Testicular cancer

Notes

Overview

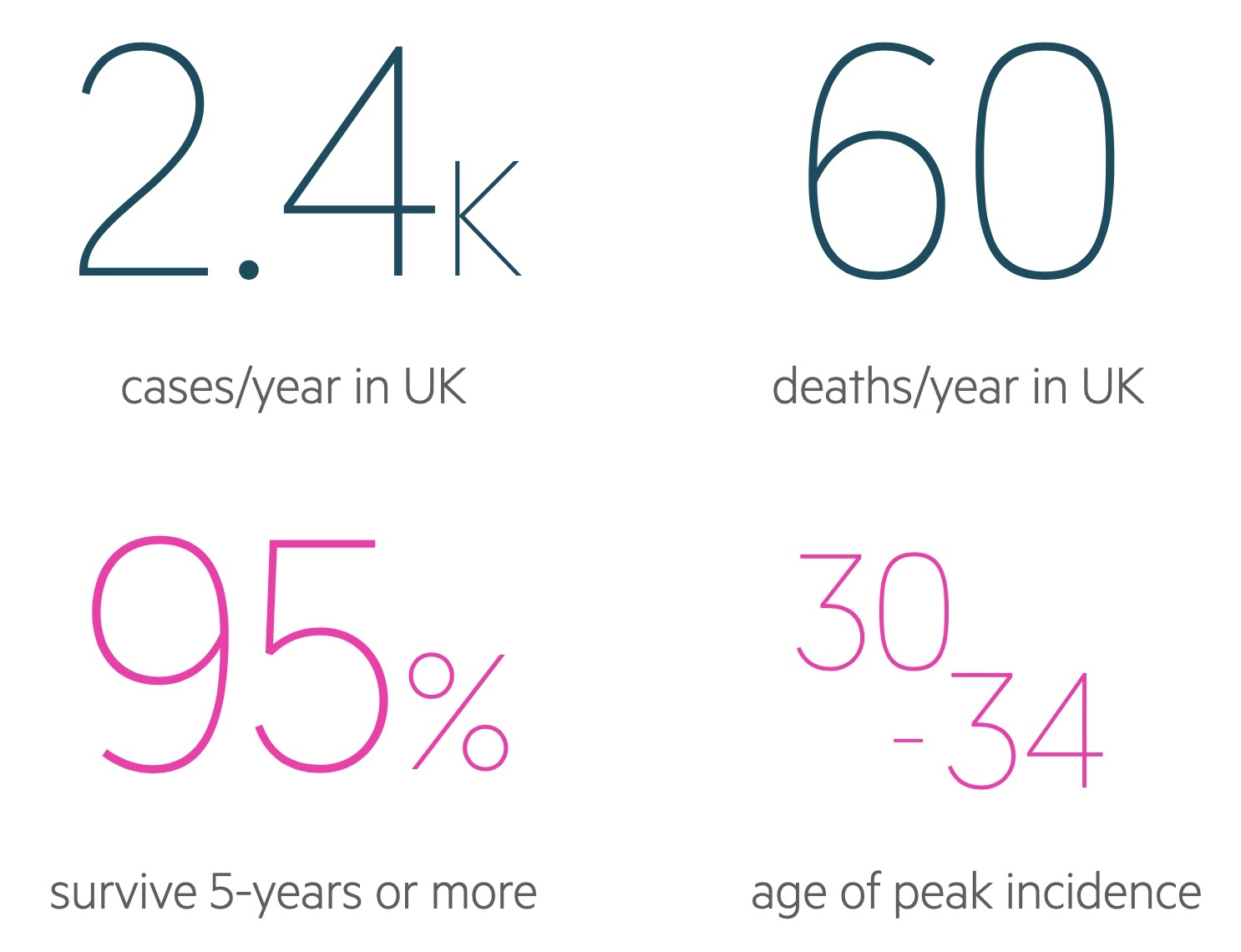

Testicular cancer is responsible for 1% of all new cancers in men.

It typically presents with a unilateral testicular mass. Incidence appears to be increasing, with approximately 3-10 cases / 100,000 men each year in the Western world.

The vast majority of testicular cancers are germ-cell tumours (95%). Overall prognosis, following appropriate therapy, is good.

As with all cancers, optimal management requires a multi-disciplinary approach with GPs, specialist nurses, urologists and oncologists all essential.

Figures from Cancer Research UK (last accessed Nov 2021).

Epidemiology

There are approximately 2,300 cases of testicular cancer in the UK each year.

It is the 18th most common cancer affecting men in the UK, accounting for around 1% of cancer cases in men each year. Incidence has increased by 24% from the mid 1990's to the mid 2010's.

Incidence rises in adolescence, peaks between the ages of 30-34, before falling significantly over the subsequent decades. There is a small rise in incidence over the age of 90.

Risk factors

There are a number of risk factors associated with testicular cancer.

- Cryptorchidism

- Hypospadias

- Infertility

- Klinefelter’s syndrome

- Tall men

Classification

Testicular germ cell tumours can be classified as seminoma and non-seminomatous germ cell tumours.

The vast majority of testicular tumours are germ cell in origin (95%). The two major types are seminoma and non-seminomatous germ cell tumours. Other tumour types are also seen, but these are far less common.

Germ cell tumours

- Seminoma

- Non-seminomatous germ cell tumours (NSGCT):

- Embryonal carcinoma

- Yolk sac tumour

- Choriocarcinoma

- Teratoma

- Mixed

Sex cord/gonadal stromal tumours

- Leydig cell tumour

- Sertoli cell tumour

- Granulosa cell tumour

- Thecoma/fibroma group of tumours

Presentation

Testicular cancer most commonly presents with a unilateral scrotal mass.

Clinical features are typically scrotal, but systemic features may be seen:

- Testicular lump

- Testicular pain/discomfort

- Back pain, flank pain (indicative of metastasis)

- Lymphadenopathy

- Gynaecomastia (more common in NSGCT)

Referral

Cases of suspected testicular cancer should be referred urgently via a two-week wait pathway.

NICE NG 12 recommends referring all men with non-painful testicular enlargement or change in size or change in texture via a two-week wait pathway to urology. Additionally refer patients describing a dragging sensation, new varicocele or hydrocele.

Suspect testicular cancer in patients with unexplained retroperitoneal masses or suspected metastasis on imaging. Also suspect in men presenting with infertility or with elevated AFP / hCG.

Refer any patient with suspected testicular cancer to urology via a two-week wait.

Diagnosis

Testicular USS is the diagnostic modality of choice.

After referral, the patient will be seen by Urology who will take a history and examine the patient. Examination should involve assessment of lymphatic chains. An urgent testicular USS is needed.

USS offers excellent visualisation and identifies likely malignant lesions (the diagnosis is confirmed with histology following an orchidectomy). Its sensitivity approaches 100% in trained hands.

Both testes must be examined. Bilateral disease complicates around 1% of cases.

Pre-op care

A number of investigations must be arranged prior to orchidectomy.

Bloods

- FBC

- Renal function

- LFT

Imaging

CXR: may identify pulmonary metastasis.

Tumour markers

Tumour markers may be measured to support the diagnosis and offer prognostic information. However, normal levels do not exclude cancer and levels may be elevated in other pathologies. The three major markers are:

- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP): may be seen in NSGCT, particularly the yolk sac subtype. AFP is not seen in pure seminoma.

- Beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin (beta-hCG): may be seen in NSGCT, particularly the choriocarcinoma subtype. Can also be seen in seminomas.

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH): general marker of increased cell turnover, may be raised in either seminomas or NSGCTs.

As a general rule, these markers are more likely to be elevated in advanced disease. Whilst they are commonly absent, when they are present they are particularly useful for post-operative monitoring for tumour recurrence.

Placental alkaline phosphatase may also be measured and is indicative of seminoma.

Fertility

Fertility should be discussed with patients prior orchidectomy.

Sperm cryopreservation should discussed with patients who have not completed their families, particularly if there is an abnormality in the contralateral testicle.

Oncology referral

Oncology referral may take place prior to or immediately after surgery. If there is evidence of metastatic disease on initial investigations further staging scans may be arranged pre-operatively.

Those with widespread disease should be discussed with and reviewed by oncology prior to surgery.

Orchidectomy

Orchidectomy should be performed in virtually all cases.

It is both diagnostic - enabling tissue diagnosis - and therapeutic in removing the tumour.

Orchidectomy must be performed via an inguinal approach. This is to avoid crossing lymph networks - the testicles lymph drain to para-aortic nodes whilst the scrotal skin drains to the inguinal nodes.

The contralateral testicle may be biopsied if carcinoma in situ is suspected.

Post-op investigations

Following orchidectomy, a tissue diagnosis and staging investigations should be obtained.

Histology

Histology should be processed urgently to obtain a tissue diagnosis.

Tumour markers

Tumour markers should be repeated post-operatively. In patients in whom levels were elevated pre-op, they should be repeated weekly until they normalise.

- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)

- Human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG)

- LDH

Imaging

- CT chest, abdomen and pelvis: allows disease staging.

- Bone scan: may be considered if symptoms suggest involvement

- CT/MRI head: may be considered if symptoms suggest involvement, multiple lung metastasis or very elevated beta-hCG

Staging

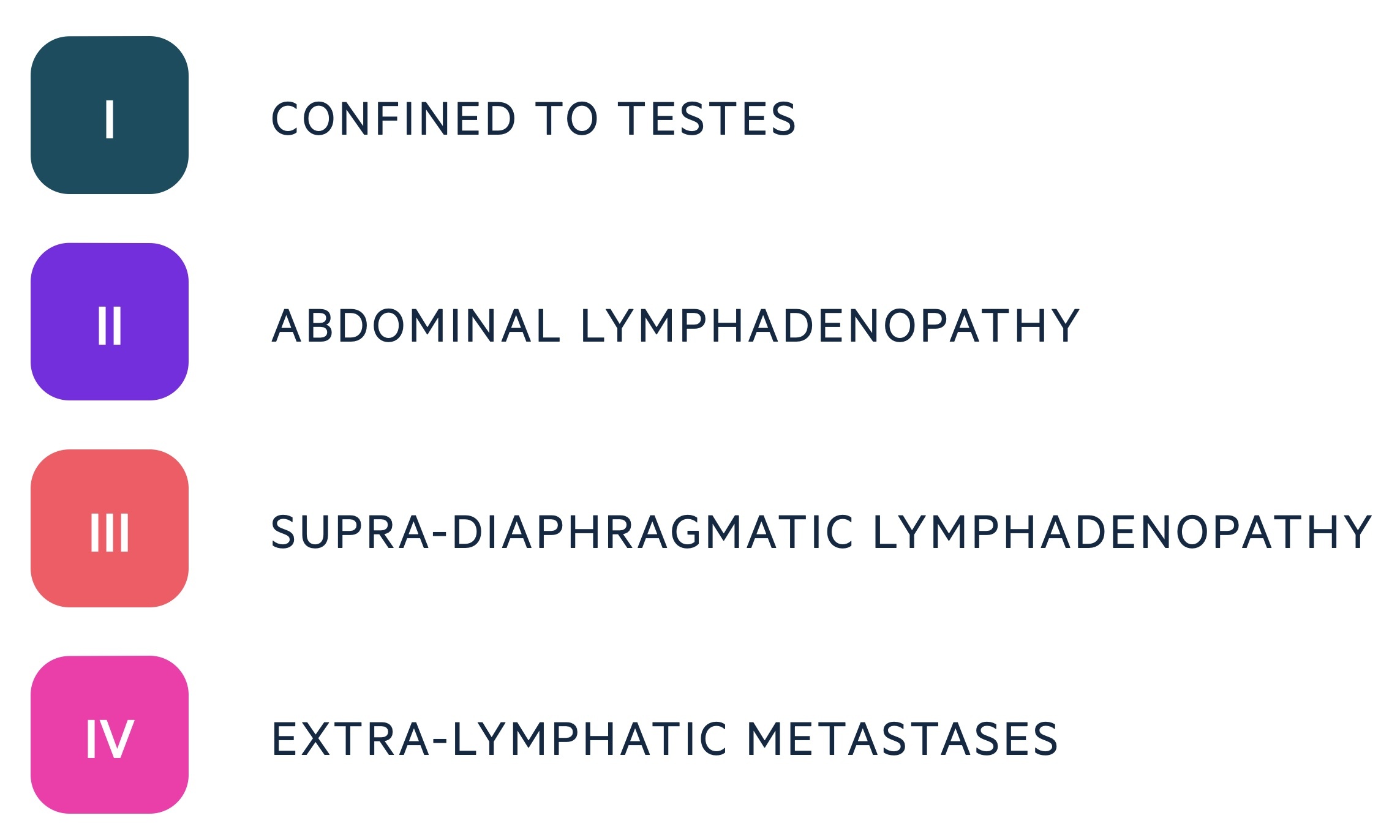

Testicular cancer may be staged using a number of systems.

Two commonly used staging systems are the Royal Marsden Hospital (RMH) Staging Classification and the International Germ Cell Consensus Classification system (IGCCC). The SIGN guidelines advise the use of IGCCC. The intricacies of each system would not typically be expected at an undergraduate level. Instead a general understanding of the underlying principles are needed.

RMH staging

Historically this was the most commonly used staging system. A simplified version of the RMH staging is shown.

IGCCC

IGCCC uses prognostic grouping, dividing patients into good prognosis, intermediate prognosis and poor prognosis. Grouping involves primary site, metastasis and tumour markers.

Oncological management

Oncological management is complex and may involve surveillance, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

The intricacies of oncological management are beyond the scope of this note. For those interested see the further reading section below to gain a greater understanding.

Here we will discuss some of the general principles of management

Stage 1 disease

Stage 1 disease is described as no residual disease following orchidectomy.

- Seminoma: may be managed with surveillance, adjuvant carboplatin or radiotherapy.

- NSGCT / mixed seminoma: may be managed with surveillance or adjuvant bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy.

Metastatic disease

Management is highly dependent on exact staging.

- Seminoma: management may involve chemotherapy (e.g. cisplatin), radiotherapy or both.

- NSGCT: management typically consists of adjuvant bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy.

Prognosis

The overall prognosis is good, though is dependent on tissue type and disease extent.

Figures from Cancer Research UK (last accessed Nov 2021) show overall figures off:

- 1-year survival: 96.5%

- 5-year survival: 95.3%

Survival is significantly better for younger men. Almost all men aged 15-49 will survive 5-years or more whilst only two-thirds older than 80 do.

Last updated: March 2021

Further reading:

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback