Tibial plateau fractures

Notes

Introduction

Tibial plateau fractures are due to high-energy trauma in the young and low-energy falls in the elderly.

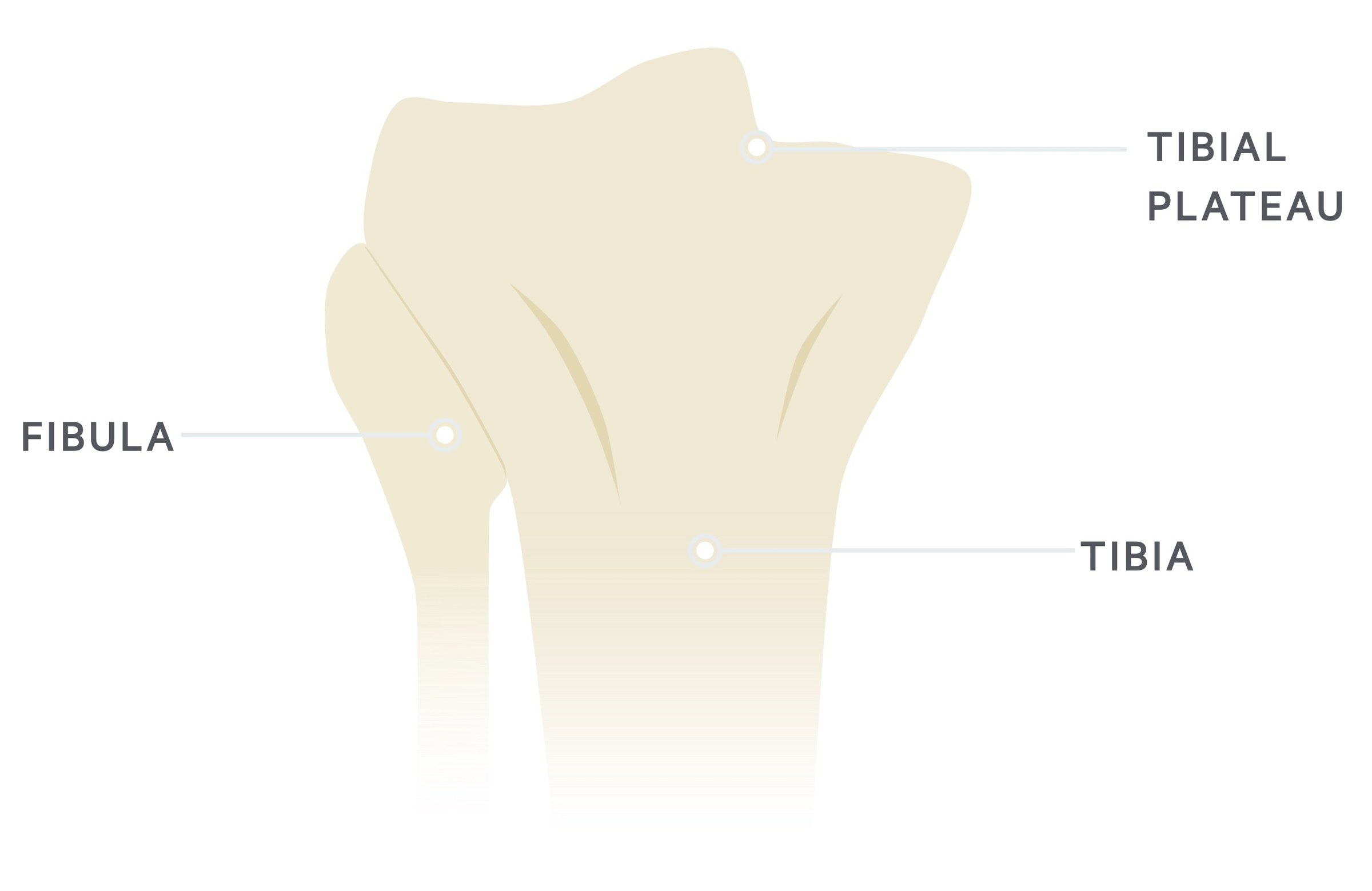

The tibial plateau refers to the proximal articular surface of the tibia, which forms the knee joint with the femur.

Tibial plateau fractures have a bimodal distribution, classically presenting in males in their 40s and females in their 70s. The incidence of these fractures is around 10.3 per 100,000 annually.

Aetiology

Tibial plateau fractures occur secondary to traumatic injuries

Mechanisms

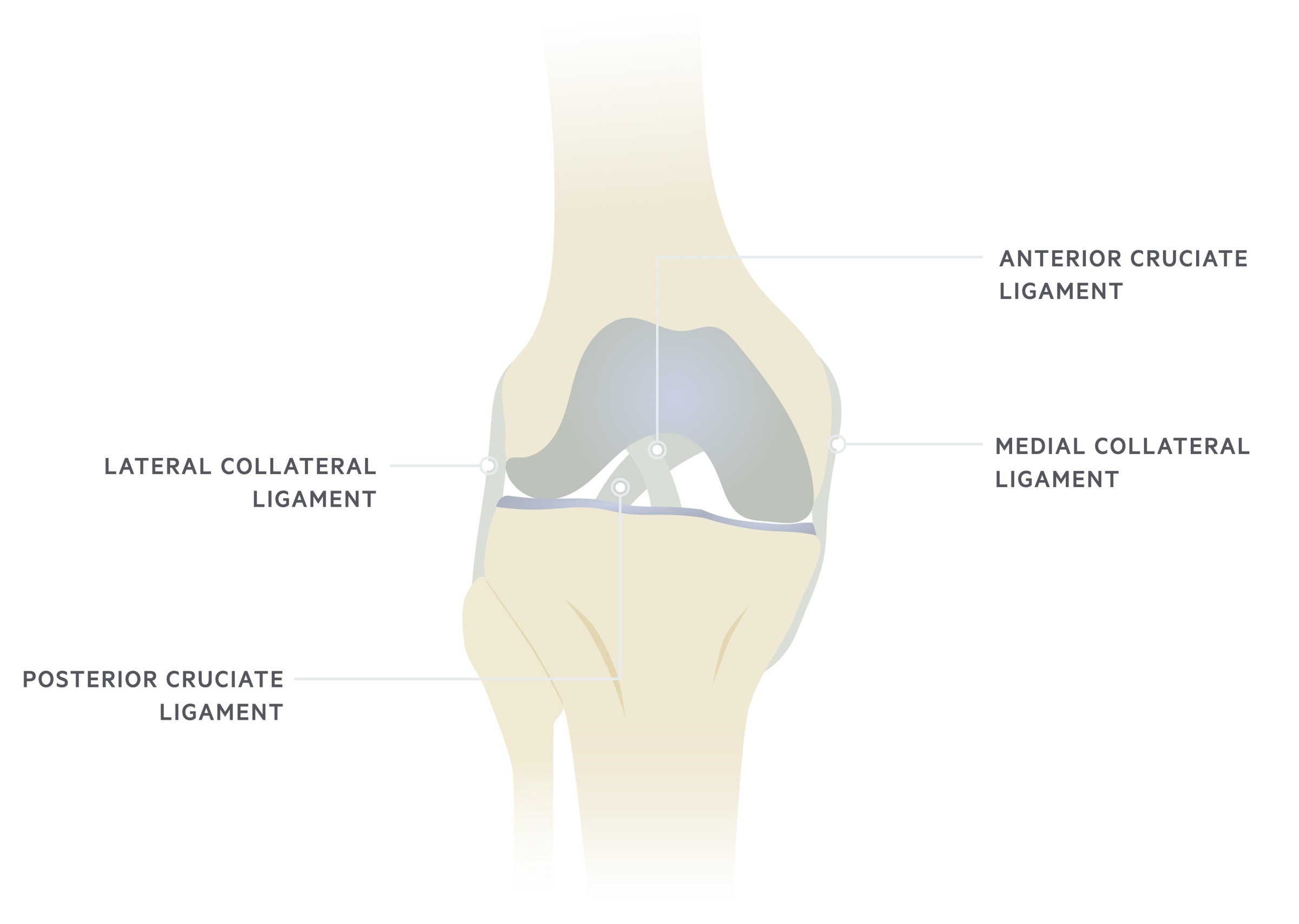

Fracture of the tibial plateau can arise from a valgus force, which describes an outside force pushing the knee inwards along a coronal plane. Alternatively, a fracture can arise from a varus force, which describes an inside force pushing the knee outwards along a coronal plane.

Importantly, high-energy mechanisms leading to a tibia plateau fracture may be associated with significant soft tissue injuries. This includes open fractures, ligamentous injury and vascular damage. In the elderly, low-energy mechanisms leading to fracture usually suggest insufficiency fractures due to osteoporosis.

Fracture types

The medial tibial plateau bears 60% of the load through the knee. The medial condyle is generally larger, stronger and transmits more weight compared to the lateral condyle. The lateral tibial condyle is convex in shape, compared to the concave medial side.

A unicondylar fracture refers to a fracture of one of the condyles, the lateral condyle is more frequently affected. A bicondylar fracture refers to a fracture of both condyles.

Aspects of the anatomy of the tibial plateau can affect the response to a fracture, these include:

- Muscular attachments: the large muscular attachments on the tibial plateau can contribute to fragment displacement following trauma.

- Joint surface: the incongruent joint surface increases the risk of post-traumatic arthritis.

- Soft tissue: injuries to the surrounding soft tissue can contribute to joint instability.

Clinical features

In acute trauma, it is often too painful to examine the knee joint’s full range of motion.

As with any trauma, features of pain, swelling, reduced mobility and deformity may be present. It is important to provide the patient with adequate analgesia to allow assessment and to take a clear history as to the mechanism of injury (a collateral history may be required from a relative or bystander).

Features include:

- Pain

- Swelling: typically due to marked haemarthrosis (blood within the joint) and soft tissue swelling. It is important to ensure muscular compartments are soft on palpation during examination

- Reduced mobility

- Deformity: may be open fracture, it is important to inspect the leg circumferentially

- Neurovascular supply: essential to ensure the leg is well perfused and sensation remains intact.

Imaging

X-rays are typically diagnostic, CT scans have a role in surgical planning.

In trauma, if fractures are suspected they should be confirmed with appropriate radiological investigations.

X-rays allow an initial diagnosis, but more detailed cross-sectional imaging (i.e. CT, MRI) may be needed to exclude complications and for surgical planning.

Imaging options include:

- Plain film radiograph of knee: get anterior-posterior (AP), lateral and plateau views*. Look out for lipohaemoarthrosis (fat and fluid within the joint) on the lateral view, which suggests an intra-articular fracture. Plain X-ray may miss subtle fractures, where sufficient suspicion exists a CT or MRI should be arranged.

- Computed tomography of knee: allows better visualisation of articular depression and comminution (i.e. fragments). Also used when suspicion remains after a normal-appearing radiograph. Important for surgical planning.

- CT Angiography: allows visualisation of arterial supply to lower limbs. Undertaken if there are any concerns of vascular injury (e.g. damage to the popliteal artery).

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): useful in diagnosing meniscal and ligamentous injury.

*NOTE: A plateau view refers to a 10 degree caudal tilt to compensate for the anatomical 10 degree posterior tibial slope.

Schatzker classification

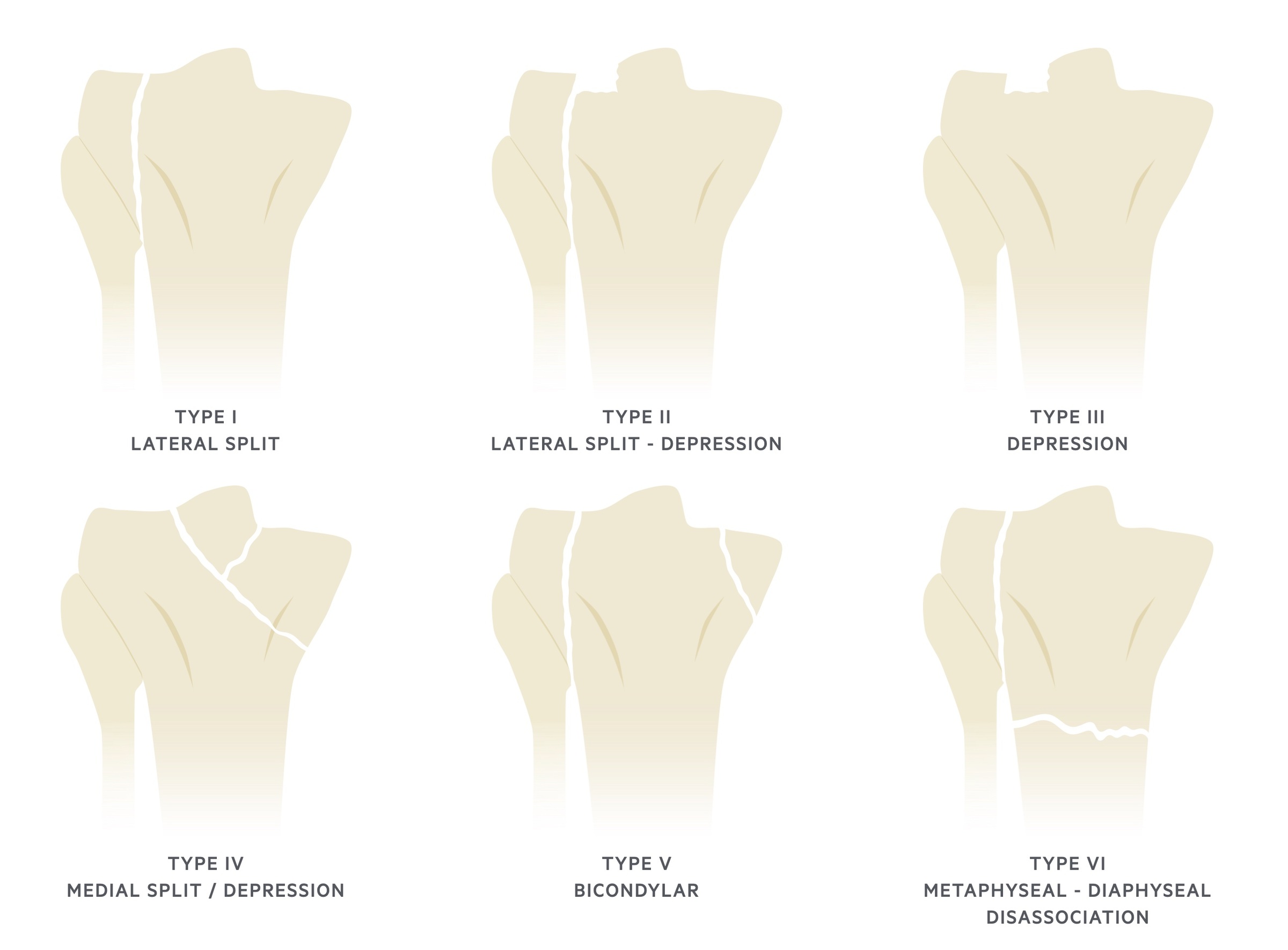

The Schatzker classification is commonly used to describe tibial plateau fractures.

The Schatzker classification is split into six types. Each increase in the category is generally indicative of higher-impact trauma and increased morbidity.

Type I: Wedge-shaped lateral split fracture.

Type II: Wedge-shaped lateral split fracture with depression of the lateral tibial plateau. Often associated with injuries to MCL or medial meniscus.

Type III: Pure depression of the lateral tibial plateau.

Type IV: Medial plateau fracture with split or depression.

Type V: Bicondylar fracture.

Type VI: Metaphyseal-diaphyseal disassociation. Often extensive soft tissue injury and fractures may be open, significantly increased risk of compartment syndrome.

Management

The principle of management is to restore joint stability.

The management of a tibial plateau fracture, like most acute fractures, involves analagesia and acute stabilisation of the joint followed by non-operative (conservative) or operative management.

Acute management

Consider the mechanism of injury, presenting state and other associated injuries - is a trauma call required? Complete a head-to-toe assessment in all patients.

Patients should be given appropriate analgesia placed in a brace or above knee plaster of Paris (POP) backslab. They should be made non-weight bearing and elevation should be encouraged.

All patients should be referred to and discussed with orthopaedics.

Closed fractures

- Nonoperative management: generally involves a hinged knee brace. Can partial weight bear for 8-12 weeks. Indications for non-operative management include non-ambulant patients or minimally displaced fractures with non-injured ligaments (varus/valgus stability)

- Operative management: open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). Indications for operative management include an articular step (depression in the surface) >3mm, condylar widening >5mm or gross instability.

Open fractures

If an open injury, macroscopic debris should be removed and medical photography arranged, no washout should be completed in AE. Dress with saline-soaked gauze and urgently refer to orthopaedics/plastic surgery. The risk of compartment syndrome should be considered and anticipated.

Initial management is as per BOAST guidelines. The risk of compartment syndrome should be considered and anticipated.

External fixators are often used as a temporising measure in severe open fractures with contamination. Staged procedures to wash, debride and later fix the fracture can be arranged.

Complications

A number of complications may follow a tibial plateau fracture and surgical fixation.

- Early osteoarthritis

- Non-union/ mal-union

- Post-operative infection

Last updated: March 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback