Chronic pancreatitis

Notes

Overview

Chronic pancreatitis refers to chronic, irreversible, inflammation and/or fibrosis of the pancreas.

Chronic pancreatitis is traditionally considered as chronic, irreversible, inflammation and/or fibrosis of the pancreas. It is essentially a fibroinflammatory syndrome (evidence of fibrosis and inflammation) that occurs in patients with genetic and/or environmental risk factors for pancreatic injury.

In the Western world, the leading cause of chronic pancreatitis is alcohol. Injury leads to structural and/or functional changes that include atrophy, calcification, strictures, exocrine dysfunction, endocrine dysfunction, and even increased risk of pancreatic cancer. Management centres on pain control and endoscopic or surgical treatment of complications.

Exocrine and endocrine dysfunction

Chronic pancreatitis is characterised by pain, endocrine dysfunction, and exocrine dysfunction.

- Endocrine dysfunction: damage to the islet cells result in lack of insulin and development of diabetes mellitus

- Exocrine dysfunction: damage to the acinar cells results in lack of pancreatic enzymes and malabsorption

Terminology

Chronic pancreatitis lies on a spectrum of pancreatic injury that includes acute pancreatitis, acute recurrent pancreatitis, and chronic pancreatitis. In some cases, there is significant overlap and a clear distinction is not possible.

- Acute pancreatitis: self-limiting, reversible pancreatic injury associated with epigastric pain and pancreatic enzyme elevation

- Acute recurrent pancreatitis: the presence of ≥2 distinct episodes of acute pancreatitis without evidence of underlying chronic pancreatitis

- Idiopathic pancreatitis: used when no cause can be identified for pancreatitis despite extensive evaluation

- Chronic pancreatitis: no clear definition but evidenced by fibroinflammatory changes in the pancreas and endocrine/exocrine dysfunction

The term ‘acute-on-chronic’ pancreatitis may also be used in clinical practice that can be confusing. It may refer to a clear episode of acute pancreatitis on the background of chronic pancreatitis changes or ‘acute exacerbations’ of chronic pancreatitis (e.g. worsening pain) secondary to ongoing low-grade structural and/or inflammatory changes that may only be noticeable on tissue sampling.

Epidemiology

Chronic pancreatitis is an under-recognised condition.

The incidence of chronic pancreatitis is around 8.6 per 100,000 population per year in the UK. The global prevalence of chronic pancreatitis varies and has been estimated between 13.5-52.4 per 100,000 population. The age of onset is largely dependent on the aetiology. Alcohol is the most common cause in Western populations seen in up to 80% of cases.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

There are a huge number of causes of chronic pancreatitis and patients often have more than one aetiological factor.

There are many causes of chronic pancreatitis. Examples include alcohol, high triglycerides or autoimmune pancreatitis. Many of these causes have different aetiological mechanisms leading to chronic pancreatic damage. In fact, multiple factors may be present in the same patient that collectively increases the risk of progression to chronic pancreatitis.

Natural history

The actual pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for chronic pancreatitis are incompletely understood. While the mechanisms depend on the aetiology, as the disease progresses there is a commonality between the causes with loss of normal pancreatic tissue (e.g. acinar, islet and ductal cells), development of fibrosis, formation of calcification, and ultimately loss of pancreatic function.

In its early stages, pain may be prominent and intermittent but the pancreas often appears normal on imaging. As the disease progresses, pain becomes more persistent and continuous with obvious structural and functional changes in the pancreas.

TIGAR-O classification

The TIGAR-O classification is used to group the causes of pancreatitis into six major groups.

- T (toxic/metabolic): alcohol, smoking, high triglycerides, hypercalcaemia, chronic kidney disease

- I (idiopathic): no known cause. May be early-onset (< 20 years), late-onset (median age 56), or tropical (largely confined to Southern India in children)

- G (genetic): genetics is quite complex in chronic pancreatitis. The term hereditary pancreatitis is usually reserved for mutations in PRSS1 that show autosomal dominant inheritance. Other culprit genes may have autosomal recessive or more complex inheritance patterns

- A (autoimmune): there are two types of autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP). Type 1 is a manifestation of IgG4 disease due to tissue deposition and subsequent damage by IgG4-positive plasma cells. The pancreas is one of many organs that can be affected. Type 2 is limited to the pancreas and associated with inflammatory bowel disease

- R (recurrent and severe acute pancreatitis): patients with a severe episode of necrotising pancreatitis or those with acute recurrent pancreatitis can progress to chronic pancreatitis due to tissue destruction. After a single attack of acute pancreatitis, approximately 10% progress to chronic pancreatitis

- O (obstructive factors): chronic obstruction of the main pancreatic duct can lead to tissue damage and chronic pancreatitis upstream. Typical causes of obstruction include strictures, stones, cysts, and tumours

Alcoholic chronic pancreatitis

Alcohol is the most common cause of chronic pancreatitis in the Western world. It is estimated that an intake of 5 or more drinks per day is needed for the development of chronic pancreatitis. However, < 5% of patients with heavy alcohol consumption develop the condition suggesting other factors contribute. Patients may present with acute recurrent pancreatitis that subsequently progresses to chronic pancreatitis. Others may present with an acute episode but already have features suggestive of chronic pancreatic changes on imaging (e.g. calcification).

Autoimmune pancreatitis

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a complex condition that refers to two conditions:

- Type 1 AIP: part of a systemic condition called IgG4-related diseases. It is due to the infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells into the pancreas and other tissues. It can cause pancreatitis, sclerosing cholangitis and many other conditions.

- Type 2 AIP: a type of pancreatitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease but limited to the pancreas

Hereditary pancreatitis

This refers to the development of acute recurrent pancreatitis or chronic pancreatitis by the inheritance of abnormal genes through a mendelian pattern of inheritance (this classically refers to autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive inheritance).

The classic examples of hereditary pancreatitis include:

- Autosomal dominant: secondary to PRSS1 mutation. Encodes cationic trypsinogen

- Autosomal recessive: associated with mutations in the CTFR gene (abnormal in cystic fibrosis) and SPINK1 gene known as pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor gene

- Complex genetics: typically related to the inheritance of ‘gene modifiers’ such as a patient who is heterozygous for SPINK1 (i.e. one abnormal copy, one normal copy). By themselves, these genes do not cause pancreatitis but they increase the risk, especially when combined with environmental risk factors (e.g. alcohol, smoking)

Clinical features

The hallmark feature of chronic pancreatitis is abdominal pain.

Abdominal pain is usually the most common feature of chronic pancreatitis and the leading reason for endoscopic or surgical intervention in this patient group. A small proportion of patients will be pain-free (i.e. asymptomatic).

Other features are related to the malabsorption from pancreatic exocrine insufficiency or the complications associated with endocrine insufficiency. Clinical features also depend on the underlying aetiology.

Pain syndrome

Pain is very common in chronic pancreatitis. It is typically felt as an epigastric discomfort that may be worse on lying down and after eating (i.e. post-prandial). It may be associated with other features including:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Anorexia

The aetiology of the pain is complex and thought to be generated by high pressure, tissue ischaemia, ongoing inflammation and alternation in pain signalling from the pancreas. Importantly, the severity of pain does not correlate with the amount of pancreatic damage on imaging.

Exocrine insufficiency

Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) refers to the loss of important digestive enzymes from the pancreas due to the destruction of the normal pancreatic acinar cells. This leads to malabsorption as patients are unable to digest their normal diet, particularly fatty foods due to the lack of pancreatic lipase. Features of PEI include:

- Weight loss

- Bloating

- Flatulence

- Abdominal pain/discomfort

- Loose stools

- Steatorrhea: refers to oily or greasy stools that typically float and are difficult to flush away (due to fat maldigestion)

Importantly, > 90% of the pancreatic exocrine function needs to be lost before patients develop steatorrhea. Therefore, it is a consequence of long-standing pancreatic damage.

Endocrine insufficiency

The loss of islet cells within the pancreas leads to the development of diabetes mellitus. In the nomenclature, this is typically described as type 3c diabetes mellitus (i.e. pancreatogenic origin). Other causes include cystic fibrosis, pancreatic cancer or hereditary haemochromatosis. It leads to similar clinical features of diabetes, which include:

- Polyuria

- Polydipsia

- Weight loss

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is traditionally made on imaging.

The diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis is usually based on imaging by looking for structural and/or functional abnormalities that are supportive of chronic pancreatic damage. Histology can provide a ‘gold-standard’ diagnostic tool for chronic pancreatitis but is seldom completed due to its invasive nature and high variability in interpretation.

Imaging

CT or MRI with MRCP are the best imaging modalities for the assessment of chronic pancreatitis. They should be requested in patients with suspected pancreatitis based on typical symptoms or findings of exocrine/endocrine insufficiency. However, in the early stages of chronic pancreatitis, imaging may not demonstrate conclusive evidence of pancreatitis that may lead to more invasive assessment with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with or without biopsy.

Chronic pancreatitis may often be suggested in patients undergoing imaging (e.g. CT) for other reasons (e.g. investigation of acute abdominal pain). These patients require referral for investigation of chronic pancreatitis and often require repeat dedicated imaging of the pancreas.

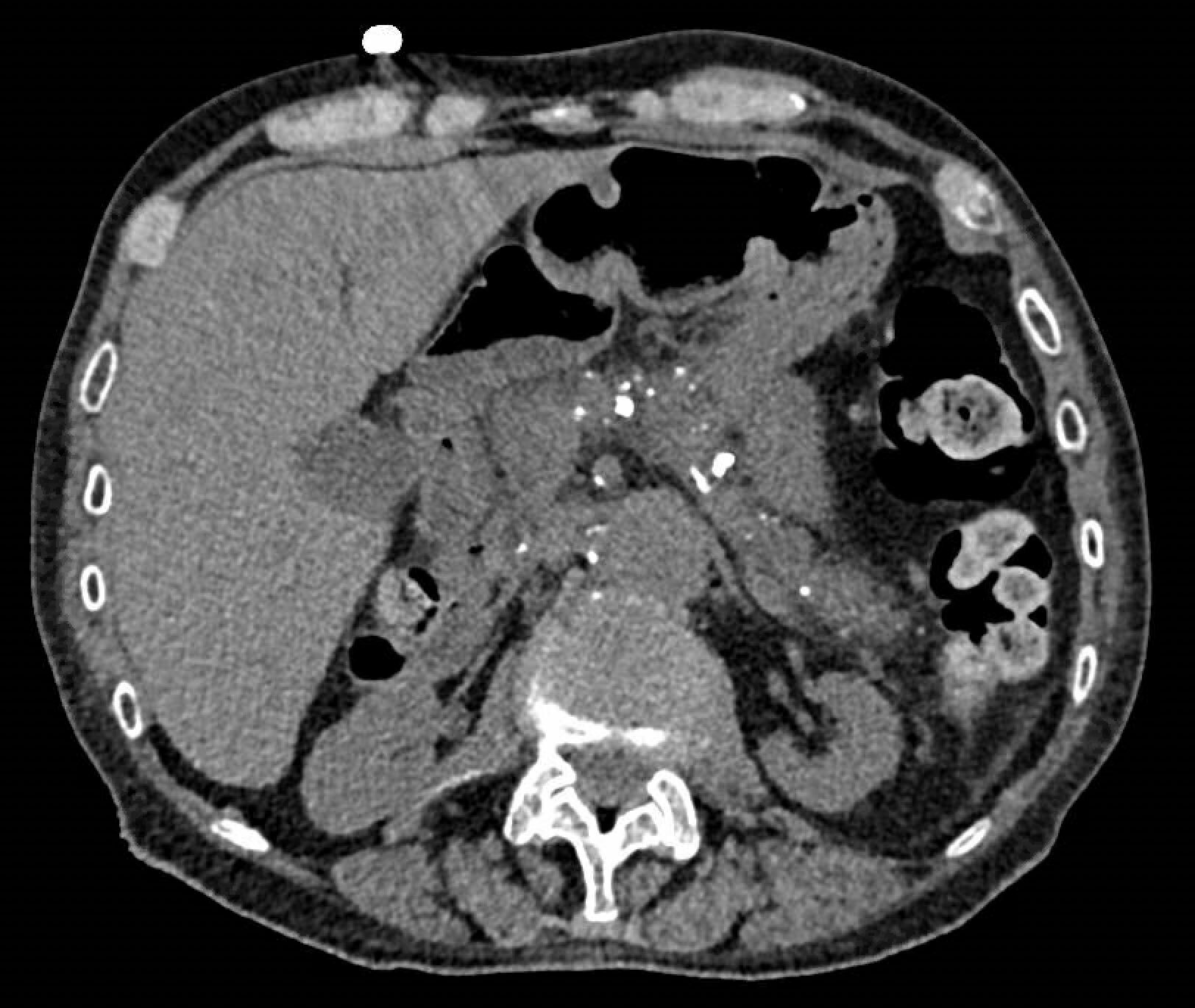

CT showing chronic pancreatitis with calcification (white densities in the centre of the image)

CT

CT is the most commonly utilised imaging modality for chronic pancreatitis. It has a higher sensitivity but similar specificity to ultrasound. CT is excellent at looking for calcification changes within the pancreas. Features of chronic pancreatitis include atrophy, calcification, and ductal changes (e.g. dilatation, strictures).

MRI/MRCP

MRI combined with MRCP gives a much more detailed picture of the pancreatic ducts. It is also useful for looking at cystic structures within the pancreas. At the time of the MRI, secretin may be administered to both improve the assessment of the main pancreatic duct and to assess the degree of ductal secretion. This is a direct test of pancreatic function, but its use is limited in the UK.

EUS

Endoscopic ultrasound is a newer imaging modality that allows assessment of the pancreatic tissue via a small ultrasound on a specialised endoscope. It provides a highly detailed examination of the ducts and parenchyma that can be used alongside certain diagnostic criteria. However, features on EUS are not specific and there is interobserver variability (sensitivity > 80%, specificity up to 100%). EUS has the added benefit that biopsies can be taken at the time of the procedure for histology.

Investigations

Patients with confirmed or suspected chronic pancreatitis need a comprehensive work-up.

Once the diagnosis is suspected or confirmed on imaging, patients usually require a comprehensive work-up to determine the cause of chronic pancreatitis and to assess for complications such as exocrine and endocrine insufficiency.

Bedside tests

- Capillary blood glucose

- Faecal elastase

Faecal elastase is an indirect marker of pancreatic function. It is a stool test to assess for pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI). It is an enzyme released by the pancreas and low levels suggest PEI. A level < 100 mcg/g is usually consistent with PEI. False positives can occur in patients with loose, watery stools due to a dilution effect. It is not as useful for patients with mild or even moderate PEI.

Bloods

- Full blood count

- Urea & electrolytes

- Liver function tests

- Lipid profile

- Bone profile

- Magnesium

- HbA1c

- Vitamin D

Imaging

- CT: enables confirmation of diagnosis and to assess for possible cause

- MRI/MRCP: enables confirmation of diagnosis and better at assessing ducts (e.g. strictures, irregularities)

- US: useful to assess for gallstones

- EUS: aids the diagnosis and assessment of the ducts. Enables tissue samples to be taken for histology

Special tests

- Bone mineral density: at risk of osteoporosis

- Genetic testing: consider if idiopathic chronic pancreatitis or strong family history

- IgG subsets: specifically for autoimmune pancreatitis

Management

The management of chronic pancreatitis is complex and involves analgesia, endoscopic and surgical treatments.

The management of chronic pancreatitis is highly complex and depends on the structural and/or functional abnormalities that develop within the gland. There is a growing role for endoscopic therapy in patients with ductal abnormalities and surgery is usually reserved for patients with chronic pain despite adequate analgesia, endoscopic therapy, and optimisation of co-morbidities.

Basic management

All patients should undergo nutritional assessment (e.g. review by a dietitian if required), alcohol cessation (if this is the cause of chronic pancreatitis), and smoking cessation. Patients may require dietary supplementation and replacement of important vitamins (e.g. vitamin D).

Pain control

Analgesia forms the cornerstone of management in chronic pancreatitis. Basic analgesics should be used first including paracetamol and NSAIDs (if no contraindications). If pain is not controlled weak opioids (e.g. codeine, tramadol) can be added. Unfortunately, patients often require increasing doses of strong opioids but this should be avoided where possible.

If patients require increasing use of analgesic agents, adjuncts should be opted for, which include:

- Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. low dose amitriptyline)

- Serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- Gabapentoids (e.g. gabapentin, pregabalin)

In patients with difficult to control pain, referral to a pain clinic is usually very helpful.

Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency

Patients with evidence of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency should be started on pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT). Patients are typically advised to take 40,000 - 50,000 units with main meals and 25,000 units with snacks. Commercial PERT are dosed based on their lipase content and range from 3,000 - 40,000 units. They can come as capsules, resistant granules, or powders.

Absorption can be improved by increasing the dose or adding acid-suppression therapy (e.g. omeprazole).

Diabetes mellitus

Patients with diabetes mellitus should be managed by appropriate clinicians (e.g. GP, endocrinologists). Insulin is commonly required due to pancreatic gland destruction although doses are usually less when compared to patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Metformin is an option for patients who do not yet require insulin.

Endoscopic management

There is a growing role for endoscopy in the management of chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopic therapy is generally indicated when there are structural abnormalities present within or around the pancreas that can be treated. Examples include:

- Pancreatic pseudocysts

- Pancreatic stones

- Main pancreatic duct strictures

- Other complications (e.g. biliary strictures, duodenal obstruction)

Patients with painful chronic pancreatitis and evidence of main duct stricturing can undergo ERCP and pancreatic stenting with either plastic or self-expanding metal stents. Newer cholangioscopy can be used to help treat pancreatic ductal stones. Endoscopy can also be used to enable access for a coeliac plexus block to provide pain control. This involves injection of local anaesthetic around the coeliac plexus using endoscopic ultrasound. However, this is effective in just over half of patients.

Surgical management

Surgery is a possibility in patients with chronic pancreatitis and may involve drainage procedures in those with obstruction, or resection procedures in those with unremitting pain but normal calibre ducts. Typical indications for surgery include intractable resistant pain, failure of previous drainage procedures, suspicion of malignancy or duodenal stenosis, amongst others.

There are various surgical procedures that can be opted for, which largely depend on the diameter of the main pancreatic duct and the location of the major structural changes. Typical options for intractable pain include:

- Lateral pancreaticojejunostomy (Puestow procedure)

- Lateral pancreaticojejunostomy with pancreatic head resection (Frey procedure)

- Classic pancreaticoduodenectomy (i.e. Whipples)

- Distal pancreatectomy

- Total pancreatectomy and islet transplantation

Complications

Chronic pancreatitis is associated with an increased mortality and severely impacts quality of life.

Chronic pancreatitis is associated with a 2-13 fold increase risk of mortality and pancreatic exocrine insufficiency is considered an independent risk factor for mortality.

Typical complications associated with chronic pancreatitis include:

- Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency

- Diabetes mellitus

- Metabolic bone disease (e.g. osteoporosis)

- Pancreatic cancer (risk increases with duration of disease)

- Pseudocysts

- Duodenal obstruction

- Biliary obstruction

Last updated: March 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback