Colonic ischaemia

Notes

Introduction

Colonic ischaemia refers to insufficient blood supply to the large bowel.

Intestinal ischaemia occurs when blood flow to the intestines (small and large bowel) is reduced and thereby insufficient for the needs of the intestines. The cause of insufficient blood flow varies and can be occlusive (thrombosis, embolus) or non-occlusive (vasoconstriction, hypoperfusion).

The terminology surrounding intestinal ischaemia can be confusing at times with certain terms used interchangeably. For the purposes of this note we define the following terminology (in line with the general consensus):

- Colonic ischaemia: refers to ischaemia affecting the colon (the focus of this note).

- Mesenteric ischaemia: this term tends to be reserved to describe ischaemia affecting the small intestines.

Colonic ischaemia is most commonly non-occlusive in nature and may spontaneously resolve, though a proportion will develop necrosis and eventual breakdown of luminal integrity.

Epidemiology

Colonic ischaemia has an approximate incidence of 22.9 per 100,000 person-years.

It is the most common form of intestinal ischaemia and incidence increases with advancing age.

Evidence points towards an increasing incidence, likely due to a combination of greater recognition and an ageing population.

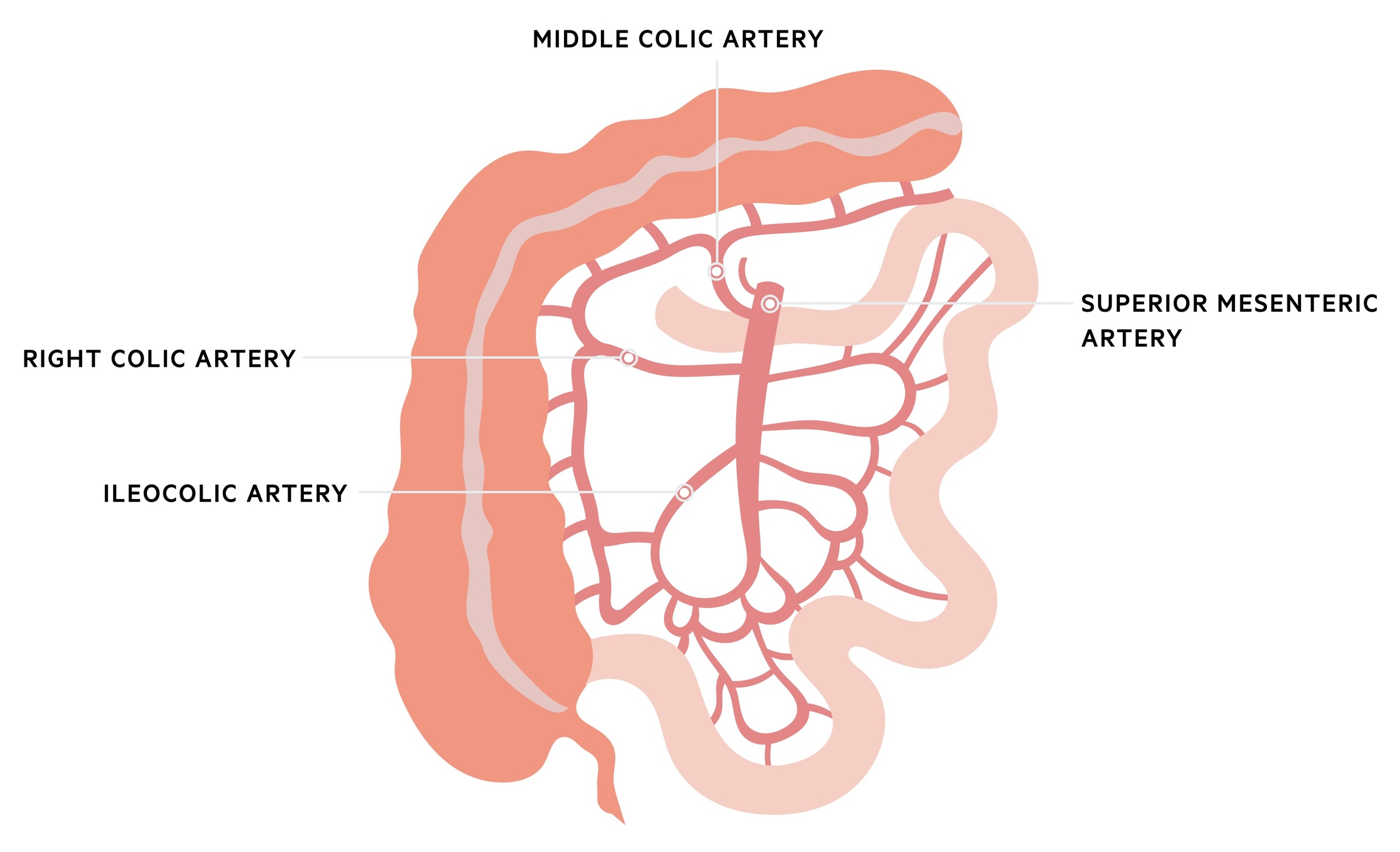

Blood supply

The blood supply to the colon is primarily provided by the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries.

In addition to the mesenteric arteries, the final part of the hindgut is supplied by branches from the internal iliac artery.

There are many branches (detailed below) that supply the colon. The areas they supply cross-over and they have a tendency to anastomose allowing for a degree of collateral supply. The supply is most precarious at so called ‘watershed’ areas, where such collaterals are limited - namely at the splenic flexure and rectosigmoid junction.

Midgut (colonic component)

The superior mesenteric artery (SMA), the major artery of the midgut, arises from the abdominal aorta at the L1 vertebral level. It provides a number of branches that supply the colon:

- Ileocolic artery: arises from the SMA close to the root of the small intestine mesentery. It descends within the mesentery toward the caecum commonly dividing into an inferior and superior branch. The inferior branch passes to the ileocolic junction and divides into anterior and posterior caecal arteries, the appendiceal artery and an ileal branch. The superior branch passes upwards and anastomoses with the right colic artery.

- Right colic artery: the anatomy of the right colic artery is highly variable. It may arise from a common trunk with the middle colic artery, the SMA itself or even the ileocolic artery. It passes toward the ascending colon and divides into the ascending branch that anastomoses with the middle colic artery and a descending branch that anastomoses with the superior branch of the ileocolic artery.

- Middle colic artery: arises from a common trunk with the right colic or directly from the SMA. It passes toward the transverse colon and divides into a variable number of branches. Commonly there is a left and right branch, the left anastomosing with the left colic artery at the splenic flexure and the right anastomosing with the right colic. Additionally a middle branch may be present.

Venous drainage of the midgut largely mirrors the arterial supply with the superior mesenteric vein joining the splenic vein to form the portal vein.

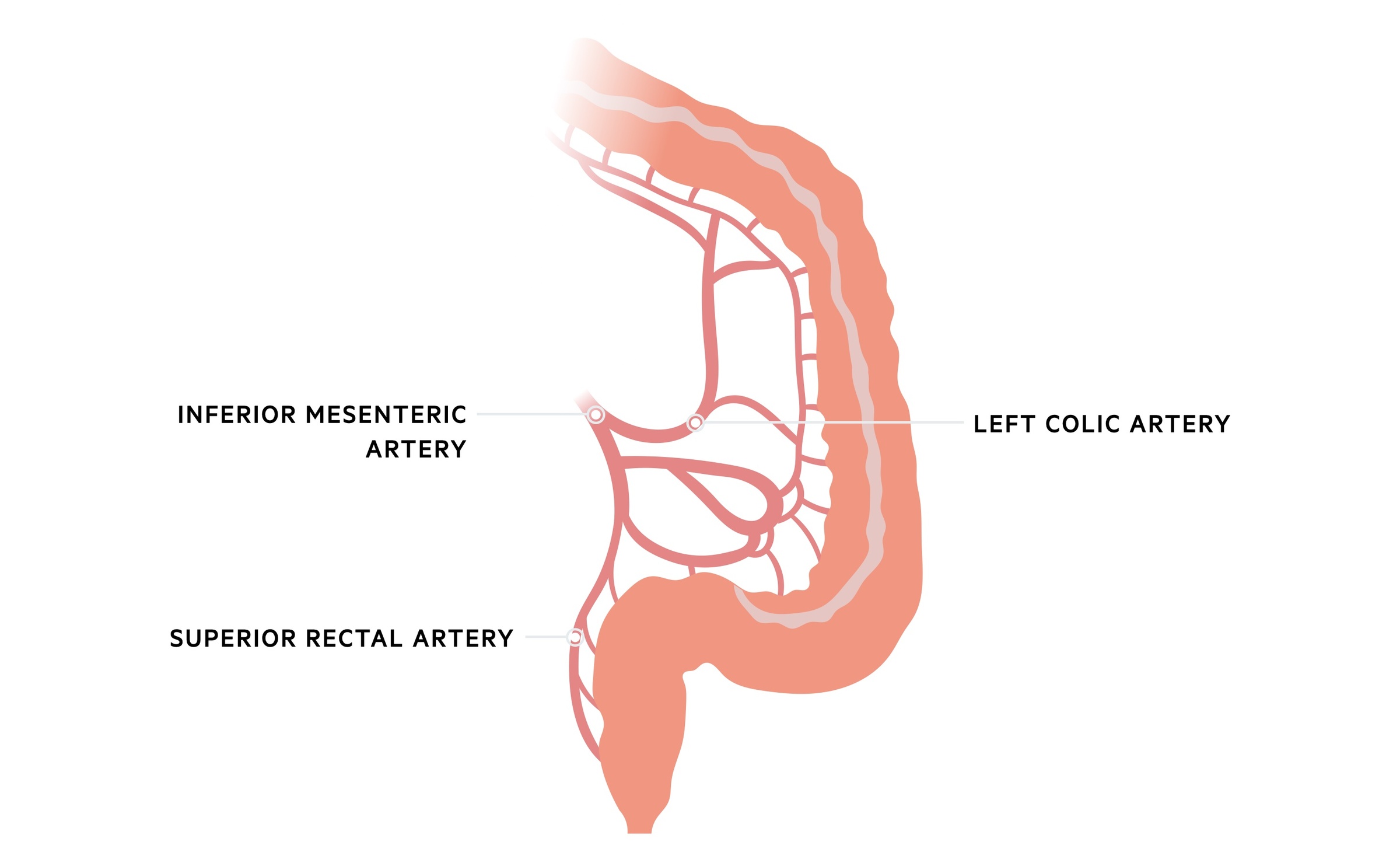

Hindgut

The inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) supplies the hindgut. It arises from the abdominal aorta at the level of the third lumber vertebra. It gives of a number of branches to supply the colon:

- Left colic artery: arises from the IMA and runs to the descending colon, dividing into ascending and descending branches. The ascending branch anastomoses with branches of the middle colic whilst the descending branches meet sigmoid arteries below.

- Sigmoid artery: a variable number (normally 2-5) of sigmoid arteries arise from the IMA and supply the distal descending colon and sigmoid colon.

- Superior rectal artery: a continuation of the IMA as it crosses the pelvic brim, the superior rectal artery supplies the upper two-thirds of the rectum.

The middle and inferior rectal arteries arise from the internal iliac artery or its branches. The middle rectal arteries tends to arise either from the internal iliac or the inferior vesical/vaginal artery. The inferior rectal arteries are a continuation of the internal pudendal arteries.

Marginal artery of Drummond

The SMA and IMA contribute to the formation of the marginal artery of Drummond, a vessel that runs along the inner margin of the colon providing branches to the bowel wall. It receives contributions from the ileocolic, right, middle and left colic arteries. It is at times absent or very small at the splenic flexure and is less well developed at the sigmoid region.

Aetiology

Colonic ischaemia may be non-occlusive or occlusive in nature.

Non-occlusive

Non-occlusive disease is characterised by reduced perfusion to the colon not explained by occlusive lesions. It is the most common cause of colonic ischaemia though is normally transient. If prolonged it can result in bowel wall necrosis. It most commonly affects watershed regions where collateral blood supply is poor - the splenic flexure and rectosigmoid junction.

There are a number of risk factors for non-occlusive colonic ischaemia:

- Heart failure (low output state)

- Septic shock

- Vasopressors (e.g. noradrenaline, cause vasoconstriction)

- Recent CABG

- Renal impairment

- Peripheral vascular disease

- Cocaine use

Occlusive

Occlusive disease is characterised by physical impedance of the arterial supply or venous drainage. It occurs relatively rarely in isolation to the colon, with the small intestines commonly also affected.

Arterial

Arterial occlusion may be occur secondary to thrombosis or embolism:

- Mesenteric arterial embolism: this is classically described in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation (a risk factor for left atrial thrombus that can lead to systemic embolism) presenting with severe left sided abdominal pain. It may affect individuals with other risk-factors for embolic disease including those with infective endocarditis, arrhythmia’s, left ventricular aneurysm (increases risk of ventricular thrombus) or proximal atherosclerotic disease.

- Mesenteric arterial thrombosis: tends to occur in vasculopaths with other cardiovascular disease (e.g. peripheral vascular disease). They may have a background of chronic mesenteric ischaemia as characterised by abdominal pain following food and weight loss. Risk factors include peripheral vascular disease, advancing age, iatrogenic trauma (e.g. during surgery) and heart failure.

Venous thrombosis

Venous thrombosis impedes flow and causes stagnation leading to bowel wall oedema and eventual impairment of arterial supply. Thrombosis of the mesenteric veins leading to colonic ischaemia is relatively uncommon. When it occurs, it typically affects the superior mesenteric vein drainage affecting the small intestines and proximal colon. It may occur for a number of reasons including local inflammatory processes (e.g. pancreatitis) and thrombophilia’s.

NOTE: Ischaemia may also result from bowel obstruction - in particular voluvlus, where twisting (normally sigmoid or caecal) of the large bowel can impair the blood supply. We discuss bowel obstruction in more detail here.

Clinical features

Colonic ischaemia classically presents with abdominal pain and bloody diarrhoea.

In symptomatic cases patients normally complain of abdominal pain that may be crampy in nature. This can be accompanied by diarrhoea which at times is bloody. There is a spectrum of disease from mild self-limiting insults to necrosis and bowel perforation.

Clinical exam can be misleading, simply revealing abdominal tenderness despite significant underlying ischaemia. It should be remembered that patients can be systemically well with relatively normal lactates and still have significant ischaemia - often pain - out of keeping with the clinical exam is the most sensitive sign.

Patients may be peritonitic, particularly those with significant persistent ischaemia and perforation / impending perforation. A significant sepsis may be experienced with fevers and haemodynamic instability.

Symptoms

- Abdominal pain

- Diarrhoea

- Haematochezia

- Fever

Signs

- Tenderness

- Peritonism

- Pyrexia

- Tachycardia

- Haemodynamic instability

Investigations

The diagnosis of colonic ischaemia is based on the clinical presentation, imaging +/- endoscopic visualisation & biopsy.

Routine blood tests are sent that often show an inflammatory response. Lacatate is essential and helps guide fluid resuscitation, but must be interpreted with caution. Significant intestinal ischaemia may be present with a normal or minimally elevated lactate and a raised lactate does not confirm the presence of ischaemia.

As discussed in the management section below, the diagnosis of colonic ischaemia can be challenging, particularly in mild disease. Inflammatory and infective colitis may present with similar features and findings on investigation. The investigations will depend in part on the presentation. In stable patients an abdominal CT +/- direct endoscopic visualisation may be organised.

In shocked patients with an acute abdomen you may proceed straight to theatre for a diagnostic laparoscopy/laparotomy, though this would be a consultant lead decision. In reality, given how easily accessible CT is in most A&E departments if the patient is appropriately stabilised a CT scan may still be sought.

Bedside

- Observations

- Blood sugar

Blood tests

- FBC

- Renal function

- LFTs

- CRP

- Clotting screen

- Group and save

- Venous/arterial blood gas (includes a lactate)

Imaging

A CT, typically with arterial phase contrast, should be organised. Though ischaemia can be difficult to definitively diagnose or exclude on CT there are characteristic signs and importantly it helps to evaluate for other causes of an acute abdomen. Findings indicative of colonic ischaemia include bowel dilatation and thickening which may be accompanied by surrounding fat stranding or free fluid. In fulminant disease with perforation, free air can be seen. Occlusion of the mesenteric arteries can sometimes be seen.

Endoscopy

Colonoscopy (or flexible sigmoidoscopy) provides direct visualisation and allows for biopsy. It is not without risks (namely perforation) and should be performed with minimal air insufflation.

Management

The management of colonic ischaemia is complex involving supportive care and surgical intervention in appropriately selected patients.

The management of colonic ischaemia is highly dependent on the individual presentation and risk factors. Many cases will resolve spontaneously with supportive care only, but the clinical course is difficult to predict. Often times the diagnosis is challenging and differentials such as infective or inflammatory colitis can be difficult to exclude.

As such an individualised approach must be taken to each case. The patients presentation, co-morbidities, examination, clinical status and investigations must all be considered and management guided by senior members of the surgical team.

Supportive care

Patients should be made NBM with the decision to reintroduce enteral feeding made by a senior surgeon. A NG tube may be placed particularly in the presence of paralytic ileus.

Appropriate IV fluid resuscitation followed by maintenance fluid should be given. A urinary catheter should generally be placed, particularly in those with sepsis or acute renal impairment to allow for an accurate fluid balance.

Broad spectrum antibiotics are generally given and are essential in patient with perforation and peritonitis. Even in the absence of perforation, ischaemia is thought to predispose patients to increased bacterial translocation.

Non-occlusive pathology

The majority of patients have non-occlusive disease. This often follows a self-limiting course though this can be hard to predict. Any underlying conditions or acute illnesses should be treated.

Occlusive pathology

Anticoagulation can be used in patients with thromboembolic pathology. Unfractionated heparin would typically be preferred in patients who may need surgery though low molecular weight heparin is far more straight forward to use.

In those with thromboembolism and appropriate anatomy, embolectomy, catheter directed thrombolysis or mesenteric angioplasty and stenting may be indicated. As discussed above this is rarely the cause of colonic ischaemia and is more commonly seen in mesenteric ischaemia (i.e. small bowel ischaemia) that can at times affect the proximal colon given the shared SMA blood supply.

Surgical intervention

Surgery tends to be indicated in patients with severe colonic ischaemia, peritonitis on examination or evidence of perforation or impending perforation. The decision to proceed to surgery is not always straightforward and should be consultant led.

Surgical exploration will generally require a laparotomy though there may be a role for laparoscopy from a diagnostic viewpoint. With the appropriate local expertise, laparoscopy may also be used to complete the colonic resection. The bowel can be examined visually and ischaemic segments resected. Generally speaking primary anastomosis is avoided and a stoma formed instead with a plan to reverse in a second procedure (at 3-6 months) if deemed appropriate.

Some patients will not be suitable surgical candidates or may decline surgery. It should be remembered colonic ischaemia often occurs in elderly, co-morbid patients during another acute illness. A conservative approach, with input from palliative care may be more appropriate in this setting.

Last updated: October 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback