Haemorrhoids

Notes

Overview

Haemorrhoids refer to abnormally swollen vascular cushions that are located in the anal canal.

Haemorrhoids are essentially a cluster of vascular, smooth muscle, and connective tissue that lies along the anal canal in three columns. These are often referred to as mucosal anal cushions or haemorrhoidal cushions. These cushions are actually normal anorectal structures that are found universally in healthy individuals.

In clinical practice, we use the term ‘haemorrhoids’ to refer to the symptomatic enlargement and displacement of the normal haemorrhoidal cushions that can lead to perineal irritation, anal itching, fecal soiling, and most commonly painless rectal bleeding.

Haemorrhoids are extremely common in the population and colloquially known as ‘piles’. It is estimated that the prevalence is 11% in the general population with an equal sex prevalence and peak between ages 45-65.

Classification

Haemorrhoids may be internal or external based on their relationship with the dentate line.

Haemorrhoids can be broadly divided into internal or external based on their location relative to the dentate line.

- Internal: haemorrhoids located proximal to the dentate line

- External: haemorrhoids located distal to the dentate line

NOTE: haemorrhoids may be mixed if they are located both proximal and distal to the dentate line.

Dentate line

The dentate line divides the upper two-thirds of the anal canal from the lower third of the anal canal. The upper two-thirds are lined by rectal columnar epithelium and the lower two-thirds by stratified squamous epithelium.

The squamous epithelium is highly innervated with pain fibres so external haemorrhoids are often itchy and painful. The columnar epithelium above the dentate line does not contain any pain fibres so internal haemorrhoids are usually painless (unless strangulated).

Grading internal haemorrhoids

Internal haemorrhoids may be further classified into grades I-IV based on the degree to which they prolapse through the anal canal:

- Grade I: visualised on anoscopy and may budge into the lumen but do not prolapse below the dentate line

- Grade II: prolapse out of the anal canal with defaecation or straining but reduce spontaneously

- Grade III: prolapse out of the anal canal with defaecation or straining and need manual reduction

- Grade IV: prolapsed haemorrhoids that are irreducible and at risk of strangulation

Aetiology & pathophysiology

Symptomatic haemorrhoids are thought to develop when supporting tissue with the anal cushions deteriorate.

The anus forms the last part of the gastrointestinal tract. Within the anal canal are anal cushions that help maintain continence. These cushions contain normal haemorrhoidal veins within the submucosa. It is the abnormal downward displacement of these cushions that leads to venous dilatation and symptomatic haemorrhoids.

Factors that are thought to contribute to the loss of normal anal cushion function include a deterioration in connective tissue, increased internal anal sphincter tone, and dilatation of arteriovenous anastomoses within the anal cushions and dilatation of veins within the haemorrhoidal venous plexus.

Internal haemorrhoid locations

Internal haemorrhoids develop from superior haemorrhoidal cushions in three primary locations:

- Left lateral: 3 o’clock position

- Right anterior: 11 o’clock position

- Right posterior: 7 o’clock position

When assessing anal pathology, describing a lesion with reference to a clock face can be used. This anal clock system denotes that 12 o’clock is anterior when the patient is in the lithotomy position (i.e. nearest to the genitalia).

Risk factors

Constipation and prolonged straining to pass stools are widely considered risk factors for the development of haemorrhoids but whether this relationship is causal is not clear. Other factors that have been linked with haemorrhoids include diarrhoea, pregnancy, increased age, prolonged sitting, anticoagulation use and pelvic tumours.

Clinical features

Painless rectal bleeding is the most common feature of haemorrhoids that is often noticing on wiping.

It is estimated that up to 40% of individuals with haemorrhoids are asymptomatic. When symptomatic, patients commonly complain of painless rectal bleeding. This is often seen as bright red blood on wiping with the toilet paper or coating the stool at the end of defaecation.

Systemic symptoms (e.g. weight loss, fever, chronic diarrhoea, abdominal pain) should make you search for an alternative cause. Unexplained PR bleeding may be a feature of colorectal cancer or colitis so it is important to consider other symptoms, the patients' age, and family history.

Symptoms

- Perianal irritation

- Bright red rectal bleeding: usually seen on wiping or coating the stool at the end of defaecation. Commonly painless.

- Faecal incontinence (usually mild): often due to prolapse of haemorrhoids and subsequent leakage

- Mucous discharge: due to internal haemorrhoids covered with columnar epithelium

- Fullness in perianal area

- Pain: overt pain is uncommon unless there is a strangulated haemorrhoid or thrombosis of a haemorrhoid

Signs

In suspected haemorrhoids, it is important to do a careful examination of the anal verge followed by a digital rectal examination in the left lateral position. This also helps to exclude other anorectal pathologies (e.g. fissure, skin tag, tumour).

- Normal examination: may be found if only non-prolapsed internal haemorrhoids are present

- Prolapsed internal haemorrhoid: seen as a bluish, bulging lesion on straining

- External haemorrhoid: seen as a bluish bulging lesion

- Thromboses haemorrhoid: if acute, will be extremely painful, purplish, oedematous perianal mass

Diagnosis & investigations

A diagnosis of haemorrhoids can be made through clinical history, physical examination, and excluding alternative pathologies.

The diagnosis of haemorrhoids is usually suggested by the history of bright red rectal bleeding on wiping with perianal irritation. This is then followed by a clinical examination to visualise the anorectal region and identify haemorrhoids. A formal diagnosis is made by direct visualisation. To ensure the entire anal canal is visualised this usually requires a procedure (e.g. proctoscope)

The European Society of Coloproctology advises that a procedure (e.g. rigid anoscope, proctoscope or rectoscope) should be used to visualise the entire anal canal to diagnose and classify haemorrhoids. If the facilities or expertise are not available to perform this in primary care, then patients may need to be referred for further assessment.

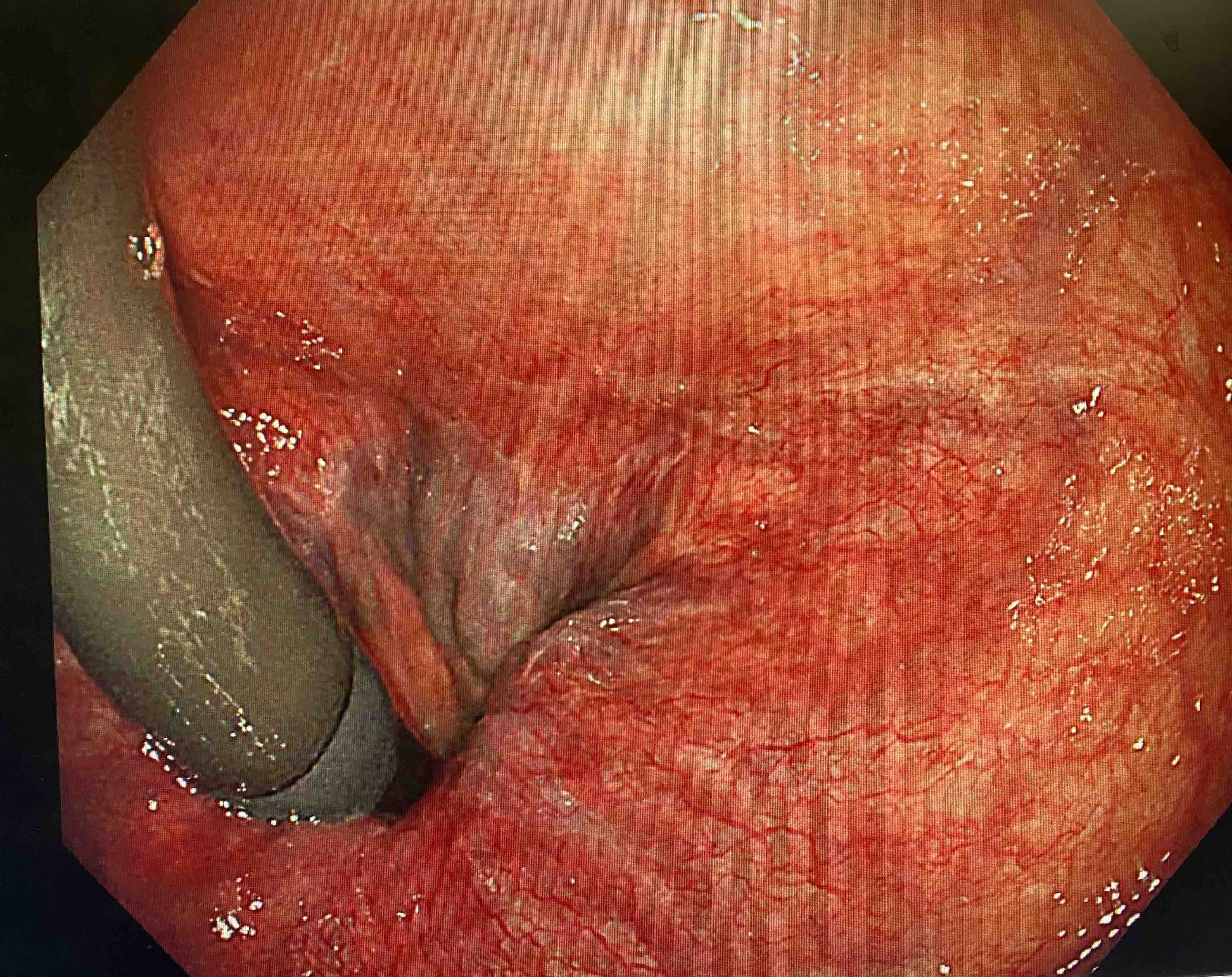

Grade I internal haemorrhoids

Seen on retroflexion during colonoscopy

Differential diagnosis

Many conditions may also present with anorectal symptoms and the presence of haemorrhoids does not exclude other pathology. Therefore, it is vital to take a thorough history and perform a good clinical examination to exclude other causes.

The major differentials to consider include:

- Anorectal polyp

- Anal fissure

- Cancer: Anal or colorectal

- Anorectal fistula

- Diverticular disease

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Perianal abscess

- Rectal prolapse

- Sexually transmitted infection

Laboratory tests

In patients with clinical signs of anaemia or significant rectal bleeding, it is important to arrange a full blood count and consider iron studies. Unexplained iron-deficiency anaemia is concerning and warrants urgent referral for investigation of gastrointestinal cancer.

Endoscopic assessment

A basic procedure such as anoscopy or proctoscopy should ideally be used to diagnose and classify haemorrhoids. They are also useful to exclude alternative anal pathologies (e.g. fistula, fissure, polyp).

More invasive endoscopic assessment including flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy depends on the clinical presentation and suspected underlying cause. For example, patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease or colorectal cancer need an urgent referral for colonoscopy (e.g. patients with positive qFIT, patients > 60 with change in bowel habits).

Referral

If there is a concern for another cause (e.g. inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer) patients should be referred appropriately. Ensure you are familiar with the lower GI two-week wait pathway referral criteria, which are discussed further in our Colorectal cancer note.

Management

The management of haemorrhoids depends on the type and severity.

All patients with haemorrhoids should be advised of basic treatment. If this fails, then patients can be referred for more invasive management.

Basic treatment

It is important to explain to patients that following a diagnosis of haemorrhoids surgical treatment is not mandatory. In fact, the first steps involve basic treatment and advice. This includes:

- Healthy lifestyle measures: consuming sufficient water intake, maintaining a healthy diet with high fibre intake to prevent constipation and undertaking physical activity

- Toilet training: patients should be advised to adopt the correct position during defaecation, avoid straining and prolonged periods on the toilet

- Avoiding medications that cause constipation (e.g. codeine)

- Laxatives (e.g. bulk, stimulant, osmotic or softeners): these may be used to prevent constipation and reduce bleeding

- Analgesia: consider NSAIDs and non-opioid analgesics for any pain or significant irritation

- Medical therapies (see below)

Medical therapies

A variety of medical therapies are available for patients with haemorrhoids. Many of these can be bought over the counter without the need for a prescription. Options include:

- Topical agents: both anaesthetic agents and steroids can be prescribed for symptomatic relief. However, the evidence supporting topical agents is limited. These topical agents can be used for acute pain but should ideally not be continued for longer than 1 week. Topical steroids are thought to shrink haemorrhoids and relieve pruritus.

- Venoactive agents: these are also known as phlebotonics. They aim to increase venous tone and reduce bleeding but also help with other perianal symptoms such as irritation. Options include flavonoids and calcium dobesilate.

- Antispasmodic agents: these agents help to reduce anal sphincter spasms that may contribute to perianal symptoms. More commonly used in patients with anal fissures. Examples include topical 0.5% nitroglycerin ointment

Surgical treatments

In patients with persistent symptoms despite basic treatment including medical therapies, surgical options can be offered. There is a range of surgical options and the choice depends on the types and severity of haemorrhoids and patient preference.

In general, due to the innervation, a range of therapies may be offered for internal haemorrhoids including rubber band ligation, sclerotherapy, infrared coagulation or haemorrhoidectomy. Many of these therapies can be completed in an outpatient environment without minimal or no anaesthesia. Conversely, external haemorrhoids that require treatment usually need surgical management because the area is highly innervated by somatic nerves and therefore more sensitive to treatments (some exceptions exist).

Surgical options:

- Rubber band ligation: a minimally invasive technique that involves placing a rubber band at the base of the haemorrhoid to stop blood flow. This can be completed with or without an endoscope. This may be offered first line to patients with grade I-III internal haemorrhoids

- Sclerotherapy: involves the injection of a sclerosant agent into the internal haemorrhoid. This causes an inflammatory reaction that destroys submucosal tissue associated with the haemorrhoid. Commonly used for grade I-II haemorrhoids

- Infrared coagulation: involves the direct application of infrared light waves to haemorrhoidal tissue. An option for patients with grade I-II haemorrhoids

- Haemorrhoidectomy: involves surgical removal of haemorrhoids through different techniques depending on whether they are external or internal haemorrhoids. This is usually reserved for patients with severe symptomatic external haemorrhoids or grade III-IV internal haemorrhoids that have failed previous treatment options. The various different techniques are beyond the scope of these notes.

When considering haemorrhoidectomy, it is important that patients are aware of the various success rates and complications. Pain is a very common complication following intervention and can be severe. Major complications include bleeding, faecal incontinence and anal stricture.

Complications

Many complications may be associated with haemorrhoids, but overall significant anaemia from excessive bleeding is rare.

- Perianal thrombosis

- Incarcerated prolapsed haemorrhoid

- Strangulated prolapsed haemorrhoid

- Ulceration: from thromboses external haemorrhoid

- Skin tags

- Anal stenosis

- Perianal infection

- Anaemia from excess bleeding

Last updated: June 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback