Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Notes

Overview

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is the most common form of pancreatic cancer and a major cause of cancer-related death.

They arise from the ductal epithelium as the result of accumulated genetic mutations. Adenocarcinomas are the most common pancreatic neoplasm, accounting for around 85% of cases.

Asymptomatic through much of its development, sadly this cancer is commonly diagnosed at a late stage when the chance of cure is faint. When caught early, surgery may offer a chance at curative therapy.

Epidemiology

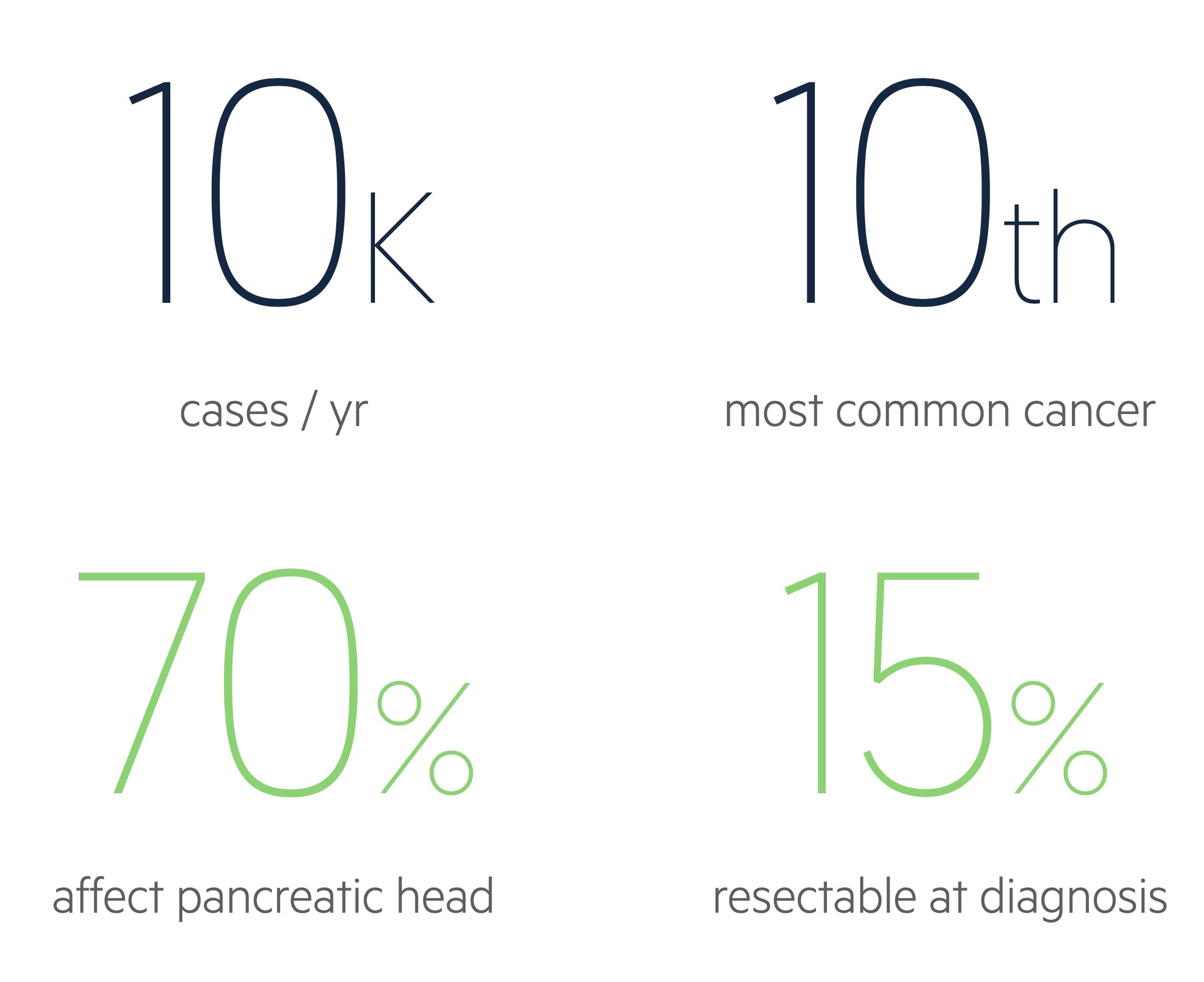

There are approximately 10,500 cases of pancreatic cancer each year in the UK.

Overall it is the tenth most common cancer in the UK, though is the sixth most common cause of cancer death.

It is the ninth most common cancer (around 5,100) in females and the twelfth most common (around 5,400) in men in the UK. Incidence is highest in those aged 85-89 with around 47% of cases occurring in those above the age of 75.

Pancreatic cancer appears to affect those of Black and White ethnicity more than those of Asian heritage.

Figures from Cancer Research UK (last accessed Nov 2021).

Risk factors

A number of risk factors are associated with the development of pancreatic cancer.

- Age

- Smoking

- Alcohol

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Genetic factors

- Hereditary syndromes (e.g. BRCA2, FAMMM, Peutz-Jeghers, hereditary pancreatitis)

- Diabetes

Genetics plays a significant role in the development of pancreatic cancer. Those with two first-degree relatives affected have an 18 times increased relative risk of developing pancreatic cancer. Those with hereditary pancreatitis (with a PRSS-1 mutation) are at 50 times increased risk.

Pathophysiology

Our understanding of the pathogenesis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma continues to develop but remains incomplete.

It is thought that many adenocarcinomas arise from precursor lesions - pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias (PanIN). Three grades of PanIN exist, with progressively increasing dysplasia and in some cases eventual invasive pancreatic adenocarcinoma. KRAS mutations are almost ubiquitous in PanINs and as the grade increases mutations are often found in p53, CDKN2A and SMAD4 tumour suppressors.

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma can also develop from cystic neoplasms. These include intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) and mucinous cystic neoplasia.

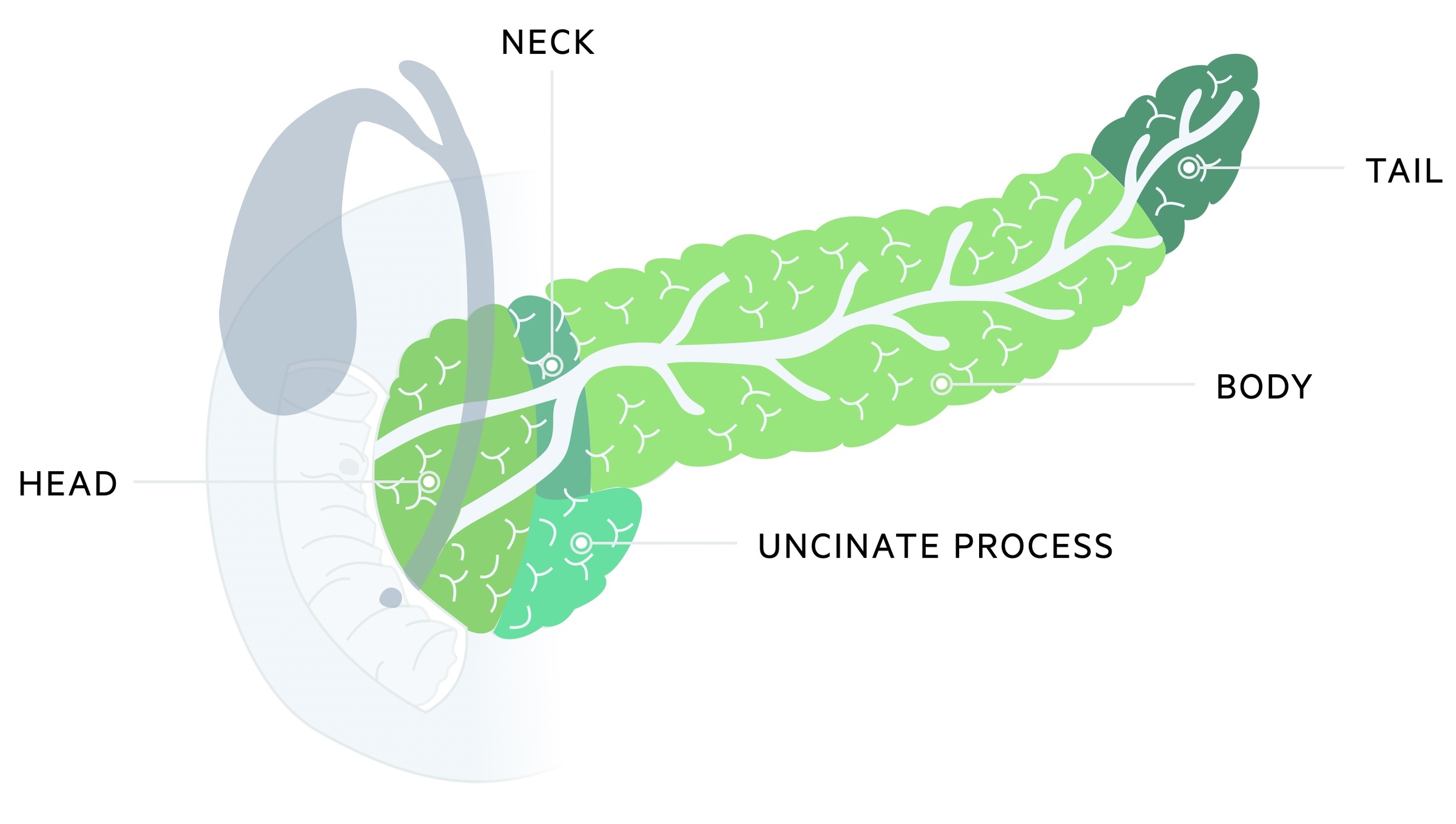

Location and spread

Around 70% of cases arise from the pancreatic head whilst 20% originate in the body/tail. The remaining cases effect the entirety of the pancreas.

Metastatic spread is common at diagnosis. Spread often affects the liver, lungs and peritoneum.

Clinical features

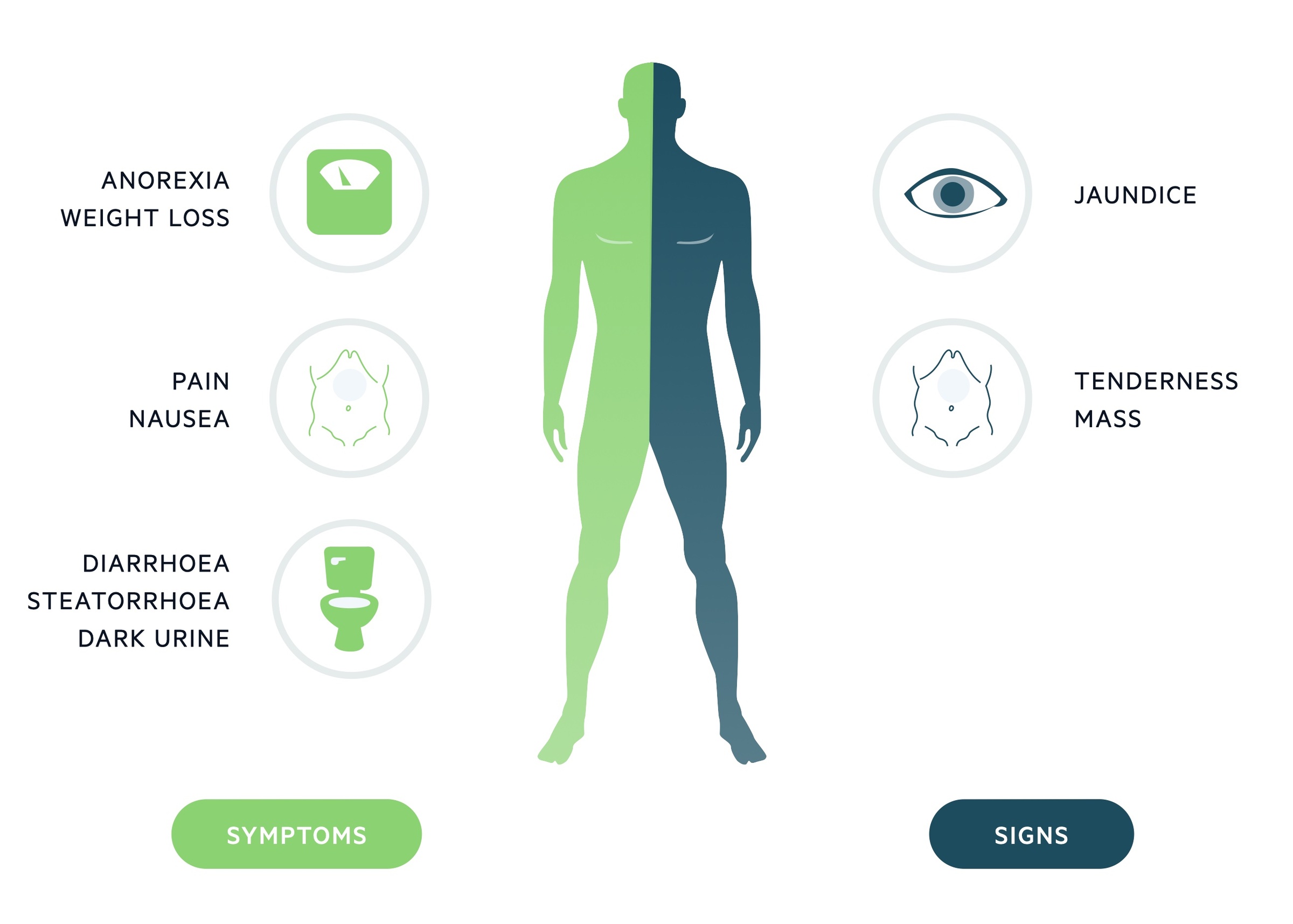

Features of pancreatic cancer include abdominal pain, jaundice and unexplained weight loss.

Pancreatic cancer may be asymptomatic for much of its development, becoming symptomatic in later stages of the disease. A significant minority of cases are diagnosed incidentally on imaging organised for unrelated reasons.

The clinical features may reflect the underlying tumour location. Tumours affecting the pancreatic head more often present with jaundice, weight loss and steatorrhoea.

The onset of diabetes can, somewhat rarely, be a sign of pancreatic cancer. However, the true nature of this relationship (causative vs result of etc) is still being established.

Symptoms

- Abdominal pain

- Jaundice

- Weight loss

- Malaise

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhoea

- Steatorrhoea

- Dark urine

- Thrombophlebitis

Signs

- Jaundice

- Epigastric mass

- Hepatomegaly

- Wasting/cachexia

- Courvoisier's law (i.e. the combination of mild jaundice and a palpable gallbladder is unlikely to be caused by gallstones, consider malignancy)

Metastatic spread

Presenting features may be the result of the spread of disease. Spread most commonly affects the liver, lungs and peritoneum.

Features include an abdominal mass, ascites and lymphadenopathy (Virchow’s node). Rarely a Sister Mary Joseph node (palpable nodule at umbilicus caused by metastatic spread of an abdominal or pelvic cancer) may be seen.

Screening

Surveillance should be offered to certain individuals at increased risk of pancreatic cancer.

UK surveillance

Surveillance is advised for patients who are at increased risk of pancreatic cancer. NICE guidance 85 (NG85): Pancreatic cancer in adults: diagnosis and management (published Feb 2018, last accessed Nov 2021), advises surveillance for those with:

- Hereditary pancreatitis and a PRSS1 mutation

- BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2 or CDKN2A (p16) mutations and one or more first-degree relatives with pancreatic cancer

- Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

NICE also recommend considering surveillance if:

- Two or more first-degree relatives with pancreatic cancer, across two or more generations

- Lynch syndrome (mismatch repair gene MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 or PMS2 mutations) and any first-degree relatives with pancreatic cancer

Surveillance generally takes the form of MRI/MRCP or EUS for those without hereditary pancreatitis and CT (pancreas protocol) for those with hereditary pancreatitis.

EUROPAC research study

The European Registry of Hereditary Pancreatitis and Familial Pancreatic Cancer (EUROPAC) is a screening study looking at pancreatic cancer in those with genetic risks.

The entry criteria, taken from the study site are:

- Families with two or more first-degree relatives (parent, sibling, offspring) with pancreatic cancer

- Families with three or more relatives with pancreatic cancer

- Families with an associated cancer syndrome and at least one case of pancreatic cancer. This includes families with a BRCA2 mutation, Familial Atypical Multiple Mole Melanoma (FAMMM) syndrome, Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC) and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

Screening may involve blood tests (fasting glucose and CA 19-9), imaging (EUS and CT) and in the future, molecular tests (samples obtained by OGD).

Referral

An urgent cancer referral for suspected pancreatic adenocarcinoma should be considered in patients > 40 years old with new-onset jaundice.

The NICE guideline (NG12): Suspected cancer: recognition and referral (published 2015, last updated Jan 2021, last accessed Nov 2021) have recommendations for urgent referral in patients with suspected pancreatic cancer. This includes patients who are > 40 years old with new-onset jaundice.

An urgent CT abdomen/pelvis (within two weeks) should be considered in patients aged > 60 years old with weight loss and any of the following features:

- Diarrhoea

- Back pain

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Constipation

- New-onset diabetes

In certain situations, it may be more appropriate to advise urgent admission via accident and emergency if the patient is acutely unwell, particularly if there are any features of biliary infection due to an obstructed biliary system.

Investigations

Depending on the presentation, the first investigations tend to be either an USS, CT or MRI.

Bloods

- FBC

- Renal function

- LFTs

- Clotting screen

- Bone profile

Vitamin D deficiency is common and may be screened for. Some centres are investigating the use of DDIMER as an indicator of metastatic disease.

Imaging

- Transabdominal US

- CT pancreas protocol

- CT chest, abdomen, pelvis

- MRI pancreas protocol: often used in those with a contraindication to CT scanning.

Special tests

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and tissue sampling: ultrasound of the pancreas can be performed via an upper GI endoscopy (camera into the stomach and duodenum). This allows both visualisation of the pancreas and sampling of suspected tumours.

- ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography may be used to visualise the biliary system, take cytology or tissue samples and relieve obstructions (e.g. stents). As discussed below, in those with potentially resectable disease and biliary obstruction there is a general preference for early surgery (as opposed to ERCP).

- CA 19-9: carbohydrate antigen 19-9 is a tumour marker indicative of pancreatic cancer. Sensitivity is approximated to be around 70-92% whilst specificity is 68-92%. As the specificity suggests, CA 19-9 may be raised for a number of other reasons both malignant (e.g. HCC, pancreatic NET) and benign (e.g. cholangitis). In people without the Lewis body group antigen, CA 19-9 is not present. High levels can be a predictor of metastatic disease. It is also used to assess response to chemotherapy and disease progression.

- Faecal elastase: this is a protease produced by the pancreatic acinar cells. In normal physiology, it is secreted into the duodenum before passing out in the stool. It is a useful measure of pancreatic insufficiency.

Biopsy & further tests

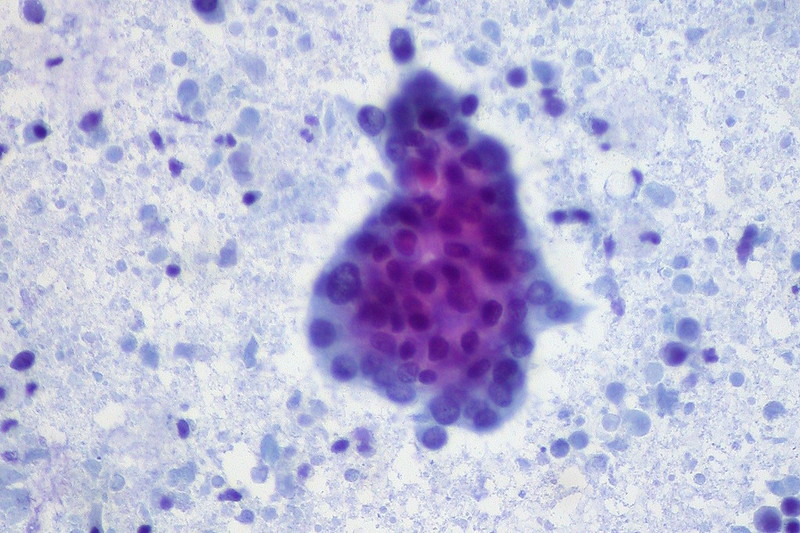

A biopsy may be used to confirm a diagnosis of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Patients will tend to have a suspicious lesion on CT, MRI or USS, but biopsy allows for confirmation. Some patients who underwent ERCP at their initial evaluation may already have histology or cytology.

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, from FNA

Image courtesy of Ed Uthman

Pre-operative biopsy confirmation is not necessarily required prior to surgery in those with resectable disease. These decisions are complex and taken by specialist MDTs. There are two main biopsy techniques:

- Endoscopic US-guided biopsy

- Percutaneous biopsy

Further investigations

- MRI liver: considered particularly in those planned for surgery.

- CT PET: considered particularly in those planned for surgery.

General management

Pain control, nutrition and emotional well-being are all key to the holistic management of patients.

The diagnosis of pancreatic cancer places a huge psychological burden on the patient and their loved ones. Input from multiple specialists is needed. Clinical nurse specialists act as a contact point, and follow the patient through their journey, providing emotional support as well as information on their condition and management.

Palliative care input may be required, even in those with potentially curative disease, for help, information and management of symptoms.

Pain

The extent of pain experienced by patients is highly variable. Simple analgesia like paracetamol may need to be complemented by opioid analgesia. In those with uncontrolled pain, coeliac plexus block is considered.

It is important to be aware some symptoms such as abdominal cramps can represent exocrine insufficiency (i.e. the pancreas is not producing sufficient digestive pancreatic juices) and require replacement.

Nutrition

All patients require nutritional assessment. Malnutrition is common and may occur for a multitude of reasons including the metabolic burden of the tumour, nausea, anorexia (i.e. a lack of appetite) and pancreatic exocrine insufficiency.

There is evidence that oral enzyme replacement improves outcomes and as such most patients are offered replacement therapy (e.g. CREON). A healthy balanced diet should be maintained and dietician referral organised where needed.

Resectable disease

When diagnosed early, resection may allow for disease remission.

The decision to treat disease as resectable should be made at specialist MDT. Around 15% are resectable at the time of diagnosis.

In general, disease is resectable (based on NCCN criteria) if:

- Metastasis: no distant disease

- Arterial: clear planes around the coeliac artery, superior mesenteric artery and hepatic artery

- Venous: no distortion of the superior mesenteric vein/portal vein

It may not be until the time of surgery that disease is found to be non-resectable. Borderline resectable disease refers to partial involvement, encasement or abutment of key vessels - this will not be covered in detail in this note.

Preoperative biliary drainage

In patients with biliary obstruction where resection is possible, surgery (and resection) is preferred to preoperative endoscopic biliary drainage. Ideally, these patients should be fast-tracked to surgery.

In those likely to have a delay in surgery or in whom it is not feasible - ERCP may be used to allow drainage.

Neoadjuvant therapy

NICE guidance 85 (NG85): Pancreatic cancer in adults: diagnosis and management (published Feb 2018, last accessed Nov 2021), advises neoadjuvant therapy is only used in the setting of a clinical trial in patients with resectable/borderline resectable disease.

When used options include chemotherapy (e.g. FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine-based regimens), chemoradiotherapy and stereotactic radiotherapy.

Surgical resection

Resection options include:

- Standard or pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure)

- Distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy (tumours of the body or tail)

- Total pancreatectomy

At the time of surgery, disease may be found to be unresctable and the primary operation abandoned. Biliary bypass or gastrojejunostomy can be performed before closing.

Splenectomy

The spleen is commonly removed in surgery for pancreatic cancer. This places the patient at increased risk of infection that is lifelong but most significant in the first 2-3 years. Patients undergoing splenectomy require (for adults):

- Vaccination: baseline haemophilus influenzae type b plus meningococcal C vaccine (Hib/MenC), meningococcal B (MenB) and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV) advised. The meningococcal ACWY conjugate vaccine may be given a month later with a second dose of MenB. Yearly influenza vaccine is recommended and PPV repeated every 5 years.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis: daily prophylaxis, advised lifelong (particularly in high-risk patients) though the first 2 years are most important. A standard regime would be phenoxymethylpenicillin 250mg BD (in absence of allergies).

Adjuvant therapy

Chemotherapy is considered as adjuvant therapy in all patients. Timing is dependent on patient factors and recovery from surgery. Regimens include:

- FOLFIRINOX (standard therapy)

- Gemcitabine and capecitabine

- Gemcitabine mono therapy

Unresectable disease

Disease not amenable to resection may be managed with chemotherapy and at times radiotherapy.

Palliative care input, particularly for pain management is important. Psychological support and counselling should be offered where appropriate or requested.

Unresectable disease (based on NCCN criteria) may be defined as:

- Metastasis: distant disease

- Arterial: invasion or encasement of the aorta. If the tumour is in the pancreatic head - more than 180º superior mesenteric artery encasement or coeliac artery abutment. If in the pancreatic body/tail - superior mesenteric artery or coeliac artery encasement greater than 180º

- Venous: Unreconstructable superior mesenteric vein/portal vein occlusion

Metastatic disease is defined as evidence of distant disease spread.

Chemotherapy

Locally advanced pancreatic cancer

Systemic combination chemotherapy is offered to those with locally advanced disease who are able to tolerate it.

Gemcitabine may be considered as an alternative in those not tolerating combination therapy.

Metastatic disease

Systemic chemotherapy is the mainstay of management. FOLFIRINOX may be given to those with an ECOG performance status of 0–1.

In those not well enough for FOLFIRINOX, gemcitabine combination therapy or gemcitabine alone may be considered.

Oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy may be used as a second-line option.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy may be used in those with unresectable disease. Use is guided by the specialist MDT and oncology. Forms include palliative radiotherapy, chemo-radiation or stereotactic radiotherapy.

Prognosis

The prognosis is related to staging at presentation, however, overall survival is poor.

Statistics for median survival vary widely depending on the study being reviewed. For pancreatic cancer overall, Cancer Research UK estimates that around 25% of patients survive one year or more. Only 7% survive for 5 years or more.

Those with the earliest stage disease (stage I) have a median survival of approximately 20 - 25 months. Those with stage IV disease (metastatic) have a median survival of approximately 4.5 months.

Last updated: May 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback