Gastric cancer

Notes

Overview

Gastric (stomach) cancer is the 17th most common malignancy in adults in the UK.

The stomach is a muscular organ that is part of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. It is located at the distal end of the oesophagus beyond the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ). The stomach is essential for digestion.

The stomach is divided into five anatomical components known at the cardia, fundus, body, antrum and pylorus. The pylorus marks the entry into the duodenum and the whole stomach is composed of columnar epithelium. For more information see our notes on gastrointestinal physiology.

Over 90% of gastric cancers are adenocarcinoma, which is historically divided into two histological subtypes known as intestinal and diffuse (based on Lauren criteria):

- Intestinal-type: most common, gland-forming. Further divided into papillary, tubular or mucinous adenocarcinomas.

- Diffuse-type: less common, composed of discohesive cells. Classically signet cells see on histology. Can lead to extensive infiltration of the stomach and more likely to have a familial element.

The truth is the classification of gastric cancer is more complex and has advanced over time, this is discussed in more detail below.

Epidemiology

The incidence of gastric cancer is highly variable depending on the geographical location.

Across the world, gastric cancer is the fourth most common malignancy. The highest incidence of gastric cancer is found in Eastern Asia (e.g. Korea, Japan), Eastern Europe, and Central and Latin America. The lowest incidence is found in North America, Europe and Africa. In fact, due to the high incidence Japan has a gastric cancer screening programme.

Gastric cancer is more common in older people with >50% of patients in the UK being over 75 years old. It is more common in men and strongly linked to environmental factors (discussed in aetiology).

In the UK, the overall incidence of gastric cancer has been declining, although there has been an increase in adenocarcinomas affecting the gastric cardia, which lies just below the GOJ.

Classification

Gastric cancer may be classified based on anatomy, histology, disease extent or molecular markers.

These classifications broadly apply to gastric adenocarcinomas, which are the most prevalent gastric cancer seen in >90% of cases.

Anatomical

This is the universally accepted classification of gastric cancer, which is based on the tumour, node, metastasis (TNM) classification used for all cancers.

Gastric cancers can be staged according to the size of the tumour, number of nodes involved and presence of distant metastasis. In 2017, further clarification was made on how best to classify cancers affecting the GOJ.

If an upper GI cancer involves the GOJ, it may be classified and treated as an oesophageal or gastric cancer:

- Epicentre of the tumour ≤2 cm from the GOJ: oesophageal cancer

- Epicentre of the tumour >2cm from the GOJ: gastric cancer

Histological

Traditionally, gastric cancer was classified based on the Lauren criteria (1965) into two histological subtypes:

- Intestinal: more commonly seen in males, older ages and better prognosis

- Diffuse: equal sex prevalence, seen in younger patients, worse prognosis.

These subtypes have very different clinical, pathological and molecular features. If diffuse gastric cancer involves a major portion, or all of the stomach, it may be referred to as linitis plastica or ‘leather bottle stomach’.

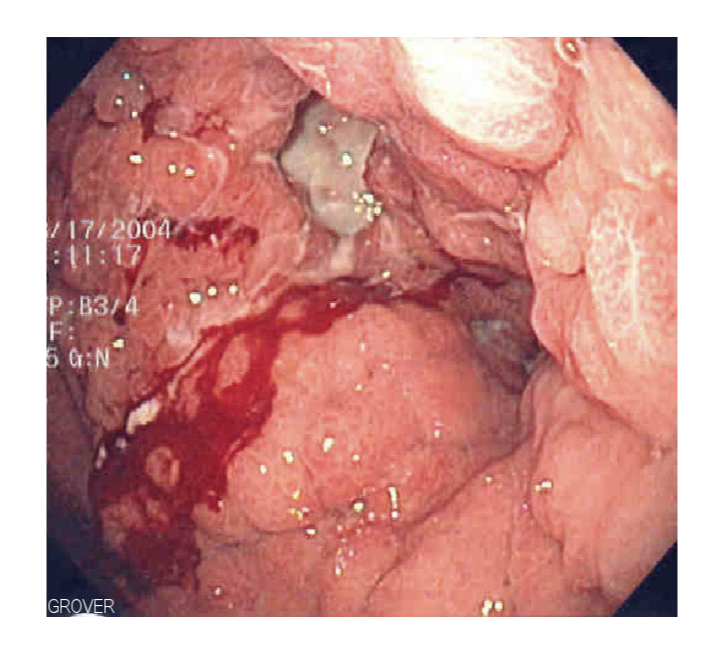

Linitis Plastica seen at endoscopy

More recently, the World Health Organisation (WHO) classified gastric cancers based on defined histological subtypes, which include:

- Papillary, tubular and mucinous adenocarcinoma: these correlate with the intestinal type based on the Lauren criteria

- Signet-ring cell and other poorly cohesive carcinomas: these correlate with the diffuse type based on the Lauren criteria

Early versus advanced

Classifying gastric cancers based on whether they are ‘early’ or ‘advanced’ refers to the extent of spread through the stomach wall, which includes the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa and serosa.

- Early: cancer confined to the mucosa or submucosa. May or may not be associated with lymph node involvement. Much better prognosis (>90% five-year survival). Further divided based on Paris classification of superficial GI lesions.

- Advanced: cancer invades the muscularis and beyond. Much worse prognosis with five year survival ≤60%. May be associated with lymph node and distant metastasis. Described using Borrmann’s classification into four subtypes.

Type IV advanced gastric cancer based on Borrmann’s classification is similar to diffuse gastric cancer with a linitis plastica appearance.

Molecular

Modern molecular techniques have allowed sequencing of gastric cancers and better understanding of the genetic mutations associated with different tumour types.

Gastric cancers are highly heterogeneous with numerous somatic mutations (i.e. occurring in the tumour) that differ significantly between individuals. TP53, also known as the 'guardian of the genome’ because of its crucial role in the cell cycle is the most commonly identified mutation.

Identifying molecular abnormalities has different clinical implications:

- Guide treatment: identification of HER2 positive tumours may be treated with trastuzumab (blocks the HER2 receptor).

- Determine prognosis: certain mutations are associated with more unstable tumours and worse prognosis.

- Suggest hereditary aggregation: mutations in CDH1 are linked to hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (see below).

Aetiology

The gram negative bacterium Helicobacter pylori has a significant role in the aetiology of gastric cancer.

Gastric cancer is a very heterogeneous condition, which is influenced by a variety of environmental, infectious, and patient-related factors (e.g. genetics).

Environmental

Smoking and diet are important environmental risk factors for gastric cancer formation

- Smoking: increase risk of gastritis, peptic ulcers and malignancy

- High salt intake: risk combined with presence of H. pylori infection. Thought to directly damage mucosa.

- Inadequate intake of fruit and vegetables

- Meat consumption: only possible link

Infectious

Helicobacter pylori is a gram negative spiral bacterium, which colonises the stomach. It has been implicated in up to 89% of non-cardia gastric cancers.

H. pylori infection usually begins in childhood, although the precise mechanism for acquirement and transmission of the organism is not fully understood. It causes both acute and chronic inflammation that promotes abnormal cellular growth, genetic mutations, and dysplasia (discussed in pathophysiology).

One of the main proteins involved in its pathogenies is CagA, which is an oncogenic protein that can disrupt epithelial intercellular junctions, increase cell proliferation, reduce apoptosis, and promote formation of adenocarcinomas

Other infections linked to gastric cancer include Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).

Patient-related factors

Patient-related factors include genetic polymorphisms (i.e. unique mutations that increase risk of gastric cancer), pernicious anaemia (autoantibodies directed against parietal cells leading to vitamin B12 deficiency) and Menetrier's disease (rare condition associated with overgrowth of glandular mucous cells).

In addition, some genetic mutations can be inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern leading to a very high risk of gastric cancer including hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC).

Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer

HDGC is a diffuse type of gastric cancer most commonly due to an inherited mutation in CDH1.

HDGC is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. The lifetime risk of gastric cancer is 70% in men and 56% in women. The median age at diagnosis is 38 years old.

The majority of cases are due to a pathogenic mutations in the CDH1 gene. This is needed for formation of cadherins, which are important in cell-to-cell interaction. Other genetic mutations have been linked to HDGC.

Patients with known HDGC are usually recommend prophylactic total gastrectomy due to the high risk of cancer. In addition, there is an increased risk of lobular breast cancer.

Pathophysiology

Gastric cancer is a heterogeneous condition associated with numerous genetic alterations.

The development of any cancer is based on the acquirement of sequential mutations that allow a cell to proliferate uncontrollably. By itself, uncontrolled proliferation is not sufficient for cancer development. Malignant cells must develop mechanisms to support their growth, resist cell death and invade normal tissue. These adaptations occur over years and some cancers have very classic sequences of events.

Correa’s cascade

The Correa cascade describes the classic sequence of histological lesions for the most common gastric cancer: intestinal type adenocarcinoma. It was first described in 1975, but later linked with infection by H. pylori following its identification as a cause of gastritis in 1983.

The sequence progresses from normal gastric mucosa to gastric dysplasia, which is high-risk of developing invasive carcinoma:

- Normal gastric mucosa

- Chronic non-atrophic gastritis

- Chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG)

- Intestinal metaplasia

- Dysplasia

Anatomical location

Distal gastric cancers (i.e. antrum or pylorus) are more commonly seen in countries with high incidence. Distal cancers are more likely to be intestinal type and associated with H. pylori infection. Proximal gastric cancers (i.e. cardia) are more likely in low incidence countries and unrelated to H. pylori infection.

Clinical features

Patients with gastric cancer may be asymptomatic or present with non-specific symptoms.

Symptoms

- Constitutional symptoms: fevers, anorexia, lethargy, weight loss

- Dysphagia: if involvement of gastric cardia

- Indigestion

- Dyspepsia

- Nausea/vomiting

- Haematemesis/melaena

- Post-prandial fullness

Signs

Usually absent unless late presentation with distant spread

- Pallor

- Cachexia

- Lymphadenopathy

- Virchow node: left supraclavicular node

- Metastatic lesions

- Hepatomegaly

- Sister Mary Joseph nodule: periumbilical metastasis

Paraneoplastic syndromes

These refer to the non-metastatic manifestations of malignancy.

- Acanthosis nigricans: velvety hyperpigmentation of the skin, usually in skin folds (e.g. axilla)

- Dermatomyositis: inflammatory myopathy characterised by a helicotropic rash (purple rash around the eyes) and Gottron's papules (red areas over the knuckles).

- Erythema gyratum repens: erythematous rash with an annular (ring-shaped) appearance. Usually involves limbs and trunk.

Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO)

GOO occurs when there is obstruction to emptying of the stomach at the pylorus. This may occur due to a fibrotic stricture of obstructing tumour.

Classic features include early satiety, abdominal fullness, nausea, vomiting, weight loss. On auscultation of the stomach there may be a succussion splash (sloshing sound heard on patient movement due to a full stomach).

Suspected cancer referral

Early recognition and diagnosis is essential to improve mortality.

The NICE (NG12) guideline outlines recommendations for the referral of suspected cancer cases including upper gastrointestinal cancers. Below details the recommended referral for suspected gastric cancer.

Urgent (two week wait) referral

This means referring a patient for appropriate investigations (e.g. gastroscopy) for suspected gastric cancer within two weeks. It is usually combined with a clinic appointment and CT imaging.

- Upper abdominal mass consistent with gastric cancer, OR

- Dysphagia, OR

- > 55 years with weight loss and one of the following:

- Upper abdominal pain

- Reflux

- Dyspepsia

Non-urgent referral

This means referral for a non-urgent gastroscopy to assess for gastric pathology. Usually performed within 6 weeks.

- Haematemesis, OR

- > 55 years with treatment resistant dyspepsia, OR

- > 55 years with upper abdominal pain and anaemia, OR

- Thrombocytosis with one of the following:

- Nausea/vomiting

- Weight loss

- Reflux

- Dyspepsia

- Upper abdominal pain

- Nausea/vomiting with one of the following:

- Weight loss

- Reflux

- Dyspepsia

- Upper abdominal pain

NOTE: Upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) investigations should also be considered to investigate for GI malignancy (inc. gastric cancer) in all postmenopausal female and male patients where IDA has been confirmed unless there is a history of significant overt non-GI blood loss. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines 2011.

Diagnosis

Gastric cancer is diagnosed using upper GI endoscopy and biopsies of suspected lesions.

Gastric cancer may be suspected based on clinical features or incidental finding on imaging (i.e. thickening of the gastric mucosa). However, definitive diagnosis is made using upper GI endoscopy, known as gastroscopy.

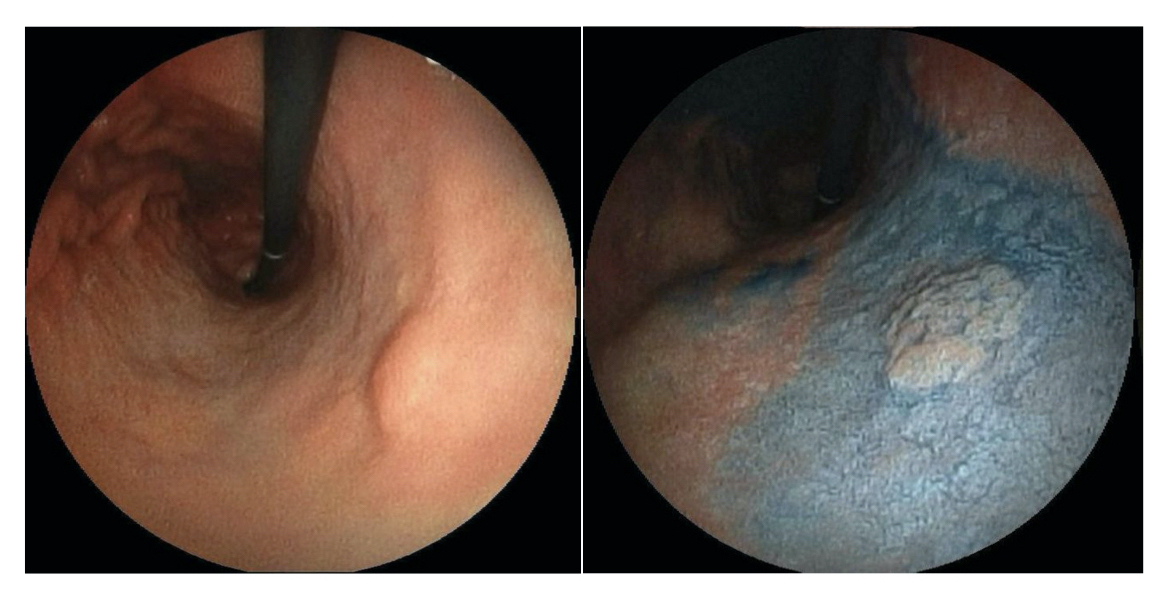

Evidence of early gastric cancer at gastroscopy

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

All patients with suspected gastric cancer should undergo gastroscopy to enable direct visualisation of the gastric mucosa followed by biopsies of suspected lesions. Biopsies are subsequently sent for histological analysis to see if any features of malignancy are present.

Investigations

Further investigations allow assessment of distant spread and key-organ function to help guide management.

Bloods

- Full blood count

- Serum iron, transferrin saturation, total iron binding capacity (TIBC)

- Urea & electrolytes

- Liver function tests

- Bone profile

- Clotting screen

- Renal function

Imaging

- CT chest/abdomen/pelvis: patients with suspected gastric cancer undergo CT imaging to help stage the cancer, which means assessing how locally advanced it is and looking for distant spread.

- Abdominal ultrasound: may be used to assess for liver metastasis. Usually superseded by CT.

- PET-CT: offered to patients with potentially resectable disease (i.e. candidates for surgery) to assess for distant disease not detected by conventional CT.

Special

- Gastroscopy: principle investigation for diagnosis

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS): performed at time of endoscopy. Sometimes completed to help more accurately stage gastric cancer if it will change management

- Diagnostic laparoscopy: can be offered to more accurately stage gastric cancer. Particularly important if the disease is locally advanced but potentially resectable.

HER2 testing

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) testing should be completed on patients with metastatic gastric cancer as treatment directed against the HER2 receptor may be used in treatment regimens.

Staging

The stage of a cancer describes the extent of cancer spread.

The stage of a cancer is critical to determine treatments, but can be very complex and important mainly for clinicians involved in treating patients with cancer. Stage also provides prognostic information.

Cancer stage is based on tumour size, presence of lymph node involvement and distant spread. We call these three factors ‘TNM’ (tumour, nodes, metastasis).

Tumour

- TX: Primary tumour cannot be assessed

- T0: No evidence of primary tumour

- Tis: Carcinoma in situ: intraepithelial tumour without invasion of the lamina propria

- T1: Tumour invades lamina propria or submucosa

- T1a: Tumour invades the lamina propria or the muscularis mucosae

- T1b: Tumour invades the submucosa

- T2: Tumour invades the muscularis propria

- T3: Tumour penetrates the subserosal connective tissue without invasion of the visceral peritoneum or adjacent structures

- T4: Tumour invades the serosa or adjacent structures

- T4a: Tumour invades the serosa

- T4b: Tumour invades adjacent structures

Node

- NX: Regional lymph node(s) cannot be assessed

- N0: No regional lymph node metastasis

- N1: Metastasis in 1–2 regional lymph nodes

- N2: Metastasis in 3–6 regional lymph nodes

- N3: Metastasis in 7 or more regional lymph nodes

Metastasis

- MX: Distant metastasis cannot be assessed

- M0: No distant metastasis

- M1: Distant metastasis or positive peritoneal cytology

Management

The management of gastric cancer depends on the extent of cancer and patients fitness.

Treatment options

There are numerous treatment options for the management of gastric cancer:

- Surgery: resection of gastric or gastro-oesophageal tumours (e.g. gastrectomy).

- Endoscopic techniques: mucosal resection or mucosal dissection

- Radiotherapy: use of high energy rays to destroy cancer cells.

- Chemotherapy: use of anti-cancer medications to destroy cancer cells

- Targeted cancer drugs: monoclonal antibodies against certain receptors (e.g. HER2)

- Palliative care: use of chemotherapy or radiotherapy for disease or symptom control without aiming to cure

- Best supportive care: focus primarily on symptoms and quality of life without systemic treatments.

Determining choice

Surgical resection of gastric cancer is potentially curable. However, patients with locally advanced disease are high risk of recurrence so a combination of therapies is needed.

- Operable (early stage): refers to patients with T1 tumours without lymph node involvement or metastasis. Endoscopic or limited surgical resection may be suitable

- Operable (advanced stage): refers to patients with >T1N0 tumours. All patients with stage IB-III gastric cancer may be considered for resection if fit enough. This needs to be combined with chemotherapy or chemoradiotherpy.

- Non-operable: refers to patients who are not suitable for operative management or there is evidence of distant spread. Chemotherapy is the main option. A small proportion may be considered for surgery if significant response.

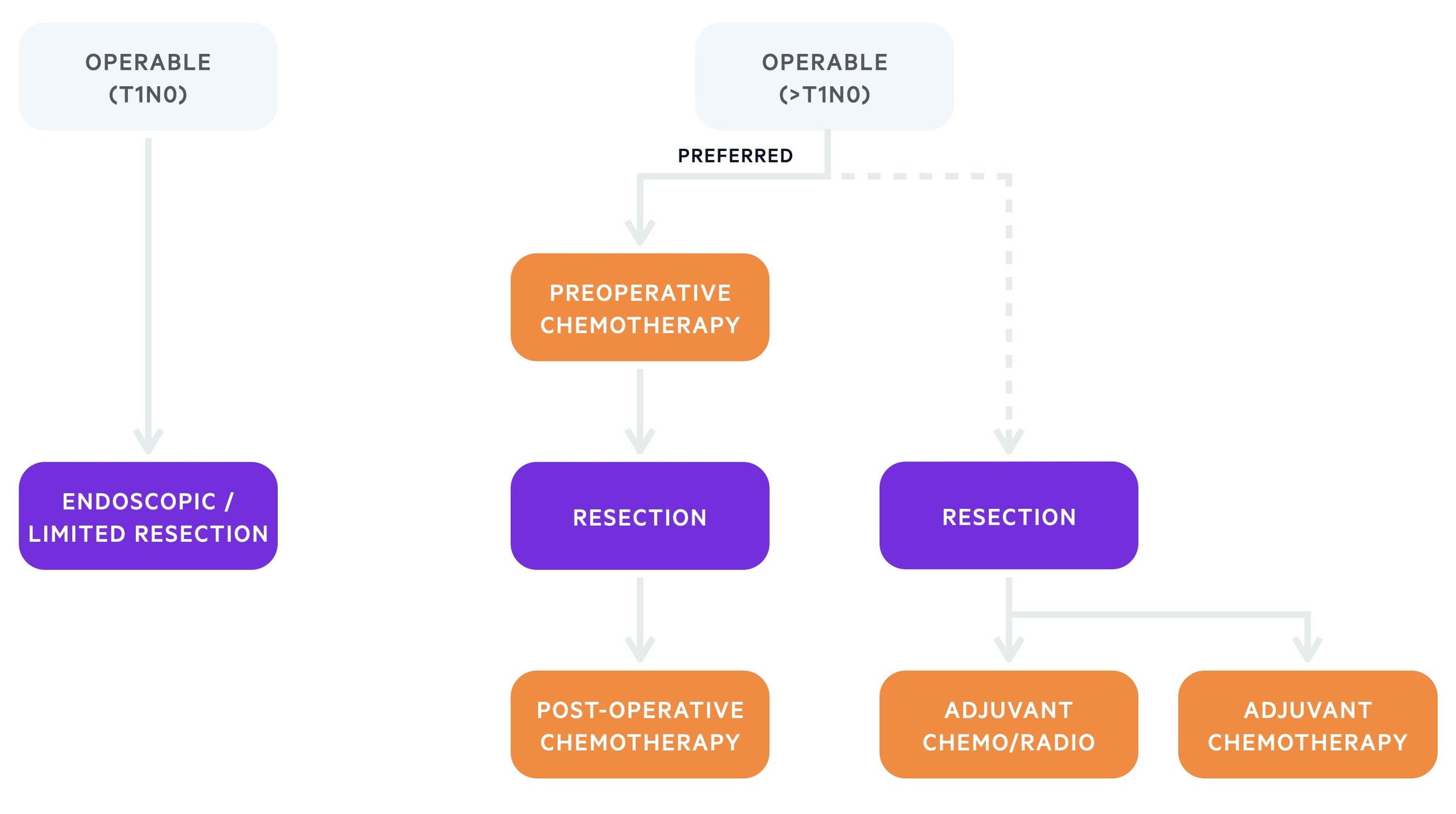

Operable

The treatment of choice for early disease is surgical or endoscopic resection.

Operative management is generally considered for patients who are surgical candidates without evidence of distant spread. Patients with early stage disease (T1N0) do not require combined management with chemotherapy. However, those with disease >T1N0 require a combination of treatment options (e.g. surgery and chemotherapy) due to the risk of recurrence.

Treatment algorithm based on the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) for gastric cancer (operable)

Surgery

Surgical resection involves removal of the whole stomach or only a portion of the stomach. The remnant stomach or oesophagus is then joined to the jejunum. Options include:

- Subtotal gastrectomy

- Total gastrectomy

- Oesophago-gastrectomy (if GOJ involvement)

The choice of surgery depends on the location and size of the tumour and presence of lymph node involvement. Patients with lymph node involvement will usually undergo lymph node dissection at the time of surgery.

Endoscopic therapy

Patients with small, early gastric cancers that are confined to the mucosa may be considered for endoscopic resection. There are two options:

- Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)

- Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD): treatment of choice

Systemic anti-cancer therapy

The principle anti-cancer therapy in gastric cancer is chemotherapy. Pre-operative chemotherapy, which includes a combination of platinum/fluoropyrimidine should be offered to all patients with ≥stage IB resectable gastric cancer.

If patients undergo surgery before administration of chemotherapy, it should be offered post-operatively and may be combined with radiotherapy.

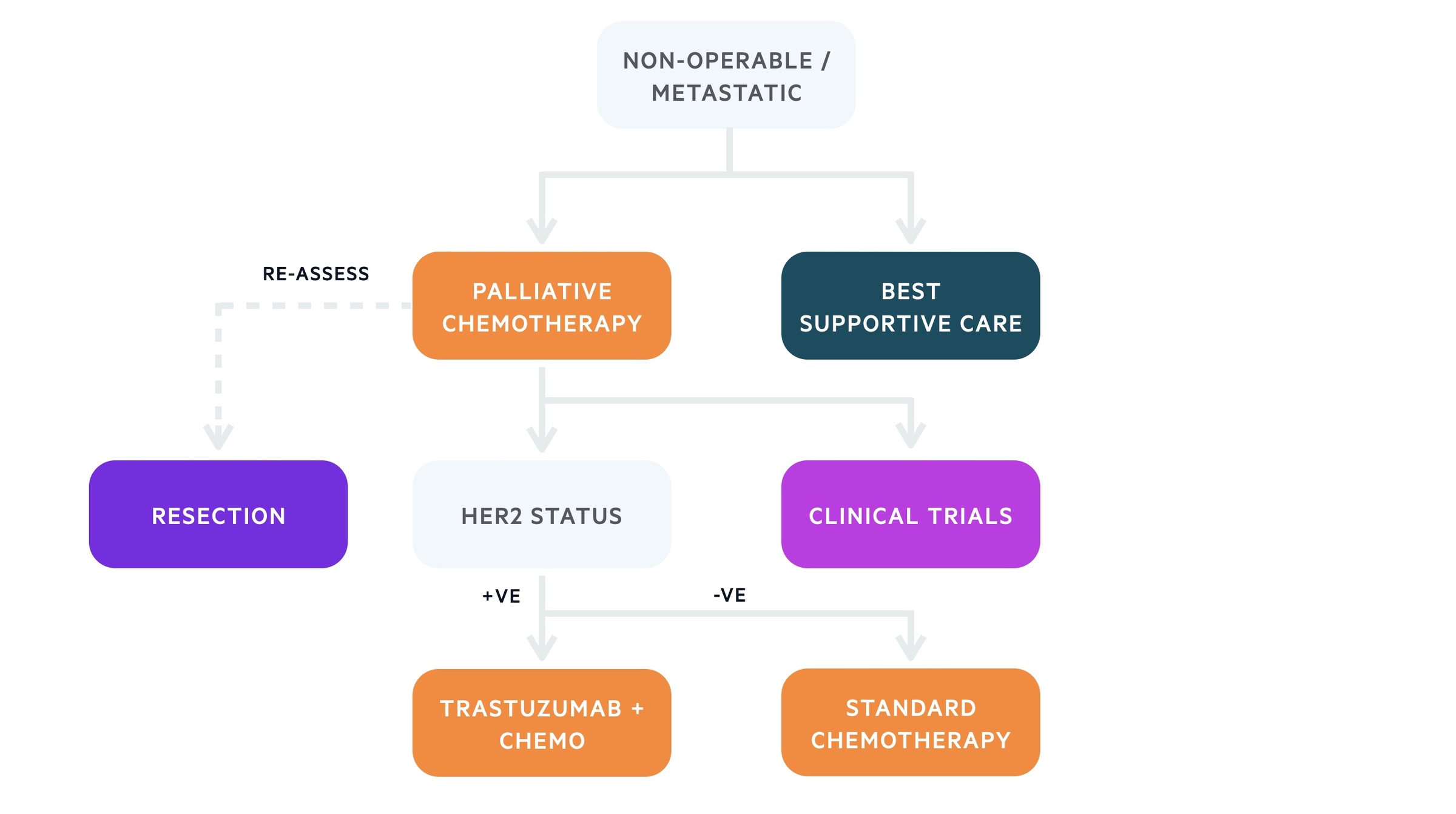

Non-operable

Patients with advanced non-operable or metastatic gastric cancer should be offered chemotherapy if fit enough.

The principle treatment for metastatic or non-operable gastric cancer is chemotherapy. This is usually platinum/fluoropyrimidine combinations. Those who are not fit enough to undergo systemic treatment should undergo best supportive care, which focuses on symptom control and quality of life.

Treatment algorithm based on the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) for gastric cancer (non-operable)

Systemic anti-cancer therapy

Chemotherapy forms the principle treatment in patients with metastatic or non-operable gastric cancer, which improves quality of life and survival. Chemotherapy combination regimens depend on whether the tumour is HER2 positive.

- HER2-negative advanced/metastatic gastric cancer: double/triple chemotherapy regimens (e.g. oxaliplatin, 5-Fluorouracil +/- epirubicin)

- HER-2-positive advanced metastatic gastric cancer: Trastuzumab (monoclonal antibody against HER2-receptor) in combination with platinum/fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy.

Newer agents and clinical trials may be available to patients. This depends on patient co-morbidities, performance status and patient choice.

Performance status

This describes a patients' level of functioning in terms of their ability to care for themselves, what they can do as part of their daily activities and their physical ability.

Performance status can be measures using the World Health Organisation (WHO) / Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale.

- Grade 0: Fully active, able to carry out all normal activities.

- Grade 1: Restricted physical activity but ambulatory and able to carry out light sedentary work (e.g. office work).

- Grade 2: Ambulatory and capable of all self care but unable to carry out any work activities. Out of bed >50% of day.

- Grade 3: Capable of only limited self-care, confined to bed or chair > 50% of waking hours.

- Grade 4: Completely disabled. Cannot carry on any self-care. Totally confined to bed or chair.

- Grade 5: Death.

Additional treatments

Endoscopic therapy including insertion of pyloric stents or palliative surgical diversions (e.g. palliative gastro-jejunostomy) may be needed in patients with significant gastric outlet obstruction.

Prognosis

The five year survival of gastric cancer is poor at ~20%.

Survival from gastric cancer depends on stage. The five year survival for early stage disease is almost 90% but only 24% in patients with stage 3 disease. The overall survival is poor because the disease is usually advanced at presentation and is more common in elderly patients who are likely to have multiple co-morbidities.

Nevertheless, survival from gastric cancer has significantly improved within the UK over the last 40 years.

Last updated: May 2021

Have comments about these notes? Leave us feedback