Wrist fractures

Notes

Introduction

Fractures of the distal radius are common orthopaedic injuries.

Wrist fracture is a term that can refer to any fracture affecting the distal radius, ulna or carpal bones. However, generally, it is used interchangeably to describe a fracture of the distal radius and any accompanied ulna fracture. Isolated fractures of carpal bones tend to be considered separately. This note will focus on fractures of the distal radius (e.g. Colles' and Smith's fractures)

Fractures of the distal radius exhibit a bimodal distribution; they are seen in the young following high-energy injuries and as fragility fractures in the elderly. Treatment aims to optimise functional recovery and can be conservative with cast immobilisation or involve surgical fixation.

Anatomy

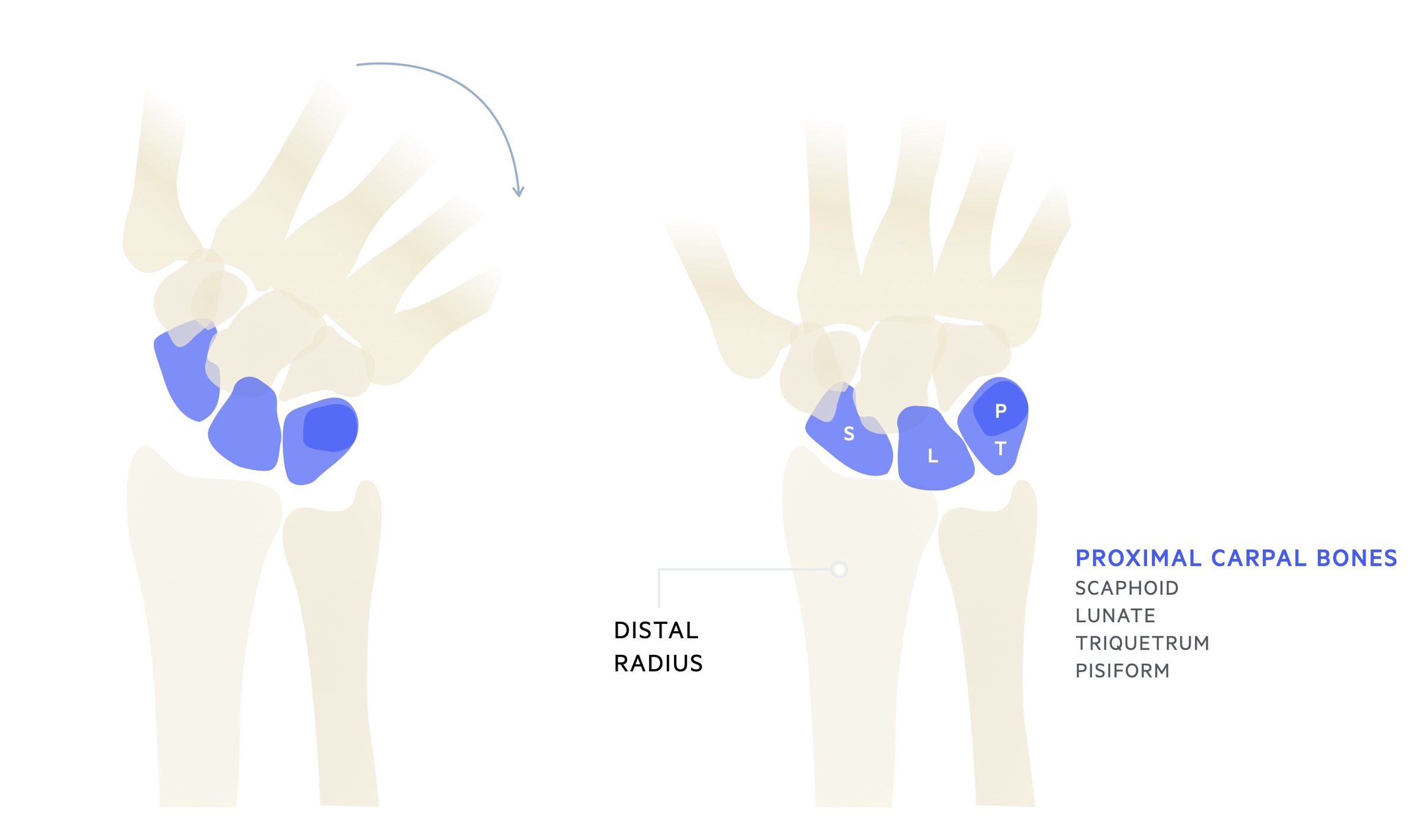

The wrist is a synovial joint formed by the distal radius, articular disc and proximal carpal bones.

The radiocarpal (wrist) joint is a synovial joint formed by the distal articular surface of the radius and the articular disc with the scaphoid, lunate and triquetrum. It is a biaxial and ellipsoid joint. The ulna does not form part of the radiocarpal joint.

Whilst held in a neutral position only the scaphoid and lunate are in contact with the radius and articular disc. When the wrist is held in adduction the triquetrum comes into contact with the articular disc.

Fracture patterns

Fractures may be described based upon region, displacement, comminution and angulation.

Colles' and Smith's are frequently discussed fracture patterns when taught as students. You will find however in practice, at trauma meetings these eponyms are rarely used - instead replaced with a clear verbal description of the radiological appearances of the fracture. It remains important however to be aware of these eponyms and their meanings.

They are described based on the angulation of the distal radial fragment, as such, you must be aware of two terms:

- Dorsal surface: refers to the back or upper side. In the hand, this describes the back of the hand.

- Ventral surface: refers to the front or lower side. In the hand, this describes the palm of the hand.

Colles' and Smith's are both classically considered to be extra-articular fractures (fractures that do not involve the articular surface). Intra-articular fractures of the distal radius are called Barton's fractures (described below).

Colles’ fracture

A type of distal radius fracture defined as an extra-articular fracture of the metaphyseal region of the radius with dorsal angulation (of the distal fragment) and impaction. It is classically caused by a 'fall onto outstretched hand' (or FOOSH - an acronym you will often see in orthopaedic clerkings). There is an associated fracture of the ulna styloid in around 50% of cases.

Smith’s fracture

Often described as a reverse Colles’. Refers to a fracture of the distal radius with volar angulation of the distal fragment. Tend to be inherently less stable than fractures with dorsal angulation.

Smith's fractures tend to result from a fall onto a flexed hand or a direct blow to the back of the wrist.

Barton fracture

Barton fracture describes an intra-articular fracture of the distal radius. Intra-articular involvement increases the risk of arthritis and reduced function. They may have dorsal angulation or volar angulation (volar Barton).

Aetiology

Distal radius fractures most commonly result from a fall onto an outstretched hand (FOOSH).

Fractures of the distal radius may be broadly categorised as high-energy fractures (typically young patients, e.g fall from bike or motorcycle) and fragility fractures (typically elderly, fall from standing height).

Colles’ fracture tend to occur with a fall onto a extended wrist. Smith’s fractures tend to occur with a fall onto a flexed wrist.

Note: In a cohort of patients the fracture will be a symptom of an underlying condition, particularly in the elderly. Always ask yourself why the patient fell! In those whose histories do not support a mechanical fall consider cardiac and neurological causes of falls, loss of consciousness or imbalance.

Clinical features

Fractures of the distal radius are acute injuries, patients will present with pain, swelling and reduced function of the affected joint.

Symptoms

- Pain

- Reduced range of movement

Signs

- Boney tenderness

- Swelling

- Deformity

All patients should have a full assessment (and documentation) of the limbs neurovascular status. Complete a full-body assessment for associated injuries.

Investigations & diagnosis

The diagnosis of a wrist fracture may be made clinically and confirmed by a wrist radiograph.

Bedside

- Observations

- Urine dip

- ECG

Bloods

- FBC

- U&Es

- CRP

- Bone profile

- Vitamin D

- Group & save

- Clotting screen

Imaging

- Wrist X-ray: PA and lateral films.

- CT: allows accurate delineation of the extent of the fracture and any intra-articular involvement (not routinely required).

- MRI: allows assessment of soft tissue injuries (not routinely required).

PA and lateral of a Colles' fracture (note the dorsal angulation of the distal radial fragment)

Additionally, a fracture of the ulnar styloid is seen

Image courtesy of Lucien Monfils

Management

The goal of treatment is to restore normal anatomical alignment to encourage healing and preserve functionality.

Management of distal radius fractures is complicated and depends on a myriad of factors. Surgical fixation is reserved for patients who are likely to have poor functional outcomes from closed reduction and cast immobilisation alone - and in whom surgery would improve outcomes.

These include fractures that are intra-articular (and displaced), significantly comminuted or show significant radial shortening. Fractures that are unstable in cast with progressive dorsal angulation and loss of radial height should also be considered for operative intervention. Operative options include ORIF (normally volar approach with volar plate), external fixation and percutaneous K-wires.

Below represents a general framework (though a simplified one) on the management of these fractures. They are in part based upon BOAST The Management of Distal Radial Fractures 2017 and BSSH Best Practice for Management of Distal Radial Fractures 2018.

Initial management

The majority patients presenting with fractures of the distal radius receive their initial management in ED. For those with extra-articular fractures most will attempt a closed reduction and cast immobilisation with appropriate analgesia (e.g. haematoma block and gas & air).

The aim is to restore normal anatomical alignment of the distal radius. Patients are then referred to orthopaedics (or plastic surgery) for review and decision on definitive management.

Dorsal angulation

Under 65

The fracture, patient wishes and co-morbidities will be considered. Review should include examination of the ulnar variance, dorsal tilt and intra-articular step (if present).

Surgery will typically be considered. If closed reduction is possible then K-wire fixation if generally preferred to ORIF (open reduction and internal fixation).

Over 65

In more elderly patients non-operative management will be likely considered as definitive management. Where there is instability, significant deformity or neurological compromise surgery will be considered.

Volar angulation

Volar angulated fractures are inherently unstable. As a general rule these are managed with open reduction and plate fixation. Once again radiographical findings, patient co-morbidities and wishes must be taken into account.

Note: Open fractures should be managed as per the BOAST open fracture guideline.

Complications

A number of complications may occur as a result of a distal radius fracture or its management.

Early

- Median nerve neuropathy

- Ulnar nerve neuropathy

- Extensor pollicis longus or flexor pollicis longus rupture

- Compartment syndrome

Medium to late

- Osteoarthritis

- Non-union / mal-union

- Complex regional pain syndrome

- Metalwork infection

- Metalwork irritation

Last updated: October 2021

Further reading

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback