, anger, and worthlessness.

- Gain insight into maladaptive ways of thinking and behaving.

- Decrease maladaptive behaviours that harm either themselves or others (e.g. deliberate self-harm).

- Build and maintain stable close relationships with others.

Specific psychological therapies for borderline PD can include dialectical behavioural therapy, mentalisation-based therapy, cognitive analytic therapy, and several others.

- Dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT): specifically designed to treat borderline PD and was developed from cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). CBT focuses on changing unhelpful patterns of thinking and behaving. DBT builds on this concept by also focusing on acceptance. “Dialectical” relates to the concept that two opposing things can be true or occur at the same time. For example, accepting oneself whilst at the same time trying to change behaviour might feel contradictory, but DBT teaches that both acceptance and change can be achieved together.DBT encourages the individual to recognise and accept uncomfortable emotions and learn skills to reduce harmful maladaptive behaviours (self-harming, drinking alcohol, binge eating). It is often delivered in group sessions and aims to implement healthier ways of managing emotions.

- Mentalisation-based therapy (MDT): evidence-based treatment for people with borderline personality disorder. Mentalisation is the ability to recognise one’s own thoughts, emotions, and behaviours, and consider that others may think, feel or perceive things differently. Mentalisation is more difficult when a person is feeling emotional distress and those with borderline PD are thought to have a limited capacity for mentalisation. MBT helps the individual develop the capacity for mentalisation, encouraging them to stop and think before reacting to their thoughts or emotions or reacting to what they think another person is thinking or feeling. MBT also helps individuals with borderline PD recognise that they may not be accurately interpreting someone else’s actions or intentions.

- Cognitive analytical therapy (CAT): a type of therapy that focuses on relationship patterns. It is based on the idea that early life experiences influence how people see themselves and relate to others. CAT helps individuals identify and change unhelpful patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving when relating to others.

- Others: Psychodynamic or psychoanalytic therapy (a type of long-term talking therapy that addresses complex deep-seated emotional and relationship problems), art therapies (particularly for those who find it hard to express thoughts and feelings verbally), and therapeutic communities (structured environments where people come together to interact and take part in group therapy over long periods).

Pharmacotherapy

There are no licensed medications to treat personality disorders. Medication can be used to treat co-morbid conditions associated with personality disorders including depression, anxiety, PTSD, and psychosis. Although there are no licensed drugs for this indication, short-term drug treatment is sometimes initiated for people with borderline PD in a crisis. NICE Guidelines advise that the chosen medication should have a low side-effect profile, low addictive properties, minimal potential for misuse, and be relatively safe in overdose. Promethazine (a sedative antihistamine), although not licensed for this use, is sometimes used in clinical practice as it meets these criteria.

Other considerations

Those with a suspected or confirmed borderline PD may be referred to a Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) or a Specialist Personality Disorder Service. If there are significant risks or the person is in crisis, then it may be appropriate to involve a Home Treatment Team (HTT) or consider inpatient psychiatric admission. NICE guidelines for borderline PD highlight the importance of agreeing on the planned length and purpose of admission in advance. Where an individual is detained under the Mental Health Act for compulsory treatment, it is advised that treatment on a voluntary basis is resumed at the earliest opportunity.

NICE Guidelines advise using a Care Programme Approach (CPA) for those with borderline PD. Teams working with people with borderline PD should develop comprehensive care plans in collaboration with the patient. The care plan should:

- Identify the roles and responsibilities of all professionals involved.

- Identify short and long-term treatment goals and detail realistic steps to achieve these.

- Develop a crisis plan that identifies potential triggers, makes note of effective self-management strategies, and details how to access services (including crisis numbers for out-of-hours support).

This care plan should be shared with the patient and their GP and be regularly reviewed. Ongoing risk assessment and risk management is a key management consideration for those with borderline PD. It is important to identify the risks posed to self and others (including the welfare of any dependent children). Risks can be divided into immediate and long-term risks.

With the consent of the individual with borderline PD, encourage the involvement of family and/or carers. These members may benefit from education or additional support. It can be important to consider that families and friends often act in ways that can either reinforce or diminish the patient’s maladaptive thoughts and behaviours. For those with borderline PD, finishing treatment or transitioning from one service to another can be very emotionally challenging and may be associated with increased risk. It is important to provide support around endings or transitions. These should be carefully planned in advance and ideally take place in a gradual structured way with clear communication.

Other important considerations in the assessment and management of those with borderline PD include assessing and treating for comorbid mental disorders (depression, anxiety, PTSD, eating disorders, insomnia, substance misuse).

Prognosis

Antisocial PD is associated with increased morbidity and mortality due to reckless behaviours.

Antisocial and borderline PD traits tend to improve with age. Obsessive-compulsive and schizotypal PD traits are less likely to improve with age and may even become more evident. Both antisocial and borderline personalities disorders are associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality. It is estimated that up to 1 in 10 people with borderline PD die by suicide.

Last updated: January 2024

References:

DSM-V

ICD-10/11

ICD-11 mortality statistics

Antisocial personality disorder: prevention and management: NICE guidance

Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management: NICE guidance

Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback