Extradural haematoma

Notes

Definition

An extradural haematoma (EDH) is a collection of blood in the extradural space, above the dura mater.

Extradural haematoma (EDH), also known as epidural haematoma, refers to a collection of blood in the extradural space between dura and skull. It is most often due to trauma and commonly associated with a skull fracture (75-95% of cases).

Aetiology

EDH is most commonly due to trauma from a direct head injury.

EDH is often life-threatening and patients may require emergency neurosurgery depending on the patient’s neurological status and size of the lesion. It is worth noting that the majority of patients with an EDH causing significant mass effect (midline shift or herniation) will likely have a reduced Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) or be comatose and therefore likely to be non-communicative and compliant with examinations.

The most common cause of EDH is trauma. This is usually in the form of a direct head injury during a fall or road traffic collision or impact with a high speed object (eg. ‘cricket ball’).

Risk factors

The risk factors associated with an EDH include:

- Mechanism of injury (fall or road traffic collision)

- Anticoagulants/antiplatelet use

- Alcohol excess

- Liver dysfunction

- Coagulopathy

Anatomy & pathophysiology

The brain is encased in three meningeal layers: the dura, arachnoid and pia mater.

In order to understand the anatomy and consequences of an extradural haematoma, we need to understand the anatomy of the meninges and the physiology of the Monro-Kellie doctrine.

Meninges

The brain is encased in three meningeal layers, which are the dura, arachnoid and pia mater (outside to inside). The pia mater is adherent to the surface of the brain and spinal cord. The subarachnoid space is found between the arachnoid and pia mater. The subdural space, a potential space, is found between the dura and arachnoid mater.

Pathophysiology

There is impact damage when an EDH forms, which causes the bleed to be potentially lethal. There is often an overlying skull fracture. EDH is most often caused by a fractured temporal or parietal bone which causes damage to the middle meningeal artery or vein. Rarely the source is the dural sinus. Blood then accumulates between the dura and the skull.

EDH tends not to cross suture lines unless a previous craniotomy or procedure has disrupted normal anatomy. Furthermore, EDH are not routinely seen in elderly patients as the dura is often adherent to the bone and therefore there is less potential space.

Monro-Kellie doctrine

The Monro-Kellie doctrine states that the skull is a closed vault and the sum of the brain parenchyma, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood is constant. It is a pressure-volume relationship. If one increases, then either or both must decrease in order to compensate.

In the case of an EDH, the presence of extra blood exerts mass effect and this can be potentially lethal as it can cause compression. Therefore the operative management involves a procedure called a decompressive craniectomy or craniotomy to relieve pressure, evacuate the blood clot and stop the bleeding.

Traumatic brain injury

EDH falls under the umbrella term of traumatic brain injury.

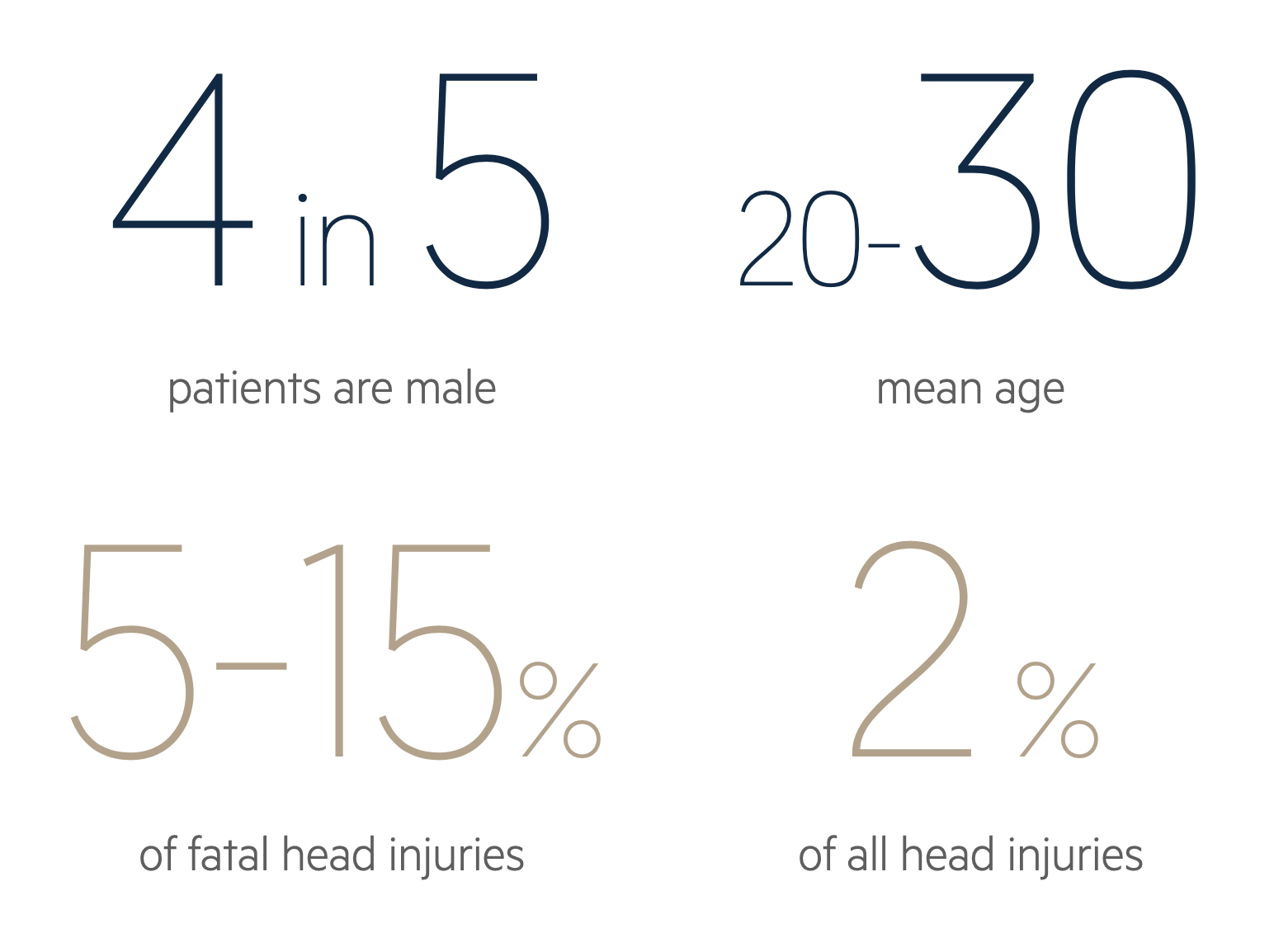

EDH is uncommon, but complicates 1-4% of traumatic head injuries.

Classification

TBI is a heterogenous term with many different ways to classify the injury (e.g. clinical severity, mechanism of injury). Traditionally, TBI is classified according to the Glasgow Coma Score (GCS).

- GCS (13-15): mild TBI

- GCS (9-12): moderate TBI

- GCS (≤ 8): severe TBI

Sequelae

Classic pathological injuries associated with TBI include:

- Skull fracture

- Extradural haematoma

- Subdural hematoma (SDH)

- Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH)

- Intraparenchymal haemorrhage

- Cerebral contusion

Clinical features

Patient usually present with a headache or decreased level of consciousness.

With an EDH, there may be a classical history of a brief loss of consciousness followed by ‘lucid interval’ then obtundation. This is not always seen. In fact, a lucid interval may occur with a subdural haematoma and therefore it is not a distinguishing feature of EDH.

If they had a significant trauma, they might already be intubated, ventilated and sedated pre-hospital. If they are alert, they may have the following features.

Symptoms

- Headache

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Seizures

- Speech difficulties

Signs

- Reduced level of consciousness (GCS)

- Altered mentation (confusion)

- Focal neurological deficit (e.g. weakness)

- Anisocoria (unequal pupils)

- Signs of herniation (fixed and dilated pupil)

- CSF leak if concurrent skull fractures

Due to the size of EDH, there is sometimes compression of the contralateral cerebral peduncle and this can cause ipsilateral weakness (right sided EDH causing right sided weakness as opposed to left). This is known as Kernohan’s phenomenon.

Clinical examination

One can only perform a neurological examination if the patient is alert enough. If the patient has a reduced GCS or is already intubated, ventilated and sedated, the only clinical correlates for brain activity are pupillary response.

NOTE: EDH are not confined to the cranial vault and can happen in the spinal cord as well.

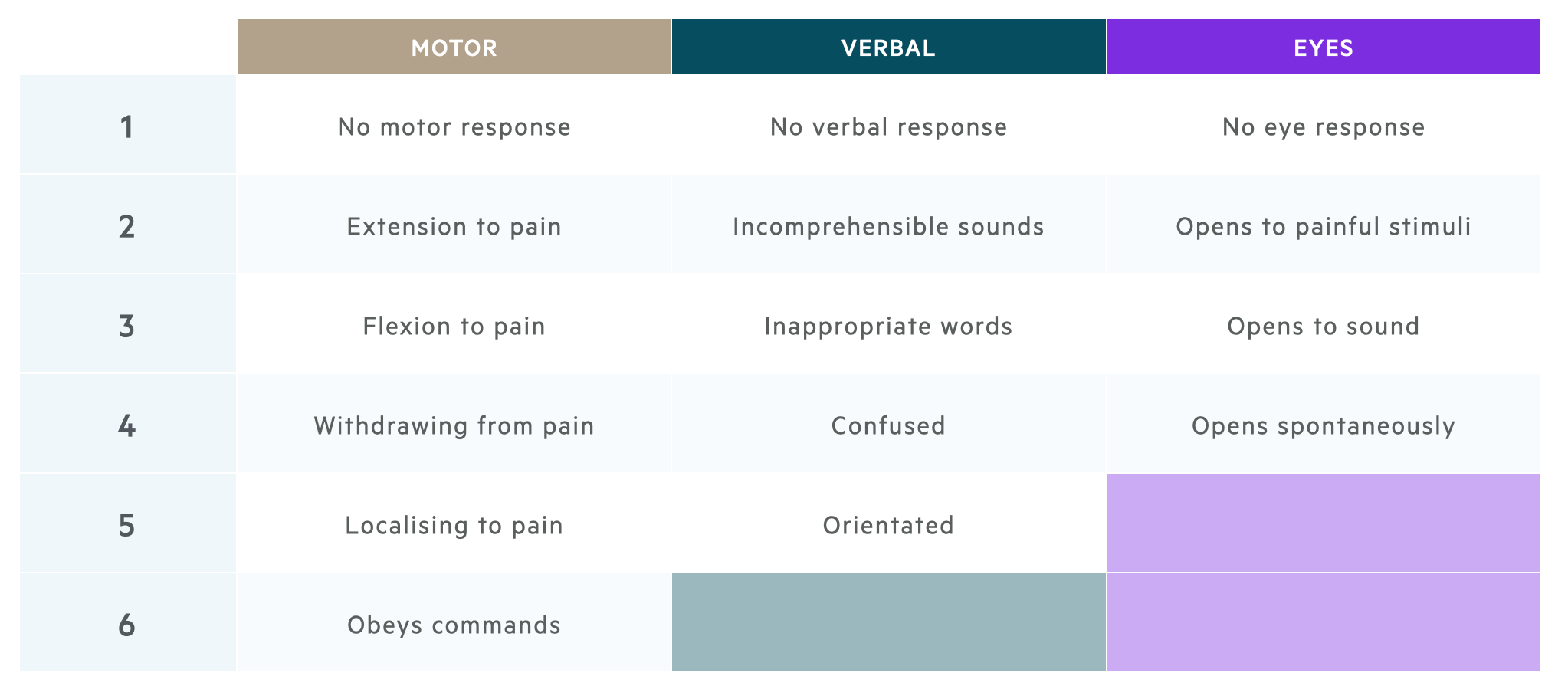

Glasgow Coma Scale

The Glasgow Coma Scale is a clinical scale used to reliably measure a person's level of consciousness after a brain injury.

It is important to be familiar with the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) which is measured from 3 to 15 and has three elements.

- Motor response (1-6)

- Verbal response (1-5)

- Eye response (1-4)

Please remember, the best possible score in each category is recorded and one has to adapt (for instance, if the patient has weakness on one side, you can assess obeying commands by asking the patient to stick out their tongue).

Diagnosis

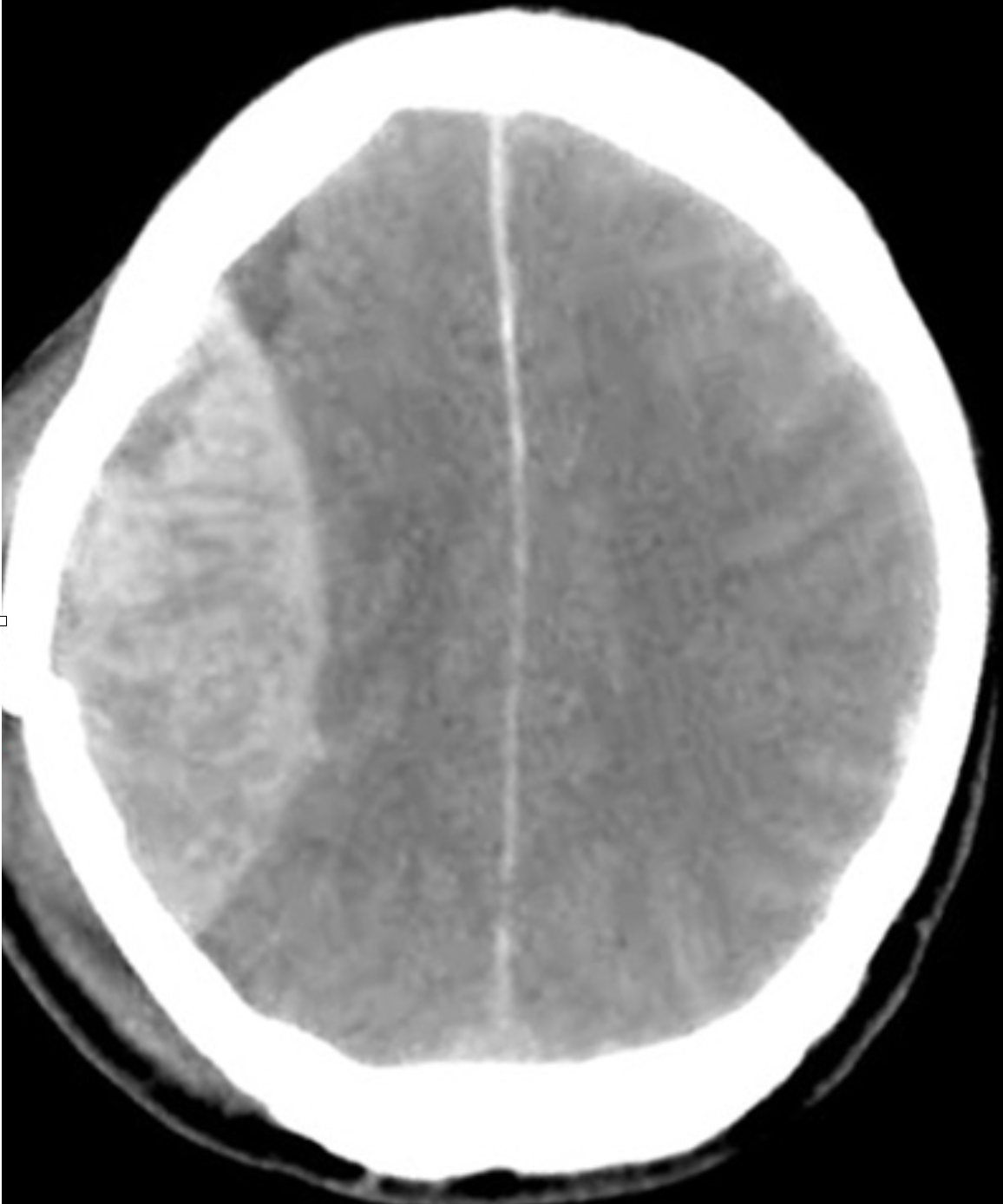

An urgent CT head is the investigation of choice for the diagnosis of EDH.

The diagnosis of an EDH is rooted in the history (e.g. trauma) and examination (e.g. reduced GCS). This being said, the principle investigation is a non-contrast CT head that will clearly show acute blood in the extradural space.

An acute EDH is readily seen on a non-contrast CT head as a high-density biconvex shape. This will usually be part of the trauma series if the patient is a ‘trauma call’. Otherwise a CT Head and CT Neck should be ordered. It is always good practice to obtain CT Neck imaging in trauma cases as there are often concurrent injuries which may require a collar and also aid neurosurgeons with operative planning.

Always inspect bony windows as there is often an overlying skull fracture.

CT head showing a right-sided extradural haematoma and associated skull fracture (note the classic biconvex shape)

Image courtesy of Hellerhoff Wikipedia Commons

Investigations

Basic investigations (e.g. bloods) are critical to the work-up of EDH because patients may require emergency surgery.

Basic investigations are critical to work-up patients with a suspected EDH to enable planning for surgery (if required), assessing for sequelae of trauma (if present) and determining the aetiology (if unknown).

Bedside

- Neurological observations: monitoring of GCS

- Blood glucose

- ECG

Bloods

- FBC - check for anaemia and thrombocytopenia

- U&E - check the electrolytes, especially sodium

- LFT - disorder or history of alcohol abuse

- Bone Profile - check for calcium

- Coagulation - check for clotting disorder

- G&S - consider if going for surgery

- Crossmatch - for blood products such as FFP, platelets and packed red blood cells

Imaging

Many patients presenting with trauma may undergo a full trauma series, which can include a CT head, neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis.

Indications for performing a trauma series will vary depending on the trauma centre, but typical indications include:

- High speed motor vehicle collision

- Non-trivial motorcycle collision

- Fall from height >2 metres

- Other concerning mechanism of injury

Management

The management of EDH has several key elements: resuscitation, initial management, medical management and surgical management.

Resuscitation

In the first instance, patients with an EDH require resuscitation. This is usually completed as part of the initial 'trauma call'.

A trauma call is an alert to the 'trauma team' to quickly assemble in response to a major trauma. The team usually consists of a team leader (accident & emergency trauma consultant) alongside an anaesthetic registrar, general surgery registrar, orthopaedic registrar, neurosurgical registrar and accident & emergency nursing team. The team will complete a rapid assessment following the mnemonic (C)ABCDE with attention paid to control of any catastrophic bleeding urgently. The patient is stabilised, undergoes urgent investigations (e.g. blood gas) and will usually have a CT trauma series. An EDH may be suspected clinically and will be detected on CT.

Stabilisation involves control of any further sources of bleeding, any coagulopathies and any acid-base disturbances. If other systems are compromised such as breathing, chest drains may be inserted or pelvic binders may be applied. It is important to remember a patient usually won’t be rushed for surgery until they are stable to be transferred to the scanner and theatre.

Initial management

Patients with an EDH can present alert or in a coma. This is assessed using the Glasgow Coma Score. A systematic ABCDE is utilised in emergency settings as discussed in resuscitation. If the patient has a low GCS (< 8) they will require airway management.

Medical management

A patient presenting with a suspected EDH should be monitored closely with neuro-observations. The expanding haematoma can be lethal and lead to death, which requires immediate operative management.

Not every EDH is amenable to surgical management and therefore polytrauma patients may be managed conservatively on an intensive care bed (level 3 as they are ventilated) with ICP management. Small extradural haematomas may be managed conservatively with interval scans and assessment of neurology. Conservative management may also be appropriate for patients too unwell for an operation due to co-morbidities or frailty.

If admitted to the intensive care unit for intubation and ventilation, neuroprotective measures may be adopted to maintain an appropriate intracranial pressure (ICP).

Neuroprotective measures:

- Normoxia (maintaining normal oxygen saturations)

- Normocarbia (carbon dioxide can be altered it ventilated)

- Normothermia (maintain normal temperature)

- Adequate sedation and paralysis

- Intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring: ensure < 22 mmHg

As part of management, collars may be loosed or the patient sat up to 30 degrees but this requires discussion with neurosurgery with due consideration to any further injuries.

ICP management:

Medically, ICP can be managed using hypertonic saline 2.7% or mannitol. Mannitol is not commonly used but may still be mentioned in guidelines. These agents do not cross the blood brain barrier and are able to draw out CSF and reduce ICP.

Seizure management:

Agents such as levetiracetam (Keppra) may be given to manage any seizure activity due to direct cortical irritation by the blood.

Surgical management

Urgent neurosurgical intervention may be warranted in the following situations:

- Significant mass affect or midline shift

- Fall in GCS

- Anisocoria

- Fixed & dilated pupils

- Persistently raised ICP

Patients require decompressive surgery to remove the blood clot and the source of the bleeding needs to be found and stopped. The skull bone may or may not be replaced. Patients are then usually managed on intensive care.

It is also worth bearing in mind that the patient may still have issues with raised ICP, especially if there were other bleeds such as traumatic subarachnoid or contusions. They may require insertion of an external ventricular drain (EVD) or lumbar drain (LD) to divert CSF away and reduce ICP. This is in keeping with the Monro-Kellie doctrine detailed above.

Complications

Patients with a good premorbid state undergoing decompressive surgery and/or intensive care admission have an excellent prognosis.

Patients with an EDH may require neurosurgical intervention. Complications associated with neurosurgery include bleeding, infection, stroke, seizures and temporary or permanent paralysis. Furthermore, they may develop systemic complications such as pneumonia (either aspiration or ventilator related), DVT/PE or urinary infections (catheter related).

These patients have to be managed in a multidisciplinary fashion in conjunction with intensive care, neurosurgery, other specialities (as required), dietitians, physiotherapists and speech and language therapists.

Last updated: July 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback