Acute pancreatitis

Notes

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis refers to an acute inflammatory process involving the pancreas.

Pancreatitis occurs due to the uncontrolled release of activated pancreatic enzymes within the pancreas resulting in autodigestion. Patients may suffer a spectrum of disease from mild abdominal discomfort to multi-organ failure.

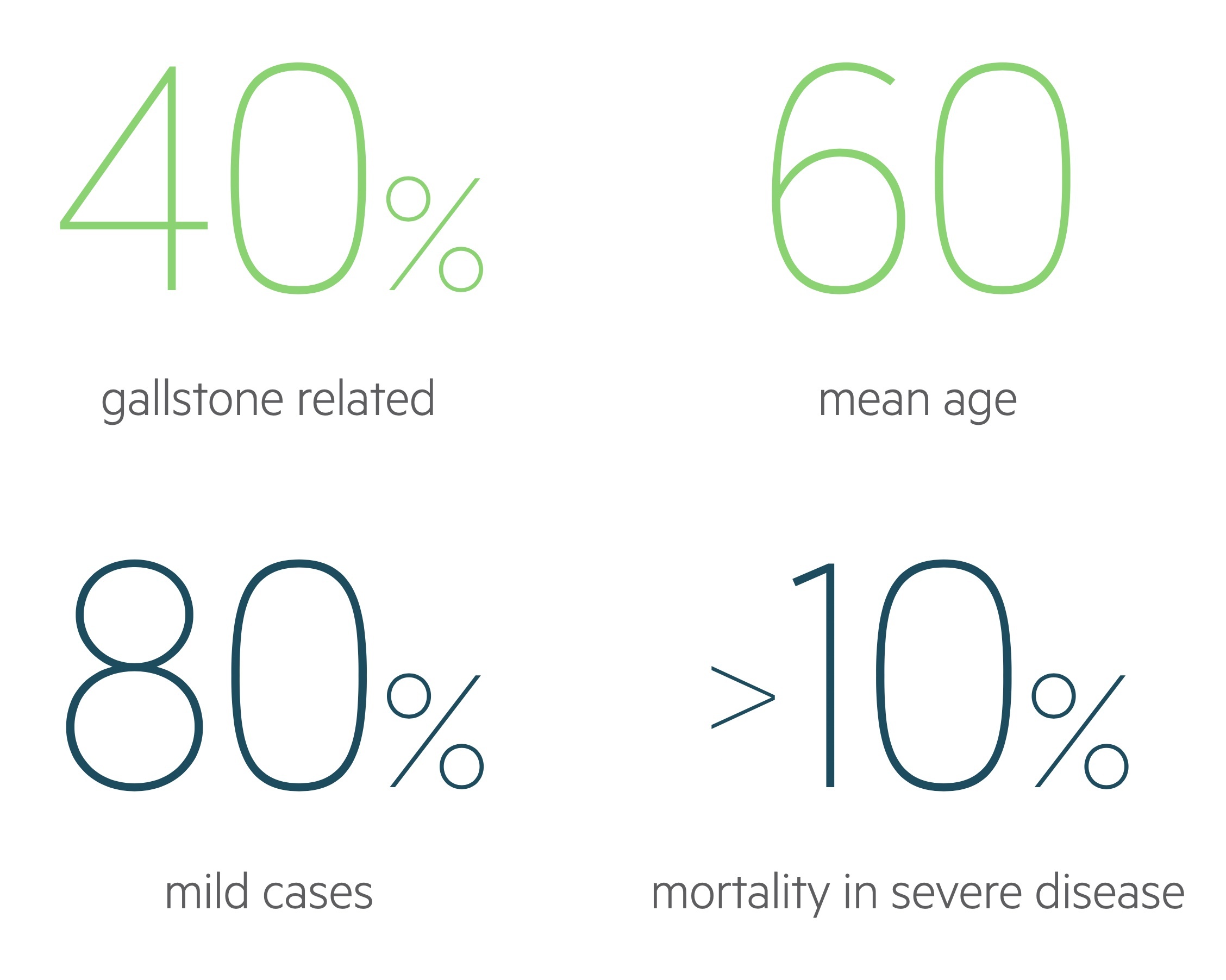

Pancreatitis has an annual incidence of 13-45 cases per 100,000, with trends showing that it is becoming more common. It tends to occur more in men and is commonly secondary to gallstones or alcohol misuse.

Aetiology

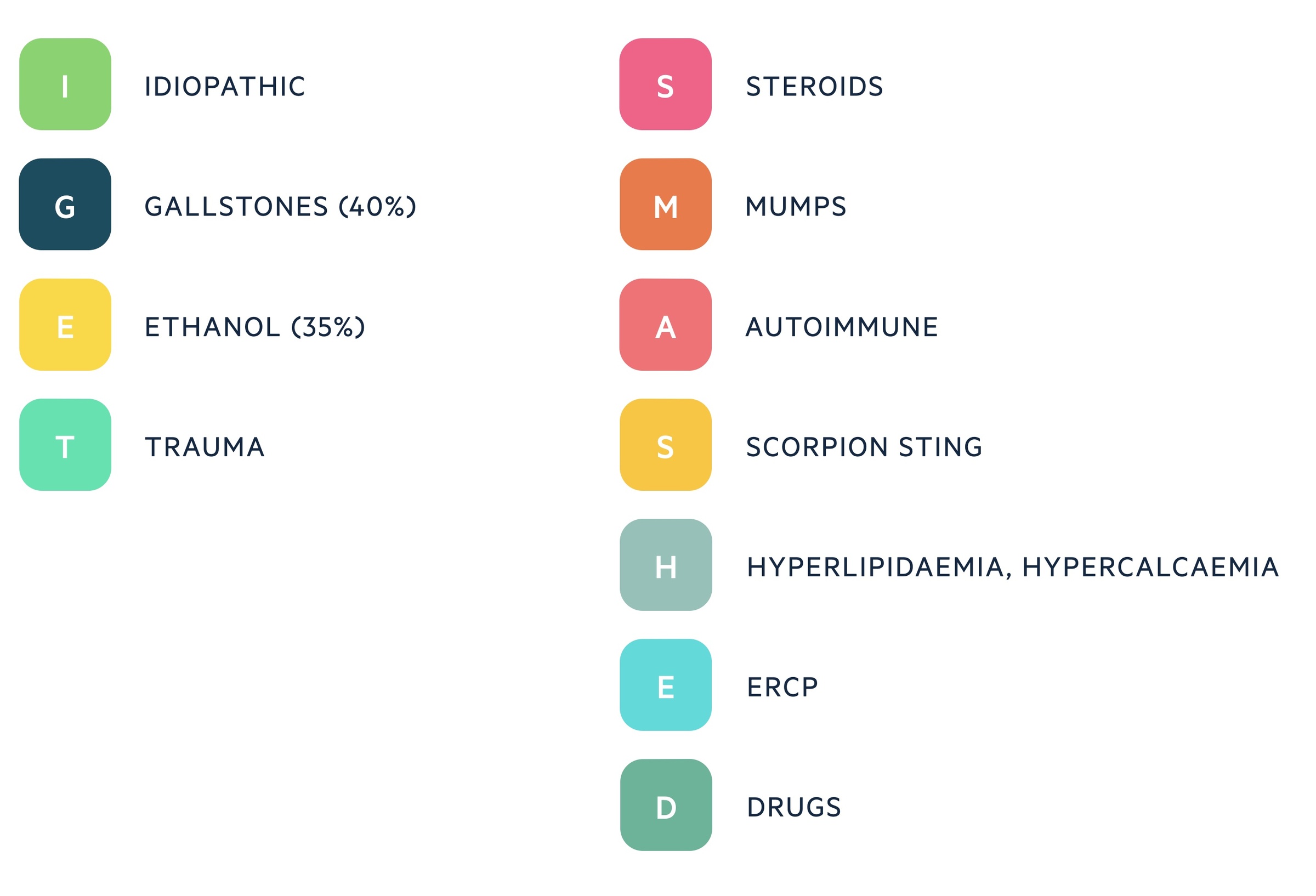

Alcohol misuse and gallstones are the most common causes of acute pancreatitis.

Alcohol misuse and gallstones are responsible for upwards of 75% of cases of acute pancreatitis. Other important causes include ERCP and hyperlipidaemia (e.g. hypertriglyceridaemia).

The causes of acute pancreatitis may be remembered with the mnemonic I GET SMASHED.

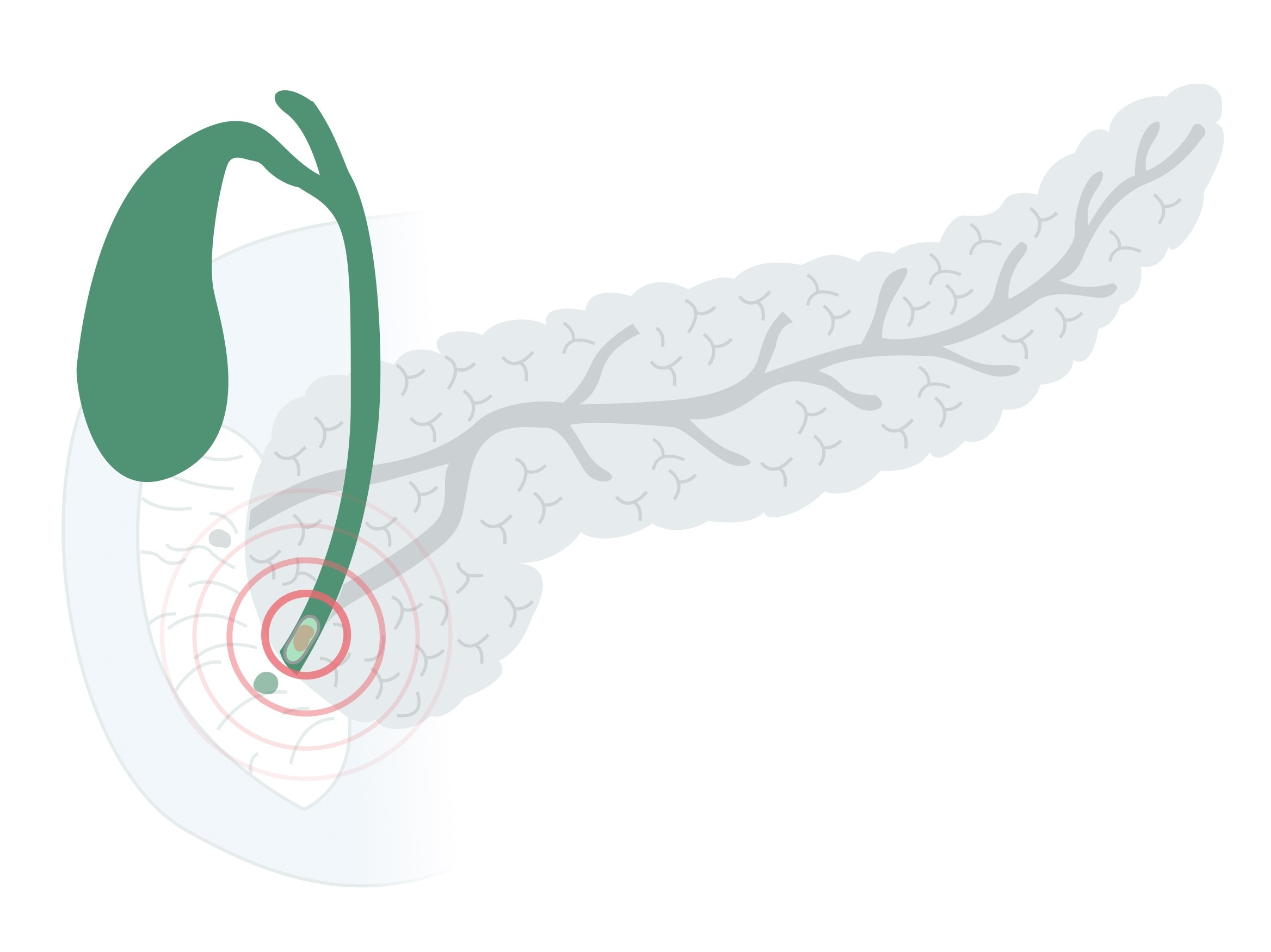

Gallstones

Gallstones are the most common cause of acute pancreatitis, they are responsible for around 40-50% of cases. Gallstones migrate from the gallbladder to the biliary tree where they may cause obstruction of the ampulla. It is thought that biliary reflux and raised pressures are responsible for the resultant pancreatitis.

Alcohol

Alcohol has toxic effects on the pancreas and is implicated in around 25-35% of cases. Though it is known to increase the production of digestive enzymes, the exact mechanism by which it causes pancreatitis remains unclear.

Alcohol commonly causes chronic pancreatitis with alcoholics suffering acute-on-chronic attacks. It may also induce acute pancreatitis without pre-existing disease following a significant binge.

Other

Acute pancreatitis is a significant complication in those undergoing an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). It is estimated 1-3% develop the condition following the procedure.

Operations in which the pancreas is handled or mobilised may result in pancreatitis. Infections, trauma, drugs, hyperlipidaemia, hypercalcaemia and hypothermia may all result in acute pancreatitis.

A proportion of cases are idiopathic. It is thought the majority of these occur secondary to unidentified biliary disease.

Pathophysiology

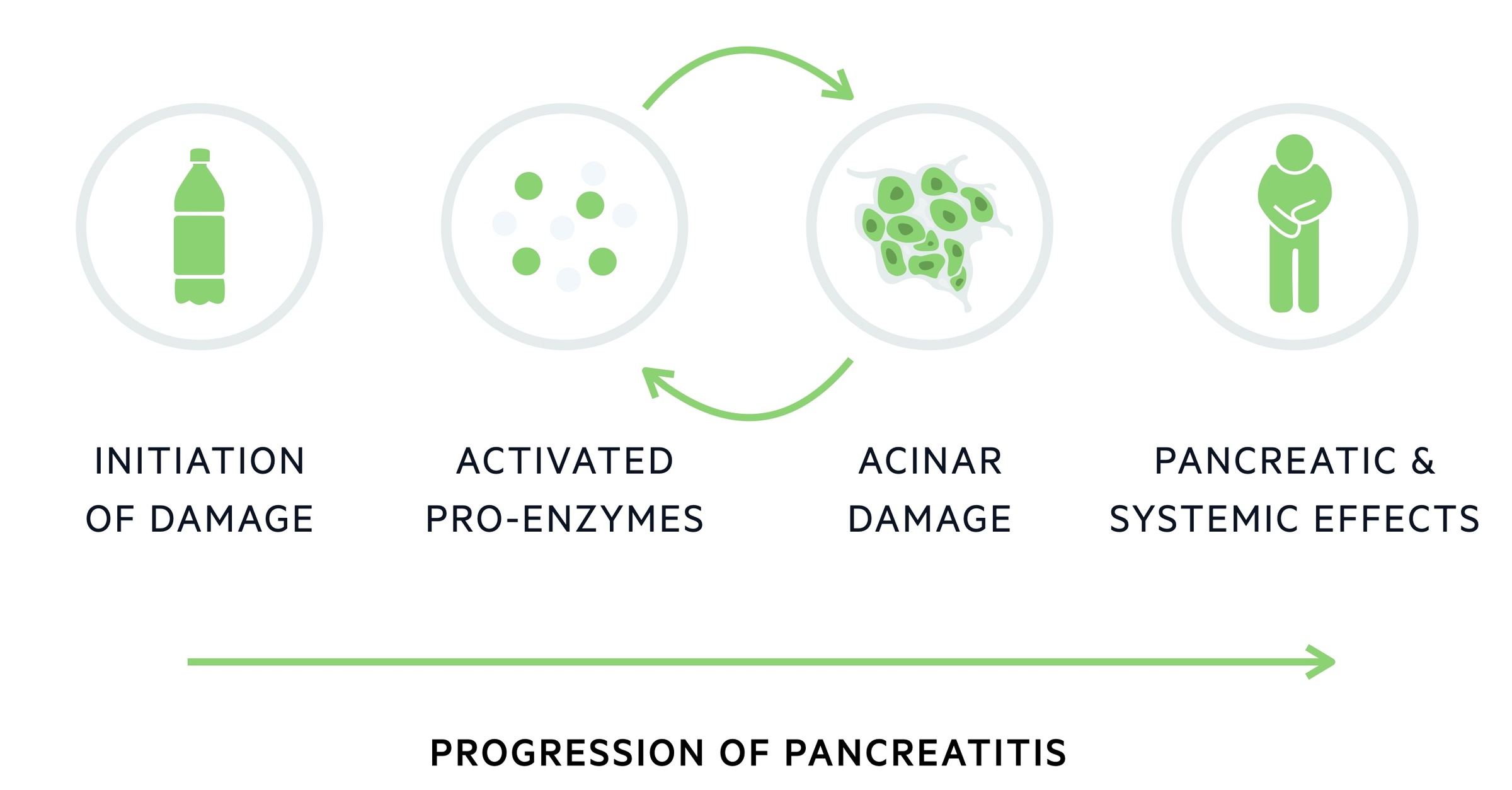

Pancreatitis is caused by the abnormal release and activation of enzymes, which cause autodigestion of pancreatic tissue.

The pancreas has both endocrine and exocrine functions. Endocrine function is governed by the islets of Langerhans and the hormones produced include insulin and glucagon.

The pancreatic ductal cells are responsible for the exocrine function. They produce the ‘pancreatic juice’ composed of bicarbonate and digestive enzymes. One of these enzymes, trypsin (helps with the breakdown and digestion of proteins), is key to the development of pancreatitis.

Under normal circumstances, the pancreas releases zymogens - inactive enzyme precursors (trypsinogen in the case of trypsin). In pancreatitis, normal zymogen transport fails and trypsinogen is converted to trypsin within the pancreas leading to a cascade of zymogen activation. This triggers the recruitment of inflammatory cells and the release of inflammatory mediators.

This inflammation causes changes in the vascular bed, leading to increased permeability and resultant oedema. The condition may be worsened by the release of inflammatory mediators and enzymes into the systemic circulation. This can result in a systemic inflammatory response (SIRS), sepsis and adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Clinical features

The presentation of pancreatitis may range from mild abdominal pain to life-threatening shock.

Abdominal pain is the most common presenting symptom. It tends to be epigastric with a relatively sudden, severe onset and typically associated with vomiting. It continues as an ache of variable severity, may be worsened on movement and commonly radiates to the back.

Signs of a systemic inflammatory response are common and include pyrexia (fever) and tachycardia. Vomiting and 'third spacing of fluid (where fluid exits the vascular space into the tissues, here due to inflammation) can result in a significant fluid deficit and as such patients may have dry mucous membranes and reduced urinary output.

Symptoms

- Abdominal pain (may radiate to the back)

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Anorexia

- Diarrhoea

Signs

- Abdominal tenderness

- Abdominal distention

- Tachycardia

- Tachypnea

- Pyrexia

Eponymous signs

Though a favourite of examiners, these signs are rarely seen in practice. They represent internal bleeding and can be seen as a relatively late sign in severe haemorrhagic pancreatitis:

- Cullen’s sign: peri-umbilical bruising (first described in ruptured ectopic pregnancy)

- Grey-Turner’s sign: flank bruising

Investigations & diagnosis

A serum amylase elevated 3 times above the reference range is considered diagnostic.

Amylase & lipase

Amylase is a digestive enzyme produced by the pancreas and salivary glands. It plays a role in the breakdown of carbohydrates. A patient with clinical features consistent with acute pancreatitis and an elevated amylase (3 times above the reference range) can be considered as very likely to have the condition.

Levels rise acutely before falling after 3 days (urinary amylase may remain elevated for a longer period). Patients who present late may therefore have a ‘missed peak’. It should be noted that even in severe pancreatitis the amylase may be normal, particularly in those with acute-on-chronic disease. In these cases, a CT abdomen and pelvis is generally needed to confirm the diagnosis and exclude alternative causes.

Aside from pancreatitis, there are a number of causes of elevated amylase. These include parotitis, bowel obstruction, intestinal inflammation, trauma, numerous malignancies and ruptured ectopic pregnancies - however, levels tend to only be mildly elevated.

Some centres prefer to use serum lipase. Again, levels elevated 3 times above the reference range are indicative of pancreatitis. Lipase has a longer half-life and as such levels remain elevated longer than amylase. Raised levels are also more specific for pancreatic disease than amylase.

Bedside

- Observations

- ECG

- Blood sugar

- Pregnancy test

Bloods

- Amylase/lipase

- FBC

- U&Es

- CRP

- LFTs (assess for any evidence of concomitant cholangitis)

- Bone profile (hypocalcaemia is common, used in scoring)

- LDH (used in scoring)

- Serum glucose (particularly important in diabetics where blood glucose control often worsens, also used in scoring)

- Lipids (hyperlipidaemia is a cause of pancreatitis)

- Arterial blood gas (assess oxygenation and acid-base, pO2 is also used for scoring acute pancreatitis)

Imaging

Ultrasound: used to demonstrate gallstones or a dilated common bile duct. The pancreas may be visualised.

Computed tomography: used to confirm diagnosis when uncertainty remains and to exclude complications of disease.

MRCP: most commonly indicated in suspected gallstone pancreatitis to help evaluate for CBD stones.

Glasgow score

The Glasgow score, completed in the first 48hrs, helps to assess the severity of acute pancreatitis.

A score of 3 or greater indicates severe pancreatitis, these patients have a high mortality and should receive HDU/ITU review. It is normally completed at admission and repeated at 48 hours.

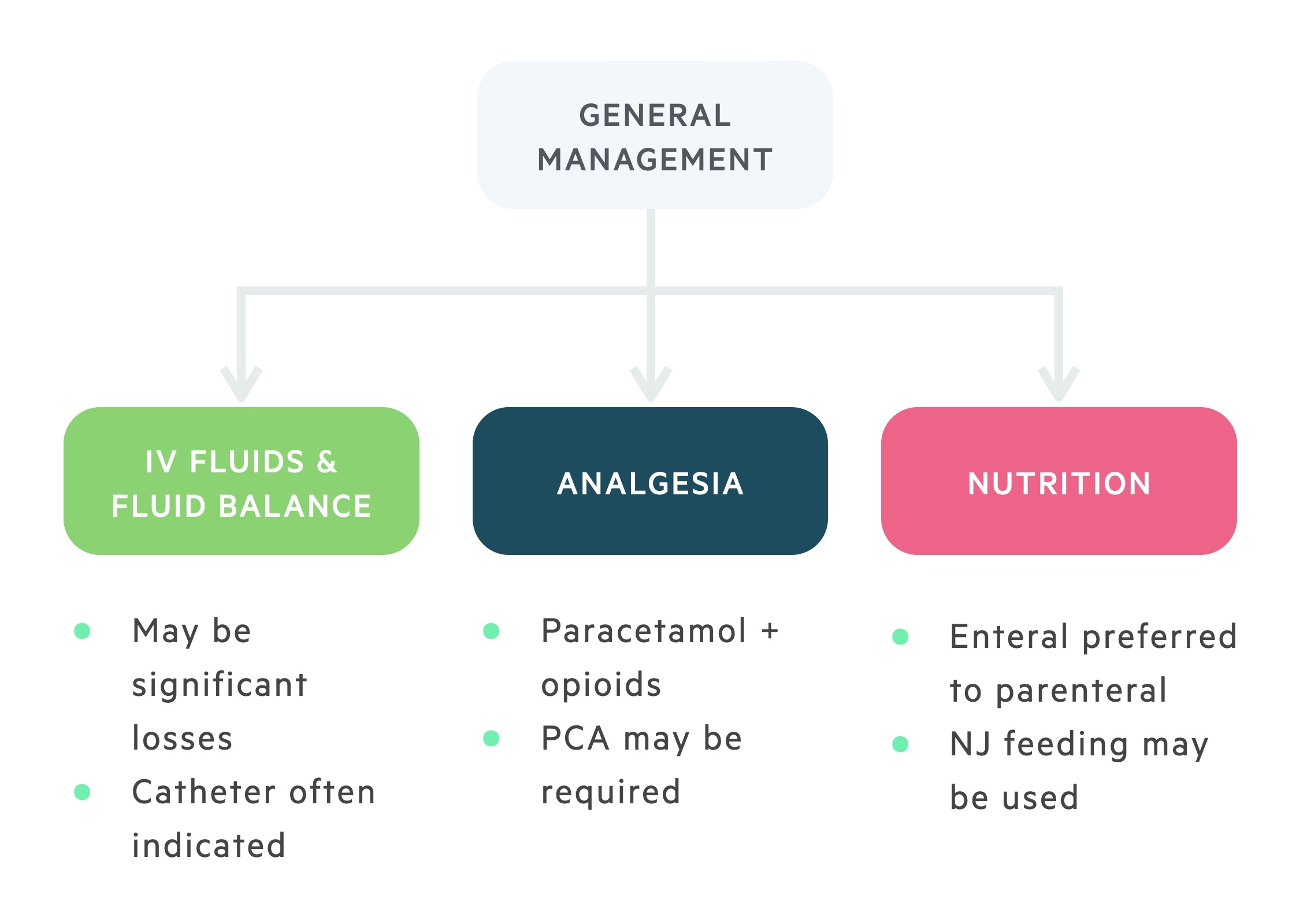

General management

General management consists of analgesia, appropriate fluids and nutritional support.

The majority of cases of acute pancreatitis are treated with supportive measures. This normally includes:

- IV fluids

- Analgesia

- Nutritional support

Most patients will be managed by the general surgeons though some hospitals have pathways that send patients to gastroenterology (in particular those with pancreatitis secondary to alcohol excess). In more severe cases organ support may be needed for systemic complications with HDU/ITU care indicated. In these severe cases, and patients who may require intervention, transfer to a tertiary hepatobiliary department should be considered.

The Glasgow score (see above) can help to identify patients that need critical care input, though clinician judgement must be used. Even if the patient doesn’t need admission to HDU/ITU immediately, it is good practice to involve the intensivists early on in those that may deteriorate.

Supportive

Pain is the most common complaint and patients should receive adequate analgesia. Morphine can be used, but may lead to spasm of the sphincter of Oddi. Pethidine and buprenorphine are alternatives.

Patients require fluid resuscitation to compensate for third-space losses. They may need aggressive intravenous fluids, particularly in the first 24 hours. A careful fluid balance should be recorded and a urinary catheter is indicated in all but the mildest cases.

Nutrition

Our understanding of how to best manage nutrition in patients with acute pancreatitis continues to evolve. In mild cases, a low-fat diet may be reintroduced once tolerated by the patient (i.e. the pain has settled and they have an appetite).

In patients with severe disease where a normal diet is not tolerated other options must be explored. As a general rule enteral feeding is preferred to total parenteral nutrition (TPN). It is thought enteral feeding helps maintain the mucosa and prevents translocation of bacteria. Nasojejunal feeding is commonly used.

TPN should be used in patients with ileus or where nutritional requirements are not being met.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not routinely indicated in acute pancreatitis and they should not be used prophylactically. Antibiotics should be commenced in patients with suspected/confirmed infected pancreatic necrosis, cholangitis or another infective source.

Gallstone pancreatitis

Patients with gallstone pancreatitis need supportive management, biliary decompression where indicated and cholecystectomy when appropriate.

Diagnosis

Following a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis an USS is indicated in essentially all patients (may be omitted in those with an admission CT that is considered conclusive).

In those with signs or blood tests indicative of an obstructed biliary system, or an inconclusive USS, an MRCP will normally be arranged to assess for CBD stones.

General management

The general management is as described above. Appropriate IV fluids, analgesia and nutritional support are key.

Antibiotics should be commenced in any patient with suspected cholangitis or other infective source.

ERCP

In patients with gallstone pancreatitis, CBD stones and cholangitis urgent decompression is required. ERCP should also be promptly organised for those with stones obstructing the CBD. This can be achieved with ERCP and stone extraction (+/- sphincterotomy, +/- stent).

Cholecystectomy

Cholecystectomy is recommended following recovery from gallstone pancreatitis. Ideally, in cases that are relatively mild, this can be completed during the index admission.

In other patients, with more severe disease, a longer delay may be indicated and repeat CT scans may be sought pre-operatively.

It is key that any biliary stones or obstruction are diagnosed pre-operatively. Patients generally have MRCP if there is any suspicion.

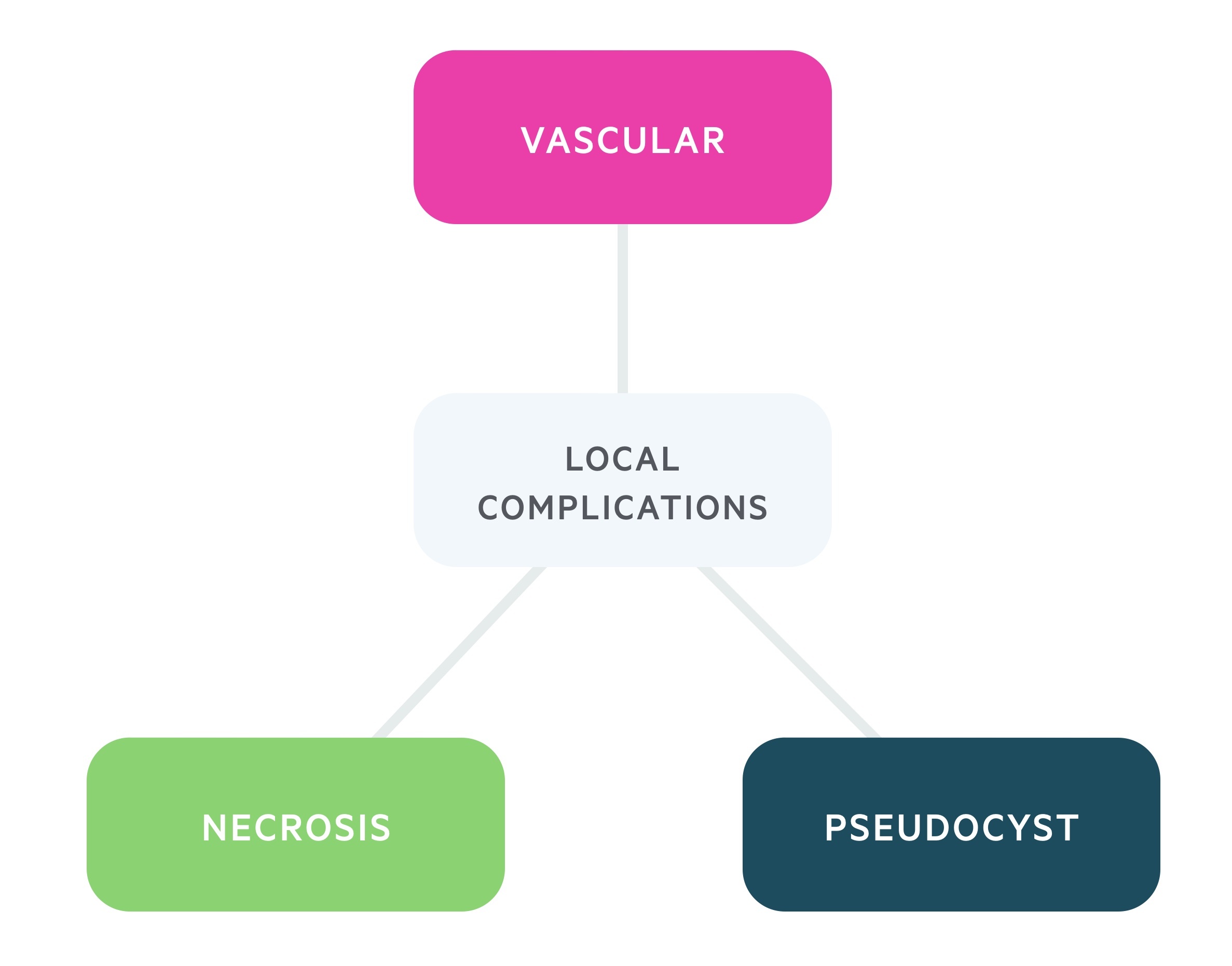

Local complications

Local complications of acute pancreatitis include pancreatic necrosis and pancreatic pseudocyst formation.

Pancreatic necrosis

In certain cases, continued inflammation leads to localised thrombosis, haemorrhage and necrosis within the pancreas. Though initially sterile, there is a 30-70% chance of infection. This is a major cause of mortality in those with acute pancreatitis.

Patients with suspected infected necrosis should have a CT guided fine needle aspiration and culture. Culture positive patients are generally managed with appropriate antibiotics guided by microbiology. Drainage or surgical debridement may be required.

Pancreatic pseudocyst

These are organised peripancreatic collections of pancreatic fluid, normally defined as being present for four or more weeks after an acute episode. The term 'pseudo' reflects the absence of an epithelial lining around the cyst, instead being surrounded by fibrotic granulation tissue.

If small and asymptomatic these can be monitored, but they frequently cause pain and the feeling of fullness. In addition, they can be complicated by rupture, haemorrhage or cause bowel/gastric outlet obstruction. Pseudocysts that are symptomatic or large require endoscopic, radiological or surgical management.

Vascular complications

The inflammatory process that characterises acute pancreatitis may have significant effects on neighbouring vasculature:

- Pseudoaneurysm: these are rare but when they occur life-threatening haemorrhages may result. It can affect any local vessel but it is often seen in the splenic and hepatic arteries. They normally occur in association with pancreatic pseudocysts. When haemorrhage occurs, interventional radiology intervention is normally the mainstay of management after appropriate resuscitation.

- Venous thrombosis: a relatively common and likely under recognised complication, venous thrombosis may affect the portal, splenic and superior mesenteric veins. It is often diagnosed incidentally on repeat CT in patients with severe pancreatitis. Optimal management of the underlying pancreatitis is key, anticoagulation decisions should be made following discussion between surgeons and haematology.

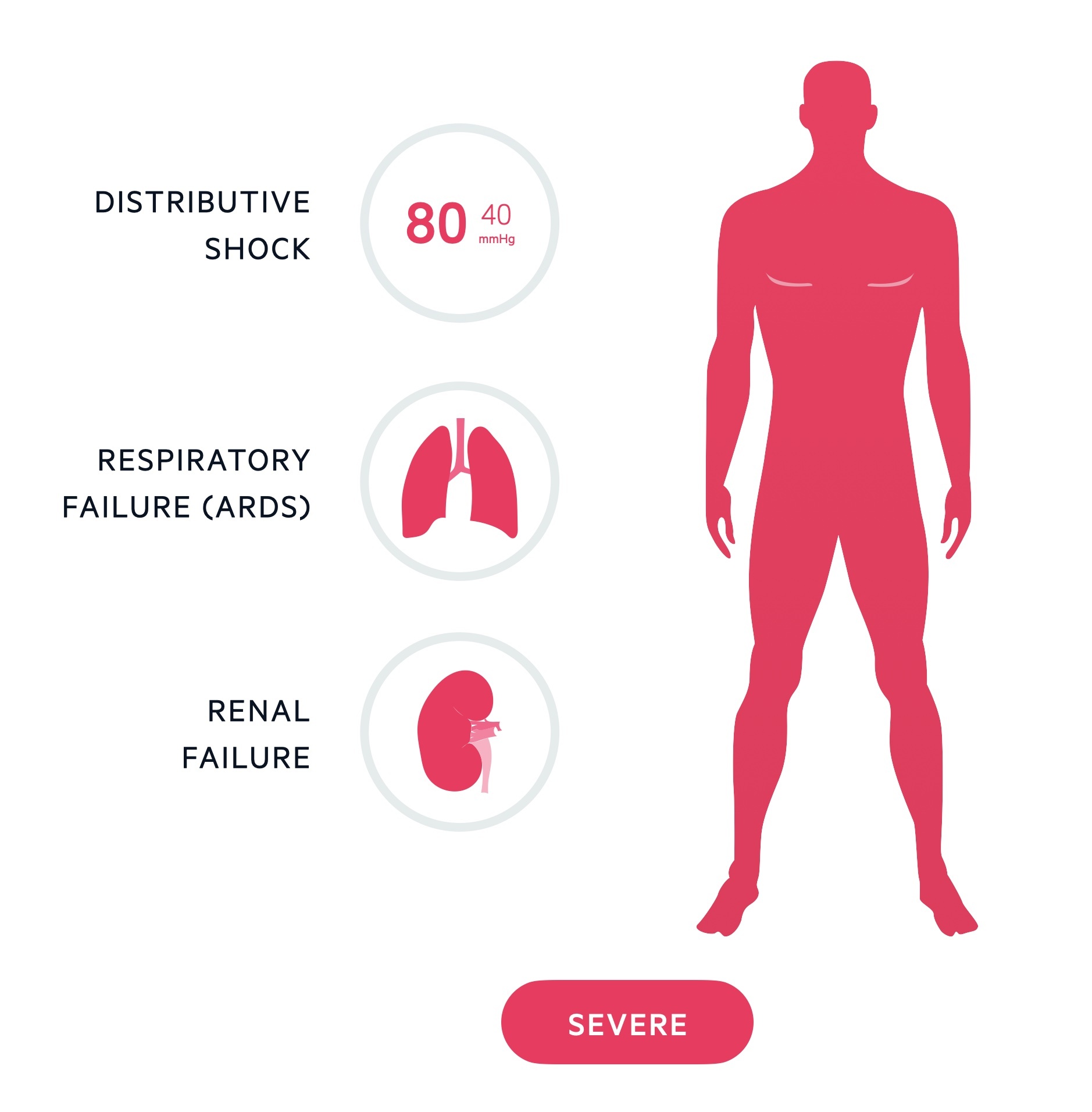

Systemic complications

Severe acute pancreatitis can result in ARDS, renal failure and distributive shock.

As discussed above, the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis represents a broad spectrum of severity. Mild cases may not even require hospitalisation, whilst severe cases are life-threatening. A lot of this depends on the severity of the systemic inflammatory response.

In some individuals a cascade of inflammatory mediators leads to systemic complications including:

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Renal failure

- Shock (multifactorial but often distributive in nature)

In those with single or multiple organ failure mortality is greatly increased. These patients need HDU/ITU care with organ support and close monitoring.

Prognosis

The prognosis of pancreatitis is highly dependent on the severity and complications that can occur.

The overall mortality of pancreatitis is estimated at 3-5%. However, severe acute pancreatitis may be associated with a mortality of 20-40%.

Last updated: October 2024

References:

-

Metri, A. Et al. Predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis: Current approaches and future directions. Surgery Open Science. Volume 19, June 2024, Pages 109-117

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback