Carpal tunnel syndrome

Notes

Overview

Carpal tunnel syndrome is a median nerve neuropathy due to compression as it passes through the carpal tunnel in the wrist.

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is due to compression of the median nerve as it passes through the carpal tunnel in the wrist leading to median nerve neuropathy. It is considered the most common upper limb mononeuropathy.

CTS is common and usually presents with paraesthesia and/or sensory loss of the first three fingers (thumb, index finger, middle finger), lateral half of the fourth finger (ring finger). As the condition progresses, there is loss of motor function with hand weakness, wasting of the thenar eminence, and weakness in thumb abduction. Symptoms are characteristically worse at night and may disrupt sleep.

Treatment can be with non-surgical measures (e.g. steroid injections, wrist splints) or surgical measures (e.g. carpal tunnel decompression) depending on the severity.

Epidemiology

CTS is common and may be bilateral.

CTS is common in adults with a prevalence as high as 5% in the general population. There is an estimated 3:1 female-to-male ratio. Bilateral involvement is commonly observed.

Aetiology & pathophysiology

CTS is due to compression of the median nerve as it passes through the carpal tunnel in the wrist.

As the median nerve crosses the wrist, it passes through the carpal tunnel. Compression here is typically due to anatomic compression and inflammation. Several risk factors have been identified that increase the risk of median nerve compression in this region.

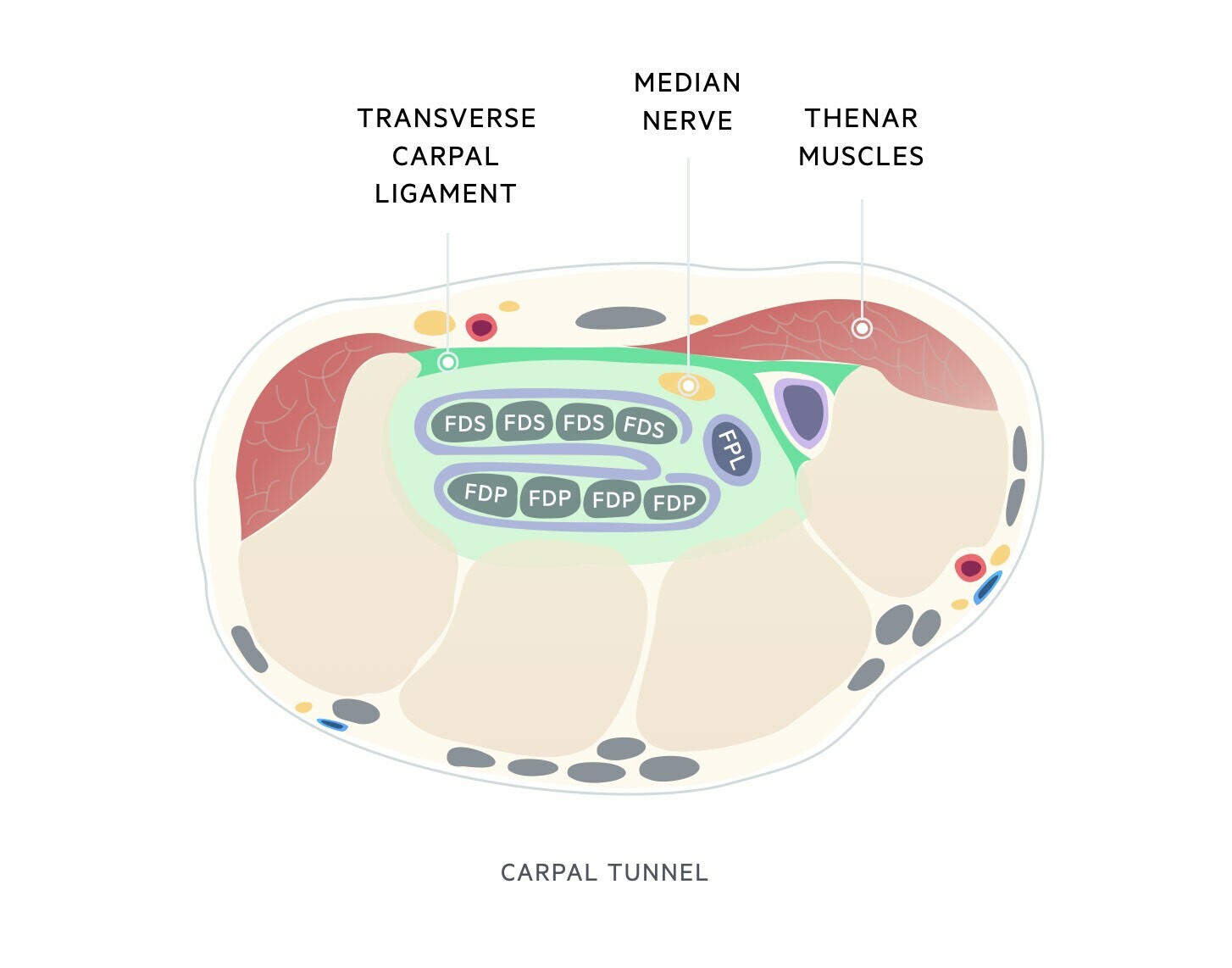

Carpal tunnel

The carpal tunnel has two key boundaries superiorly and inferiorly:

- Superior boundary: Flexor retinaculum, also known as the transverse carpal ligament. On the ulnar side of the wrist, it is attached between the pisiform bone and hook of the hamate bone. On the radial side of the wrist, it attaches to the scaphoid bone and part of the trapezium bone

- Inferior boundary: carpal bones of the wrist (hamate, capitate, trapezoid and trapezium)

Through the carpal tunnel runs the median nerve and nine flexor tendons.

Median nerve

The median nerve is derived from the lateral and medial cords of the brachial plexus (C5-T1). It enters the upper arm at the axilla and travels alongside the brachial artery into the cubital fossa. It then travels in the anterior forearm before passing through the carpal tunnel to supply some intrinsic muscles of the hand.

Sensory function

The median nerve provides sensory innervation to the hand. This includes the palmar and distal dorsal aspects of the lateral three-and-a-half digits (thumb, index, middle, and half of the ring finger) and central palm. The sensation of the palm is provided by the median nerve and a small sensory branch known as the palmar cutaneous, which branches before the carpal tunnel.

Motor function

In the forearm, the median nerve provides innervation for:

- Pronator teres

- Flexor carpi radialis

- Palmaris longus

- Flexor digitorum superficialis

A branch of the median nerve known as the anterior interosseous arises within the forearm and provides innervation for:

- Pronator quadratus

- Flexor pollicis longus

- Part of the flexor digitorum profundus

Within the hand, the median nerve provides motor innervation to the thenar eminence muscles and two lateral lumbricals that can be remembered as ‘2LOAF’. This is why prolonged compression can lead to thenar eminence wasting

Risk factors

There are a number of risk factors associated with the development of CTS. These include:

- Gender (female sex increases risk)

- Diabetes mellitus

- Osteoarthritis

- Obesity

- Hypothyroidism

- Pregnancy

- Trauma

There is also limited data on the role of genetic factors and environmental factors such as repetitive hand and wrist use or work with vibrating tools.

Pathophysiology

The precise cause of increased pressure within the carpal tunnel is unknown. However, evidence suggests it may be related to anatomic compression (e.g. fibrosis of the flexor tendons, mass lesion, or an anatomically small tunnel) and inflammation of the nerve itself in response to the compressive injury.

Clinical features

CTS is characterised by pain and/or paraesthesia in the distribution of the median nerve.

Early symptoms of CTS are those of pain and/or paraesthesia. As the disease progresses, overt sensory loss can develop in the distribution of the median nerve in association with hand weakness and thenar eminence muscle wasting.

Symptoms

Sensory symptoms are usually limited to the median-innervated fingers (thumb, index, middle, and lateral half of ring finger). Symptoms may be unilateral or bilateral.

- Pain: often felt as a dull ache or discomfort. It may be felt in the wrist, fingers, or sometimes forearm

- Paraesthesia

- Weakness

- Clumsiness

- Difficulty with tasks (e.g. opening jars, buttoning shirts)

- Sensory loss

Initial symptoms are often noted at night and may wake patients from sleep. CTS may progress becoming noticeable during the day as well. Symptoms are usually exacerbated by activities that promote extended periods of wrist extension or flexion (e.g. driving).

Signs

Overt sensory loss and muscle weakness are usually late signs.

- Sensory loss: over median-innervated fingers. Thenar eminence is spared as the palmar cutaneous branch that supplies this area arises proximal to the wrist.

- Thenar eminence wasting

- Weak thumb abduction

- Weak thumb opposition

Provocation manoeuvres

Pressure within the carpal tunnel increases if the hand is extended or fully flexed, which can exacerbate symptoms. The tunnel is under the least amount of pressure when the hand is hand is in a neutral (i.e. flat) or slightly flexed position.

Several bedside tests can be performed in an attempt to provoke symptoms of CTS and improve the likelihood of making a clinical diagnosis. The two main tests are Phalen and Tinel.

- Phalen manoeuvre: ask the patient to hyperflex both hands and hold dorsal surfaces together. This should be held for 1 minute. A positive test leads to pain and/or paraesthesia in the distribution of the median nerve

- Tinel test: percuss over the median nerve just proximal to the carpal tunnel. A positive test leads to pain and/or paraesthesia in the distribution of the median nerve

Diagnosis & investigations

The diagnosis of CTS is usually made clinically but can be confirmed on electrodiagnostic tests.

CTS is usually a clinical diagnosis based on characteristic signs and symptoms. Clinical features can be used to determine the severity of CTS.

- Mild: symptoms in the distribution of the median nerve (e.g. numbness, tingling, discomfort), but no sensory loss, no motor weakness, and no effect on hand function and activities of daily living

- Moderate: sensory loss in the distribution of the median nerve. Deterioration in hand function but able to perform all activities of daily living. May disrupt sleep quality

- Severe: weakness in the distribution of a median nerve OR symptoms disrupt activities of daily living OR routinely disputs sleep

Electrodiagnostic testing

Electrodiagnostic tests include both nerve conduction studies and electromyography:

- Electromyography (evaluates muscle units): this refers to an assessment of the electrical activity of muscles. It can assess activity during rest and voluntary contraction. Records the electrical potentials generated in a muscle belly through the insertion of a needle

- Nerve conduction studies (evaluates peripheral nerves): this refers to an assessment of individual peripheral nerve function. It essentially involves activating nerves electrically over several points on the skin of the upper/lower limbs and measuring the response. The test involves assessing both the size (i.e. amplitude) and speed (i.e. velocity) of signals through motor and sensory fibres

Electrodiagnostic tests are usually reserved for the following groups:

- Atypical presentations

- Moderate-to-severe symptoms

- Progression despite non-surgical treatment

If nerve conduction studies are completed it will show impaired conduction across the carpal tunnel. These can be combined with electromyography, especially if there is concern about another pathology (e.g. plexopathy, radiculopathy) or surgical management is being considered because EMG can grade the severity.

Imaging

Imaging (e.g. US or MRI) is usually reserved for patients with a suspected structural abnormality such as a cyst or tumour.

Management

Treatment of CTS can be non-surgical or surgical.

The choice between non-surgical or surgical options in CTS depends on the severity and response to any previous treatments.

Non-surgical

Non-surgical options include wrist splints, physical therapy, and/or corticosteroids. These options are generally indicated for patients with mild-to-moderate CTS. Wrist splints help to hold the wrist in a neutral position and thus reduce the pressure within the carpal tunnel. They are often worn at night but can be worn continuously throughout the day.

Corticosteroids can be injected into the region of the carpal tunnel for short-term relief of symptoms. They are generally given at most once every six months and if symptoms recur after two injections other options should be considered (e.g. surgery).

Surgical

Surgical decompression is highly effective for CTS and should be offered to patients with evidence of severe median nerve injury or those who have failed to respond to non-surgical measures. Surgery should generally not be offered during pregnancy because symptoms usually improve a few weeks after delivery.

A variety of different surgical techniques can be used to release pressure within the carpal tunnel. These include:

- Open carpal tunnel release

- Endoscopic carpal tunnel release

- US-guided minimally-invasive release

The most frequent complication of CTS surgery is incomplete release and this may lead to reoperation. Other complications include:

- Wound infection

- Scar formation

- Vascular injury

- Nerve injury

- Complex regional pain syndrome

Last updated: August 2022

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback