Ankle fractures

Notes

Overview

Ankle fractures are common lower limb fractures often occurring due to low-energy torsional trauma.

They affect women more than men, most commonly those aged 30-60. Ankle fractures account for around 9% of fractures presenting to accident and emergency, representing a significant portion of the trauma workload.

Treatment involves restoration of normal anatomical alignment. This may involve conservative management with a walking boot or cast, or involve surgical fixation. Attention must be payed to the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and prophylaxis given where appropriate.

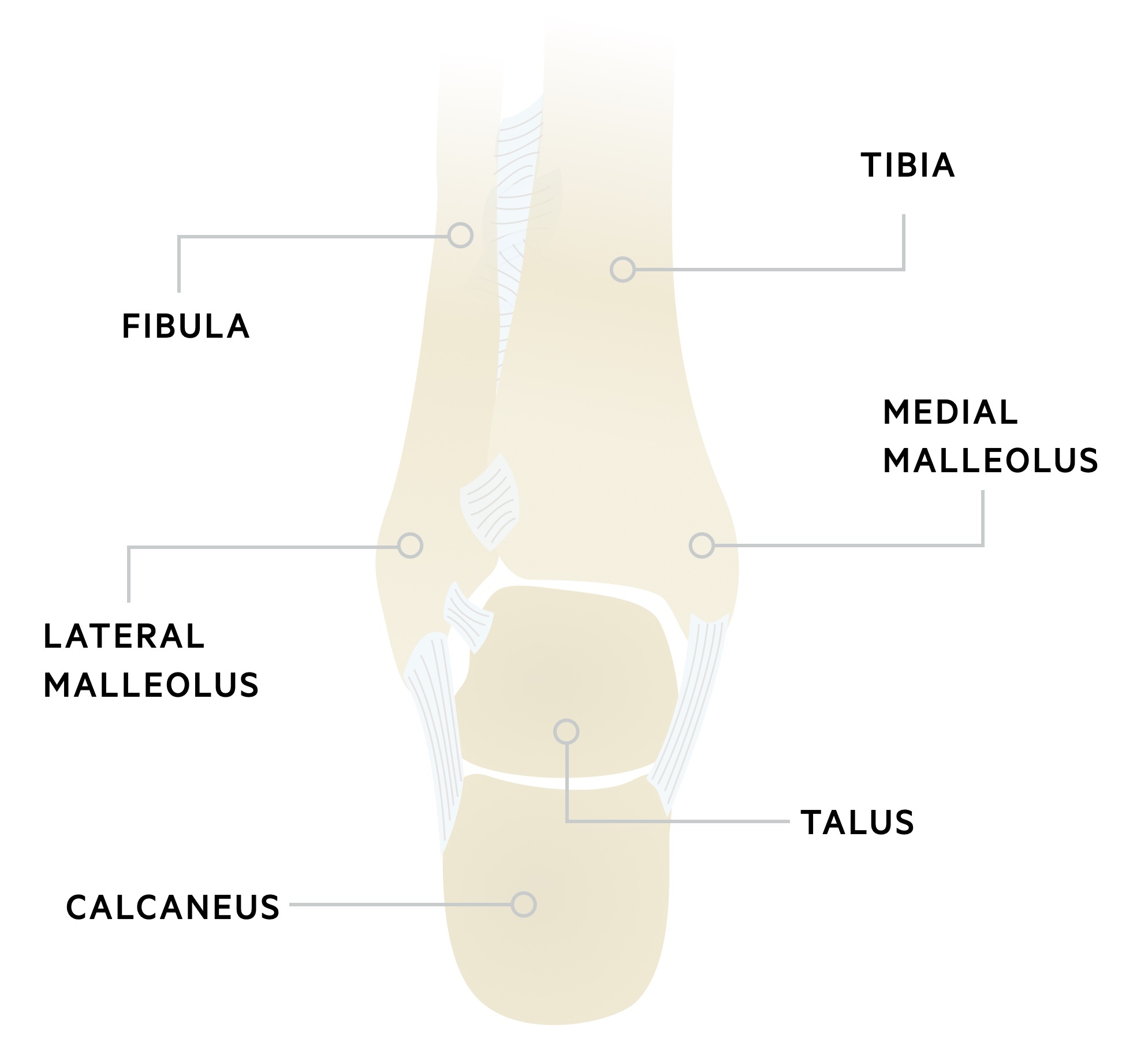

Anatomy

The ankle is a hinge joint, formed by the malleoli & talus. It is reinforced medially and laterally by collateral ligaments and stabilised by the syndesmosis.

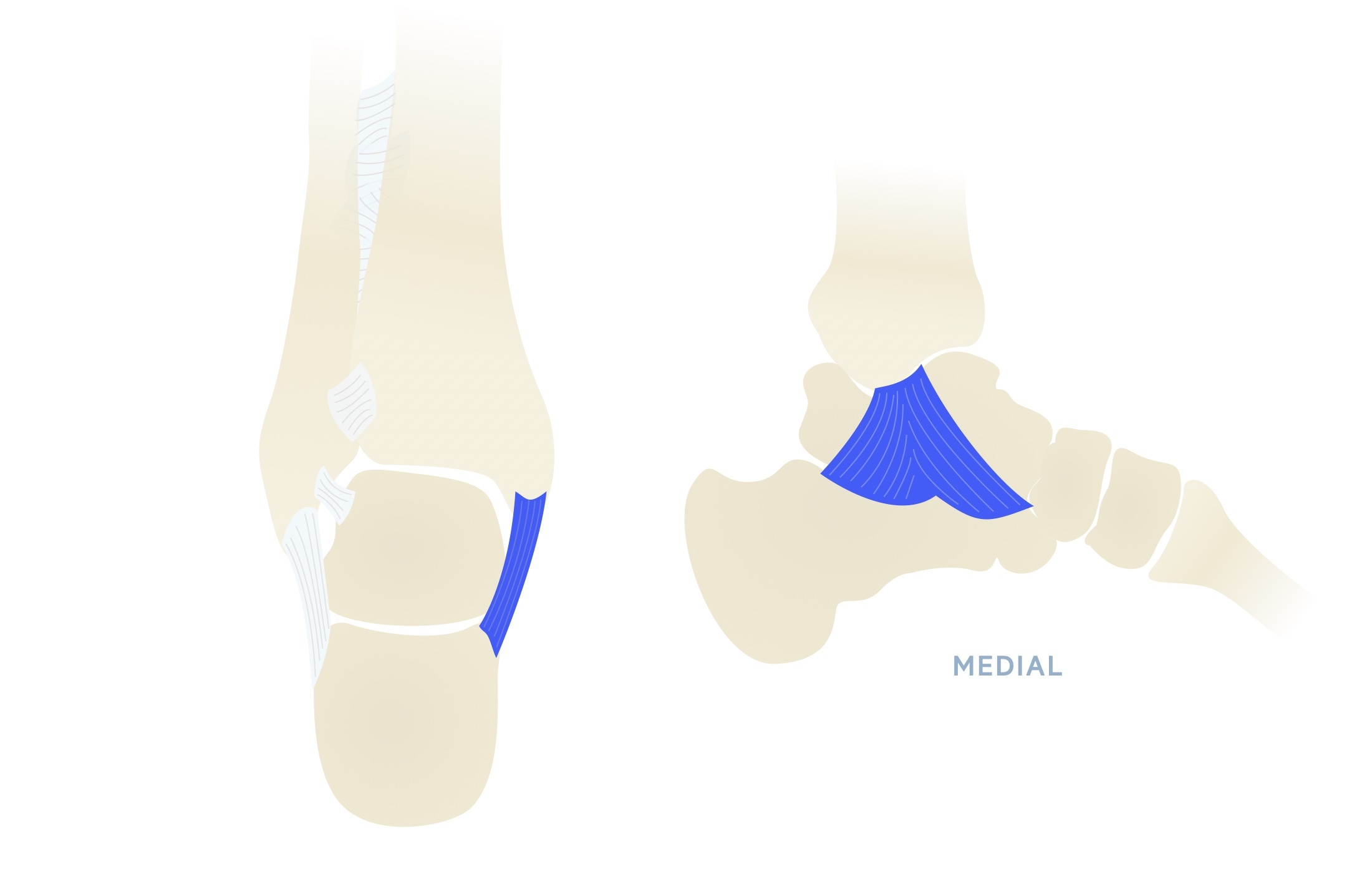

Deltoid ligament

Also known as the medial collateral ligament, it is a strong, broad, triangular ligament. It is composed of two layers: superficial and deep. The superficial fibres are divided into the tibionavicular, tibiocalcaneal and superficial posterior tibiotalar ligaments. The deep fibres are composed of the anterior tibiotalar and deep posterior tibiotalar ligament.

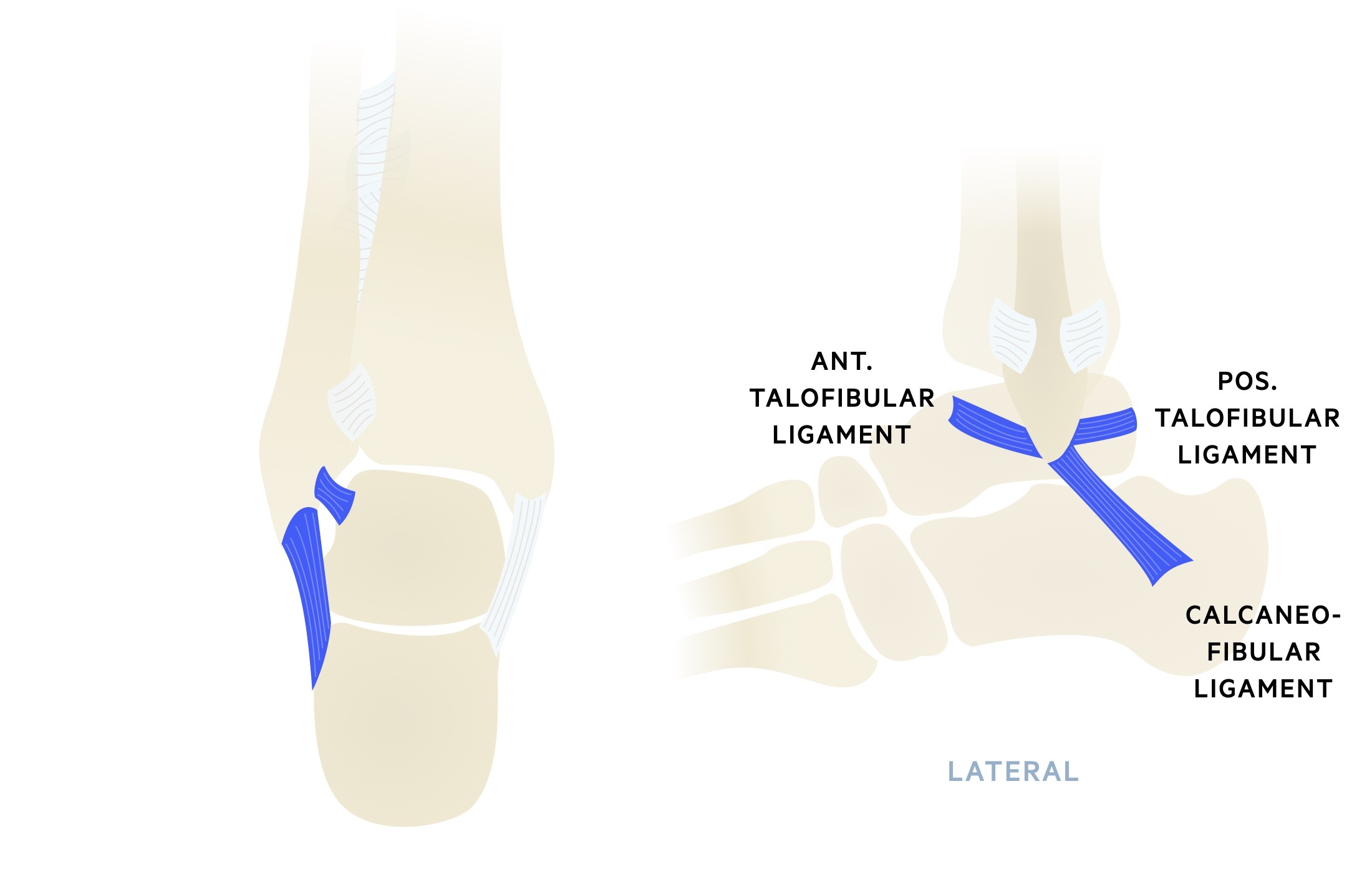

Lateral collateral ligament

The lateral collateral ligament comprises three ligaments, the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), calcaneofibular ligament & posterior talofibular ligaments (PTFL).

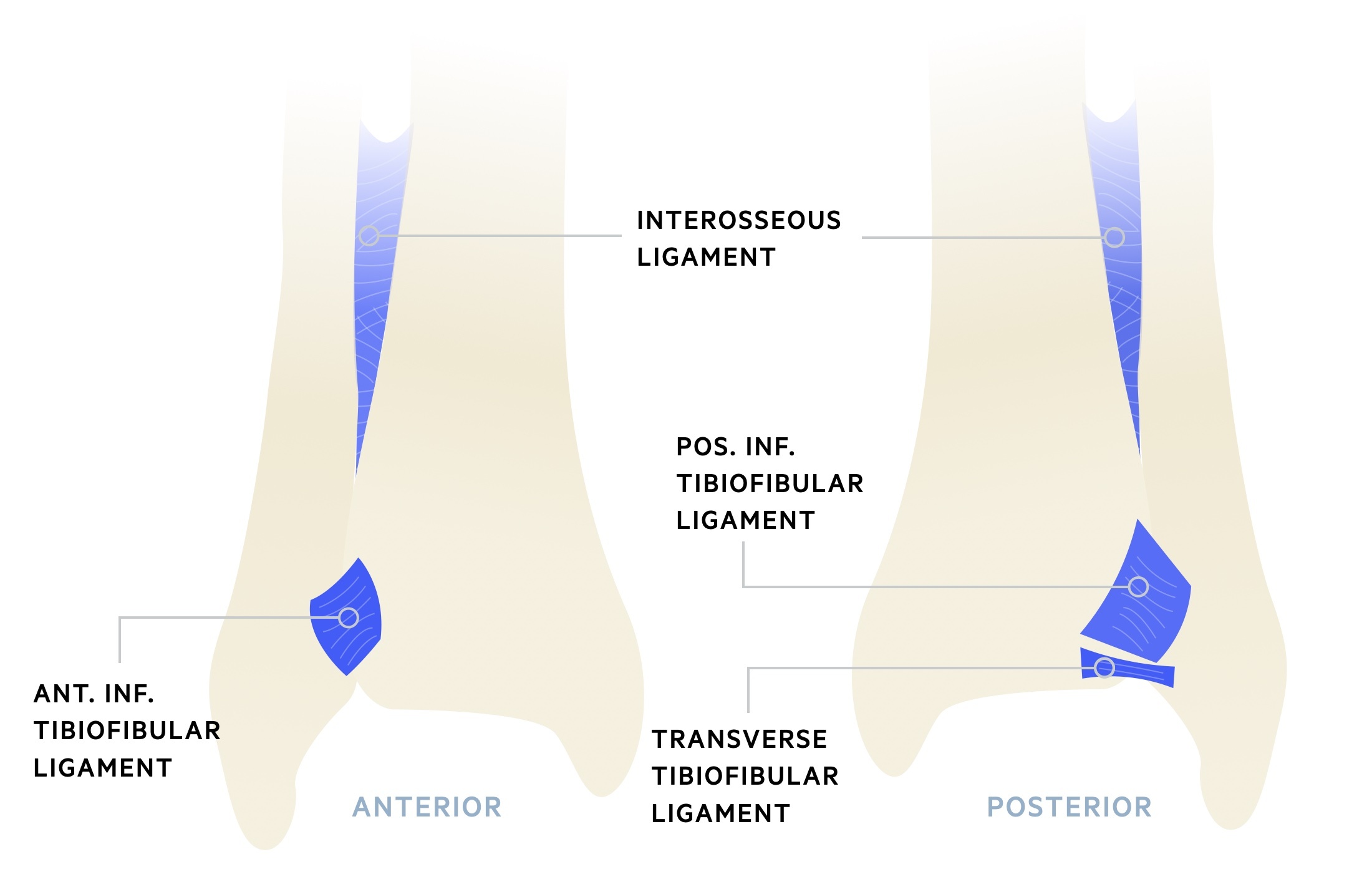

Tibiofibular syndesmosis

The tibiofibular syndesmosis complex stabilises the ankle joint. Composed of several ligaments and the interosseous membrane, it prevents the tibia & fibula from splaying during weight-bearing.

Classification

There are a number of classifications used for ankle fractures, the Weber classification is the most important to be aware of as a student.

Weber classification

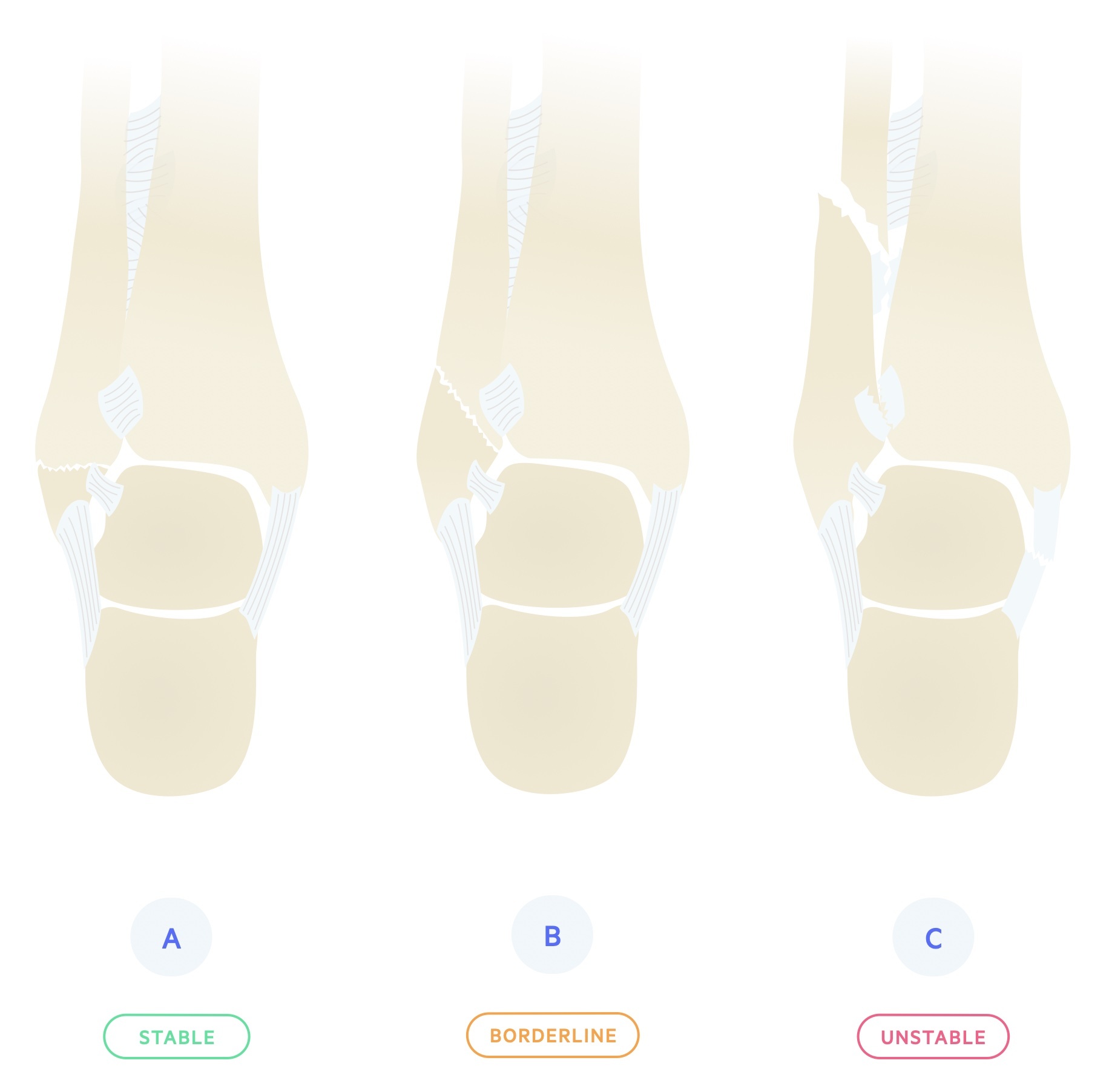

Attempts to differentiate rotational ankle fractures in relation to overall stability. Based on the level of the fibular fracture in relation to the syndesmosis (typically described with regards to the tibial plafond - essentially the ‘base’ of the tibia).

Three types A-C:

- A - Fracture below the level of the syndesmosis; typically from an inversion injury of the ankle.

- B - Fracture begins at the level of the syndesmosis and extends proximally in an oblique fashion. When accompanied by a fracture of the medial malleolus or rupture of the deltoid ligament, the ankle is considered unstable. Typically from an eversion injury of the ankle.

- C - Fractures above the syndesmosis, generally associated with syndesmotic injury. May be associated with an avulsion fracture of the medial malleolus or rupture of the deltoid ligament. Always unstable, requiring fixation.

Lauge-Hansen classification

A rather baffling classification system, based upon the mechanics of the injury. Firstly, describes the position of the foot at the time of injury and secondly the deforming force. As with Danis-Weber, provides an indication of the likely stability of the ankle.

Pott’s classification

Fractures are described in terms of the number of malleoli involved. Injuries are categorised as uni-malleolar, bi-malleolar or tri-malleolar. Although easy to use, with good clinical intra-observer reliability, the Pott’s classification fails to distinguish between stable and unstable injuries, and therefore clinically is of limited use.

Maisonneuve fracture

A Maisonneuve fracture describes a fracture of the proximal fibula combined with an unstable ankle injury.

Sometimes considered a high Weber C, should not be missed! On occasion the energy from an ankle injury will pass through the ankle and syndesmosis and exit at the proximal fibula. This implies the energy has ruptured the syndesmosis resulting in an unstable ankle.

Always check for knee / proximal fibula pain. It may also be suspected after seeing widening of the mortise without obvious fracture on ankle views.

Clinical features

Ankle fractures typically present with pain and swelling at the ankle joint.

Patients usually describe a fall with a rotational injury to the lower limb. They typically report inability or difficulty in bearing weight and pain on the affected side with a reduced range of movement. If an open injury is seen it should be managed as per BOAST guidelines.

Symptoms

- Pain

- Inability to weight bear

Signs

- Bony tenderness

- Swelling

- Deformity

Ottawa ankle rules

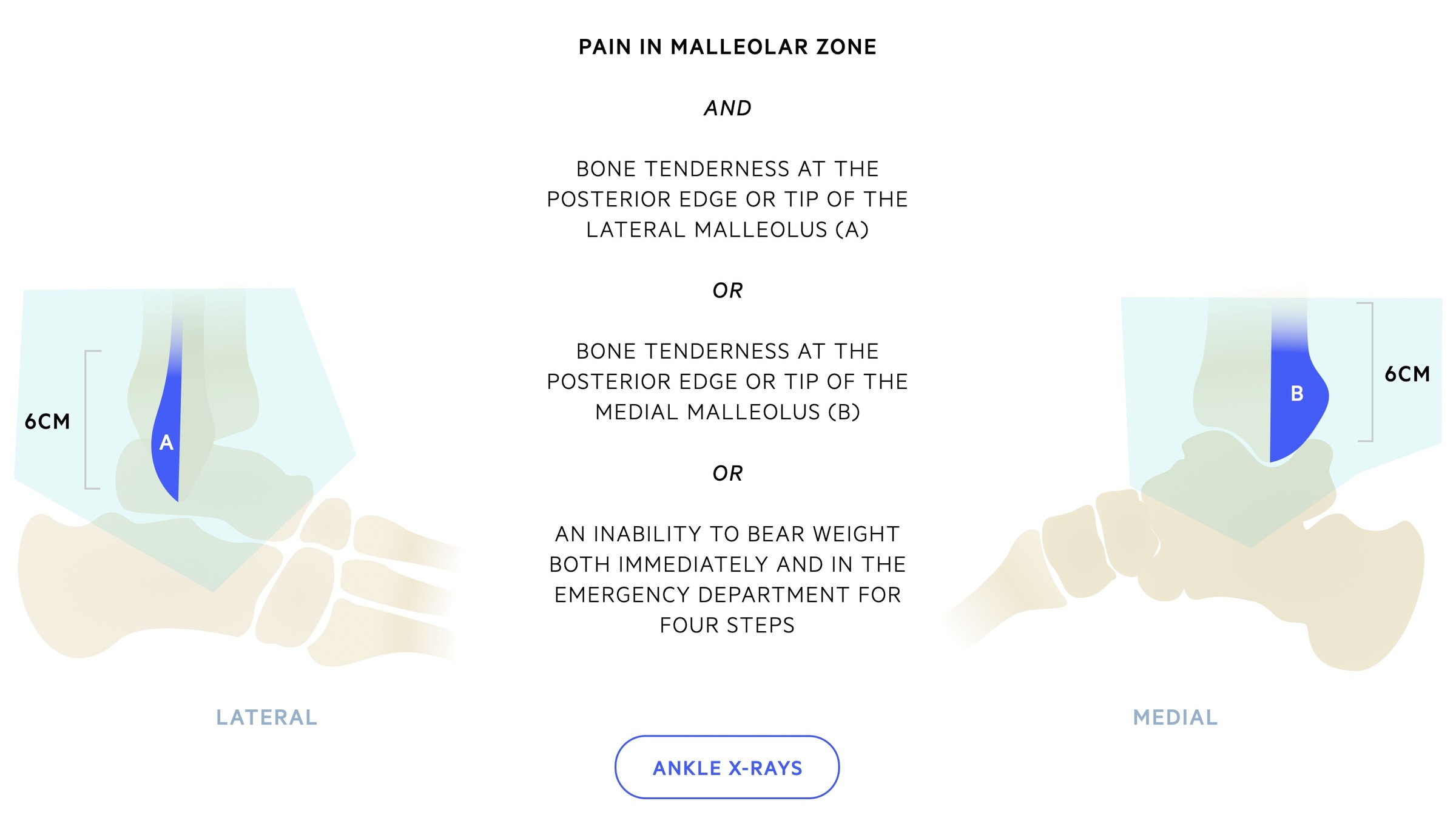

The Ottawa ankle rules help differentiate ankle injuries that require radiographic assessment from those that do not.

They state that an ankle radiograph series is only required if there is pain in the malleolar zone (highlighted turquoise in below image) and one or more of the following is found:

- Boney tenderness at the posterior edge or tip of the lateral malleolus OR

- Boney tenderness at the posterior edge or tip of the medial malleolus OR

- Inability to weight bear immediately and in the A+E department for four steps

Investigations & diagnosis

An ankle series, AP, mortise and lateral, plain radiographs are used to diagnose ankle fractures.

Bedside

- Observations

- Urine dip (if indicated on suspicion of infection)

- Pregnancy test

- ECG (if needed pre-op, or possible cardiac cause of fall)

Bloods

- FBC

- U&Es

- CRP

- Clotting screen

Imaging

- XR ankle: An ankle series consisting of a AP, mortise and true lateral. The mortise view allows us to assess for talar shift. Talar shift refers to the widening of medial clear space and is indicative of an unstable injury with damage to the syndesmosis. It may not be evident on non-weight bearing films.

- XR fibula/tibia: Indicated when there is suspicion of Maisonneuve injury.

- CT ankle: Helps better define fracture pattern, should be obtained in complex ankle fractures, particularly those involving the posterior malleolus.

Management

Management of ankle fractures may involve a walking boot, cast or surgical fixation.

A thorough history identifying the mechanism of injury is recorded. Clinical findings, a complete neurovascular assessment and skin integrity should be documented for every patient.

The management of open fractures is not covered here.

Weber A fractures

Weber A fractures are generally stable. Surgical management is rarely indicated and they can be discharged from A&E in a walking boot with analgesia. Elevation and iceing at home can help with pain and swelling.

All patients should be followed up in fracture clinic for re-assessment and to confirm a healing injury. Those unable to mobilise safely with a walking boot may require admission for PT/OT assessment.

Unstable injuries

- Analgesia - Ankle fractures are painful injuries and analgesia should be given as soon as is possible and safe. Take into account allergies, age, renal function, weight, current medications and co-morbidities.

- Reduce and cast - In those with clinically deformed ankles - reduction and splinting should be performed urgently, though generally radiographs should be taken prior unless there will be delay. Reductions of dislocated ankles should be completed in Resus with appropriate analgesia and sedation (e.g. Ketamine) and airway cover. If no reduction is required or once reduction is complete the patient should be placed in a below knee backslab.

- Re-assess - Imaging should be repeated to confirm reduction and positioning. After any reduction or casting repeat a neurovascular assessment.

- Elevate - All patients should be encouraged to keep the affected limb elevated at rest.

- Referral - Patients should be referred to orthopaedics for review and discussion at the trauma meeting. Generally they should be kept NBM until review.

Many Weber B and most Weber C will benefit from surgical fixation. This decision is made by the orthopaedic team taking into account the fracture pattern, patient co-morbidities and wishes. Rarely external fixation may be needed in the presence of gross swelling.

Following surgical fixation the patient will normally be placed in a below knee cast - the decision on weight bearing will be made by the operating surgeon. Follow up is in fracture clinic.

In patients who are elderly or co-morbid (e.g. diabetes mellitus, peripheral neuropathy) closed contact casting (CCC) should be considered for definitive management. Complications associated with surgery (e.g. infection) are eliminated though there appears to be a higher risk of mal-union with CCC.

VTE prophylaxis

There is an increased risk of VTE in lower limb fractures - particularly if the limb is immobilised in a cast.

Follow local guidelines and prescribe VTE prophylaxis where appropriate. Patients should also be informed of the risk, signs and symptoms to be aware of and to seek medical attention immediately if they occur (ideally also given a patient information leaflet).

Last updated: October 2021

Further reading

- BOAST Guidelines: The management of ankle fractures

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback