Self-harm

Notes

Introduction

Self-harm is defined as an intentional act of hurting oneself and is often an expression of or way to cope with emotional distress.

Self-harm is not a mental health condition but can occur in the context of mental health conditions such as depression and borderline personality disorder.

The severity and intention of self-harm acts can vary greatly and can be divided into:

- Non-suicidal self-harm

- Suicidal attempts/acts.

NICE Guidelines divides self-harm into self-poisoning and self-injury:

- Self-poisoning: often involves prescribed or over-the-counter medication. Can also involve illicit drugs, household substances, or plant material.

- Self-injury: most commonly involves cutting. Other methods of self-injury include scratching, burning, hitting, pinching, head-banging, inserting sharp objects under the skin, and swallowing non-edible objects.

Those who self-harm without suicidal intent may do so for different reasons including to distract themselves from distressing feelings or thoughts, to release uncomfortable internal feelings of tension, to communicate emotional distress that might be difficult to put into words, to have a sense of being in control, or in an attempt to stop feeling numb.

Epidemiology

There are around 200,000 presentations to A&E for self-harm in the UK each year. .

Self-harm

In England, the proportion of people aged 16 to 74 years reporting ever self-harming is increasing. Approximately 1 in 4 females aged 16-24-year-old have reported self-harm at some point in their life according to the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey, although the number of higher in males.

Suicide

In 2022, 6,588 deaths were registered with a cause as suicide in the UK. The rates of suicide are three times more common in men than women. Regarding age, the risk of suicide is highest in those aged 45 and 54. Globally the most common methods of completed suicide are ingestion of pesticides, hanging, and firearms.

Aetiology & risk factors

The aetiology and risk factors for self-harm and suicide overlap but have some key differences (e.g. the suicide gender paradox).

The following table outlines some of the key risk factors including sex, age, mental health history, and life events amongst others.

History taking & risk assessment

Taking a history and performing a risk assessment are essential skills for any healthcare professional seeing patients presenting with self-harm.

People who have self-harmed may present in a variety of settings, but commonly they will be seen in the Emergency department (ED) or primary care. Below is a template that can

be used to address the important parts of gathering information from the individual after an incident of self-harm.

Gathering information

You can use an ABC model to structure your history taking and gather the important information. ABC stands for: Antecedent, Behaviour, Consequence

Antecedent (what happened before)

- Were there any triggers or precipitants to the episode of self-harm?

- Any current life stressors? Relationship difficulties? Recent arguments?

- Was the self-harm pre-planned or impulsive?

- If pre-planned

- What had they done?

- Had they researched methods of suicide?

- Had they sourced the materials needed for self-harm/suicide attempts in advance?

- Had they stockpiled tablets?

- Did they write a suicide note?

- Did they prepare or alter a will?

- Did they put their financial affairs in order (e.g., ceasing gas/electricity contracts)?

- Were precautions taken against being discovered?

- Did they wait until they were alone?

- Did they lock doors or hide themselves?

- Had they drunk alcohol or taken any recreational drugs beforehand?

Behaviour (what happened during)

- Where were they?

- Who were they with?

- Were they alone?

- What method of self-harm was used?

- If it was an overdose/self-poisoning;

- What did they take?

- How much did they take?

- What was the timing of the overdose – when did they take the tablets?

- Did they take them all in one go or was it a staggered overdose?

- What was going through their mind at the time of the act?

- What was their intention? Did they think that the act would end their life?

NOTE: Establishing the timing is important in certain overdoses (e.g. paracetamol) as it guides when you check plasma levels and aids decisions regarding management.

Consequence (what happened after)

- What did they do after self-harm?

- Did they try to seek or avoid help?

- Did someone find them?

- How did they get to A&E?

- How do they feel reflecting on the incident of self-harm now?

- Do they regret the self-harm?

- Do they regret the suicidal act not being successful?

- Do they have ongoing thoughts of self-harm or suicidal intent?

- If they were to go home;

- What is the likelihood of repeated self-harm?

- What might they do differently if they feel like this again in the future?

- How might they be able to keep themselves safe?

- Do they accept treatment and input from mental health teams?

- Are they future-orientated?

- Do they have future plans?

- Do they feel they have anything to live for (protective factors)?

- Do they feel hopeful or hopeless about the future?

Formal mental health history

The above questions as part of the ABC model can be incorporated into a full mental health history. A complete mental health history should cover:

- Previous episodes (e.g. methods of self-harm, frequency, any suicidal intent

- Psychiatric history (e.g. any known mental health disorder, any treatment in secondary care or by their GP)

- Medical history

- Family history (e.g. any attempted or completed suicide)

- Social history (e.g. living arrangements, home environment, support network, personal relationships, dependent children, recent stressful life events, occupation, financial concerns)

- Alcohol, smoking, and drug misuse.

Risk assessment

Following formal assessment, it is essential to clearly document a risk assessment to guide the management plan. Risk to self, risk from others, and risk to others should all be considered as part of a comprehensive risk assessment. The following are a list of important risk factors for self-harm and suicide:

- Individual factors

- Male

- Older age

- Family history of suicide

- Previous suicide attempt

- Severe depression

- Alcohol or opioid dependence

- Chronic physical health problems

- Feeling hopeless or a lack of protective factors

- Social factors

- Being widowed, separated, or single

- Being in an abusive relationship

- Living alone

- Bereavement

- Unemployment

- High-risk occupations (farmers, doctors)

- Access to means of self-harm (e.g., supply of medications or firearm)

- Factors related to the act

- Evidence of pre-planning (e.g. writing a will, writing a suicide note, researched suicide methods)

- Suicidal intent – the individual perceived the act to have high lethality

- Use of violent methods

- Precautions taken against being found

- Attempt discovered by chance

- Individual resists medical intervention

- Downplays seriousness of attempt

Management

The management of self-harm depends on its severity and place of presentation.

In this section, we discuss some of the overarching principles of managing a patient with self-harm, taking you through the initial management, what should be done once they are medically optimised, and then the ongoing care that often occurs in the community.

Initial management

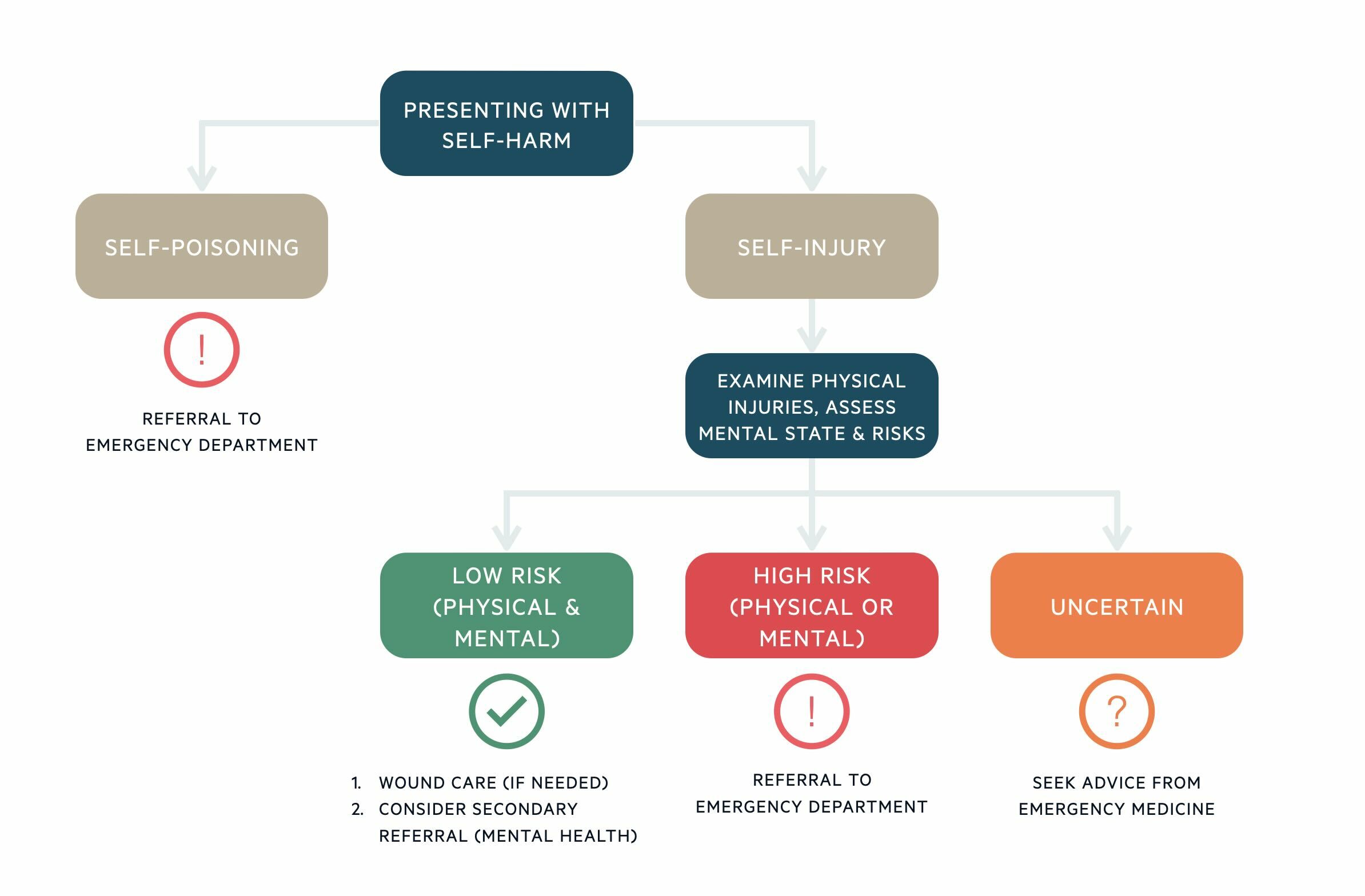

When an individual presents following an act of self-harm, immediate action must be taken. The NICE Guidelines [NG225] are summarised in the flow chart below:

If the individual has taken an overdose (self-poisoned), then they require urgent assessment and management in the Emergency Department (ED), regardless of the other risks. This is because it may be difficult to accurately determine how risky the overdose was without further investigations. TOXBASE provides useful advice for the management of self-poisoning with different substances.

If the individual has presented with self-injury, the physical injuries should be examined, and the mental state should be assessed. If either the physical injuries or mental state put the individual at high risk, they require urgent assessment and management in ED. If the severity of self-injury is minor and there are no immediate risks, the individual may be managed in primary care. This will include wound management as appropriate and consideration of referral to secondary mental health services.

If there is any uncertainty about the seriousness of the act of self-harm, advice should be sought from a consultant in Emergency Medicine. If a child or young person has self-harmed, they require referral to an ED with the appropriate expertise.

When arranging for an individual who has self-harmed to attend ED, consider arranging for them to be accompanied or transported there by ambulance, especially if there is a high risk of further self-harm or if the individual is reluctant to attend.

NOTE: Mental capacity refers to the ability of a person to decide on a specific issue at a time when it is needed. If an individual is deemed to lack capacity to consent to treatment following an act of self-harm, they may be treated under the Mental Capacity

Act in their best interests.

After medical optimisation

Often, once medically optimised, the individual will be reviewed by the Liaison Psychiatry team in ED for further mental state and risk assessment (e.g. risk of further self-harm/suicide, any safeguarding concerns).

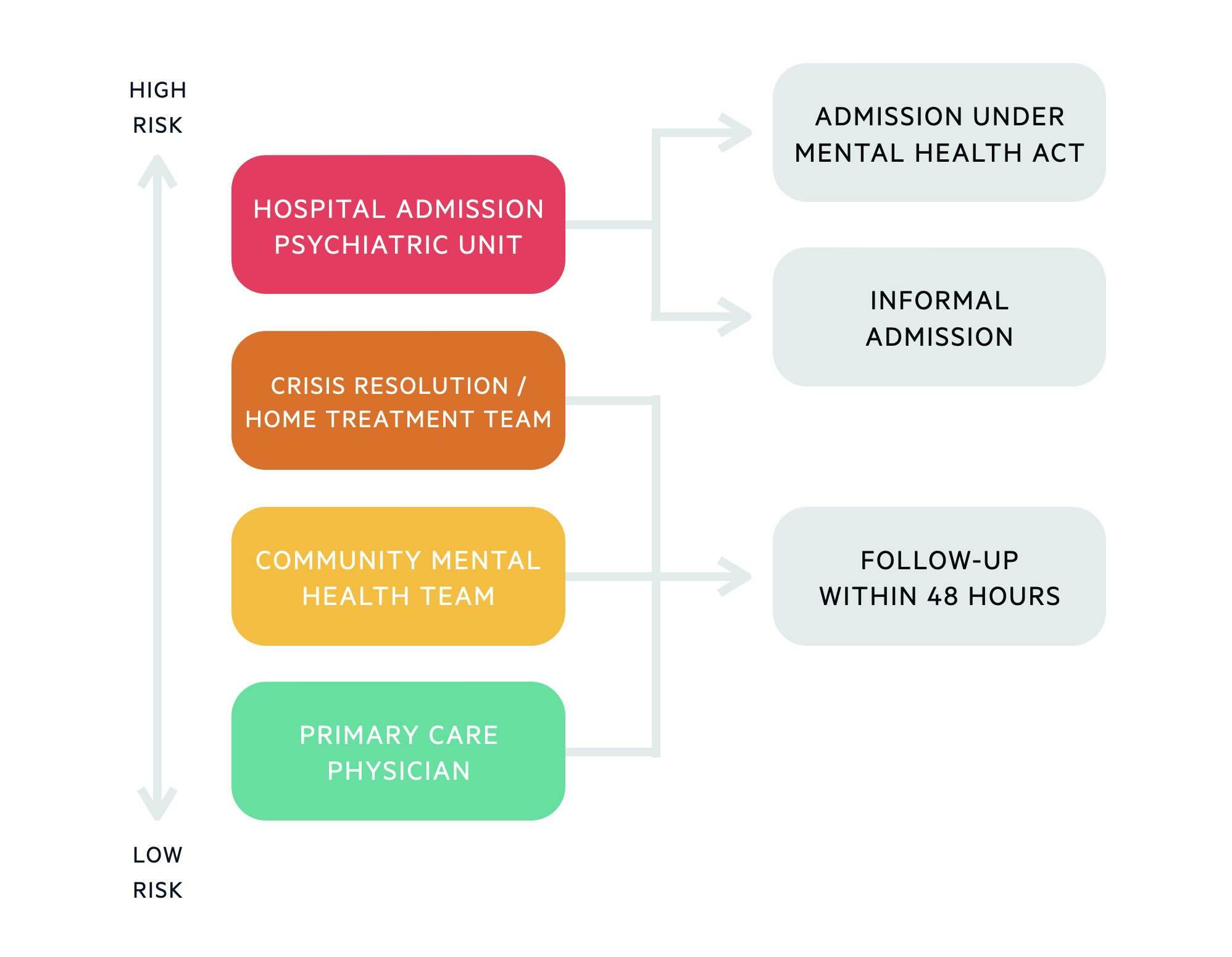

If the individual is deemed to be high risk, they may require admission to an acute psychiatric unit for inpatient management. If hospital admission is refused, the use of the Mental Health Act (MHA) may be deemed appropriate. The MHA allows compulsory admission of people who have a mental disorder of a nature and degree that warrants a period of assessment +/- treatment in the hospital. They require admission in the interests of their own health or safety, or for the protection of others. There are two important sections to know:

- Section 2: allows compulsory admission for up to 28 days for assessment (+/- treatment).

- Section 3: allows compulsory admission for up to 6 months for treatment.

An individual may consent to hospital admission, in which case they can have an informal admission as opposed to under section of the MHA.

Hospital admission is not the only option for those deemed to be high-risk. If the individual is motivated to engage with Services, ideally has social support and it is felt that risks can be managed in the community, they may be referred to a Crisis Resolution or Home Treatment Team.

Crisis teams offer more intense community support and monitoring, aiming to manage mental health crises in the home environment. They can visit the individual at home and review them regularly until risks have subsided. If the person is already known to a Community Mental Health Team, clinicians from this team may be best placed to provide follow-up.

Where secondary care services are not deemed necessary, the individual may be followed up in primary care by their GP. If discharged home, follow-up should be arranged within 48 hours of discharge from the hospital.

Community management

It may be possible to follow up and support the individual in primary care. In some circumstances, the GP may consider the need to refer to secondary care. The secondary care teams and reasons for onward referral are described below:

- Crisis Resolution Team / Home Treatment Team: If there is a significant escalation in risk of self-harm/suicide and they are deemed to need more intense support and monitoring.

- Community Mental Health Team:

- If the individual’s mental health disorder is deemed to need specialist management including psychological interventions or specialist medication reviews.

- If there is an increasing risk of self-harm.

- If there is evidence of cognitive impairment complicating the presentation, they may require a referral for further cognitive assessment.

- If there is a lack of adequate therapeutic response to management in primary care.

- Drug and Alcohol Services: If misuse of alcohol or drugs is present and exacerbates underlying mental health issues or increases the risk of self-harm.

There should be ongoing dynamic risk assessment to guide further management. The individual’s risk of self-harm and suicide needs to be reviewed regularly because these may change with time. It is important to reassess risk after each episode of self-harm because the risk associated with each episode may change significantly. The individual’s mental health, physical health, substance use and social circumstances should be kept under regular review in the community as this forms part of the risk assessment. The individual can be offered information about additional sources of support (e.g., the Samaritans, MIND).

Existing coping strategies should be reinforced, and the individual should be encouraged to develop alternative coping strategies to reduce or stop self-harm (e.g., relaxation and distraction techniques).

If stopping self-harm is unrealistic in the short term, harm minimisation techniques may be considered. These are less destructive or harmful methods of self-injury, as agreed among the MDT, and may include pinching, ice cubes, rubber bands, or using marker pens instead of sharp objects. Practical steps can also be taken to reduce self-harming behaviours (e.g. reducing access to means of self-harm). This might include removing self-harm items from the environment (e.g., sharps and items that might be used as a ligature), and careful prescribing/dispensing of drugs (e.g., providing the individual with a smaller quantity of medication they have to pick up more frequently, or prescribing medication that are safer in overdose).

An individual care plan may be developed between the individual and those involved in their care. Goals detailed in a care plan may include improving quality of life, reducing risk-taking behaviours, managing mental health problems, and improving social or occupational functioning. It is important for those who self-harm frequently to have a clearly documented crisis plan, that outlines self-management strategies, contact numbers, and information about what to do/who to contact in a crisis if self-management strategies are not helping. It is important to consider the needs of relatives and carers, as they may also be experiencing high levels of distress and anxiety.

Further reviews and follow-ups should be arranged as deemed necessary. Continuity of care should be a priority where possible. Individuals that don’t attend follow-up appointments need to be proactively followed up.

Prognosis

It is estimated that 1 in 6 people attending A&E, following an act of self-harm will self-harm again within a year.

Repeated self-harm is common, with 1 in 6 people attending A&E with self-harm repeating the act within a year. The relationship between suicide and self-harm is complex. Self-harm is overall associated with an elevated suicide risk, but many individuals engage in non-suicidal self-harming behaviours. For those who self-harm to release and manage emotions, self-harm may even be viewed as self-preservation.

It has been noted that whilst suicide may not be intended when a person begins to self-harm, suicidal intentions may develop over time. In those who self-harm, the risk of suicide is increased in those who are male, express suicidal intent, repeatedly self-harm, and have physical health problems.

Last updated: October 2024

References:

-

2014 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey

-

Suicidality in Borderline Personality Disorder - PMC (nih.gov)

-

TOXBASE

-

House of commons library. Suicide statistics

-

NHS Digital. Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014

-

Mind (www.mind.org.uk)

-

The Samaritans (www.samaritans.org)

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback