Osteomyelitis

Notes

Overview

Osteomyelitis refers to infection of the bone.

It is a serious infection that benefits from prompt recognition and treatment. Risk factors include diabetes, old age, peripheral vascular disease and immunocompromise. It may occur for many reasons including open fractures, skin ulcers, surgery (and prosthesis) and haematogenous spread of bacteria.

Staphylococcus aureus is the most commonly identified infecting organism. Treatment involves long courses of antibiotics (normally a minimum of 4-6 weeks) and at times surgical debridement.

The focus of this note will be osteomyelitis in adult patients.

Causative organisms

Staphylococcus aureus is the most common cause of osteomyelitis.

- Staphylococcus aureus: A gram-positive cocci. Includes MRSA (Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus) a penicillin resistant organism.

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A gram-negative rod. More commonly seen in IV drug users.

- Salmonella spp.: Gram-negative rods. Most commonly seen in patients with sickle cell anaemia.

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae: A gram-negative diplococci. Seen in the sexually active where rarely may cause a disseminated infection.

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Acid fast bacilli. May cause osteomyelitis - characteristically in Pott’s disease (TB affecting the spine).

- Polymicrobial: More commonly seen in those with ulcers secondary to vascular disease, neuropathy and diabetes.

There are many, many other causative pathogens that may be isolated or suspected. Relatively rarely fungal species can cause osteomyelitis.

Pathogenesis

Osteomyelitis may be caused by the haematogenous spread or non-haematogenous spread of pathogens to bone.

Infection of the bone is uncommon. Numerous mechanisms exist to protect it from becoming infected. Importantly our immune system acts to rid the body of pathogens and our skin and soft tissues act as a physical barrier to infection.

Haematogenous spread

Haematogenous spread refers to the spread of a pathogen via the blood. Risk factors for such infections include:

- Indwelling intravascular catheter (e.g. Hickman line)

- Haemodialysis

- Endocarditis

- IV drug use

Osteomyelitis occurring secondary to haematogenous spread in adults most commonly affects the axial skeleton, primarily the vertebral bones. After the vertebral bones the next most frequently affected sites are other axial bones like the sternum and pelvis. Less commonly (in adults) long-bone osteomyelitis is seen - which when affecting the metaphysis may lead to septic arthritis.

Staphylococcus aureus is the most commonly identified organism. In the IVDU population a different microbial pattern is seen with Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated more frequently.

Non-haematogenous spread

Non-haematogenous spread occurs due to breakdown or removal of the normal protective barriers of skin and soft tissue or spread from a contiguous focus of infection. This may occur for a number of reasons:

- Skin ulcers

- Trauma

- Surgery (especially when foreign material is placed)

- Animal / insect bites

Patients with peripheral vascular disease, neuropathy, diabetes, reduced mobility or nutritional deficiency are at greater risk of developing skin ulcers and having poor healing following surgery. Again Staphylococcus aureus is often isolated but in those with foot ulcers secondary to diabetes and peripheral vascular disease polymicrobial infection is often seen.

Clinical features

Osteomyelitis may present with fever, pain and signs of local inflammation.

Symptoms

- Fever

- Pain

- Overlying redness

- Swelling

- Malaise

Signs

- Erythema

- Swelling

- Evidence of previous surgery or trauma

- Tenderness

- Discharging sinus

- Ulcers / skin breaks

Clinical features may reflect aetiology - examples include surgical scar, healing wound or a foot ulcer. In those with haematogenous spread from a central source further signs may be seen. For example osteomyelitis can result from infective endocarditis, if this is suspected listen to the heart for a murmur and check for peripheral and ocular signs of endocarditis. Always consider the underlying cause and evaluate for possible features.

Investigations

Blood tests will normally reveal a non-specific rise in inflammatory markers.

A fever, often low-grade, is common. It may be accompanied with a tachycardia and rarely features severe sepsis. Blood tests will typically show elevated WCC, CRP and ESR.

Sending appropriate microbiology samples early and where possible prior to antibiotics is essential. Patients who aren’t known to be diabetic should be screened (a bedside blood sugar and a HbA1c).

Bedside

- Vital signs

- Blood sugar

- Urine dip

Bloods

- FBC

- UE

- CRP

- LFT

- ESR

- HbA1c

Microbiology

- Urine MSU

- Blood cultures

- Wound swab

- Bone culture

Further investigations may be indicated depending on the exact clinical context. For example where infective endocarditis is suspected, an echocardiogram will typically be ordered.

Imaging

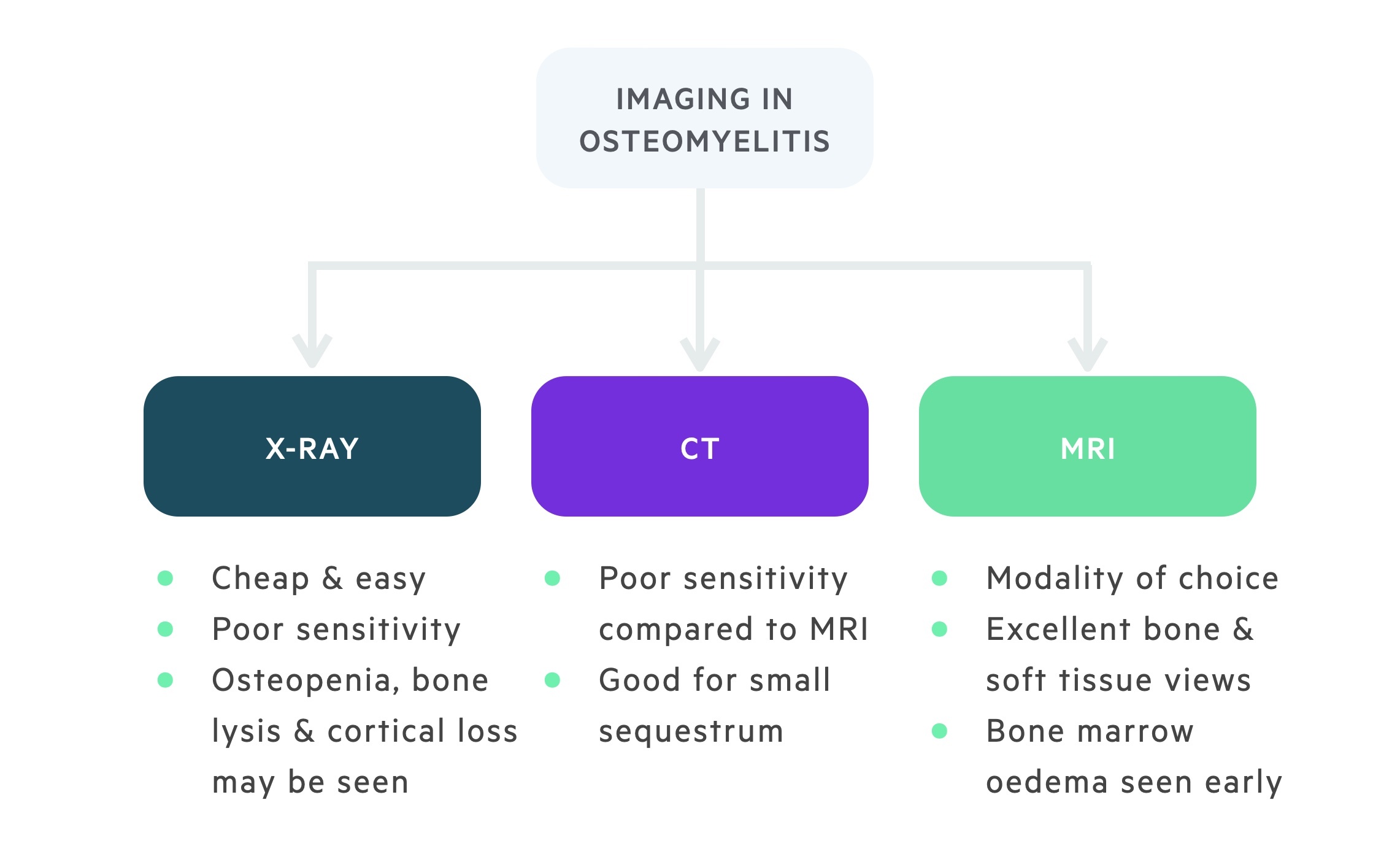

Osteomyelitis is normally diagnosed on MRI imaging.

There are a number of terms that may be referred to in imaging reports for osteomyelitis. These refer to radiological evidence of underlying pathological findings:

Sequestrum: Refers to a dead piece of devitalised bone that has been separated (i.e. sequestered) due to necrosis from the surrounding bone.

Involucrum: New growth of periosteal bone around a sequestrum.

Cloaca: An opening in an involuvcrum that allows the internal necrotic bone and pus to discharge out.

X-ray

An x-ray of the suspected area should be taken, in long bones including adjacent joints. Plain film radiograph is not particularly sensitive for osteomyelitis, which needs to be sufficiently advanced, but is an appropriate first step. The bone may show signs of:

- Local osteopenia

- Areas of bone lysis

- Cortical loss

- Periosteal reaction.

In more advanced disease sequestrum and involucrum may be seen. Changes can also be seen to surrounding tissues with evidence of swelling and adjacent joints which may show signs of a ‘sympathetic’ effusion.

CT

Though CT is excellent at defining bone and small sequestrum and involucrum it is significantly less sensitive than MRI for osteomyelitis. It is often more readily available and may be used to aid surgical planning but generally MRI is preferred.

MRI

MRI is the imaging modality of choice. It offers excellent visualisation of the both bone and the surrounding soft tissue. Bone marrow oedema may be seen very early on in the course of osteomyelitis.

Cortical sequestra may be difficult to pick up and nearby metalwork (from prosthesis) can significantly impact the quality of images.

Other

There are a myriad of other imaging options if diagnostic uncertainty remains. These include FDG-PET and Technetium-99m bone scintigraphy.

Management

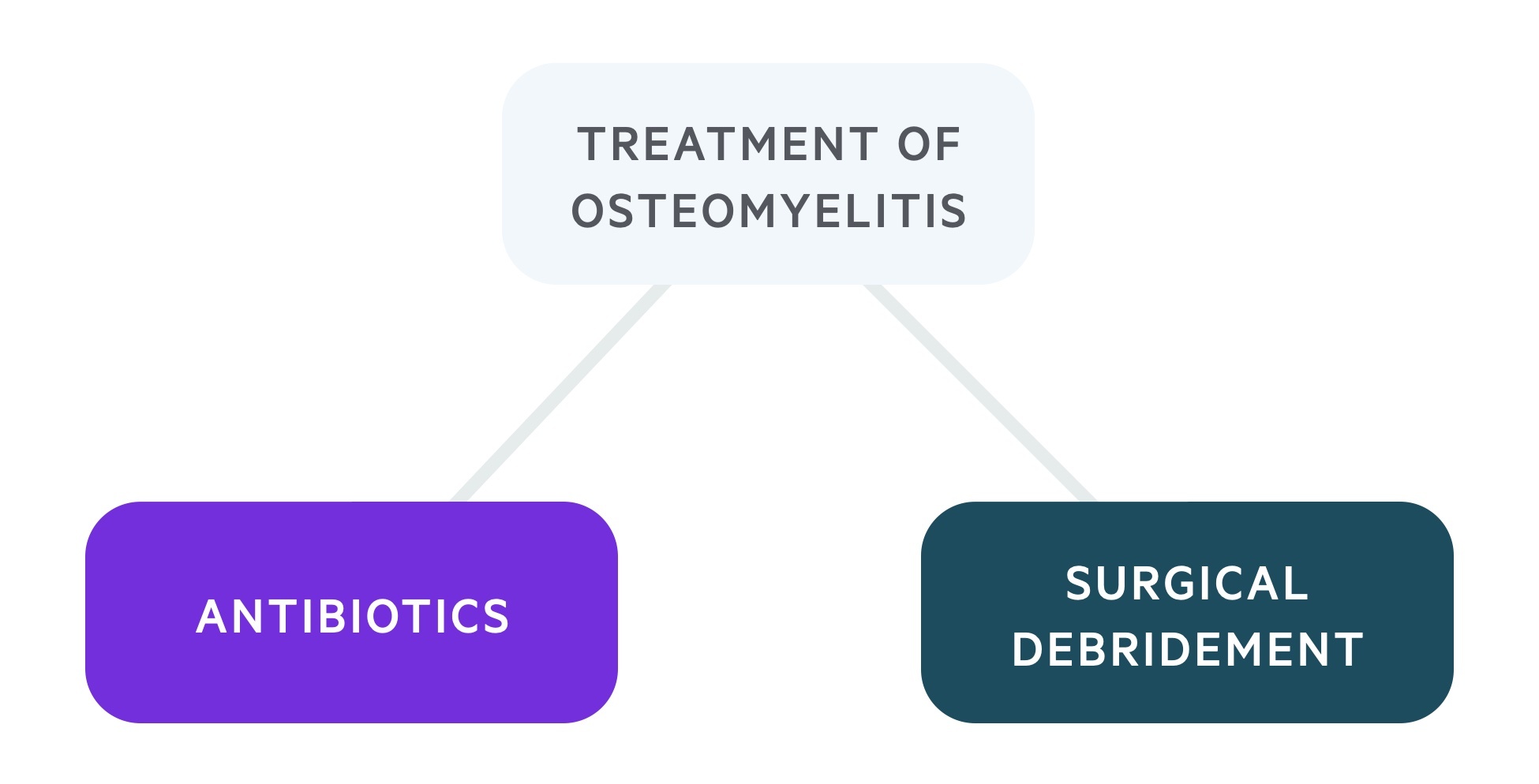

Antibiotics +/- surgical debridement forms the mainstay of management.

The management of osteomyelitis is complex. Here we will aim to give a general idea of the important principles. Optimal management is only achieved through close engagement between the patient and members of the multi-disciplinary team looking after them. This may include orthopaedic, plastic and vascular surgeons, radiologists, microbiologists, endocrinologists, diabetic specialist nurses and many others.

There are two main aspects to management, intravenous antibiotics and surgical debridement (when indicated). Whenever possible antibiotics should be held until bone cultures (or at least blood cultures and any relevant tissue swabs) have been taken. Antibiotic courses tend to be a minimum of 4-6 weeks and are guided by microbiology. Where possible and appropriate these can be administered as an outpatient.

Attention must also be paid to symptomatic relief. Pain may be substantial (or absent in cases with significant neuropathy) and appropriate analgesia should be prescribed. Patients with vertebral osteomyelitis may receive symptomatic relief from back braces.

Antibiotics

As explained above wherever possible antibiotics should be held until bone cultures (or at least blood cultures and any relevant tissue swabs) have been taken.

Empiric regimens should be guided by microbiology, based on the suspected organism and updated when (or if) positive culture results are returned. An example empirical regimen would be once-daily ceftriaxone and vancomycin. This offers good coverage for S. aureus with the vancomycin active against MRSA.

The length of the course is dependent on many factors. Patients will require regular repeat blood tests to monitor inflammatory markers and may need repeat imaging.

Surgery

There are a number of indications for surgery or intervention. Surgical debridement is more commonly indicated in non-haematogenous spread osteomyelitis, although acute antibiotic therapy may be trialled first.

In many cases of haematogenous spread osteomyelitis, which in adults most commonly affects the vertebrae, an attempt will be made to treat with antibiotics first. Indications for surgery include:

- Failure to respond to antibiotic therapy

- Formation of discrete abscess

- Neurological deficit (vertebral osteomyelitis)

If surgical metalwork is present, its removal must be considered. These are not simple decisions and should be made by a senior orthopaedic/plastic surgeon.

Last updated: June 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback