Epistaxis

Notes

Introduction

Epistaxis refers to bleeding from the blood vessels within the nasal mucosa.

Nosebleeds are common. The vast majority resolve spontaneously or with basic first aid. However, it remains a relatively common cause of presentation to A&E departments, with up to 6% of the UK population seeking medical attention due to epistaxis at some point in time.

On occasion, epistaxis requires intervention (e.g. nasal cautery or nasal packing) typically performed by an A&E or ENT doctor. In certain settings (discussed in more detail below), epistaxis should trigger an outpatient referral to ENT to exclude an underlying causative lesion (e.g. malignancy).

Aetiology

Bloods vessels in the nasal mucosa are delicate, superficial structures that are easily damaged.

The majority of cases are spontaneous without any clearly identifiable trigger. Trauma, often from picking one's nose, is a common cause.

- Trauma

- Inflammatory conditions

- Post-operative bleeding

- Tumours (both malignant and benign)

- Vascular malformations (hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia)

- Coagulopathy (e.g. thrombocytopenia)

- Mitral stenosis (raised venous pressure)

- Drug use (cocaine)

Anatomy

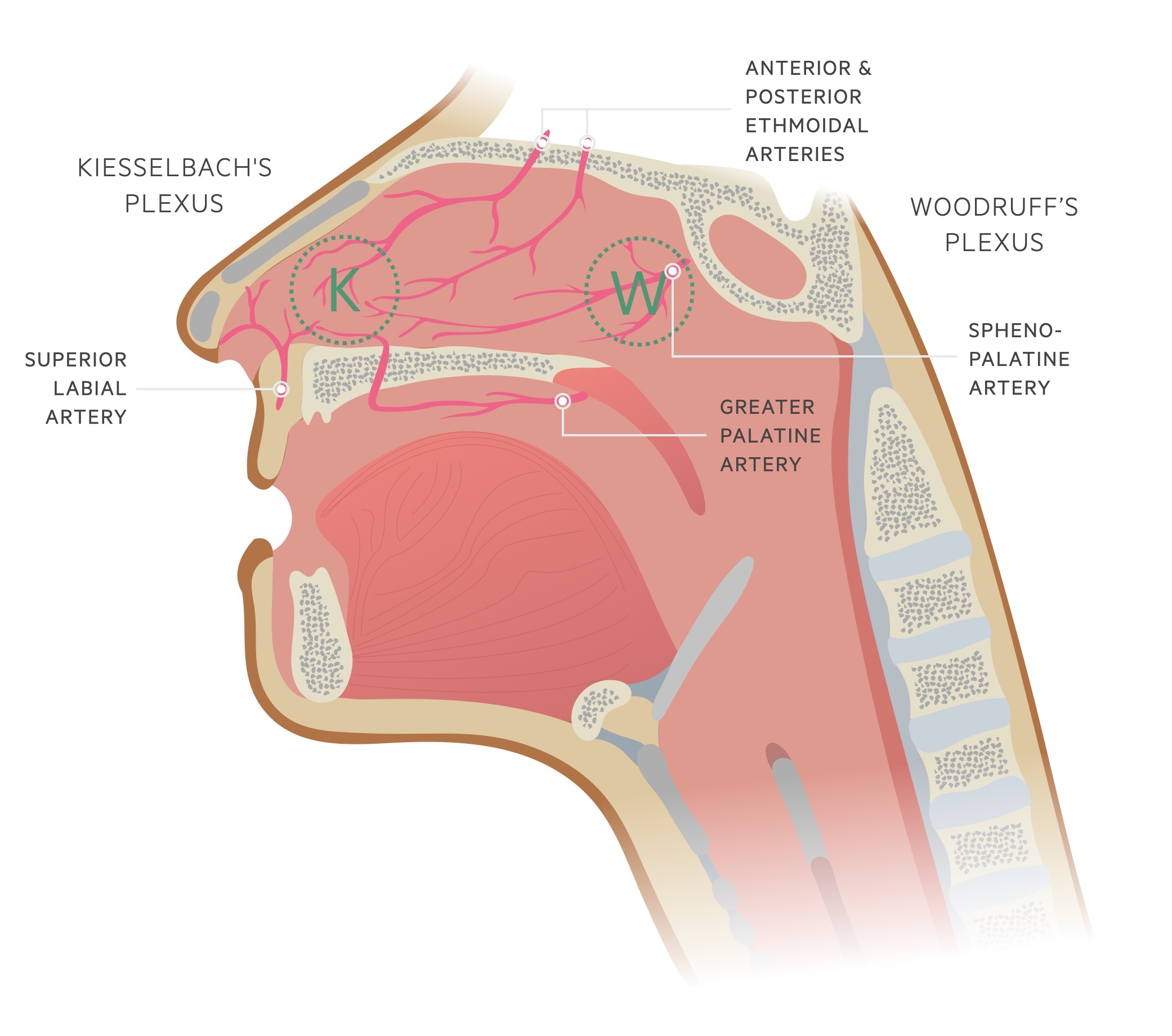

The nose is a highly vascular structure, receiving supply from both the internal and external carotid arteries.

The internal carotid artery supplies the nasal cavity via the ophthalmic artery and its branches the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries.

The external carotid artery supplies the nasal cavity via the maxillary artery and facial artery and their branches including the greater palatine artery, sphenopalatine artery, lateral nasal artery and superior labial artery.

In the majority of cases (up to 95%), bleeding originates from the Kiesselbach plexus of Little’s area. In a minority of cases, the bleeding arises in the posterior nasal cavity and is said to originate from Woodruff's plexus. These tend to bleed profusely and are more difficult to control.

Management

The majority of nosebleeds will settle with conservative management.

Note: If the patient is haemodynamically unstable a full ABCDE assessment and resuscitation should be initiated.

Initial management

Patients should be advised to sit leaning forward (ideally over a sink, which avoids swallowing or aspiration of blood) and to pinch the nasal nares (the soft part of the nose) for 10-20 minutes. If available, ice packs can be placed on the neck/forehead (resulting in vasoconstriction of supplying vessels) or ice cubes may be sucked. Patients should be encouraged to spit out any blood that accumulates in the mouth; remember that blood is an emetic and accumulation of blood in the stomach will cause nausea and vomiting.

If conservative measures fail to control bleeding, the patient should be referred to ENT (or an experienced A+E physician). At this point, it is advisable to obtain IV access and send bloods including an FBC, clotting screen (if on an anticoagulant or has liver disease or known coagulopathy) and group and save even in the haemodynamically stable patient.

In those receiving oral anticoagulants, reversal should be considered. This decision should be made with reference to the severity of the nosebleed and the indication for anticoagulation. Opinions from ENT and haematology may be sought.

Nasal cautery

Nasal cautery is commonly used as first-line therapy for those who fail conservative management. Prior to cautery, a topical local anaesthetic (ideally with a vasoconstrictor) should be administered. The bleeding point is then identified and cauterised using a silver nitrate stick.

Following cauterisation, a topical antibiotic such as Naseptin (avoid if allergies to neomycin, peanut, or soya) or Mupirocin may be prescribed.

Nasal packing

Packing should be avoided where possible as it mandates hospital admission for observation. Typically, it is reserved for when cautery is not available or fails.

Prior to packing, a topical local anaesthetic (ideally with a vasoconstrictor) should be administered. A number of ‘packs’ are available including the Rapid Rhino and nasal tampons. The pack should be secured externally and checked that it is not putting pressure on the nasal cartilage.

Patients with nasal packs should be admitted under the ENT surgeons. Packs tend to stay in for 24 hours. The advantage of inflatable packs (e.g. Rapid Rhino) is they can be deflated and observed - if bleeding restarts they can simply be reinflated. Analgesia should be prescribed and those with underlying respiratory conditions need close monitoring. Patients should be made NBM in case packing fails and surgical intervention is required.

The use of prophylactic IV, oral or topical antibiotics in those with nasal packs vary between different centres and local guidance should be followed.

Posterior bleeds

Posterior bleeds are somewhat more difficult to control. Double balloon catheters can be used to apply pressure to the posterior nasal cavity, where not available a foley catheter may be utilised. ENT advice and review should be sought.

Post-epistaxis advice

Most prescribe topical antibiotics in the form of Naseptin (avoid if allergies to neomycin, peanut, or soya) or Mupirocin. Those who have required packing may be given oral antibiotics.

After a nosebleed, patients should be advised to avoid the following for 24-48 hours:

- Hot drinks

- Blowing/picking nose

- Strenuous activity such as heavy lifting

- Lying flat

Referral

Refer patients to the relevant service if an underlying condition is suspected.

Younger than 2 years of age

Nosebleeds are uncommon in children under the age of two. These patients should be referred to a paediatric team. Always remember the possibility of non-accidental injury (NAI) - a possibility in all age groups.

Recurrent epistaxis

Clinical judgement, based on the presentation and patients personal and family history should be used to determine those who need further review.

A high index of suspicion is needed and conditions such as leukaemia should not be missed.

A number of high-risk groups exist (this list is not exhaustive):

- Previous occupational exposure (e.g. wood dusts, chemicals)

- Family history or signs suggestive of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia

- Signs of cancer (e.g. persistent lymphadenopathy, hearing loss, anosmia, hearing loss, visual changes)

- Older patients (increasing incidence of head and neck cancers with age)

- Chinese ethnicity (higher incidence of nasopharyngeal cancer)

- Males aged 12-20 (possibility of angiofibroma)

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback