Anal fissure

Notes

Overview

An anal fissure refers to a tear in the lining of the anus or anal canal.

An anal fissure is one of the most common anorectal disorders that refers to a tear in the lining of the anal canal. This classically leads to pain, particularly on defaecation, and can lead to PR bleeding. They may be acute or chronic:

- Acute: present for < 6 weeks

- Chronic: present for > 6 weeks

Anal fissures are common with a peak incidence between 15-40 years old, although they can occur at any age and have an equal sex prevalence.

Aetiology

Anal fissures are most commonly due to local trauma from conditions such as constipation, diarrhoea, or anal sex.

Anal fissures may be broadly divided into primary or secondary:

- Primary: no clear underlying cause

- Secondary: associated with underlying cause (e.g. constipation, inflammatory bowel disease)

Primary fissures

In primary anal fissures, there is no obvious underlying cause. Factors thought to be associated with the development of fissures include an increase in internal anal sphincter tone that affects blood flow leading to local ischaemia and increased risk of tearing. In addition, there is thought to be a lack of nitric oxide synthase that is needed to generate nitric oxide that helps sphincter relaxation.

Secondary fissures

In secondary anal fissures, there is an identifiable underlying cause of the tear in the anal canal. These include:

- Constipation: passage of hard stool can tear the anal canal

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Malignancy (e.g. squamous cell anal cancer)

- Sexually transmitted infections (e.g. HIV, syphilis)

- Infections (e.g. bacteria, fungal, viral)

- Anal trauma (e.g. anal sex)

- Pregnancy and childbirth

Pathophysiology

The majority of anal fissures occur on the posterior midline of the anal canal.

Anal fissures are typically located within the anoderm. This describes the epithelium located distal to the dentate line for approximately 1.5 cm. It is covered in squamous epithelium that is highly innervated leading to pain.

Once a tear develops it can lead to a revolving cycle of pain and bleeding with up to 40% of fissures becoming chronic. Occasionally, the tear can lead to exposure of some of the internal sphincter fibres leading to spasm that increases pain and worsens healing.

The most common location is the posterior midline, which has much less blood flow compared to other areas of the anal canal. Fissures occurring in childbirth are commonly located anteriorly.

Clinical features

Pain on defaecation and PR bleeding are the two most common symptoms of an anal fissure.

The pain associated with an anal fissure is typically a severe sharp pain, which occurs during defaecation. This is followed by a deep burning pain that may last for hours.

Symptoms

- Anal pain: usually a severe sharp pain on defaecation

- Bleeding: usually mild. Blood is bright red and seen on wiping or on the stool

- Crying during defaecation: a typical feature in a child with an anal fissure

Signs

Examination of an anal fissure can be extremely painful, especially during a digital rectal examination. Therefore, this part of the examination may be ignored to prevent causing the patient significant discomfort.

- Tear: spread the gluteal cheeks gently to try and visualise the tear. Not appreciable in all patients.

- Acute tear: seen as a fresh, superficial laceration akin to a paper cut

- Chronic tear: seen to have raised edges with/without white fibres of the internal anal sphincter at the base

- Skin tags (soft, skin-coloured growth): commonly associated with chronic fissures

If the fissure is unable to be visualised, it may be suggested by applying gentle digital pressure to the posterior (or anterior) midline of the anal verge (i.e. where the fissure is suspected). If this reproduces the patients' pain then it suggests a fissure.

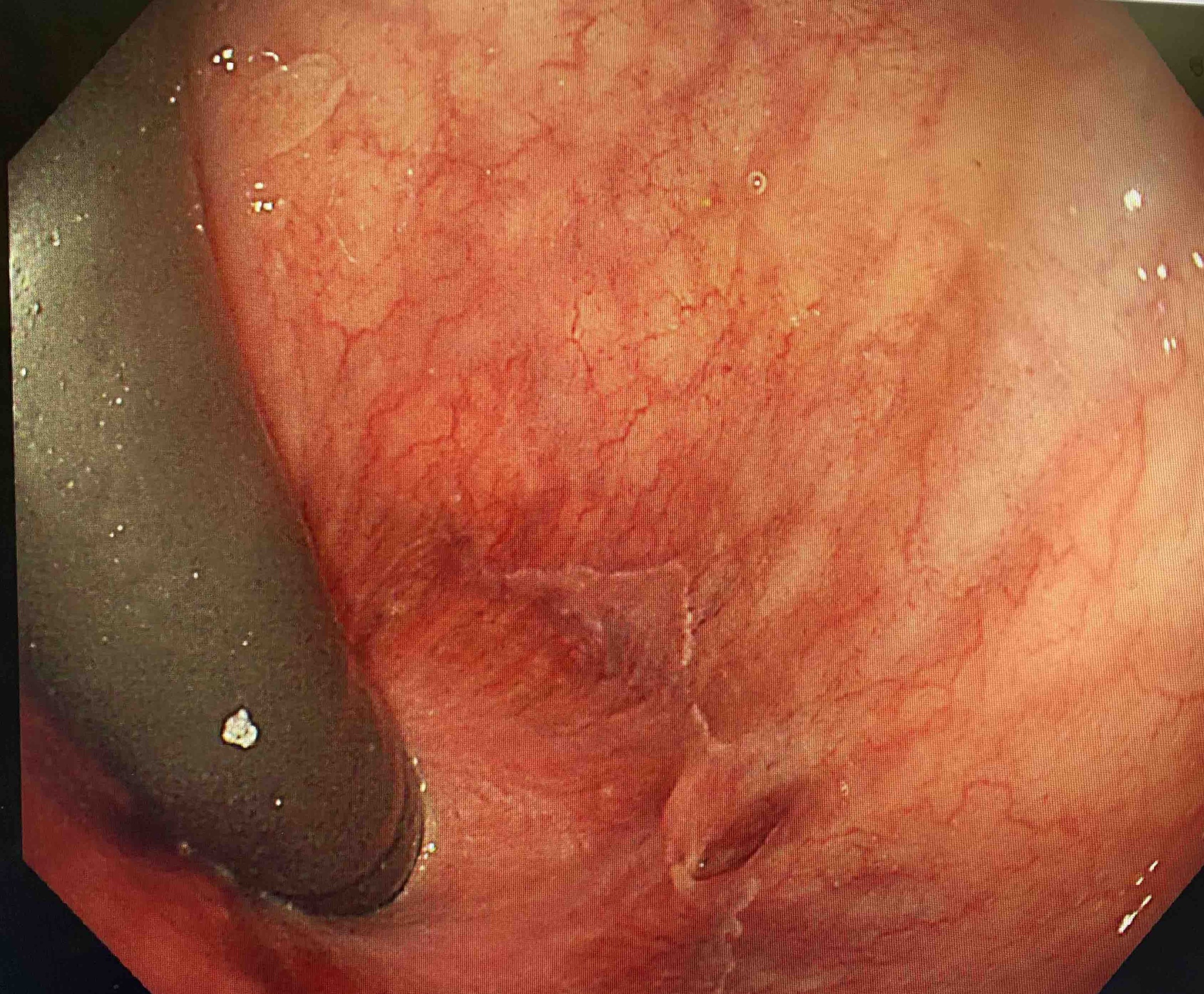

Anal fissure seen at flexible sigmoidoscopy

Retroflexion in the rectum during flexible sigmoidoscopy

Diagnosis & investigations

An anal fissure is usually a clinical diagnosis that can be confirmed with direct visualisation.

The diagnosis of an anal fissure is based on the history of severe pain during defaecation that may last for hours afterward. It can be confirmed with direct visualisation of the fissure on clinical examination, but this is not always possible and is not required for the diagnosis.

It is important to consider alternative causes for the patients' presentation, particularly thinking about dual pathology (e.g. an anal fissure and Crohn’s disease). The differential can include:

- Haemorrhoids

- Perianal ulcers (e.g. due to inflammatory bowel disease or sexually transmitted infections)

- Fistulae

- Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: an uncommon condition seen in patients with straining, rectal prolapse, or rectal intussusception. There may be one or multiple ulcers in the rectum, usually observed during endoscopy.

- Perianal abscess

Remember, anal fissures are uncommon in the elderly. Perianal pain and bleeding in this group should lead to a low threshold for investigation of malignancy.

Management

It is important to provide topical agents and ensure the stool is soft and easily passes.

Constipation is a common factor in the development of anal fissures. It can also exacerbate the pain of an anal fissure due to straining and passage of hard stool. Therefore, in all patients, it is important to recommend increasing dietary fibre, water intake, and eating a balanced diet.

Acute anal fissures

Patients should be offered lifestyle advice, analgesia, and topical agents as necessary:

- Lifestyle advice: ensure stools are soft and easy to pass (increase fibre, water, etc).

- Analgesia: advise paracetamol with or without NSAIDs (unless contraindicated). Avoid opioids as can cause constipation. Sitting in shallow, warm baths can help with the pain.

- Topical agents: a short course of lidocaine 5% ointment can be applied before passing stool (few days only). Rectal glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) 0.4% ointment may be applied twice a day for 6-8 weeks to aid healing by reducing anal sphincter pressure and spasm.

If there is a suspected secondary cause of anal fissure, it is important to treat the underlying cause or refer to the appropriate specialty.

Chronic anal fissures

In general, the management of chronic (i.e. non-healing) anal fissures depends on the age of the patient.

- Children: seek advice or refer to a paediatrician if not healing by 2 weeks (earlier if the child in a lot of pain)

- Adults: if still symptomatic check adherence, consider alternative medications (e.g. diltiazem cream), and referral to colorectal surgeons. If asymptomatic, but unhealed, consider a second course of GTN ointment or referral to the colorectal surgeons

Anal fissures may recur. If they do it is important to check adherence to simple lifestyle factors and consider prescribing a regular laxative to ensure stools and soft and easily pass. Consider a referral to colorectal surgeons for recurrent fissures as patients may require endoscopy and surgical intervention.

Surgical management

A variety of surgical options are available for patients with chronic anal fissures. These depend on the risk of incontinence to the patient and can include:

- Lateral internal sphincterotomy

- Botox injection

- Fissurectomy

- Anal advancement flap

Last updated: June 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback