Oxygen

Notes

Overview

Oxygen should be regarded as a drug that is prescribed for patients with hypoxaemia (low blood oxygen concentration).

Oxygen is the most commonly used drug in emergency situations. It can be a life-saving drug to prevent severe hypoxaemia that refers to a low arterial oxygen concentration. However, used inappropriately oxygen can have serious or fatal consequences.

The headline point is that oxygen should be used to treat hypoxaemia and maintain a patients’ saturations in the target range. This should be 94-98% or 88-92% in patients at risk of type 2 respiratory failure.

When prescribing and administering oxygen there are several things to consider:

- Does the patient need oxygen?

- What are the target saturations?

- How should oxygen be delivered?

- What is the cause of hypoxaemia?

- What is the ongoing monitoring?

In this note we discuss the principles of oxygen prescribing. For more detailed information, see the British Thoracic Society guideline on oxygen use in healthcare and emergency settings.

Hypoxia & hypoxaemia

Hypoxia and hypoxaemia are two different terms but often used synonymously in clinical practice.

In clinical practice, the term ‘hypoxic’ is commonly used instead of ‘hypoxaemic’ to refer to a patient with low oxygen saturations as measured on pulse oximetry. Although the terms hypoxia and hypoxaemia are used interchangeably, they mean two different things:

- Hypoxia: failure of tissue oxygenation

- Hypoxaemia: low arterial oxygen concentration (i.e. low partial pressure of blood oxygen)

Arterial oxygen concentration is measured in kPa. The normal partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood is 10.6–13.3 kPa. Low arterial oxygenation is known as hypoxaemia and this is the most common cause of hypoxia. However, hypoxia may occur in the absence of hypoxaemia if the peripheral tissue cannot utilise oxygen or oxygen delivery is impaired (e.g. anaemia).

The five causes of tissue hypoxia include:

- Hypoxaemic hypoxia: due to hypoventilation, ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) mismatch, or pulmonary shunts

- Circulatory hypoxia: due to inadequate cardiac output

- Anaemic hypoxia

- Histotoxic hypoxia: inability of the tissue to use oxygen (e.g. cyanide poisoning)

- Oxygen affinity hypoxia: decreased oxygen delivery to tissue (i.e. haemoglobin holds onto oxygen)

For more information, see our notes on Respiratory failure.

Indications for oxygen

The sole indication for oxygen is hypoxaemia.

Patients with hypoxaemia require oxygen to prevent hypoxia. This is because hypoxia impairs cellular aerobic metabolism. When aerobic metabolism is impaired cells undergo anaerobic respiration, but this is a short-term inefficient system that cannot sustain life for prolonged periods of time. By-products of anaerobic respiration include substances such as lactic acid that can lead to metabolic acidosis and reduced cellular function.

Oxygen is prescribed for two main groups with hypoxaemia:

- Acutely unwell: typically administered in a hospital or healthcare setting.

- Chronic hypoxaemia: oxygen may be prescribed for long-term use in patients with chronic lung disease. This is known as long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT). Specific criteria exist for its use.

Acute indication

Hypoxaemia is a common presentation in critically ill patients. Often, patients may be so unwell that oxygen is administered at high flow rates while waiting for a reliable oximetry reading. Once obtained, oxygen can be titrated to the appropriate target saturations.

Oxygen should always be administered to achieve a normal or near-normal oxygen saturation based on the target saturation set for the patient (see below).

Target saturations

Patients with, or at risk of, type 2 respiratory failure should have a lower target saturation at 88-92%.

There are two major target saturations for patients being treated with oxygen:

- 94-98%: patients not at risk of type 2 respiratory failure

- 88-92%: patients with, or at risk of, type 2 respiratory failure

The target saturations should be clearly documented or recorded in the patient records.

Type 2 respiratory failure

Type 2 respiratory failure (T2RF) is characterised by hypoxaemia (PaO2 < 8 kPa) and hypercapnia (PaCO2 > 6.5 kPa). It is also referred to as hypercapnic respiratory failure. It can be either acute or chronic depending on its speed of onset and presence of compensatory mechanisms.

Patients at risk of T2RF include:

- Moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): may be undiagnosed

- Cystic fibrosis

- Severe obesity (i.e. obesity hypoventilation syndrome)

- Neuromuscular disease (e.g. Motor neurone disease)

- Severe chest wall deformity (e.g. kyphoscoliosis)

- Previous episode of T2RF

In patients with, or at risk of, T2RF higher levels of oxygen can induce or worsen hypercapnia due to a combination of ventilation/perfusion mismatch and increased physiological deadspace. Therefore, we can get oxygen-induced hypercapnia.

Undiagnosed patients

In a patient without a known diagnosis that increases the risk of T2RF such as COPD, it may be difficult to determine whether they should have a lower target saturation at 88-92%.

Features that can suggest a patient is at risk of T2RF:

- Heavy smoker

- Severe emphysematous changes on imaging

- Compensated respiratory acidosis (i.e. raised PaCO2 & raised bicarbonate)

- History of obstructive sleep apnoea

- Large neck or very obese

- Rising PaCO2 with oxygen therapy

If in doubt, always ask a senior for advice on target saturations.

Delivery devices

The amount of oxygen that is delivered to a patient to maintain their saturations depends on the device used.

Different devices can be used to deliver oxygen to a patient to maintain oxygen saturations within their target range. These devices vary on the mechanism of delivery, concentration of oxygen given, and whether the delivery of oxygen is fixed or variable.

Nasal cannulae

- Oxygen delivered (%): 24-44%

- Variable oxygen concentration: affected by respiratory rate and amount delivered via nose.

- Flow rate (L/min): 1-6 litres

In general, more than 4 litres is uncomfortable for patients and causes dryness of the nasal passages.

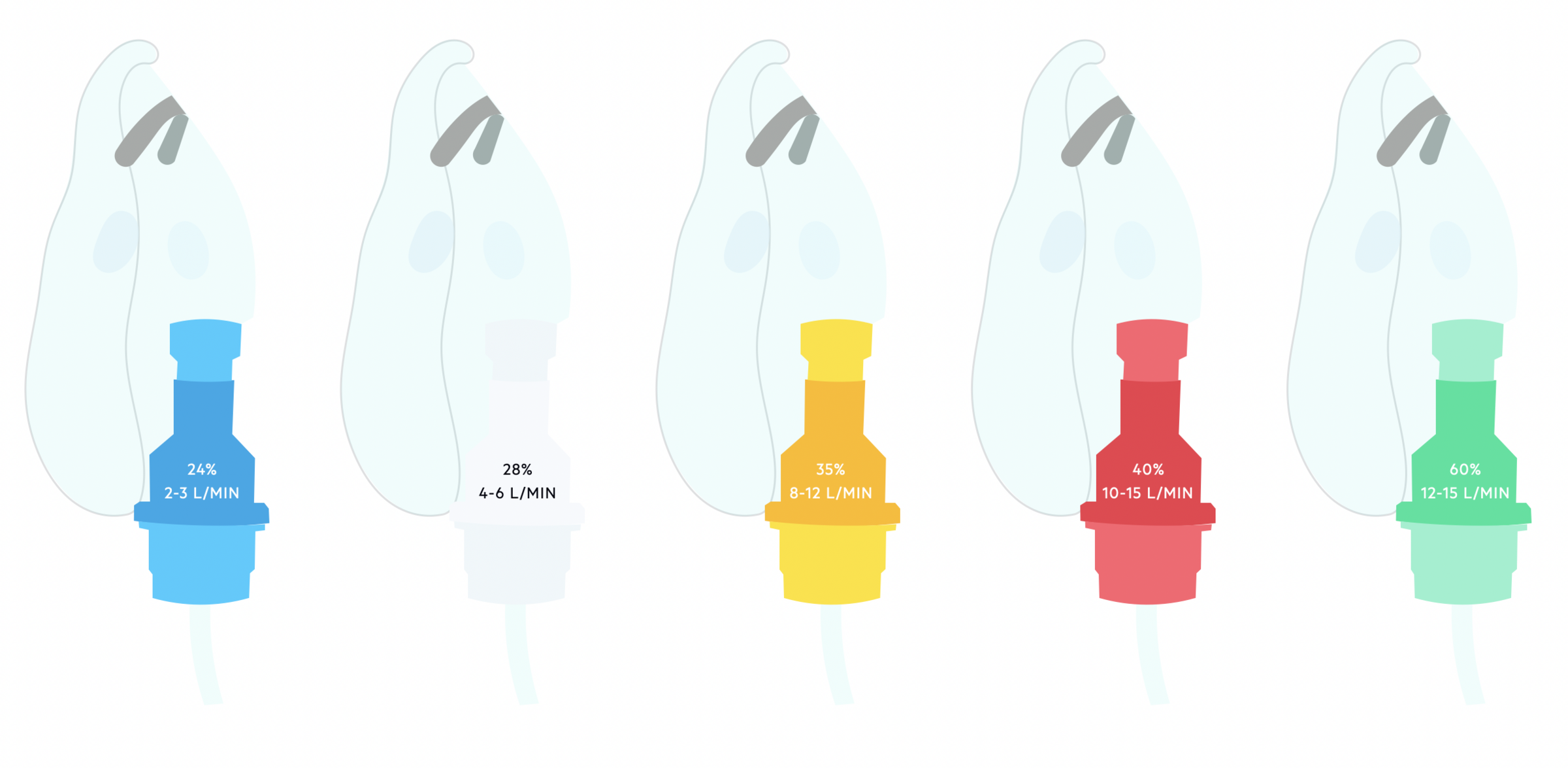

Venturi mask

- Oxygen delivered (%): 24-60%

- Fixed oxygen concentration: designed to entrain a set amount of oxygen and air giving a fixed concentration

- Flow rate (L/min): coloured coded (2-3 Blue / 4-6 White / 8-12 Yellow / 10-15 Red / 12-15 Green)

Simple face mask

- Oxygen delivered (%): 30-60%

- Variable oxygen concentration: affected by respiratory rate

- Flow rate (L/min): 6-10 litres

Non-rebreathe mask

A reservoir bag is connected to the mask with a one-way flap valve.

- Oxygen delivered (%): ~60-85%

- Variable oxygen delivery: affected by respiratory rate

- Flow rate (L/min): 10-15 litres (if lower rates used the reservoir bag can deflate during inspiration)

Humidifed oxygen

May be required for flow rates > 4 L/min due to upper airway dryness and discomfort. A humidifier attachment can be added to some devices

Oxygen titration

If a patient is becoming more hypoxaemic, oxygen should be titrated according to target saturations. Ensure ongoing monitoring using appropriate early warning scores (i.e. NEWS). Patients should undergo blood gas analysis within 1 hour of requiring increased oxygen.

Titration of oxygen

- Stage one - Blue 24% Venturi (2-3 L/min) / Nasal cannulae 1 L/min

- Stage two - White 28% Venturi (4-6 L/min) / Nasal cannulae 2 L/min

- Stage three - Yellow 35% Venturi (8-12 L/min) / Nasal cannulae 4 L/min

- Stage four - Red 40% Venturi (10-15 L/min) / Nasal cannulae 5-6 L/min / Simple face mask 5-6 L/min

- Stage five - Green 60% Venturi (12-15 L/min) / Simple face mask 7-10 L/min

- Stage six - Non-rebreathe with reservoir mask 60-85% (15 L/min)

When monitoring patients on oxygen ensure you look for signs of respiratory deterioration, particularly if you are required to titrate oxygen upwards. These may include:

- Tachypnoea (esp. >30 bpm)

- Desaturation

- Increasing oxygen requirement

- High NEWS score

Respiratory support

Non-invasive and invasive ventilation are a form of respiratory support to aid ventilation.

Patients with severe hypoxaemia may require respiratory support to aid ventilation. In brief, respiratory support is a method of providing pressure-based ventilation to support a patients breathing and improve recruitment of alveoli. There are two major types of respiratory support:

- Non-invasive: does not require tracheal intubation

- Invasive: requires tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation

Non-invasive ventilation

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) is a way of supporting ventilation without having to undergo invasive tracheal intubation. NIV is indicated if high inspired oxygen concentrations (>60%) are not sufficient to maintain adequate oxygenation in patients with respiratory failure.

There are several methods of delivering NIV:

- High-flow nasal cannula oxygen (HFNC): often referred to as ‘Optiflow’. Provides a high concentration of oxygen (up to 80%) and high flow rate (up to 70 L/min). Provides a small amount of positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP - 2-5 cmH20). This essentially helps to recruit alveoli and prevent collapse.

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP): similar to HFNC, CPAP provides a high concentration of oxygen (up to 80%) and high flow rate (up to 70 L/min). It provides a higher amount of PEEP (up to 10 cmH20), which prevents airway collapse, improves alveoli recruitment and improves ventilation/perfusion matching.

- Bi-level Positive Airway Pressure (BiPAP): this provides air pressure during both inspiration and expiration. The expiratory positive airway pressure (ePAP) is similar to PEEP and helps to prevent alveoli collapse and recruit more alveoli for gas exchange. The inspiratory positive airway pressure (iPAP) assists inspiration and is important for ventilation (exchange of gas). The pressure difference between ePAP and iPAP helps increase tidal volume and minute ventilation. BiPAP is usually reserved for patients with, or at risk of, type 2 respiratory failure.

Invasive ventilation

Invasive ventilation is also known as mechanical ventilation. It involves general anaesthesia, invasive tracheal intubation with placement of a tracheal breathing tube, and connection to a mechanical ventilator that does the breathing for the patient.

ECMO

In very severe cases, patients may require Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), which is essentially an artificial lung. This is a very specialised treatment that involves diverting a patients blood to an artificial oxygenator before being pumped back to the patients body. It is used when mechanical ventilation is not sufficient to maintain adequate oxygenation and there is deemed a reasonable chance of recovery.

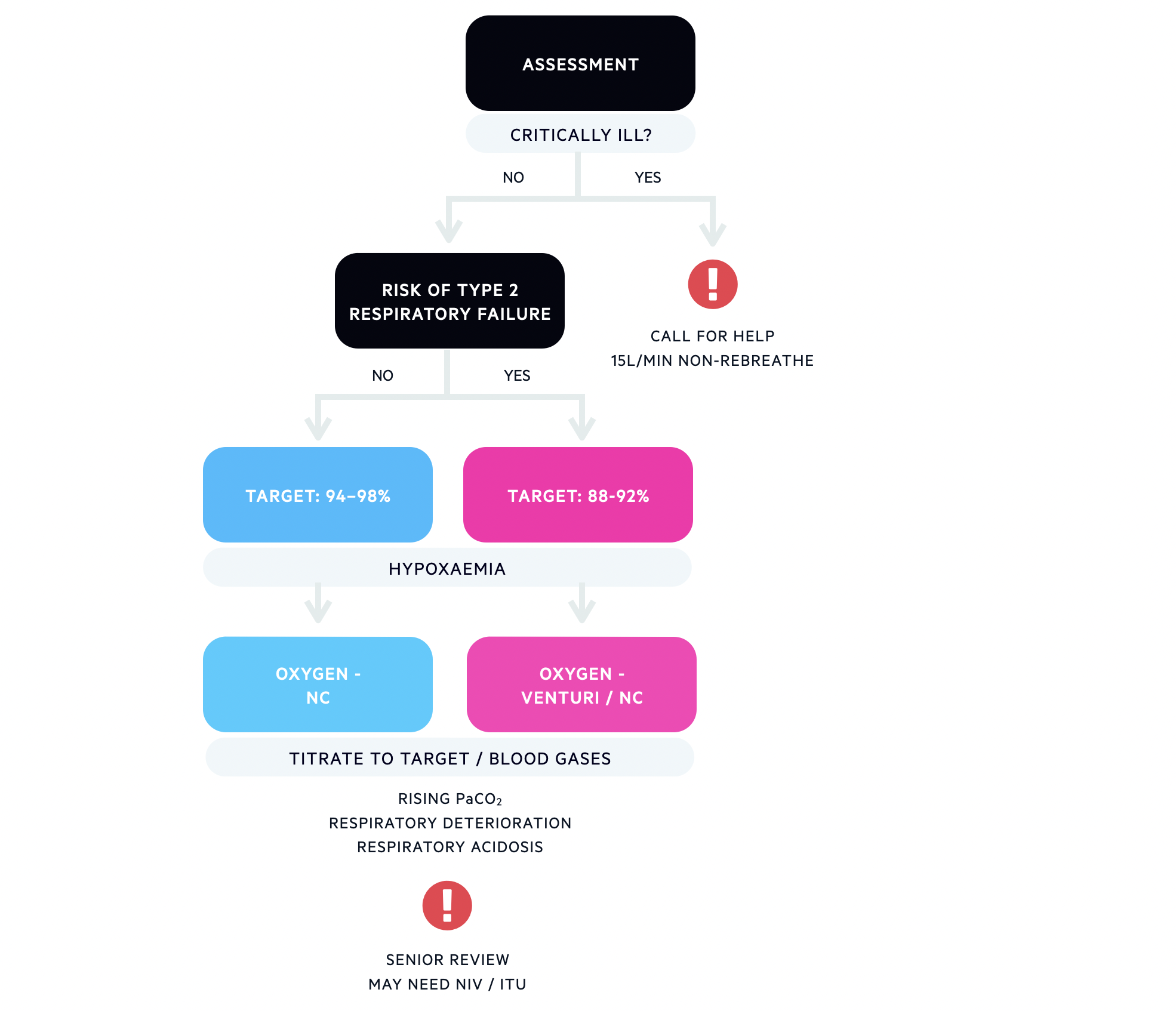

Oxygen prescribing summary

The diagram below shows a summary of oxygen prescribing for acutely hypoxaemic patients in hospital.

Approach to oxygen prescribing in an acutely hypoxaemic patient

NC - nasal cannulae / NIV - non-invasive ventilation / ITU - intensive treatment unit

Last updated: May 2022

References

O'Driscoll, et al. British Thoracic Society Guideline for oxygen use in adults in healthcare and emergency settings. 2017

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback